Wagner Group rebellion

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Wagner Group rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wagner Group–MoD conflict during the Russian invasion of Ukraine | |||||||

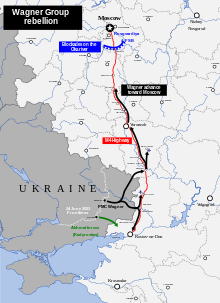

Map of the Wagner Group's advances into Rostov-on-Don and towards Moscow after emerging from Russian-occupied Ukraine | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,000–25,000[note 1] | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 killed[note 2] Several wounded[3] 5 vehicles destroyed[note 3] | 13–29 killed[5][6] 1–6 helicopter(s) shot down[note 4] 1 Il-22M airborne command-center plane shot down 2 vehicles captured[note 5] | ||||||

On 23 June 2023, the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company, engaged in a major uprising against the Government of Russia. It marked the climax of the Wagner Group–Ministry of Defense conflict, which had begun about six months earlier. Russian oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, who had been leading Wagner Group activities in Ukraine, stood down after reaching an agreement a day later.

Amidst the Russian invasion of Ukraine,[7] Prigozhin had come to publicly express his resentment towards Minister of Defence Sergei Shoigu and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov; he frequently blamed both men for Russia's military inadequacies, especially during the Wagner-led Battle of Bakhmut, and accused them of handing over "Russian territories" to the Ukrainians.[8] He portrayed the Wagner Group's rebellion as his response to the Russian Armed Forces allegedly attacking and killing hundreds of his Wagner mercenaries, which the Russian government denied. Characterizing it as a "march of justice" against the Russian military establishment, he demanded that Shoigu and Gerasimov be removed from their positions,[9] and eventually stated that Russia's justification for attacking Ukraine was a lie.[10] In the early morning of 24 June, President of Russia Vladimir Putin appeared in a televised address to denounce the Wagner Group's actions as treason before pledging to quell their uprising.[11]

Wagner mercenaries first seized Rostov-on-Don, where the Southern Military District is headquartered, while an armored column of theirs advanced through Voronezh Oblast and towards Moscow. Armed with mobile anti-aircraft systems, they repelled the Russian military's aerial attacks, which ultimately failed to deter the Wagner column's progress. Ground defenses were concentrated on the approach to Moscow, but before Wagner Group could reach them, President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko brokered a settlement with Prigozhin, who subsequently agreed to halt the rebellion. In the late evening of 24 June, Wagner troops abandoned their push to Moscow and those who remained in Rostov-on-Don began withdrawing.

In accordance with Lukashenko's agreement, Russia's Federal Security Service, which had initiated a case to prosecute the Wagner Group for armed rebellion against the Russian state under Article 279 of the Criminal Code, dropped all charges against Prigozhin and his Wagner fighters on 27 June. By the end of the hostilities, at least thirteen Russian soldiers had been killed and several Wagner mercenaries had been injured;[5] Prigozhin stated that two defectors from the Russian military had been killed on Wagner Group's side as well.[3] On 23 August 2023, exactly two months after the Wagner Group rebellion, Prigozhin was killed in a plane crash alongside other senior Wagner officials.[12]

Background

Yevgeny Prigozhin and the Wagner Group

In the early 1990s, Prigozhin, having served a decade in prison before embarking on an entrepreneurial career, emerged as a prominent figure in Saint Petersburg's business life, gaining recognition for a string of highly regarded restaurants. This connection facilitated a financial association with Putin, who was actively engaged in municipal politics during that period.[13][14] Prigozhin gradually evolved into a trusted and intimate confidant of Putin, forging a close personal bond.[15]

In 2014, Prigozhin founded the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company. Despite the legal prohibition of private military companies in Russia, Wagner operated unimpeded with implicit endorsement[15] and funding from the Russian government.[16][17] Many analysts have said the government employed Wagner services to allow for plausible deniability and obscure the actual toll in terms of casualties and financial costs of Russia's foreign interventions.[18]

Serving as a tool of Russian foreign and military policy, Wagner emerged as a formidable combat force in various regions, including the Donbas conflict.[19] It played a significant role during Russia's military intervention in the Syrian civil war, providing support to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad,[20][21] and has participated in conflicts in Mali, Libya, and the Central African Republic. Wagner has garnered infamy due to its ruthless methods and participation in war crimes throughout Africa, the Middle East, and Ukraine, perpetrating atrocities with impunity.[21][22][23]

The group maintains close ties with multiple African governments, enjoying considerable autonomy to exploit the natural resources of these nations in return for supporting local forces in their battle against anti-government rebels.[24][25] Wagner's economic endeavors in Africa witnessed an upward trajectory even amidst the Russian invasion of Ukraine,[24] as the funds generated were channeled towards financing the conflicts in Ukraine and other regions.[25]

Internal tensions during the invasion of Ukraine

Attempts to limit Prigozhin's influence

According to United States officials, Yevgeny Prigozhin had longstanding disputes with the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD) "for years" prior to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. However, these tensions escalated and became more public during this stage of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[26][27][28] During the initial stages of the invasion, the Russian Ground Forces suffered significant casualties, but the announcement of mobilization for reservists was delayed by Russian president Vladimir Putin. As a result, authorities actively sought to enlist mercenaries for the invasion, which led to a heightened influence and power for Prigozhin and the Wagner Group. Prigozhin was allocated substantial resources, including his own aviation assets. Additionally, starting in the summer of 2022, he gained the authority to recruit inmates from Russian prisons into the Wagner Group in exchange for their freedom.[29] Western intelligence estimated that the number of Wagner mercenaries increased from "several thousand" fighters around 2017–2018 to approximately 50,000 fighters by December 2022, with the majority comprising criminal convicts recruited from prisons.[29]

Although the government provided them with increasingly large resources, Wagner had no legal authority. Prigozhin held no official position and was neither appointed nor elected, meaning that he technically had no authority to answer to.[30] Furthermore, Prigozhin gained international recognition and abandoned his previously secluded personal life.[31] He frequently reported news from the front line while wearing military fatigues. Wagner began to be perceived as Prigozhin's private army, operating beyond the boundaries of Russian legislation and the country's military hierarchy. Dissatisfaction arose within the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and the General Staff, leading them to make efforts to curtail Prigozhin's growing influence.[30] In early February 2023, Prigozhin announced that Wagner had ceased recruiting prisoners,[32] which the British Defence Ministry interpreted as a government ban on such recruitment. This change was expected to diminish the group's fighting capacity.[33]

Conversely, Prigozhin portrayed himself as a populist figure who confronted the military establishment,[34] repeatedly accusing it of failing to protect national interests. On 1 October 2022, during Ukraine's Kharkiv counteroffensive, which expelled Russia from most of the region, Prigozhin criticized the Russian command, stating that "All these bastards ought to be sent to the front barefoot with just a submachine gun."[35] Due to his increased influence, Prigozhin was among the few who dared to complain about the military commanders to Putin.[36][37] Prigozhin primarily targeted the MoD, characterizing its officials as corrupt.[27][28] However, he also criticized other segments of the Russian elite,[38] including the members of Russian parliament and Russian oligarchs, whom he accused of attempting to "steal everything that belongs to the people" during the war.[39][38] In one of his statements, Prigozhin criticized Russian elite and their children for enjoying a luxurious and carefree life while ordinary people die in the war. Prigozhin drew parallels between this "division in society" and the one preceding the 1917 Russian Revolution, warning of potential uprisings by "soldiers and their loved ones" against such injustice.[40][41] The Institute for the Study of War noted that Prigozhin's statements increased his influence within the ultranationalist Russian milblogger community.[42]

Escalation during the battle of Bakhmut

During the grueling battle of Bakhmut, tensions between the Wagner Group and the MoD reached a critical juncture.[42] Prigozhin repeatedly voiced his dissatisfaction with the Kremlin's inadequate ammunition supply. He issued threats of withdrawing his forces unless his demands were fulfilled, specifically blaming Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov for the significant loss of life among Wagner fighters, which he claimed amounted to "tens of thousands" of casualties;[43] on another occasion he stated the number of casualties as 20,000.[44]

Following the Russian proclamation of victory in Bakhmut in late May 2023, Wagner began withdrawing from the city, giving way to regular troops.[45] Internal conflicts persisted between Wagner and the military during this transition.[46][47] Prigozhin claimed that the military made attempts to assault his retreating forces on both 3 June[48][49] and 5 June,[50][51] further claiming that the Russian military had laid mines on the route taken by Wagner during their retreat from Bakhmut.[52] On 5 June 2023, Prigozhin released a video through his social media platforms, purporting to depict the apprehended Lt. Colonel Roman Venevitin of Russia's 72nd Brigade, confessing to having ordered his troops to open fire on retreating Wagner forces, purportedly under the influence of alcohol.[50][51]

The culmination of the Bakhmut battle, where Wagner played a pivotal role, marked the onset of a period of increasing isolation from the establishment.[52] On 6 June 2023, Prigozhin made a public accusation, asserting that influential individuals were actively sabotaging his highly profitable catering enterprise in association with the Russian military. For more than ten years, these catering contracts had served as a source of his wealth and clout.[52] Concurrently, Prigozhin witnessed a surge in popularity, marking a notable shift in his public perception from non-political to political persona.[53][54]Order to integrate Wagner

In mid-June 2023, the MoD ordered Wagner to sign contracts with the military before 1 July. This move effectively integrated Wagner as a subordinate unit within the regular command structure, thereby diminishing the influence of Prigozhin. However, Prigozhin declined to sign the agreement, alleging incompetence on the part of Shoigu.[55][56] Reports from the independent Russian news outlet Meduza indicated that this development would undermine Prigozhin's hold over Wagner and jeopardize the group's profitable operations in Africa.[57] Prigozhin unsuccessfully attempted to circumvent the order for Wagner's subordination while intensifying his criticism of the MoD.[58] He went as far as advocating for the execution of Shoigu and hinting at a potential popular uprising against inept officials.[59] Prigozhin believed that Putin would ultimately side with him in his struggle against the MoD if he launched a mutiny.[59][60][61]

Planning the rebellion

U.S. intelligence agencies observed a gradual accumulation of Wagner forces near the Russian border[62] along with evidence of Wagner stockpiling equipment and resources in preparation for the rebellion.[63][64] Although they obtained information regarding the where and how of the planned rebellion, the exact timing remained unknown.[63] Western intelligence agencies reportedly uncovered the plan through communications intercepts and satellite image analysis.[64] Several weeks prior to the actual event, U.S. intelligence started foreseeing a significant Wagner insurrection[63] and obtained solid evidence of the imminent rebellion before 21 June.[65] Prigozhin seemed to have set the plan in motion following the MoD decision on 10 June, which would effectively integrate Wagner forces into the regular military.[63] The foreign intelligence findings indicate that the revolt was planned in advance, contradicting Prigozhin's claim that the decision to rebel was made on 23 June.[62]

Anonymous U.S. officials later disclosed[note 6] to The New York Times that Army General Sergey Surovikin had prior knowledge of the planned rebellion.[66] Surovikin had acted as an intermediary between Prigozhin and the military hierarchy[67] and was perceived to have close ties to Prigozhin.[66][67] CNN obtained documents that indicated Surovikin had a personal registration number with Wagner and held a covert VIP membership within the group, alongside at least 30 other high-ranking Russian military and intelligence officials.[68] Additionally, there were indications that other generals may have lent their support to the uprising. U.S. officials asserted that Prigozhin would not have instigated the rebellion unless he harbored the belief that he had backing from specific sectors within the Russian power structure.[66]

According to disclosures by Western officials to the The Wall Street Journal, the Russian Federal Security Service discovered the plan two days before it was scheduled to be executed. The discovery of the plan led to the premature start of the rebellion. Prigozhin intended to capture Defense Minister Shoigu and chief of general staff Gerasimov during their planned joint visit to the southern region of Russia that borders Ukraine and Western officials said the plan had a good chance of success had it not been discovered, leading Prigozhin to improvise an alternative plan. Western officials said intelligence findings indicated that Prigozhin's plan rested on his belief that a part of the armed forces would join the rebellion, and that they believed Prigozhin had informed some senior military offices about his plan.[64] Commander of the Russian National Guard Viktor Zolotov has claimed that Russian authorities learned about the planned rebellion and that it would be executed between 22 and 25 June.[64] According to anonymous accounts conveyed by Meduza, it's possible that the security services "didn't have the nerve to tell the president that something's up with Prigozhin [...] because if they reported the problem, decisions would have to be made. And how would you make that decision?" According to Meduza's sources, after Prigozhin failed to evade the order to integrate Wagner into the regular military, "Some bad foreboding spread in the air, that something was about to happen." Kremlin officials "talked about it in meetings, and came to the conclusion that [Prigozhin] is a daring opportunist who doesn't play by the rules. When it came to the risk of an armed insurrection, they thought it was nil." Consequently, they believed Prigozhin's announcement of an uprising to be a bluff intended to extract concessions, only realizing the seriousness of the situation once Wagner captured Rostov-on-Don.[58] Lukashenko has said that both he and Putin had "slept through this situation" and that both "thought it would fizzle out on its own [when it started to develop]".[69]

The Moscow Times reported that hours before his announcement of the rebellion, Prigozhin was secretly planning to attend a roundtable discussion in the State Duma opened by A Just Russia – For Truth leader Sergei Mironov in which MPs criticized the Kremlin's handling of the war effort in Ukraine. It added that Prigozhin was supposed to give a harsh criticism of the Russian military leadership from the Duma's chamber in a final attempt to win back Putin's approval. However, his plans were canceled at the last minute without explanation.[70]

Rebellion

Prigozhin's statements

Rebukes of the government and allegation of an attack on Wagner

In a video released on 23 June 2023, Prigozhin claimed that the government's justifications for invading Ukraine were based on falsehoods, and that the invasion was designed to further the interests of Russian elites.[71] He accused the MoD of attempting to deceive the public and the president by portraying Ukraine as an aggressive and hostile adversary which, in collaboration with NATO, was plotting an attack on Russian interests. Specifically, he denied that any Ukrainian escalation took place prior to 24 February 2022, which was one of the central points of Russian justification for the war.[72] Prigozhin alleged that Shoigu and the "oligarchic clan" had personal motives for initiating the war.[73] Furthermore, he asserted that the Russian military command intentionally concealed the true number of soldiers killed in Ukraine, with casualties reaching up to 1,000 on certain days.[74]

In an effort to create a pretext for rebellion,[75][76] later on 23 June, Prigozhin amplified a video that had already been circulating in Wagner-associated Telegram channels that reportedly showed the aftermath of a missile strike on a Wagner rear camp. Prigozhin accused the Russian MoD of conducting the strike, which he claimed killed 2,000 of his fighters.[77][78][79][80] The MoD denied the allegations of attacking Wagner's rear camps,[81] and the Institute for the Study of War was unable to confirm the veracity of the video, noting that it "may have been manufactured for informational purposes".[77]

Other observers have also questioned the veracity of the video: Meduza, in its 24 June investigation, claimed that the video of the missile attack on the Wagner camp was staged, citing the unusual behavior of the men filming and inconsistencies in the footage with what the aftermath of a large explosion would look like.[82] Georgy Aleksandrov, a war correspondent for Novaya Gazeta Europe, also thought that the video of the aftermath of the shelling did not look credible, noting "There are no obvious craters from the hits. No obvious body fragments. No general smoke. The fires don't look like remnants from rocket impacts."[83]

Call to rebellion

Prigozhin declared the start of an armed conflict against the Ministry of Defence in a message posted on his press service's Telegram channel. He called upon individuals interested in joining the conflict against the Ministry,[84] portraying the rebellion as a response to the alleged strike on his men.[85] Additionally, Prigozhin claimed that Shoigu had cowardly fled from Rostov-on-Don at nine o'clock in the evening.[84] Consequently, the Federal Security Service initiated legal proceedings against Prigozhin under Article 279 of the Criminal Code, which concerns armed rebellion.[86][87]

Many members of Wagner were not informed about the planned rebellion beforehand. As a result, they were perplexed by Prigozhin's call to arms and uncertain as to which faction they should align themselves with.[57] Demobilized Wagner veterans were instructed to remain on standby and await orders from Prigozhin. Individuals in Moscow without any affiliation with Wagner reported receiving calls, seemingly from the Wagner Group, urging them to join a rally in support of the rebellion. Similar calls were made to residents of Rostov-on-Don, soliciting support for the uprising.[57]

Surovikin and Lieutenant General Vladimir Alekseyev appealed to the Wagner mercenaries, urging them to cease hostilities.[88] Surovikin made his remarks in what the Financial Times described as a "hostage-style video" and had, as of 29 June, remained unaccounted for.[67] State-run Channel One Russia broadcast an "emergency newscast," during which host Ekaterina Andreeva declared that Prigozhin's statements regarding alleged attacks by regular military forces on Wagner positions were false. Andreeva also mentioned that Putin had been briefed on the ongoing situation.[89] In response to Prigozhin's statements, the country's military and National Guard deployed armored vehicles in both Moscow and Rostov-on-Don.[90] Rostov-on-Don is near the frontlines in Ukraine where Wagner troops had been operating, and is also where Prigozhin had claimed that Wagner troops were headed.[90] It is directly connected to Moscow by the M4 highway.[91]

Capture of Rostov-on-Don

During the early morning of 24 June, Wagner forces crossed into Russia's Rostov Oblast from Luhansk and swiftly captured Rostov-on-Don, encountering no apparent opposition. They successfully took control of the Southern Military District headquarters, establishing a secure perimeter in the adjacent streets.[92] Notably, Prigozhin, captured on film, was seen within the courtyard of the headquarters building.[93] The Wagner forces fortified their position by planting landmines and establishing security checkpoints in the city center of Rostov.[94] Wagner members sported silver armbands to distinguish themselves.[95][96]

Prigozhin held a meeting with Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-bek Yevkurov and Deputy Chief of Staff Vladimir Alekseyev at the headquarters, during which Yevkurov unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Prigozhin to withdraw his troops.[97] Prigozhin then hunkered down in a bunker in the city and took up command as a detachment of some thousands of Wagner forces advanced on Moscow.[64] Shooting and explosions were later heard. The Rostelecom building was fired at for unclear reasons.[92] Unconfirmed videos hinted at confrontations between Wagner forces and the military within the city.[98]

Many of Rostov's businesses and facilities remained closed. The municipal administration advised residents to stay at home (seemingly to little effect), but did not declare a counter-terrorism operations regime.[92] Local shops reduced their operating hours, and long queues formed at gas stations.[99] Some residents tried to stock up on essentials, while others sought to leave the city, resulting in traffic congestion and lengthy lines at the train station. However, there was no widespread panic among the populace. Certain residents congregated in the city center to meet Wagner fighters; the majority was supportive, although a few engaged in arguments with them. The Wagner mercenaries were pointedly amicable with the residents. Wagner forces subsequently urged civilians to stay off the streets for their own safety after which shooting and explosions broke out.[92]

Eyewitness footage depicted a long convoy of military and civilian vehicles heading towards the city, purportedly comprising Chechen paramilitaries (Kadyrovites) with the objective of engaging the Wagner forces.[100][101] According to Chechen state media and various accounts, they did not reach the city center and did not enter into any hostilities.[102][103] A commander of the Chechen forces later said that some of their teams had been as close as "500-700 meters from Wagner fighters".[104]

Advance towards Moscow

A convoy of Wagner forces headed to Moscow while Prigozhin commanded the rebellion from Rostov-on-Don.[64] The armored columns, consisting of a few thousand men with tanks, armored vehicles, anti-aircraft weaponry, and civilian trucks, began to advance rapidly towards Moscow in the early hours of 24 June.[105][106][107] While one column reportedly came from Rostov-on-Don, another crossed over from the occupied territory of Ukraine. The vehicles advanced across Voronezh Oblast where they encountered little resistance.[108][107] According to a source close to the leadership of the Donetsk People's Republic, the convoy bound for Moscow comprised approximately 5,000 combatants, reportedly under the leadership of the senior Wagner commander Dmitry Utkin.[109][110] Russian military bloggers claimed that the number of Moscow-bound troops stood at 4,000.[111] British intelligence reportedly estimated that some 8,000 Wagner mercenaries participated in the rebellion (including troops which did not move towards Moscow),[112] while Prigozhin claimed that the rebels were 25,000-strong.[2] The column did not attempt to occupy any cities it passed through, although it might have taken control of several air bases.[105]

Outside the regional capital of Voronezh, halfway between Rostov-on-Don and Moscow,[113] Wagner troops were attacked by a helicopter.[106][114][115] The Russian Air Force suffered significant losses while confronting Wagner troops, with at least one helicopter and an Il-22M airborne command-center plane shot down.[116][note 4] According to the British Ministry of Defence, the loss of the Il-22M was particularly significant, as it was one of only twelve aircraft of the type that had been key to the war effort against Ukraine, with Ukrainian forces unsuccessfully trying to shoot down such aircraft throughout the war.[117] At least thirteen Russian military personnel were killed.[5][118] Janes inferred the number to potentially be as high as 29, based on an estimation of the number of personnel needed to operate all of the reportedly destroyed equipment.[6]

Wagner fighters drove past Voronezh and continued to push through Voronezh Oblast throughout the early afternoon without entering important cities.[107] Social media posts also showed footage of fighting between Wagner troops and the military in Voronezh proper, with Reuters citing military reports.[113][119][120] Two missiles—likely fired by Wagner's air defense systems—struck an oil depot and a courtyard of a housing complex in Voronezh.[105] According to media reports, Wagner took control of all military facilities in the city.[121][122][106]

Wagner proceeded into Lipetsk Oblast, approximately 400 kilometres (250 mi) from Moscow.[123][124] They passed through the town of Yelets,[107] and continued north along the M4 highway.[125][126] In Lipetsk Oblast, authorities deliberately demolished highways using excavators in an effort to impede the convoy's progress.[100][127] Some roadways were blocked with trucks and school buses.[127][125] The military set up defensive lines along the Oka river (which flows just south of Moscow) and barricaded bridge crossings.[100][127] The governors of Lipetsk Oblast and Voronezh Oblast urged all civilians to stay indoors, following reports of military columns and clashes along the M4 highway.[128][129][130]

Prigozhin subsequently claimed that two Russian military defectors were killed while fighting alongside Wagner.[3] The Dutch OSINT website Oryx recorded five destroyed vehicles on the rebels' side, and two captured vehicles on the side of the government forces.[4]

There are reports that the closest to Moscow that Wagner troops got was the town of Kashira in southern Moscow Oblast, 95 kilometres (59 mi) south of Moscow.[125][131] Wagner presence is not visually confirmed any closer than Krasnoye in northern Lipetsk Oblast, 330 kilometres (210 mi) south of Moscow.[125]

Security measures

Sergei Sobyanin, the mayor of Moscow, declared the implementation of the counter-terrorism operations regime in the capital.[132] Armoured vehicles and an increased presence of security forces was observed throughout Moscow. Municipal authorities contemplated a curfew,[100] and billboards advertising Wagner recruitment were seen being hastily dismantled.[133] Der Spiegel reported a complete sell-out of all flights departing from Moscow as people sought to escape the impending situation.[134] According to the airplane-tracking website Flightradar24, an aircraft used by Putin took off from Moscow and headed towards St. Petersburg. However, according to Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, Putin was not on board,[135] and he remained in the Kremlin.[136] Authorities also announced travel restrictions in Kaluga Oblast, which is adjacent to Moscow, with Governor Vladislav Shapsha telling residents to "refrain from travelling by private vehicle on these roads unless absolutely necessary".[137]

Meanwhile, the Federal Security Service (FSB) raided Wagner headquarters in Saint Petersburg. Unconfirmed reports in Russian media said cardboard boxes containing 4 billion rubles ($47 million) were discovered from vehicles near the office,[138] and that cash in U.S. dollars, handguns,[139] gold bars and packs of an unknown white powder were also seized.[140][139] Prigozhin said that the money was intended for employee salaries, compensations to relatives of fallen Wagner mercenaries[140] and other company expenses.[138] He hinted at Wagner's covert global influence operations, including activities in Africa and the United States, which necessitated the use of cash.[140] The offices of a key Prigozhin media holding were also raided, with investigators seizing computers and documents.[141] Olga Romanova, a journalist and leader of the Russian civil rights organization Russia Behind Bars, accused the FSB of threatening relatives of convicts recruited by Wagner since the early hours of 24 June.[142] According to The Daily Telegraphs anonymous sources, U.K. intelligence similarly found that Russian intelligence agencies threatened to harm families of Wagner leaders during its advance on Moscow.[143][144]

On 4 July 10 billion RUB in cash found in Wagner offices was officially returned to Prigozhin, but no information was released on the whereabouts of the seized gold and white powder.[145]

On 22 December, The Wall Street Journal, citing sources from Western and Russian intelligence agencies, alleged that Nikolai Patrushev, Secretary of the Security Council of Russia, had also requested military assistance from Kazakhstan in the event of the Russian military failing to put down the rebellion, but was refused by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.[146]

Events in Syria

In Syria, where Wagner forces were part of the Russian military presence in the country's civil war, sources told Reuters that local authorities and Russian military commanders launched a swift crackdown on the Wagner Group to prevent the spread of the rebellion there.[147]

In the first hours of the revolt, about a dozen Wagner officers deployed in Homs Governorate and other areas were summoned to the Russian military base at Hmeimim, in the west of the country, according to Syrian military sources. Syrian military intelligence then cut communications overnight on 23 June from areas where Wagner forces operated to prevent them from communicating among themselves and with contacts in Russia. Wagner fighters were then asked to sign contracts putting them under the control of the Russian Defence Ministry and agreeing to a pay cut, with those refusing being removed from Syria aboard Russian Ilyushin aircraft. Those who refused were said to be "in the dozens".[147]

Resolution

Prigozhin allegedly made personal efforts to establish contact with the presidential administration on the afternoon of 24 June, including reaching out to Putin himself, who refused to speak with him. Final negotiations were reportedly conducted by Anton Vaino, the chief of staff, Nikolai Patrushev, the secretary of the Security Council, and Boris Gryzlov, the Russian ambassador to Belarus. Prigozhin strongly insisted that high-ranking officials participate in the negotiations, with Putin's refusal to engage paving the way for Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko's intervention.[148] Lukashenko reportedly spoke with Prigozhin upon Putin's request,[149] acting as a mediator to broker a settlement. They reached an agreement, which entailed the Wagner fighters ceasing their advancement and returning to their base, in exchange for a guarantee of their safety.[106] Lukashenko later recalled:

I said, 'Zhenya [the diminutive for Yevgeniy], no one will give you either Shoigu or Gerasimov, especially in this situation, you know Putin as well as I do. Secondly, he will not only not meet with you. He will not talk to you on the phone due to this situation'. Prigozhin was silent at first, but then burst out: 'But we want justice! They want to strangle us! We'll go to Moscow!'. I said, 'Halfway there you'll just be crushed like a bug'.

— Alexandr Lukashenko, speech during the presentation of general's epaulettes at the Palace of Independence in Minsk, Press Service of the President of the Republic of Belarus.[150]

In an audio statement, Prigozhin stated that he had accepted the deal to prevent bloodshed, and re-explained his motivations for the rebellion, emphasizing that it was not a coup attempt:[106][151][152][153]

They wanted to disband the Wagner military company. We embarked on a march of justice on June 23. In 24 hours, we got to within 200 kilometers of Moscow. In this time, we did not spill a single drop of our fighters' blood. Now the moment has come when blood could be spilled. Understanding responsibility [for the chance] that Russian blood will be spilled on one side, we are turning our columns around and going back to field camps as planned.

At around 11:00 p.m. (GMT+3) on 24 June, the Wagner Group commenced the withdrawal of their forces from Rostov-on-Don.[155][156] Residents of Rostov-on-Don cheered Wagner troops as they left the city, and some approached Prigozhin's vehicle and shook Prigozhin's hand through the window.[157] When asked to comment on the outcome of the revolt in the last known video of him during the rebellion, Prigozhin responded with levity: "It's normal, we have cheered everyone up".[62] On 25 June, Wagner forces started to withdraw from Voronezh.[158] Wagner forces reportedly returned to their positions in occupied regions of eastern Ukraine.[159]

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov announced that the charges against Prigozhin would be dropped and that Prigozhin would be sent to Belarus.[160] According to Peskov, Wagner fighters would not face prosecution, and those who did not participate in the rebellion would have the option to sign contracts with the Ministry of Defence. Peskov further conveyed that the Wagner organization as a whole would return to its previous wartime deployment locations. Putin's office reportedly expressed gratitude to Lukashenko for his efforts in quelling the rebellion.[161]

Reactions

Domestic

Vladimir Putin's address

Vladimir Putin addressed the nation on 24 June, denouncing Wagner's actions as "treason" and vowing to take "harsh steps" to suppress the rebellion. He stated the situation threatened the existence of Russia itself. Putin drew historical parallels to the Russian Revolution, which unfolded during the Russian Empire's engagement on the Eastern Front of World War I and resulted in territorial losses in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[74][136] Furthermore, Putin made an appeal to the Wagner forces who "by deceit or threats" had been "dragged" into participating in the rebellion.[162] After airing Putin's address, TV stations returned to their scheduled programming.[163]

In response, Prigozhin stated that his main goal was to remove Shoigu and Gerasimov from office[164] and reiterated his accusations of corruption against the MoD.[165]

Other government-aligned figures

Prominent Russian establishment politicians called on Prigozhin to stop his rebellion and expressed support for Putin.[166][167][168] Dmitry Medvedev, the leader of United Russia, the deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia, and a former president of the country, stated that "the world will be put on the brink of destruction" if Wagner would be able to take control of the government and gain access to nuclear weapons.[169]

Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic, called the mutiny "treason" and said his troops were en route to "zones of tension" to "preserve Russia's units and defend its statehood".[170] Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, the Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus', leader of the Russian Orthodox Church, called on Russians to pray for Putin.[171] Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of the Russian State Duma, expressed support for Vladimir Putin.[172] The leaders of Ukrainian regions occupied by Russia since 2014 also expressed support for Putin.[173][174]

Anti-war opposition and anti-government armed groups

Russian opposition groups responded in a variety of ways.[175] Exiled former oil magnate and opposition figure Mikhail Khodorkovsky urged Russians to support Prigozhin, saying that it was important to back "even the devil" if he decided to take on the Kremlin.[176] However, he later urged Russians to arm themselves, while stating that "Prigozhin is not our friend and not even our ally".[177] Jailed opposition leader Alexey Navalny criticized the event and Putin's handling of it writing "The fact that Putin's war could ruin and disintegrate Russia is no longer a dramatic exclamation." He also slammed how the government treated Prigozhin and Wagner in the aftermath in comparison to how himself and his Anti-Corruption Foundation were treated.[178]

The anarchist organizations Combat Organization of Anarcho-Communists (BOAK) and Autonomous Action both expressed in separate statements that Prigozhin and Putin were equally despicable, and that anarchists had no "side" to take in the conflict.[179] The BOAK urged fellow anarchists to "stay away", and let the warring factions "bleed each other as much as possible. That way, they won't be able to disturb people in the future." They also urged to "spend this time preparing for an armed conflict".[179] Russian Volunteer Corps leader Denis Kapustin praised Prigozhin, stating that despite their stark ideological differences, he considered Prigozhin "a patriot of Russia."[175] He later called for joining the rebellion.[180][181][182] The Freedom of Russia Legion compared the events to those during the Russian Revolution but advised readers to remember Wagner's numerous war crimes. They urged people not to "attribute military honor and valor to [Prigozhin] which does not exist."[175]

Ultranationalists and milbloggers

According to the Institute for the Study of War, Russian pro-war ultranationalists were divided between those who wanted to move past the rebellion and others who demanded solutions to the flaws in Russia's security exposed by the rebellion.[111] Igor "Strelkov" Girkin called for the execution of Prigozhin for the rebellion and his "murder" of Russian officers, demanding it as "necessary for the preservation of Russia as a state."[183]

Wider public

There were no sizeable spontaneous displays of public support for the Putin government during the rebellion.[184] The Russian population displayed a predominantly "silent" and apathetic reaction.[185][186] Russia analyst Anna Matveeva contrasted the Russian public's response to that of the Turkish public during the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, where numerous Turkish citizens actively participated in anti-coup demonstrations.[187] In Rostov-on-Don, which was occupied by Wagner forces, videos emerged of residents welcoming the rebels, bringing them amenities and cheering.[188][185]

A survey by Russian Field, a Moscow-based opinion poll company, released on 3 July, found that public support for Prigozhin fell by 26 percentage points in the days after his unsuccessful rebellion, but that 29% of survey respondents continued to view Prigozhin positively.[189][190] It is difficult to accurately capture public opinion in Russia; at least 70% of people whom Russian Fields contacted by telephone refused to respond to the poll.[189] The pollster's findings of a sharp drop in support for Prigozhin was consistent with the findings of a separate sentiment analysis study of Russian social media and internet comments.[189]

After explosions near Voronezh caused by Russian artillery fire, the previously existing Internet meme "to bomb Voronezh", which referred to self-destructive blunders by the Russian government, resurfaced on Russian social media.[191][192][127]

International

Western leaders mostly refrained from directly commenting on the rebellion as it unfolded and immediately after, primarily due to concerns that Putin would exploit such comments to claim that it was a foreign conspiracy.[193][194] Additionally, concerns were raised over control of the Russian nuclear arsenal.[195] U.S. President Joe Biden discussed the situation with French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.[196] Following the rebellion's conclusion, Biden said that Putin had "absolutely" been weakened by the mutiny.[197]

In a phone conversation with Putin on 24 June, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that Turkey was ready to assist in finding a "peaceful resolution"[198] and urged Putin to act sensibly.[199][200]

In Georgia, there were demands for the closure of its border with Russia, but the Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs stated that it was presently unnecessary.[201]

Ukrainian officials, including President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his advisor Mykhailo Podolyak, stated that "Russia's weakness is obvious" and that the insurrection was evidence of Russia's political instability, including infighting among elites.[202][203][204][205][206] Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba called the rebellion an opportunity for the international community to "abandon false neutrality" on Russia and to provide the Ukrainian government with all the weapons it needs to push Russian forces out of Ukraine.[207]

Moldovan foreign minister Nicu Popescu said that the events in Russia were proof that Moldova should continue on its trajectory of distancing itself from the "Eurasian space of destruction and war" and towards the European Union to ensure peace, stability and democracy in the country.[208]

Commenting on the negotiations, Belarusian President Lukashenko claimed to have convinced Putin to engage in dialogue with Prigozhin rather than assassinating him "because afterwards there will be no negotiations and these guys will be ready to do anything".[184] Lukashenko also claimed that Belarus' national defense will benefit from Wagner's expertise.[209] Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya stated on Twitter that the rebellion exposed the "weakness" of Putin and other dictatorial regimes,[210] and stated that "We must seize this moment now."[211] Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment commander Dzianis Prokharaŭ expressed a similar sentiment in a video address on social media, calling on Belarusian military personnel not to interfere in the events.[212][213] Valery Sakhashchyk, the Representative for Defense and National Security in the Belarusian United Transitional Cabinet in exile, called for a quick decision to either "use [the] historical chance and become a prosperous European country" or "lose everything". He called for the Belarusian military to assert the Nation's independence from Russia, to "unite the nation", and to "tune in to our wave and stay in touch".[214][215]

A Belarusian foreign ministry official described the rebellion as a "gift to the collective West".[216]

North Korea[217][218] and China expressed support for Putin.[219][220] President Milorad Dodik of Republika Srpska and former member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, voiced support for Putin.[221] Muhoozi Kainerugaba, son of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and commander of the Special Forces Command, stated that Uganda could send soldiers to Russia to help Putin quell the rebellion if necessary.[citation needed]

Aftermath

Fallout and restoring order

A sense of normalcy swiftly returned to Moscow. On 25 June, workers initiated the repairs of roads that had been destroyed to impede Wagner's advancement.[222] The "counter-terrorism operations regime" was lifted in Moscow on 26 June.[223] Following the uprising, the value of the Russian ruble sharply declined, reaching its lowest exchange rate since March 2022.[223] On 26 June, the MoD made an official announcement stating that Shoigu had paid a visit to the troops stationed in Ukraine.[224] Shoigu was prominently featured in state media coverage, often appearing alongside Putin, in the following days, in an apparent show of confidence.[225] Moreover, Putin undertook a series of public meet-and-greets, a departure from his typically secretive nature, seemingly aiming to showcase public backing.[226] On 10 July, the Defence Ministry released video footage purportedly showing Gerasimov listening to a report about Ukrainian missile attacks, his first public appearance since the revolt.[227]

Subsequent statements

On 26 June, Prigozhin released a recorded statement in which he defended the insurrection. He claimed that the objective was to save the Wagner Group and hold accountable inept government officials. Prigozhin emphasized that the uprising aimed not to overthrow the government and reiterated his accusation that the shelling of Wagner troops by the regular military sparked the rebellion. Prigozhin also favorably compared Wagner's ability to credibly threaten to capture Moscow with the military's failed attempt to capture Kyiv.[228]

Hours after Prigozhin's audio message, Putin addressed the nation once again. He rebuked the unnamed individuals who led the rebellion and reiterated his belief that it constituted an act of betrayal. However, Putin characterized Wagner commanders and fighters as predominantly patriots who were "covertly used against their comrades-in-arms." He confirmed that Russian servicemen were killed by Wagner, referring to them as heroes. Putin also stated that members of the group who do not wish to become regular contractors were allowed to transfer to Belarus.[229][230]

On 3 July, Shoigu made his first public statements since the rebellion, praising the loyalty of the armed forces and the continued adherence to operations of Russian forces in Ukraine.[231]

Fate of the Wagner Group and Yevgeny Prigozhin

Closure of criminal case and initial statements

On 27 June, Russian authorities said they had closed the criminal investigation and dropped the charges against Prigozhin or any other participants in the rebellion,[232] and that Wagner's heavy military equipment was to be transferred to the Russian armed forces.[233][234] The authorities stated that rebels had "stopped the actions directly aimed at committing a crime".[235] In Belarus, construction of camps for the Wagner Group was reported to have begun in Mogilev Region.[236] On the same day, Lukashenko confirmed the arrival of Prigozhin in Belarus, saying that he was welcome to stay "for some time".[237]

Also on 27 June, Putin said that the Wagner Group was "fully financed" by the Russian government.[238][239] This was the first admission by Putin of a link between Wagner and the Russian government, reversing years of Kremlin's denials of any connection.[238] Putin said that the Russian government paid more than 86 billion RUB (940 million USD) to Wagner from May 2022 to May 2023.[239] Although Putin claimed that Wagner was "fully" funded by the state, the group also obtains revenue from other sources, including Prigozhin's business dealings and payments from governments who hired Wagner (such as the Malian government, which reportedly had paid Wagner more than $10 million each month).[240] Putin's admission that Wagner was state-funded carries implications on the question of whether Russia is responsible, under the law of armed conflict, for atrocities committed by Wagner personnel in Central African Republic and elsewhere around the world.[240]

On 29 June, the BBC rang over a dozen recruitment centers using Russian phone numbers including in Volgograd, Krasnodar, Murmansk and Kaliningrad. The BBC was told that they were still signing contracts with the Wagner group and not the Russian MoD. A man in Volgograd said to the BBC: "It's absolutely nothing to do with the defence ministry... Nothing has stopped, we're still recruiting."[241]

In the week following the rebellion, Putin moved to take control of the network of business enterprises previously controlled by Prigozhin and Wagner, including hundreds of businesses in Russia and abroad.[242] Prigozhin's media empire was dismantled, and his propaganda operation was taken over by the government, with internet polemicists that had previously backed Prigozhin and attacked his enemies beginning to attack Prigozhin instead. Prigozhin's catering businesses began losing government contracts.[141] On 29 June, the milblogger Rybar, a former press officer for the MoD claimed that a purge was underway, targeting generals who demonstrated "a lack of decisiveness" when dealing with Wagner.[243]

Multiple publications reported that General Sergey Surovikin had been arrested by authorities after the rebellion.[244] However, on 12 July, the head of the defence committee of the State Duma, Andrey Kartapolov, said that he was "resting."[245] On 22 August, Surovikin was reportedly removed as commander of the Russian Aerospace Forces.[246] On 29 June, Surovikin's deputy, Colonel-General Andrei Yudin, was fired from the army.[247] On 5 July, General Yunus-bek Yevkurov was noted to have been absent from a military meeting.[248]

On 5 July, Sergei Mikhailov [ru], the general director of the state news agency TASS, was replaced by Andrey Kondrashov [ru], who was the press secretary for Putin's reelection campaign in 2018. The Institute for the Study of War said it was a possible indication of the Kremlin's unhappiness with media coverage of the rebellion.[249]

On 21 July, Igor Girkin, who commanded separatist fighters during the War in Donbas and was convicted in absentia by a Dutch court for the MH-17 shootdown in 2015, was detained by the FSB according to his wife Miroslava, on charges of extremism. He had been an open critic of Putin and his generals' handling of the war in Ukraine and called for his overthrow earlier in the week. The RBC newspaper reported that his arrest was possibly related to a petition from a member of the Wagner Group.[250]

On 5 July, the state television channel Russia-1 broadcast a program on Prigozhin and the Wagner Group, calling Prigozhin a traitor and adding that criminal cases against him over his rebellion were still ongoing.[251] It published footage of what was supposedly Prigozhin's opulent residence. Images purportedly showing of Prigozhin wearing wigs and various disguises also surfaced on the internet.[190]

According to a Guardian report published on 6 July based on sources with knowledge of Wagner's African operations, there had been no abnormal movements of Wagner personnel in Africa since the abortive rebellion.[252] However, on the same day as the Guardian report, the newspaper Jeune Afrique reported the departure of Wagner personnel in the Central African Republic, with more than 600 employees departing from Bangui M'Poko International Airport, citing NGOs and analysts. Video also emerged showing uniformed Wagner operatives reports gathering from a helipad.[253] The movements were later claimed by the office of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra on 8 July as a regular rotation.[254]

On 12 July, the Russian Ministry of Defence said that the Wagner Group had turned over more than 2,000 pieces of military hardware, which included tanks, mobile rocket launchers and anti-aircraft systems. The Ministry also said it received "more than 2,500 tons of various types of ammunition and about 20,000 small arms."[255]

On 13 July, the US Department of Defense assessed that the Wagner Group was no longer participating significantly in military operations in Ukraine.[256]

On 14 July, the Belarusian Defence Ministry said that the Wagner Group had begun training soldiers in the country and released a video showing Wagner fighters instructing Belarusian soldiers at a military range near Osipovichi, about 90 kilometers (56 miles) southeast of the capital Minsk.[257]

On 15 July, the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine confirmed the arrival of the Wagner Group in Belarus, with an unconfirmed report saying that a convoy of some 60 Wagner vehicles had entered the country.[258] It estimated that they had been deployed at least 100 kilometers from the Ukrainian border and put the number of mercenaries in the hundreds. Its spokesman said that they did not believe the deployment posed a serious threat to Ukraine but warned that Wagner could be used to destabilize the situation along the border.[259]

Prigozhin's return to Russia

On 27 June, Lukashenko confirmed the arrival of Prigozhin in Belarus saying that he was welcome to stay "for some time".[237] But on 6 July, Lukashenko said Prigozhin had returned to Russia and was in Saint Petersburg.[260][261][262]

The French newspaper Libération, citing Western intelligence sources, reported that Prigozhin had been back in Moscow since at least 1 July to negotiate the Wagner Group's fate with Putin, and that he met with Russian National Guard commander Viktor Zolotov and SVR head Sergey Naryshkin.[263] On 10 July, the Kremlin said that Putin met with Prigozhin and 35 other commanders of the Wagner Group on 29 June to discuss developments in Ukraine, with Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov saying that the president "gave an assessment of the company's actions on the front," as well as on the rebellion, while listening to the commanders' explanations and suggesting "variants of their future employment" and combat roles. Peskov also said that Prigozhin expressed Wagner's unconditional support for Putin.[264] In an interview published on 13 July by the newspaper Kommersant, Putin said he offered to retain Wagner as its own unit in the Russian military led by their current commander, who the newspaper identified only by his call sign of "Grey Hair", only for Prigozhin to reject the proposal. Putin also insisted that the Wagner Group could not exist in its current form, citing the law against private military organizations.[265]

On 19 July, Prigozhin made his first public appearance since the end of the rebellion. In a phone video showing him addressing his men, he said his forces would no longer fight in Ukraine and focus on training soldiers in Belarus and maintaining its activities in Africa instead.[266] Following that, in late July, he was present on the sidelines of the 2023 Russia–Africa Summit in Saint Petersburg.[267]

Death of Prigozhin and Utkin

On 23 August, Prigozhin and nine others including Wagner co-founder Dmitry Utkin were killed in a plane crash as his private jet traveled from Moscow to Saint Petersburg.[268] Russian state-owned media agency TASS reported that Prigozhin had been on the passenger list of the flight.[269] A Wagner-associated Telegram channel claimed the jet was shot down by Russian air defenses over Tver Oblast.[12] The passengers' deaths were officially confirmed on 27 August, following genetic analysis conducted on the remains recovered from the wreckage.[270]

Measures of NATO countries

In response to events, Estonia strengthened its border security,[271][203] while Latvia closed its border with Russia and suspended the entry of Russian citizens.[272] Concerned about the potential concentration of Wagner forces in neighboring Belarus, Latvia and Lithuania made a joint request to NATO for additional troops to be deployed to their countries, specifically along the eastern border of the alliance. Responding to earlier tentative plans to reinforce Lithuania, German Minister of Defense Boris Pistorius announced on 26 June that Germany, as the leading nation of the existing NATO battle group stationed in Lithuania, would dispatch a complete brigade consisting of 4,000 troops. This deployment aims to establish the necessary infrastructure for permanent stationing by 2026.[273][274][275] On 2 July, Poland announced it was sending 500 police and counterterrorist forces to reinforce its border with Belarus following the Wagner Group's redeployment there.[276] It later sent an additional 1,000 soldiers and equipment to the border.[277]

Analysis

Political

The rebellion, the first of its kind in Russia since the constitutional crisis of 1993,[127] was widely regarded in the following days as the most significant challenge to Putin's 23-year-long reign.[278][279][102] Multiple publications have noted that the rebellion has weakened Putin's public image.[280][281][282] Andrey Kolesnikov expressed a view that although the rebellion eroded Putin's image, the Russian population did not view Prigozhin's challenge to the establishment as a credible alternative. Therefore, they are assessed likely to continue providing support, whether genuine or feigned, to Putin's administration.[283] According to some analysts, the rebellion laid bare an inherent weakness of Putin's system of power built upon a ruling coalition of competing power centers[284][60][285] and a structure of subordinate "nominal" institutions[285] that was strained by the descent into a militarised state and society.[60] According to a New York Times analysis, the rebellion undermined Putin's legitimacy which relies on being viewed as a guarantor of stability and security, which may cause a lasting erosion of support among the Russian power elite.[286] According to Meduza, the rebellion did not last long enough to show whether Prigozhin's radical populist rhetoric enjoyed a genuine base of support among Russia's security services.[285]

Prigozhin's failed rebellion has been described as a desperate last-ditch effort in a losing power struggle against factions within the Russian establishment that he despised.[59] According to some commentators, the rebellion ended with relatively few immediate repercussions for the perpetrators that had been labelled as traitors by Putin, suggesting that Putin's rule was weak enough to challenge.[60]

The head of the Russian National Guard, Viktor Zolotov, was described as emerging victorious from the rebellion. Zolotov claimed credit and was praised by Putin for defending the capital Moscow against the Wagner Group. On 27 June, Putin declared that the Russian National Guard would be equipped with heavy weapons, including tanks, in order to suppress any potential future uprisings and assume a more prominent position in the Russo-Ukraine conflict.[287][67] According to Time magazine, Zolotov's increased authority may signify the initiation of a purge of Putin's opponents.[288]

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) said that Lukashenko was using his role in resolving the rebellion to gain influence and leverage in his relation with Russia, and that he may use the presence of Wagner to reduce the Belarusian military's dependence on Russia.[289]

Military

Western officials believed that Prigozhin would have faced a decisive defeat had he tried to capture Moscow and that this was likely the reason why Prigozhin ultimately agreed to a negotiated resolution.[63] According to Western intelligence analysis, had a negotiated solution not been reached, the rebellion would have likely culminated in a violent showdown in Moscow, resulting in the deaths of thousands.[64][290] Meanwhile, according to a Guardian analysis, "The emerging consensus – from experts and in western capitals – is [that the rebellion] was far less than an attempted coup, and more an impulsive demonstration that quickly got out of hand." According to The Guardian, air strikes on the column were conducted because no ground defense force was available to counter the convoy and with Moscow's defenses deficient, it was conceivable that the Wagner convoy would have penetrated the hastily erected defensive lines on the Oka River and reached the roadway circle surrounding Moscow and possibly have captured the capital, however, this may have been a futile act as it was becoming increasingly clear that he failed to rally outside support which was essential for his rebellion to succeed.[291] The ISW assessed that Wagner staked its chances on quickly rallying sufficient support from parts of the regular military to make an armed conflict with forces loyal to the MoD feasible.[111]

According to a senior U.S. Department of Defense official, U.S. intelligence agencies monitored the defection of large numbers of Russian soldiers from their military commanders, who then joined the Wagner movement. The official further stated that the operations carried out by Wagner were widely supported by soldiers and officers deployed inside Ukraine as well as in Russian territory and bases near the Ukrainian border.[292] U.S. and allied officials and independent experts consulted by The New York Times said that Prigozhin appeared to believe that a significant part of the Russian military would take his side during the rebellion.[66]

The ISW commented that "the rebellion exposed the weakness of the Russian security forces and demonstrated Putin's inability to use his forces in a timely manner to repel an internal threat and further eroded his monopoly on force"; and that the Russian military's combat capabilities did not seem to be "substantially impacted" by the rebellion.[111] According to CNN, allies cautioned Ukraine to avoid taking advantage of the rebellion to conduct strikes inside Russian territory.[63] According to analysts consulted by The New York Times, the enduring systemic problems within the Russian military, which were strongly criticized by Prigozhin and widely condemned by the soldiers, were likely to persist following the rebellion. This, in turn, would exacerbate the decline in morale.[293]

See also

- Kornilov affair, an attempted coup against the Russian Provisional Government in 1917

- 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, an attempted coup by the State Committee on the State of Emergency against President Mikhail Gorbachev in August

- Timeline of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (8 June 2023 – 31 August 2023)

Notes

- ^ Lower estimate per The Daily Telegraph citing anonymous sources from U.K. security services,[1] upper estimate per Prigozhin[2]

- ^ Two Russian soldiers who had defected to Wagner Group were killed during the rebellion, per Prigozhin.[3]

- ^ Two UAZ-23632-148-64, one AMN-590951, one Kamaz 6x6 and one Ural-4320[4]

- ^ a b BBC Verify has confirmed the loss of one Mi-8 transport helicopter.[116] Other outlets have conveyed reports of Russian social media users and Ukrainian intelligence that six helicopters were shot down, with a varying degree of confirmation—namely: three Mi-8MTPR-1 electronic warfare helicopters, one Mi-35 Hind, one Ka-52 Alligator, and one Mi-8.[294][5][125]

- ^ 1 Tigr and 1 Kamaz-435029[4]

- ^ The New York Times noted that U.S. officials would have a vested interest in selectively disseminating information damaging to Surovikin whom they believe to be more effective than other members of the Russian military command.[66]

References

- ^ Riley-Smith, Ben; Freeman, Colin; Kilner, James (26 June 2023). "Russian agents' threat to family made Prigozhin call off Moscow advance". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

It has also been assessed that the mercenary force had only 8,000 fighters rather than the 25,000 claimed

- ^ a b Williams, Tom; Nancarrow, Dan (24 June 2023). "Live: Wagner fighters allegedly march into Russia, with leader vowing to go 'all the way' against military". ABC News. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

Wagner is meant to be 25,000 with another 25,000 in Russia.

- ^ a b c d Prigozhin, Yevgeny (26 June 2023). "'We did not want to spill Russian blood': Prigozhin makes statement on Wagner Group's mutiny attempt". Novaya Gazeta Europe. Novoya Gazeta Europe. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

Several PMC Wagner fighters were injured. Two were killed — they were Russian Defence Ministry soldiers who joined us voluntarily.

- ^ a b c "Chef's Special – Documenting Equipment Losses During The 2023 Wagner Group Mutiny". Oryxspioenkop. 24 June 2023. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "LIVE — Wagner chief 'humiliated' Putin, Ukraine says". Deutsche Welle. 25 June 2023. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

At least 13 Russian servicemen perished in the Wagner mercenary uprising, according to pro-Kremlin military bloggers. The number may have actually been more than 20, independent commentators reported on Sunday, citing the downing of six helicopters and a reconnaissance plane ...

- ^ a b Jennings, Gareth (26 June 2023). "Russian Air Force suffers significant losses in Wagner mutiny". Janes. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

If correct, these aircraft losses would amount to about 29 VKS crew members killed (two for the Ka-52, three for each Mi-8 and the Mi-35, and 12 for the Il-22).

- ^ John, Tara (24 June 2023). "Wagner chief to leave Russia for Belarus in deal that ends armed insurrection, Kremlin says". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Khaled, Fatma (23 June 2023). "Prigozhin Accuses Putin's Military Leaders of 'Genocide' Against Russians". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ O'Brien, Phillips (24 June 2023). "Prigozhin Planned This". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (23 June 2023). "Wagner chief accuses Moscow of lying to public about Ukraine". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr; Roth, Andrew (24 June 2023). "Putin accuses Wagner chief of treason and vows to 'neutralise' uprising". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b Gardner, Frank; Greenal, Robert; Lukiv, Jaroslav (23 August 2023). "Wagner boss Prigozhin killed in plane crash in Russia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Armitage, Rebecca (24 June 2023). "Who is Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner warlord and former Putin ally, accused of mounting a mutiny in Russia?". ABC Australia. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Walker, Shaun; Sauer, Pjotr (24 June 2023). "Yevgeny Prigozhin: the hotdog seller who rose to the top of Putin's war machine". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b Helsel, Phil (24 June 2023). "What is the Wagner Group? A look at the mercenary group led by man accused of 'armed mutiny' in Russia". NBC News. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Faulkner, Christopher (June 2022). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). "Undermining Democracy and Exploiting Clients: The Wagner Group's Nefarious Activities in Africa" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 15 (6). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 28–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ "Wagner mutiny: Group fully funded by Russia, says Putin". BBC News. 27 June 2023. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Brimelow, Ben (14 February 2018). "Russia is using mercenaries to make it look like it's losing fewer troops in Syria". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ Mackinnon, Amy (6 June 2021). "Russia's Wagner Group Doesn't Actually Exist". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma (24 June 2023). "Why did Wagner turn on Putin and what does it mean for Ukraine?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b Knickmeyer, Ellen (24 June 2023). "The mercenary chief who urged an uprising against Russia's generals has long ties to Putin". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Brutality of Russia's Wagner gives it lead in Ukraine war". Associated Press. 27 January 2023. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023.

- ^ Doxsee, Catrina; Thompson, Jared (11 May 2022). "Massacres, Executions, and Falsified Graves: The Wagner Group's Mounting Humanitarian Cost in Mali". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b Ehl, David (26 February 2023). "Russia's Wagner Group in Africa: More than mercenaries". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b Diallo, Tiemoko; Yongo, Judicael (24 June 2023). "Wagner revolt clouds outlook for its operations in Africa". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Barnes, Julian E. (24 June 2023). "U.S. Suspected Prigozhin Was Preparing to Take Military Action Against Russia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b Lotareva, Anastasia; Barabanov, Ilya (5 June 2023). ЧВК "Вагнер" задержал подполковника российской армии и заставил извиниться. Что происходит? ["Wagner" detained a lieutenant colonel of the Russian army and forced him to apologize. What's happening]. BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b "A mercenaries' war – How Russia's invasion of Ukraine led to a 'secret mobilization' that allowed oligarch Evgeny Prigozhin to win back Putin's favor". Meduza. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Russia's Wagner mercenaries halt prisoner recruitment campaign - Prigozhin". Reuters. 9 February 2023. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Блеф или военный мятеж? Что означает ультиматум Евгения Пригожина". belsat.eu. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Maynes, Charles (6 March 2023). "Yevgeny Prigozhin, 'Putin's Chef,' has emerged from the shadows with his Wagner Group". NPR. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan (9 February 2023). "Wagner, the Russian mercenary group, says it has stopped recruiting prisoners". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Michael, Starr (21 March 2023). "End of Russian convict contracts may cause Wagner manpower issues". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Kurmanaev, Anatoly; Crichton, Kyle (24 June 2023). "As Putin's Trusted Partner, Prigozhin Was Always Willing to Do the Dirty Work". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Davidoff, Victor (14 October 2022). "Reading the Tea Leaves of Russia's Pro-War 'Z-Universe'". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Nakashima, Ellen; Hudson, John; Sonne, Paul (26 October 2022). "Mercenary chief vented to Putin over Ukraine war bungling". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "Prigozhin's lesser war Now a 'full-fledged member of Putin's inner circle,' the Wagner Group's founder wages a crusade against St. Petersburg's loyalist governor, Alexander Beglov. What does this mean for the future of Putin's regime?". Meduza. 1 November 2022. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b Roscoe, Matthew (11 October 2022). "Putin's ally Yevgeny Prigozhin urges Russian MPs to join Wagner Group on front line". EuroWeekly News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ «Олигархи пытаются украсть все, что принадлежит народу»: Пригожин обвинил бизнес в разворовывании России. Kapital-rus.ru (in Russian). 19 November 2022. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Faulconbridge, Guy (24 May 2023). "Mercenary Prigozhin warns Russia could face revolution unless elite gets serious about war". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "Prigozhin suggests that Russia follow North Korea's example so the country isn't "screwed up"". Ukrainska Pravda. 5 June 2023. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b Stepanenko, Kateryna; Kagan, Frederick W. (12 March 2023). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, March 12, 2023". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Lendon, Brad; Pennington, Josh; Pavlova, Uliana (5 May 2023). "Wagner chief says his forces are dying as Russia's military leaders 'sit like fat cats'". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Knickmeyer, Ellen (24 June 2023). "The mercenary chief who urged an uprising against Russia's generals has long ties to Putin". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan (25 May 2023). "Wagner's Withdrawal From Bakhmut Would Present Test to Russian Army". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Dixon, Robyn; Ables, Kelsey; Bisset, Victoria; Stern, David; Parker, Claire; Abbakumova, Natalia (5 May 2023). "Ukraine live briefing: Head of Russia's Wagner mercenaries lashes out at Moscow; drone attacks target Russian oil refinery". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan (25 May 2023). "Russia-Ukraine War: Russian Mercenary Leader Says His Forces Are Starting to Leave Bakhmut". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023.

- ^ Ljunggren, David (3 June 2023). Wallis, Daniel (ed.). "Russian forces tried to blow up my men, says mercenary boss Prigozhin". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Fredrick W. (3 June 2023). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 3, 2023". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ a b Sauer, Pjotr (5 June 2023). "Wagner captures Russian commander as Prigozhin feud with army escalates". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Wagner Captures Russian Soldier Accused of Firing on Its Positions". The Moscow Times. 5 June 2023. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Sonne, Paul; Kurmanaev, Anatoly (27 June 2023). "His Glory Fading, a Russian Warlord Took One Last Stab at Power". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Chotiner, Isaac (27 June 2023). "What Prigozhin's Half-Baked "Coup" Could Mean for Putin's Rule". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

Tatiana Stanovaya: ... Prigozhin was barely noticeable as a political figure six months ago and has now gained considerable traction. People tend to back victors, but ordinary Russians were also moved by his open clash with the Ministry of Defence and his comments on ammunition shortages.

- ^

- Cuesta, Javier G. (27 June 2023). "Wagner rebellion sharpens divisions in Russia's military forces". EL PAÍS English. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- "Approval of Institutions, Ratings of Politicians: May 2023". Levada Center. 7 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (13 June 2023). "Putin backs push for mercenary groups to sign contracts despite Wagner's refusal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Kirby, Paul (24 June 2023). "Wagner chief's 24 hours of chaos in Russia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "'There's nobody on earth who can stop them' What Wagner Group veterans have to say about Yevgeny Prigozhin's armed rebellion". Meduza. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b "'They thought the risk was nil' Prigozhin's armed rebellion caught Kremlin officials off guard. Meduza's sources say that by all appearances, attempts to negotiate have failed". Meduza. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Sonne, Paul; Kurmanaev, Anatoly (27 June 2023). "His Glory Fading, a Russian Warlord Took One Last Stab at Power". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d Taub, Amanda (26 June 2023). "A Mutiny That Showed the Stress on Putin's System of Rule". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ "'There's nobody on earth who can stop them' What Wagner Group veterans have to say about Yevgeny Prigozhin's armed rebellion". Meduza. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Wagner mercenary leader issues defiant audio statement as uncertainty swirls after mutiny". AP NEWS. 26 June 2023. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Bertrand, Natasha; Marquardt, Alex; Atwood, Kylie; Liptak, Kevin (26 June 2023). "US gathered detailed intelligence on Wagner chief's rebellion plans but kept it secret from most allies". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pancevski, Bojan (28 June 2023). "Wagner's Prigozhin Planned to Capture Russian Military Leaders". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Barnes, Julian E. (24 June 2023). "U.S. Suspected Prigozhin Was Preparing to Take Military Action Against Russia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Barnes, Julian E.; Cooper, Helene; Schmitt, Eric (28 June 2023). "Russian General Knew About Mercenary Chief's Rebellion Plans, U.S. Officials Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.