Isa Kelemechi

ʿIsa Tarsah Kelemechi[1] (simplified Chinese: 爱薛; pinyin: Àixuē, fl. 1248–1312) was a Church of the East astronomer and physician[2] at the Yuan court of Kublai Khan's Mongol Empire in the 13th century.

Astrologer in China[edit]

ʿIsa was named head of the Office of Western Astronomy established by Kublai Khan in 1263 to study Islamic astronomical observations.[3] Kubilai would establish a Observatory for Islamic astronomy in 1271, directed by astronomer Jamal ad-Din Bukhari.[3]

ʿIsa was also instrumental in reinforcing anti-Muslim prohibitions in the Mongol realms, such as prohibiting halal slaughter and circumcision, and, according to Rashid-al-Din Hamadani encouraged denunciation of Muslims.[4] ʿIsa also showed to Khubilai the Sword Verse of the Quran, raising the suspicion of the Mongols towards Muslims.[4] According to Rashid al-Din, as a result, "most Muslims left Khitai [China]".[4]

Diplomat to Europe[edit]

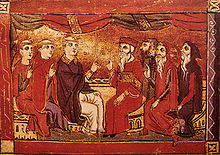

Isa Kelemechi was later a member of the first mission to Europe sent by Arghun, the Il-Khan in 1285. He met with Pope Honorius IV, remitting a letter from Ghazan offering to "remove" the Saracenz and divide "the land of Sham, namely Egypt" with the Franks.[5][6] The message, written in imperfect Latin, said:

"And now let it be [says the Il-Khan], because the land of the Saracens is not ours, between us, good father, us who are on this side and you who are on your side; the land of Scami [Sham] to wit the land of Egypt between you and us we will crush. We send you the said messengers and [ask] you to send an expedition and army to the land of Egypt, and it shall be now that we from this side shall crush it between us with good men; and that you send us by a good man where you wish the aforesaid done. The Saracens from the midst of us we shall lift and the Lord Pope and the Cam [Great Khan Qubilai] will be lords".

— Message from Arghun to Pope Honorius IV.[6]

The 1285 embassy would be followed in 1287 by that of Rabban bar Sauma.[5]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1, pp. 125–126

- ^ Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- ^ a b Thomas F. Glick; Steven John Livesey; Faith Wallis (2005). Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia p.485. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96930-1.

- ^ a b c Richard Foltz (2000). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange p.125ff. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.

- ^ a b Peter Jackson (2005). The Mongols and the West, 1221-1410 p.169. Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-36896-0.

- ^ a b William Bayne Fisher; John Andrew Boyle (1968). The Cambridge history of Iran p.370. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06936-X.