Opisthopatus roseus

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Opisthopatus roseus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Onychophora |

| Family: | Peripatopsidae |

| Genus: | Opisthopatus |

| Species: | O. roseus |

| Binomial name | |

| Opisthopatus roseus Lawrence, 1947 | |

Opisthopatus roseus is a species of velvet worm in the Peripatopsidae family.[2][3] As traditionally defined, this species is rose pink with 18 pairs of legs.[4][5] Known as the pink velvet worm,[1] it is found only in the Weza Forest, a Mistbelt Forest in South Africa.

Morphology[edit]

Defining characteristics of O. roseus are its signature reddish pink colour and 18 pairs of clawed legs.[6] For pictures of the species, please visit research-grade observations on iNaturalist.

As a member of the Onychophora phylum, O. roseus has a chitin-covered body with numerous papillae that give it hydrophobic qualities and velvety appearance.[7]

Velvet worms have two antennae on the head, two simple-lensed eyes, and touch and smell sensitive hairs on their papillae.[7] Nephridia for excretion and osmoregulation are located at the base of the leg at every leg-bearing segment, except one where reproductive gonopores are located.[8] Gas exchange occurs through spiracles and tracheae, as well as diffusion through the body wall.[8] A pair of modified legs from which they squirt sticky protein-based slime to ensnare prey is called the oral tubes.[9] To handle prey after capture, they have sickle-shaped and toothed jaws on a fleshy pad on the underside of the head.[7]

In Opisthopatus genus, the last pair of legs is not reduced like in Peripatopsis genus, also found in South Africa.[6] The males and females are similar in morphology, although the shape of the genital opening is sexually dimorphic in Opisthopatus.[6]

The size of O. roseus is about 40 mm long and 3.5 mm wide.[6] They are uniform in colour, but legs and ventral side are lighter.[6] Their papillae are more numerous and closely set; they are smaller and arranged more regularly than in O. cinctipes.[6]

Distribution[edit]

O. roseus is endemic to the Ngele mistbelt forest, near the town of Kokstad in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa.[10]

R. F. Lawrence, who described the species in 1947, collected a specimen in this forest in 1945.[6] The only other specimen he collected there was from 1985 and is currently in the collection of the Hamburg University Museum.[6] The genetic voucher specimen was collected by Savel R. Daniels in 2012 and is housed in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University.[11] The collection has both frozen DNA and a “very tiny piece” of the animal.[11]

As of March 2024, GBIF has 18 occurrences of O. roseus.[12] Of these, 77.8% are material samples, 16.7% are preserved specimens, and only 5.6% are human observations.[12] There is only one research-grade observation of the species in iNaturalist, detected in 1995.[13] Due to scarcity of records, O. roseus was considered to potentially have gone extinct in the late 20th century[14] and erroneously listed as extinct by the IUCN in 1996.[15]

Habitat[edit]

Because of the threat of desiccation due to their spiracles being constantly open,[7] velvet worms live in saproxylic environments, like decaying wood logs and leaf litter.[10] They are photonegative (as they are largely nocturnal) and secretive,[7] making them hard to collect.[10]

Although all extant onychophorans are terrestrial, the fossil record shows that they were likely aquatic in the past, transitioning to land in the Ordovician period.[8] Notably, both marine Cambrian[16] and terrestrial Pennsylvanian[17] fossils are remarkably similar to extant velvet worms.

Prey and predators[edit]

Like other velvet worms, O. roseus is a carnivore and feeds on small invertebrates, mainly soil-dwelling arthropods.[18] Once potential prey has been localized using the sensory antennae, the hunter secretes sticky slime, which is produced and stored in large glands, to entangle it.[18] The cuticle is punctured using a pair of jaws homologous to the chelicerae of chelicerates.[18] These are not mandibles, because they belong to the second body segment rather than the fourth.[18] The velvet worm then injects the prey with digestive saliva and sucks in the softened body parts using its pharynx.[18]

The slime is also used in self-defense, startling the potential predators, like birds, centipedes, and spiders[8] to give the worm time to escape.[7]

Life history[edit]

The Opisthopatus genus exhibits matrotrophic viviparity (also called ovoviviparity), in other words the eggs remain inside the uterus until hatching, so hatching and birth happen simultaneously.[19] Since the nutrients are provided by the mother, the eggs have little or no yolk.[19] They have no placental structures nor chorion, but the vitelline envelope persists until birth,[19] which happens after several months of development.[20] The adults mate throughout their lives and year-round, and with the insemination through the body wall, females keep sperm for a single season.[21] Notably, other Onychophora genera lay eggs which hatch after several months,[19] typically in the wetter and hotter season.[21] About 30 young are produced each year that are thought to reach maturity at nine to eleven months and live for six to seven years.[20]

Newborn velvet worms resemble the adults morphologically, but are smaller in size and have weaker integument pigmentation.[19] Although they have the full number of segments at birth, tracheae develop post-embryonically.[19]

After the development of O. cinctipes has been found to resemble the “long germ band” development of some insects, this unusual pattern was attributed to all of Opisthopatus.[22] Long germ insects specify all their segments as one step in the development process.[23] However, the development pattern of O. roseus follows an anterior-to-posterior gradient and is more similar to other velvet worms.[22]

Since pink velvet worms are ecdysozoans, they periodically molt their α-chitinous cuticle in order to grow;[24] the molting process is regulated by ecdysteroid hormones.[19] Unlike many arthropods, velvet worms do not metamorphose.[19]

Genetic data and phylogeny[edit]

There are 19 partial genomic nucleotide sequences and 13 partial protein sequences ascribed to O. roseus in GenBank.[25]

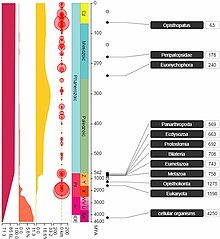

The Opisthopatus genus was described by William Frederick Purcell in 1899 and comprises 12 extant species, including O. roseus.[27] Opisthopatus and Peripatopsis are the two South African genera of the family Peripatopsidae.[10] This family belongs to Euonychophora order, Udeonychophora class, Onychophora phylum, and Panarthropda clade.[28]

Even though O. roseus is a sedentary organism, the population exhibits gene flow, as individuals living closely together exhibit different haplotypes.[10] There are two barcode index numbers (BINs), or barcode sequence clusters, suggesting two distinct genetic groups.[29]

Phylogenetic analysis, however, casts doubt on the traditional species delimitation based on morphology and militates in favor of a broader species definition based on a genetic clade instead. Phylogenetic results indicate that O. herbertorum, described as uniformly white with 17 leg pairs,[30] is a junior synonym of O. roseus.[31] This genetic clade also includes some velvet worms with 16 leg pairs that would traditionally be considered specimens of O. cinctipes. This broader understanding of O. roseus features intraspecific variation in leg number, ranging from 16 to 18 pairs, includes a range of colors from blood red or indigo to pearl white, and entails a broader geographic distribution in the southern part of the Drakensberg Mountains in Kwa-Zulu Natal province of South Africa.[4]

Conservation[edit]

The pink velvet worm was previously considered extinct but is now listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Habitat loss and degradation are thought to be the cause of the species' decline.[1]

The pink velvet worm is endemic to the Ngele forest, which has been significantly disturbed by human activity.[10] In 1890, the construction of a sawmill and subsequent logging of indigenous trees fragmented the habitat.[10] More recently, the N2 national highway bisects the forest.[10] Additionally, commercial timber plantations and introduction of invasive species, as well as the practice of wood removal to minimize forest fires, can further limit the species’ range.[10] Overcollection is unlikely to be a significant threat to the population.[10]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Hamer, M. (2003). "Opisthopatus roseus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2003: e.T15389A4559335. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2003.RLTS.T15389A4559335.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Oliveira, I.; Hering, L. & Mayer, G. "Updated Onychophora checklist". Onychophora Website. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Oliveira, I. S.; Read, V. M. S. J.; Mayer, G. (2012). "A world checklist of Onychophora (velvet worms), with notes on nomenclature and status of names". ZooKeys (211): 1–70. Bibcode:2012ZooK..211....1O. doi:10.3897/zookeys.211.3463. PMC 3426840. PMID 22930648.

- ^ a b Daniels, Savel R.; Dambire, Charlene; Klaus, Sebastian; Sharma, Prashant P. (2016). "Unmasking alpha diversity, cladogenesis and biogeographical patterning in an ancient panarthropod lineage (Onychophora: Peripatopsidae: Opisthopatus cinctipes ) with the description of five novel species". Cladistics. 32 (5): 506–537. doi:10.1111/cla.12154. PMID 34727674. S2CID 49525550.

- ^ Monge-Nájera, Julián (1994). "Reproductive trends, habitat type and body characteristcs in velvet worms (Onychophora)". Revista de Biología Tropical (in Spanish). 42 (3): 611–622. ISSN 2215-2075.

- ^ a b c d e f g h M. L. Hamer; M. J. Samways; H. Ruhherg (1997). A review of the Onychophora of South Africa, with discussion of their conservation.

- ^ a b c d e f "Velvet worm". Australian Museum. December 14, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Wright, Jeremy. "Onychophora (velvet worms)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Lipscombe-Southwell, Alice (July 4, 2022). "What is a velvet worm?". BBC Science Focus. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Daniels, Savel R. (October 2011). "Genetic variation in the Critically Endangered velvet worm Opisthopatus roseus (Onychophora: Peripatopsidae)". African Zoology. 46 (2): 419–424. doi:10.1080/15627020.2011.11407516. ISSN 1562-7020. S2CID 52888175.

- ^ a b University, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard. "MCZbase MCZ:IZ:131344 specimen record | MCZbase". mczbase.mcz.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Opisthopatus roseus occurrences". Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

- ^ Herbert, Dai (August 2014). "Pink Velvetworm (Opisthopatus roseus)". iNaturalist. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ The IUCN Invertebrate Red Data Book. [s.n.] 1983. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.45441.

- ^ Baillie, Jonathan (1996). 1996 IUCN red list of threatened animals. Gland, Switzerland : IUCN ; Washington, D.C., U.S.A. : Conservation International. p. 187. ISBN 2831703352.

- ^ "Fossil Record of the Onychophora". ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ^ Thompson, Ida; Jones, Douglas S. (1980). "A Possible Onychophoran from the Middle Pennsylvanian Mazon Creek Beds of Northern Illinois". Journal of Paleontology. 54 (3): 588–596. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1304204.

- ^ a b c d e Mayer, Georg; Oliveira, Ivo S.; Baer, Alexander; Hammel, Jörg U.; Gallant, James; Hochberg, Rick (August 2015). "Capture of Prey, Feeding, and Functional Anatomy of the Jaws in Velvet Worms (Onychophora)". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 55 (2): 217–227. doi:10.1093/icb/icv004. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 25829018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mayer, Georg; Franke, Franziska Anni; Treffkorn, Sandra; Gross, Vladimir; de Sena Oliveira, Ivo (2015), Wanninger, Andreas (ed.), "Onychophora", Evolutionary Developmental Biology of Invertebrates 3: Ecdysozoa I: Non-Tetraconata, Vienna: Springer, pp. 53–98, doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-1865-8_4, ISBN 978-3-7091-1865-8, retrieved 2024-02-25

- ^ a b "Pink velvet worm articles - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ a b Monge, Julián (2019-02-05). "Two ways to be a velvet worm". Revista de Biología Tropical: Darwin. doi:10.15517/rbt.v0i1.36107. ISSN 2215-2075.

- ^ a b Mayer, Georg; Bartolomaeus, Thomas; Ruhberg, Hilke (January 2005). "Ultrastructure of mesoderm in embryos of Opisthopatus roseus (Onychophora, Peripatopsidae): Revision of the "long germ band" hypothesis for Opisthopatus". Journal of Morphology. 263 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1002/jmor.10289. ISSN 0362-2525. PMID 15536644.

- ^ Liu, Paul Z.; Kaufman, Thomas C. (November 2005). "Short and long germ segmentation: unanswered questions in the evolution of a developmental mode". Evolution & Development. 7 (6): 629–646. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05066.x. ISSN 1520-541X. PMID 16336416.

- ^ Mayer, Georg (2016). Structure and Evolution of Invertebrate Nervous Systems. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199682201.003.0032.

- ^ "Opisthopatus roseus". NCBI. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ "TimeTree :: The Timescale of Life". timetree.org. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ "Opisthopatus Purcell, 1899". www.gbif.org. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ^ "Opisthopatus roseus". NCBI Taxonomy Browser.

- ^ "Bold Systems v4". www.boldsystems.org. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Ruhberg, Hilke; Hamer, Michelle L. (2005). "A new species of Opisthopatus Purcell, 1899 (Onychophora: Peripatopsidae) from KwaZulu–Natal, South Africa". Zootaxa. 1039: 27–38. doi:10.5281/zenodo.169797 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "ITIS - Report: Opisthopatus roseus". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

Further reading[edit]

- Daniels, S. R. (2011). "Genetic variation in the Critically Endangered velvet worm Opisthopatus roseus (Onychophora: Peripatopsidae)". African Zoology. 46 (2): 419–424. doi:10.1080/15627020.2011.11407516. hdl:10019.1/22007. S2CID 219289726.

- Mayer, G.; Bartolomaeus, T.; Ruhberg, H. (2005). "Ultrastructure of mesoderm in embryos of Opisthopatus roseus (Onychophora, Peripatopsidae): Revision of the "long germ band" hypothesis for Opisthopatus". Journal of Morphology. 263 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1002/jmor.10289. PMID 15536644. S2CID 33663506.