Sex determination

Sex determination is a process of development by which the sex of an individual is settled. Sex is a method of reproduction which is widespread among living things. It requires two individuals of the same species.

Usually, the sexes are separate. Sex may be determined in one of two ways:

- Genetically, by genes and chromosomes the organism inherits from its parents.

- Environmentally, by some outside agent acting as a trigger to development.[1]

Where both sexes occur on the same individual, that individual is an hermaphrodite. Hermaphrodite systems can be found in some animals, for example snails, and in most flowering plants.[2]

Determination by the environment[change | change source]

For many species, sex is determined by environmental factors experienced during development. Many reptiles have temperature-dependent sex determination. The temperature embryos experience during their development determines the sex of the organism. In some turtles, for example, males are produced at lower incubation temperatures than females; this difference in critical temperatures can be as little as 1-2 °C.

Many fish change sex over the course of their life. This phenomenon is called sequential hermaphroditism. In clownfish, smaller fish are male, and the dominant and largest fish in a group becomes female. In many wrasse the opposite is true–most fish are female at birth and become male when they reach a certain size. Sequential hermaphrodites may produce both types of gametes over the course of their lifetime, but at any given point they are either female or male.[3]

In some ferns the default sex is hermaphrodite, but ferns which grow in soil that has previously supported hermaphrodites are influenced by hormones remaining to develop as male.[4]

Genetic determination[change | change source]

The most usual way to determine sex is by genes. That way, an organism's sex is determined by the genome it gets. The alleles that influence sexual development may or may not be on the same chromosome. If they are, that chromosome is called a sex chromosome, and the genes on it are called 'sex linked'. Sex is determined either by the fact that there is a sex chromosome (which can be missing), or by the number of them. Because genetic sex determination is determined by matching chromosomes, there are usually the same number of male and female offspring.

Various genetic systems[change | change source]

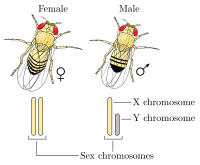

Humans and other mammals have an XY sex determination system: the Y chromosome carries factors responsible for male development. The default sex, in the absence of a Y chromosome, is female. XX mammals are female and XY are male. XY sex determination is also found in other organisms, including the common fruit fly and some plants.[2] In some cases, including in the fruit fly, it is the number of X chromosomes that determines sex rather than the presence of a Y chromosome.

Birds have a system that works the other way round: It is called ZW sex-determination system. The W chromosome has factors for female development. By default (if the chromosome is missing), the organism will be male.[5] In this case, ZZ individuals are male and ZW are female. The majority of butterflies and moths also have a ZW sex-determination system. In both XY and ZW sex determination systems the sex chromosome carrying the critical factors is often significantly smaller, carrying little more than the genes necessary for triggering the development of a given sex.[6]

Many insects use a sex-determination system based on the number of sex chromosomes. This is called XX/XO sex determination–the O indicates the absence of the sex chromosome. All other chromosomes in these organisms are diploid, but organisms may inherit one or two X chromosomes. Infield crickets, for example, insects with a single X chromosome develop as male, while those with two develop as female.[7] In the nematode C. elegans most worms are self-fertilizing XX hermaphrodites, but occasionally abnormalities in chromosome inheritance regularly give rise to individuals with only one X chromosome–these XO individuals are fertile males (and half their offspring are male).[8]

Other insects, including honey bees and ants, use a haploid-diploid sex-determination system.[9] In this case diploid individuals are generally female, and haploid individuals (which develop from unfertilized eggs) are male. This sex-determination system results in a highly biased sex ratio, as the sex of offspring is determined by fertilization rather than the assortment of chromosomes during meiosis.[10]

Abnormalities[change | change source]

Sometimes an organism develops the appearance of both males and females. It is then an intersex and is rare. Even though such organisms may be called hermaphrodites, this is not correct, because in intersex individuals either the male or the female aspect is sterile.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ King R.C. Stansfield W.D. & Mulligan P.K. 2006. A dictionary of genetics, 7th ed. Oxford.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dellaporta SL, Calderon-Urrea A (1993). "Sex determination in flowering plants". The Plant Cell. 5 (10): 1241–1251. doi:10.2307/3869777. JSTOR 3869777. PMC 160357. PMID 8281039.

- ↑ Munday, Philip L; Buston, Peter M; and Warner, Robert R. 2006. Diversity and flexibility of sex-change strategies in animals. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 21, February. [1]

- ↑ Tanurdzic M and Banks JA (2004). "Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants". The Plant Cell. 16 (Suppl): S61–S71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- ↑ Smith CA, Katza M, Sinclair AH (2003). "DMRT1 is upregulated in the gonads during female-to-male sex reversal in ZW Chicken Embryos". Biology of Reproduction. 68 (2): 560–570. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.007294. PMID 12533420. S2CID 13436922.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Evolution of the Y chromosome". Annenberg Media. Archived from the original on 2004-11-04. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ Yoshimura A (2005). "Karyotypes of two American field crickets: Gryllus rubens and Gryllus sp. (Orthoptera: Gryllidae)". Entomological Science. 8 (3): 219–222. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8298.2005.00118.x. S2CID 84908090.

- ↑ Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR (1997). C. Elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-532-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)9.II. Sexual Dimorphism - ↑ Charlesworth B (2003). "Sex Determination in the Honeybee". Cell. 114 (4): 397–398. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00610-X. PMID 12941267. S2CID 18839759.

- ↑ White M.J.D. 1973. The chromosomes. 6th ed, Chapman & Hall, London.