Well-field system

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

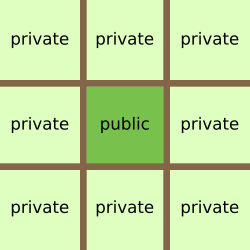

The well-field system (Chinese: 井田制度; pinyin: jǐngtián zhìdù) was a Chinese land redistribution method existing between the eleventh or tenth century BCE (Western Zhou dynasty) to around the Warring States period. Though Mencius describes examples from the Xia and Shang dynasties, these could be mythological or imagined, and credited King Wen of Zhou as one of the persons enacting the system.[1] The name comes from Chinese character 井 (jǐng), which means 'well' and looks like the # symbol; this character represents the theoretical appearance of land division: a square area of land was divided into nine identically sized sections; the eight outer sections (私田; sītián) were privately cultivated by farmers, or nong in Chinese, one of the occupations of the four occupations system; and the center section (公田; gōngtián) was communally cultivated on behalf of the government, or in some cases, the landowning aristocrat or duke.[2][3][4]

While all fields were government- or aristocrat-owned, the private fields were managed exclusively by farmers and the produce was entirely the farmers'. It was only produce from the communal fields, worked on by all eight families, that went to the government for famine distribution or the aristocrats and which, in turn, could go to the king as tribute.

However, in Mencius it is said that all people in office got 50 mu (about half an acre).[5]

As part of a larger fengjian system, the well-field system became strained in the Spring and Autumn period[6] as kinship ties between aristocrats became meaningless.[7] When the system became economically untenable in the Warring States period, it was replaced by a system of private land ownership.[8] It was first suspended in the state of Qin by Shang Yang and other states soon followed suit, though King Hui of Wei and King Xuan of Qi did think about restoring it after Mencius talked to them. They ultimately did not. [9]

As part of the "turning the clock back" reformations by Wang Mang during the short-lived Xin dynasty, the system was restored temporarily[10] and renamed to the King's Fields (王田; wángtián). The practice was more-or-less ended by the Song dynasty, but scholars like Zhang Zai and Su Xun were enthusiastic about its restoration invoking Mencius's frequent praise of the system.[11]

It is mentioned in the book of rites and it is said most anciently that the farmers only had to work the government fields 3 days a year; though it is unknown whether this is true, it is also said that the most ancient had houses given away, and 3 days was all that was required. In addition, it was stated the market of the goods would not be taxed; only a small fee for a stall, and travelers weren't taxed. It is later said in other texts that taxes were put on the market goods when a merchant was looking from side to side and people thought he was plotting.[12][13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mencius (2004-10-28). Mencius. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190268-5.

- ^ Zhufu (1981:7)

- ^ Mencius (2004-10-28). Mencius. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190268-5.

- ^ "Well-field system | Qin Dynasty, Irrigation & Agriculture | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Note that this source only corroborates basic details of the paragraph it is used as a reference for.

- ^ Mencius (2004-10-28). Mencius. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190268-5.

- ^ Zhufu (1981:9)

- ^ Lewis (2006:142)

- ^ Zhufu (1981:9)

- ^ Mencius (2004-10-28). Mencius. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190268-5.

- ^ Zhufu (1981:12)

- ^ Bloom (1999:129–134)

- ^ Confucius (2016-08-29). Delphi Collected Works of Confucius - Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-78656-052-0.

- ^ Mencius (2004-10-28). Mencius. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190268-5.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bloom, I. (1999), "The evolution of Confucian tradition in antiquity", in De Bary, William Theodore; Chan, Wing-tsit; Lufrano, Richard John; et al. (eds.), Sources of Chinese Tradition, vol. 2, New York: Columbia University Press

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2006), The Construction of Space in Early China, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Zhufu, Fu (1981), "The economic history of China: Some special problems", Modern China, 7 (1): 3–30, doi:10.1177/009770048100700101, S2CID 220738994