Pilloo Pochkhanawala

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Pilloo Pochkhanawala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Pilloo Adenwalla 1 April 1923 |

| Died | 7 June 1986 |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | Spark |

| Style | Modernism, Minimalism |

| Spouse | Rattan Pochkhanawala |

| Children | 1 |

Pilloo Pochkhanawala (1 April 1923 – 7 June 1986) was among the first few women sculptors in India.[1] Initially, she worked in advertising before going on to become a sculptor. Through her dynamic works, Pochkhanawala established herself as a pioneer of modern sculpture among her contemporaries.[2] Her pieces were inspired by nature or often took the form of human figures.[3] As a self-taught artist, she employed a variety of media in her artworks including metal, stone and wood among others.[4] Her oeuvre includes intricate drawings, theatrical sets, although she is well known for her sculptures.[5]

In addition to being an artist, Pochkhanawala was also a facilitator and mediator of the arts in Bombay. From the 1960s, she organized the Bombay Art Festival for many years.[1] Along with her fellow artists, she also played a major role in transforming the Sir Cowasji Jehangir Hall into the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, which is now one of the country's leading museums housing contemporary art.[3]

Early life and education[edit]

Born on 1 April 1923, Pilloo was the daughter of Framroze R. Adenwalla and Jerbai.[6] They were a Parsi family who followed the ancient religion of Zoroastrianism. She was brought up in the household of her paternal grandparents in a traditional joint family consisting of three children and eleven grandchildren. Members of her family were the owners of Cowasjee Dinshaw and Brothers. With the head office of their firm in Bombay, their business also extended to Arabia, Africa and Aden. Pochkhanawala visited these places during her childhood, out of which Zanzibar impressed her the most, especially because of its African Voodoo cult rites.[7]

Instead of following the rigid customs of the family, Pochkhanawala was exposed to diverse perspectives in the company of her peers, both in secondary school and college. The struggle for Indian independence was at its peak during her youth. She became a part of cultural and political changes that were happening with the rise of Quit India Movement whilst World War II. In 1945, she received her bachelor’s degree in commerce from Bombay University[8] and went on to work in an advertising firm.[7]

Career[edit]

Working in the advertising industry suppressed Pochkhanawala's urge to draw at her own will. During her time in college, instead of statistics, her books were filled with sketches. It was only after her experience at the advertising agency, she was convinced that visual arts was her real calling.[7]

Foray into sculpture[edit]

In 1951, Pochkhanawala made her first visit to Europe. She was on an assignment to create posters and advertisement displays for the national airline, Air India. This tour gave her an opportunity to visit major museums in the region, where she was amazed by the major works of modern sculptors.

Evidently, it was my sudden grasp of the third dimension that left me mortified by the sculptures... I was mortified by the sculptures because I was seized by the fear of the challenge of tackling something so difficult. I suppose the mind was sorting out the message that was beginning to take shape. I knew that my keen interest in drawing will not by itself lead me on to a discovery of sculptural line, form, volume, void and the like. What made everything so challenging and confusing was my intense and instant admiration for the new sculpture of the time.[9]

This rekindled and further sparked her desire to pursue visuals arts and motivated her to turn into a sculptor. She decided to devote herself entirely to sculpture after returning to Bombay.[7] Pochkhanawala was mentored by N. G. Pansare, who taught her the techniques of sculpting and encouraged her to develop her own style by experimenting with materials.[2] Moreover, a visit to England in 1970 and meetings with renowned sculptors such as Henry Moore, Kenneth Armitage, Barbara Hepworth and Eduardo Paolozzi provided her with an impressionable insight into the meaning of modern sculpture.[9]

Inspiration from Indian art[edit]

Pochkhanawala's visit to temple sites around the country piqued her interest in the art and history of Indian sculpture. She admired the fluidity and liveliness of these sculptures, which had a profound impact on her creations.[10]

Post independence, Ramkinkar Baij (at Santiniketan) and Shanko Chowdhury (at Baroda) took over the responsibility to propagated the new approach to making sculptures. Pochkhanawala, along with Adi Davierwala in Bombay, worked on sculptures that showcased their beliefs and expressed their experience of living in changing India of the 20th century.[7] Both of them explored the industrial developments in their surroundings and evolved new methods of fabrication in their works, like welding. Their choice of material became an important part of the subjects they depicted and the sculptural forms developed by them belonged to a wider global trend.[11]

Style[edit]

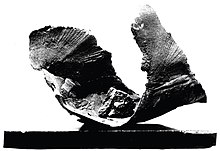

Largely experimental in her approach, Pochkhanawala's oeuvre includes a range of materials and approaches from wood, cement, metal, mesh and transparent sheets, eventually turning to "found" and scrap metal, welding and casting them to make her signature forms.[12] Her early works displayed a marked influence of Henry Moore, which mainly featured figures of seated women in wood.[2] In the 1970s, her sculptures represented rockscapes on sea beaches. The industrial steel scrap was assembled with natural forms of stone which juxtaposed solid forms with fluid shapes.[13]

Work[edit]

Public sculptures[edit]

Pochkhanawala is best remembered for her public sculptures, the most famous of which was called Spark and stood over two storeys tall at the old Haji Ali Circle in Mumbai. Originally commissioned by Brihanmumbai Electricity Supply and Transport (BEST), it was made in her distinct style by welding scrap metal together. It is assumed to have gotten its name from the BEST's connection to electricity and the sculpture's contrast of heavy material and light, bird-like features. The location was important to her as she lived in the area. However, the sculpture had a troubled history, being moved to a smaller circle during her lifetime. It eventually disappeared in a road expansion project in early 1990s. In 2002, a scale model, at one-third the height of the original, was installed through a citizen's initiative, on a traffic island outside the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai. In late 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, the replica was lost in a beautification drive.[14] Another public sculpture of Pochkhanawala is Stone Age To Space, installed at the Nehru Centre. It is made of rough sandstone and cast aluminium.[15]

Other works[edit]

Pochkhanawala had created stage design for five plays, which included Girish Karnad's Tughlaq (1970) and The Book of Job (1976).[10] Along with N. S. Bendre, Kiran Gujral, M. F. Husain, Paritosh Sen and Krishen Khanna, Pochkhanawala was among the six Indian artists who designed new laminates for Formica India.[16] She wrote a piece about The Rodin Exhibition for the NCPA Quarterly Journal which took place from 19 March to 11 April 1983 at the Tata Theatre.[17] In 1984, she was appointed as a member to the Advisory Panel of the Central Board of Film Certification.[18]

Exhibitions[edit]

Pochkhanawala had solo exhibitions from 1955 to 1978 in Bombay, and in Delhi in 1965, 1968 and 1982. Her piece titled Frenzy was exhibited in the Tenth National Exhibition of Art at the Lalit Kala Akademi.[19] The international shows included exhibitions at Minnesota, USA (1980); Middleheim, Belgium (1974); Belgrade; Bangkok; Tokyo (1967) and in London (1963).[8] Her sculptures were showcased at the São Paulo Art Biennial in 1969 and 1971.[20][21]

During one of the modern art exhibitions in Bombay, her sculptures were at display in the Prince of Wales Museum. In his book The Heart of India, Duncan Forbes has written about the moment when Pochkhanawala was talking about her work:

I go to a factory to get all these bits of metal. They call it scrap. Some people don't understand these sculptures, but you know, I have a class of deaf and dumb children I teach, and I brought them round without saying anything to them, and do you know, one of the little girls was standing in front of this one, the Kathakali, and she actually began to do a kind of dance. Isn't that amazing?[22]

Forbes took a second look of the sculpture and realized that the crude shapes of the sculpture indeed had some evocative power. He further wrote that, possibly, it was the crude nature of the artwork that allowed the imagination to be free and experience it fully.[citation needed]

Awards and recognition[edit]

Pochkhanawala received several awards in her lifetime which included a silver medal from the All India Sculptors' Association and another silver medal from Bombay Art Society, both in 1954. This was followed by a couple of prizes at the Maharashtra State Art Exhibition in 1955 and 1961; 1st Prize at the Mumbai State Art Exhibition in 1959 and an award by Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi in 1979.[9]

Personal life[edit]

Pilloo had married Rattan Pochkhanawala and had one child, Meher.[6][23] Her husband belonged to the family of Sir Sorabji Pochkhanawala, one of the founders of the Central Bank of India.[14]

Death and legacy[edit]

Pochkhanawala died on 7 June 1986 due to cancer.[23] In the recent years, she has seen a rise in popularity, with her works appearing in art shows in Mumbai, namely No Parsi is an Island[24] and The 10 Year Hustle.[25] However she remains largely forgotten with her public sculptures lost or unknown. She was one of the earliest proponents of a modernist wave in Indian sculpture, developing a style that moved away from merely making copies of popular figures.[14] Pochkhanawala's Untitled wooden sculpture was sold for ₹77.9 lakh (equivalent to ₹92 lakh or £96,000 in 2023) at the Sotheby's auction of Modern and Contemporary South Asian Art in 2020. This was the highest recorded price for her work, with ₹57 lakh (US$71,000) being the previous best value.[26]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Pilloo Pochkhanawala". JNAF. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Pilloo Pochkhanawala: Sculpting a Legacy (Catalogue Note)". Sotheby's.

- ^ a b "14 Parsi artists dialogue in Delhi – in pictures – ArtRadarJournal.com". Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Yamini Mehta (2 June 2017). "Eternal frames". India Today. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Pilloo Pochkhanawala (1923-1986) - Lot Essay". www.christies.com. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Indian Who's Who 1980-81. New Delhi: INFA Publications. p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e Pochkhanawala, Pilloo R.; Clerk, S. I. (1979). "On My Work as a Sculptor". Leonardo. 12 (3): 192–196. doi:10.2307/1574206. ISSN 0024-094X. JSTOR 1574206. S2CID 147265357.

- ^ a b "Pilloo Pochkanawala". Saffronart. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Vasudev, S. V. (1981). Krishnan, S. A. (ed.). Pilloo Pochkhanawala. New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi.

- ^ a b "Pilloo Pochkhanawala". Marg. 38 (4): 43–48. September 1987.

- ^ Jayaram, Suresh (September 2000). "Abstraction: Nature and the Numinous". Marg. 52 (1): 51.

- ^ "Modern Movement in Indian Sculpture". criticalcollective.in. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Mago, Pran Nath (2000). Contemporary Art in India - A perspective. New Delhi: National Book Trust. p. 124. ISBN 81-237-3420-4.

- ^ a b c Singh, Laxman (23 January 2021). "Mystery of the missing 'Spark' as Thackeray gets statue in Mumbai". ProQuest. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "When your road gets the art attack". Hindustan Times. 21 January 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Six great minds help make on great idea". Seminar (186): 8. February 1975.

- ^ Pochkhanawala, Pilloo R. (June 1983). "The Rodin Exhibition". NCPA Quarterly Journal. 12 (2): 9–20.

- ^ "Ministry of Information and Broadcasting". The Gazette of India (12): 812. 24 March 1984.

- ^ "The Tenth National Exhibition of Art". The Modern Review. 115 (4): 271–272. April 1964.

- ^ "10ª Bienal de São Paulo (1969) - Catálogo by Bienal São Paulo". issuu.com. August 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "11ª Bienal de São Paulo (1971) - Catálogo by Bienal São Paulo". issuu.com. October 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ Forbes, Duncan (1969). The heart of India ([1st American ed.] ed.). South Brunswick [N.J.]: A.S. Barnes. pp. 73–75. ISBN 0-498-07360-2. OCLC 6230.

- ^ a b शिल्पकार चरित्रकोश खंड ६ - दृश्यकला (in Marathi). मुंबई: साप्ताहिक विवेक, हिंदुस्थान प्रकाशन संस्था. 2013. pp. 339–340.

- ^ Jhaveri, Shanay (20 March 2014). "A Larger World". Frieze. No. 162. ISSN 0962-0672. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "The 10 Year Hustle: Celebrating a decade of our gallery space". Chatterjee & Lal. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Das, Soumitra (11 October 2020). "A September to remember for Indian art at auctions". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 7 February 2023.