Reign of Alfonso XII

The reign of Alfonso XII of Spain began after the Pronunciamiento de Sagunto on December 29, 1874, which ended the First Spanish Republic. It lasted until his death on November 25, 1885, after which his wife, María Cristina of Habsburg, assumed the Regency. During his reign, the political regime of the Restoration was established, based on the Spanish Constitution of 1876, which remained in effect until 1923.[1][2] The regime was a constitutional monarchy, though neither democratic nor parliamentary,[3] described by supporters as liberal and by critics, particularly regenerationists, as oligarchic. Its foundations were based on doctrinaire liberalism, as noted by Ramón Villares.[4]

Carlos Dardé described the reign as brief but significant, with Spain's situation improving in various areas by its end. Despite uncertainty following the king’s death, the improvements continued under María Cristina's regency during the minority of her son, Alfonso XIII. The foundations of the liberal regime were solidified during this period.[5][6]

The reign saw economic growth, driven by the expansion of the railway network, foreign investments, the mining boom, and increased agricultural exports, especially wine, due to the phylloxera plague devastating French vineyards.[7] The nobility and high bourgeoisie benefited most from this growth, forming a "power bloc" intertwined with the political elite.[8][9][10] Meanwhile, Spain remained largely agrarian, with two-thirds of the population working in the primary sector and a small middle class, while millions of poor laborers, especially in the south, lived in poverty.[11][12]

Background

[edit]Exile and abdication of Isabella II to her son Alfonso (1868-1873)

[edit]

The Glorious Revolution of September 1868 ended the reign of Isabella II and began the Sexenio Democrático.[13][14] The queen, who was in San Sebastian, fled Spain and went into exile in France under the protection of Emperor Napoleon III, accompanied by her daughters and her son, Alfonso, the Prince of Asturias. They settled in the Basilewsky Palace in Paris, which Isabella renamed the Palace of Castile.[15][16][17][18] Prince Alfonso was enrolled in the prestigious Stanislas School, where his political education was guided by his tutor, Guillermo Morphy.[19]

In February 1870, the prince traveled to Rome to receive his first communion from Pius IX. However, the pope did not publicly recognize the Bourbon dynasty as the legitimate heirs to the Spanish throne or condemn the "revolutionary regime" in Spain, as Isabella had hoped.[20][21][22] Instead, of the 43 Spanish bishops attending the First Vatican Council, 39 visited the prince, and Cardinal Juan Ignacio Moreno y Maisonave, prepared him for the Eucharist.[23][24]

Meanwhile, in Madrid, a Provisional Government led by General Serrano called elections to the Constituent Courts, which approved a new "democratic" Constitution in June 1869. General Serrano assumed the Regency while General Prim, who was tasked with finding a candidate for the Spanish throne, served as president of the government.[25][26]

To advocate for her restoration, Isabella appointed Juan de la Pezuela, Count of Cheste, a moderate traditionalist, but he soon resigned after members of the Moderate Party criticized her for surrounding herself with the same people who had contributed to her loss of the throne.[27] Among Bourbon supporters, there was growing support for the idea that the restoration could only occur if Isabella abdicated in favor of her son, Alfonso. Isabella sought consultations on the matter, and while a small group of her close friends and neo-Catholic supporters opposed abdication, most moderates and unionists favored it. Some, like the Marquis of Molins, hoped a new prince would inspire "more hopes than memories".[28][29][30][31] Among those in favor of abdication was a small group of deputies from the Constituent Courts, led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, who would later form the Conservative Party of the Restoration.[32][33] Cánovas suggested to Isabella that it would be advantageous for her dynasty to be represented by a new, well-educated prince, detached from the current political turmoil.[34]

I have come to abdicate freely and spontaneously, without any kind of coercion or violence, driven solely by My love for Spain and its fortune and independence, from the royal authority that I exercised by the grace of God and the Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy promulgated in the year 1845, and to abdicate also all My merely political rights, transmitting them with all those that correspond to the succession of the Crown of Spain to My beloved Son Don Alfonso, Prince of Asturias.[25]

Isabella II took a year to decide on her abdication, resisting pressure during this time.[35][36] On June 20, 1870, she abdicated the throne in favor of her twelve-year-old son Alfonso in a ceremony held at the Palace of Castile.[37][38][39] The abdication was prompted by the willingness of Prussian Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen to accept the Spanish throne, following a proposal from General Prim.[40] However, the immediate catalyst was the threat from Napoleon III, who opposed both the Prussian candidacy and the Duke of Montpensier's candidacy, which could have led to war with Prussia and the fall of the French Empire after its defeat in 1870.[37][38][41] After the proclamation of the French Republic, Isabella, Alfonso, and the Infantas left Paris for Geneva, where they stayed until August 1871 before returning to France. Prince Alfonso’s education was initially overseen by Tomás O'Ryan, who was replaced by Guillermo Morphy in December 1871.[42]

With the Prussian option discarded, on November 16, 1870, the Spanish Cortes elected Prince Amadeo of Savoy, second son of the King of Italy, as King Amadeo I.[43][44] While the Moderate Party advocated for the return to pre-1868 conditions, the small group led by Cánovas remained cautious but eventually supported Alfonso’s cause after the Republic was declared in February 1873.[45][46][47][48][49][50][51] From that point, Cánovas became the chief spokesperson for "Alfonsism".[52]

Isabella II abdicated without appointing a guardian for Prince Alfonso, so she continued in that role until January 1872, when her brother-in-law, the Duke of Montpensier, took over after negotiating terms with Queen María Cristina, whom Isabella had delegated family affairs to.[37][38][53][54] Montpensier’s efforts to secure military support, particularly from General Serrano, were unsuccessful, and he resigned in January 1873. Isabella then regained guardianship over Alfonso. In February 1872, as part of the "Cannes agreement," Alfonso was sent to study at the prestigious Theresianum Academy in Vienna.[55][56][57] During a visit to the Montpensier family castle in Randan at Christmas 1872, Alfonso met their daughter, María de las Mercedes, whom he married for love in 1878.[58]

Cánovas at the head of the Alfonsina cause (1873-1874)

[edit]

A decisive step toward the Alfonsine restoration occurred on August 22, 1873, amid the cantonal rebellion and shortly after the return of Carlist pretender Carlos VII to Spain, which intensified the third Carlist war. On that date, Isabella II, despite her personal dislike for him,[59] entrusted Antonio Cánovas del Castillo with leadership of the Bourbon dynastic cause.[45][46][47][48][49][60] As Carlos Dardé notes, the letter confirming Cánovas’s appointment—signed by both Isabella and Prince Alfonso, per Cánovas’s condition—constituted explicit approval of his conduct during the revolutionary period.[61] Cánovas rejected any politics of revenge and advocated inclusivity. He wrote: “I will not ask the one who comes [to our side] what he has been; it will be enough for me to know what he intends to be.” He believed in using what was valuable from the revolution that had deposed Isabella II and warned that attempting to restore the past would damage the monarchy.[62] As José Varela Ortega observed, for Cánovas, reconciliation was a victory; revenge, a defeat.[63]

Isabella also granted Cánovas full authority over Alfonso’s education. He decided the prince should begin military training to become a "King-soldier" and gain the confidence of the armed forces.[64][65] Although his preceptor, Guillermo Morphy, resisted the change—arguing the prince should complete his training at the Theresianum in Vienna—Cánovas prevailed,[66] in October 1874, with the agreement of both Alfonso and his mother, Cánovas sent the prince to the British Royal Military Academy of Sandhurst in Britain.[67][68] Alfonso had preferred university education to better prepare for constitutional rule, but Cánovas believed it was more urgent to immerse him in a constitutional environment. Isabella appeared to embrace Cánovas’s vision that the restoration should rely on uniting all liberal factions, in contrast to the exclusionary politics of her reign.[69] In a letter, she wrote: "Your idea is my idea... without this union of all the parties in the shadow of my son's flag... the ruin of Spain is inevitable." As Isabel Burdiel noted, her support was crucial in convincing the moderates to accept Cánovas's leadership.[70]

The Canovist camp expanded to include former Unionists and even some former revolutionaries of 1868, such as Francisco Romero Robledo.[71][72] This alliance gained key backing from the social and economic elites, especially business sectors in Catalonia and Madrid with colonial interests. Their support was vital to consolidating the Alfonsine movement.[73] Historian Manuel Suárez Cortina emphasizes that fears sparked by the Parisian Commune and the association of revolution with democracy led conservative forces—including the Army, the Church, and the middle and upper classes—to view Alfonso XII and the Restoration as a path to stability and order, aligned with international trends and elite interests.[74]

Although Cánovas rejected a traditional military pronunciamiento, insisting that the monarchy should return through broad political consensus, he maintained contact with military leaders.[75][76][45] As Suárez Cortina explains, Cánovas believed the restoration must be politically prepared, with military intervention playing only a secondary, supportive role once that groundwork was in place.[77]

Cánovas del Castillo articulated his strategy for the Bourbon restoration in letters to former Queen Isabella II and Prince Alfonso in January 1874, following the Pavía coup d'état. Some generals associated with the Moderate Party had attempted to use the coup as a pretext to proclaim Alfonso king, but Cánovas dissuaded them.[78][79] In these letters, he emphasized the need to build strong public support for Alfonso through “calm, serenity, patience, perseverance, and energy".[46] In April, he reiterated to Isabella that they must “prepare opinion broadly” and wait for a spontaneous surge of support—“a surprise, an outburst of opinion”—to seize the opportunity without wasting it.[80]

To shape public opinion, Cánovas promoted the establishment of Alfonsino circles across the country and supported the acquisition of newspapers aligned with the cause, such as La Época in Madrid.[81][82] According to historian Manuel Suárez Cortina, Alfonsism quickly became fashionable among the clergy, upper-class women, the bourgeoisie, and large sectors of the Army. Social gatherings and salons played a vital role in spreading the movement, a dynamic dubbed by the British ambassador as the “Ladies’ Revolution".[83][84] Among the key supporters of the Canovist project was the influential Spanish-Cuban lobby, including the so-called slaveholding interest led by the Marquis of Manzanedo. This group, which also included Queen Mother María Cristina—owner of a Cuban sugar plantation—was deeply concerned about the potential abolition of slavery.[85][86] It maintained a vast network of Spanish-Ultramarine circles and clubs, both in Spain and in Cuba, and had strong ties to the military. This faction, led by figures such as the Count of Valmaseda (a former Captain General of Cuba), played a pivotal role in the conspiracy that culminated in the pronunciamiento of Sagunto, which enabled the restoration.[87][88]

After the establishment of the unitary Republic under General Serrano, following the Pavía coup in January 1874, conspiratorial activity in favor of the Bourbon restoration intensified. As historian Feliciano Montero notes, Cánovas's challenge was not to prevent military intervention, but to control and subordinate it to his broader, conciliatory, and non-revanchist vision.[89] He relied particularly on General Manuel Gutiérrez de la Concha, a respected officer not affiliated with the Moderate Party, who commanded the Army of the North in the Carlist strongholds of the Basque Country and Navarre. Their plan was to declare Alfonso king after capturing Estella, the Carlist capital, following the successful capture of Bilbao in May 1874. However, the plan failed when General Concha was killed during the siege of Estella, which ultimately did not fall.[90][91][92][93] Cánovas distrusted General Martínez Campos, who would eventually carry out the pronunciamiento of Sagunto, because of his ties to the Moderate Party and its differing vision for the monarchy. Nevertheless, the military action proceeded.[89] When Cánovas met with Isabella II in Paris on August 8 and 14, he reaffirmed that Alfonso’s restoration should arise from a broad-based movement of public opinion, not from a military coup.[48][94]

Manifesto of Sandhurst

[edit]

On December 1, 1874, three days after Prince Alfonso’s seventeenth birthday, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo launched a decisive step toward the Bourbon restoration with the publication of the Sandhurst Manifesto.[95][96][97][98] Carefully drafted by Cánovas and signed by the prince, the document took the form of a letter written from the British Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, where Alfonso had enrolled in October at Cánovas’s initiative to strengthen his constitutional image.[99][100][101] The letter was framed as a response to the many birthday greetings the prince had received from Spain.[102]

Although written by Cánovas, the manifesto was reviewed by several individuals, including former Queen Isabella II, who discussed it extensively, according to Cánovas.[103][104][105] The text was circulated in various European newspapers, but deliberately not sent to any reigning monarchs. Cánovas's aim, as he explained to Isabella, was to convey that Spain already had a king "capable of wielding power as soon as he is called".[105]

In the manifesto, Prince Alfonso offered the restoration of a "hereditary and representative monarchy" in his person, presenting himself as "the only representative of the monarchical right in Spain." He argued that the monarchy was the only remaining institution capable of restoring confidence in a nation that was, in his words, "orphaned of all public right and indefinitely deprived of its liberties".[100] The letter concluded with a personal pledge: "Whatever my own fate may be, I will not cease to be a good Spaniard, nor, like all my ancestors, a good Catholic, nor, as a man of the century, truly liberal".[106][107][108][109]

Historians broadly agree that the Sandhurst Manifesto encapsulated the core principles of the Restoration regime. According to Ramón Villares, the document represented the political pact among the various Alfonsist factions by the end of 1874. It served both to legitimize the Bourbon alternative and to outline the political project behind Prince Alfonso’s candidacy, presenting its framework to both Spanish society and the international community.[103]

Fall of the Republic and proclamation of Prince Alfonso as king

[edit]Pronunciamiento of Sagunto

[edit]

Although Antonio Cánovas del Castillo had hoped to restore the monarchy through broad public consensus rather than a military coup,[110] events unfolded differently. In the early hours of December 29, 1874, General Arsenio Martínez Campos declared in Sagunto in favor of restoring the Bourbon monarchy under Prince Alfonso de Borbón, effectively proclaiming him King of Spain.[47][102][111] As Ramón Villares noted, this was "the event that was expected in the flag rooms and aristocratic salons adorned with the fleur-de-lis.[47]

The pronunciamiento was driven by generals associated with the Moderate Party, led by the Count of Valmaseda. These figures had opposed the Sandhurst Manifesto, viewing it as overly shaped by Cánovas’s personal ideas rather than those of the prince. The manifesto's publication hastened their plans. Valmaseda, a former Captain General of Cuba, had close ties to Martínez Campos and the powerful Spanish-Cuban lobby. This group, deeply invested in preserving the colonial order and slavery in Cuba, feared that the war on the island could lead to a revolution similar to Haiti’s—something they warned against in a manifesto from the Spanish nobility.[112]

Martínez Campos had only around 1,800 troops, and no major force had formally committed to his cause.[113] The success of the pronunciamiento was largely due to the support of General Joaquín Jovellar, commander of the Army of the Center, who chose to back the movement.[114][115] Jovellar justified his decision in a telegram to the Minister of War, stating that "a sentiment of elevated patriotism [...] and the need to keep the Army united" had compelled him to lead the effort to avoid further anarchy.[116] Martínez Campos sent similar telegrams urging acceptance of the new situation to end civil unrest and restore stability.[117]

The government of Práxedes Mateo Sagasta initially prepared to resist the uprising. On the night of December 30, Sagasta communicated via telegraph with General Serrano, President of the Executive Power of the Republic, who was in northern Spain preparing an offensive against the Carlists.[118] However, Serrano admitted he lacked the loyal forces needed to defend the capital once Jovellar’s defection became known. In a final message, he stated: "Patriotism forbids me to have three governments in Spain [his own, the Alfonsist, and the Carlist]," and soon after crossed into France.[118][119][120]

Almost simultaneously, General Fernando Primo de Rivera, Captain General of Madrid and initially loyal to the Republic, informed Sagasta that the Madrid garrison had joined the movement. He added that a new government would be formed, while Alfonsist troops had already secured key positions in the capital and surrounded the Ministry of War, where the cabinet was in session. At 11 p.m. on December 30, 1874, Sagasta handed over power. The pronunciamiento that began in Sagunto had succeeded, marking the end of the First Republic and the beginning of the Bourbon Restoration under Alfonso XII.[118][121][120]

Formation of the Ministry-Regency and arrival of Alfonso XII in Spain

[edit]

On December 31, 1874, a Ministry-Regency was formed under the leadership of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, who had remained under nominal "detention" in the civil government building of Madrid during the pronunciamiento, along with other prominent Alfonsists. There, General Primo de Rivera visited him and pledged full support. Cánovas, though initially reluctant, declared:[122][123] "I have wished the Restoration in another way, but in view of the attitude of the Army and the unanimous opinion of the country, I accept and assume the procedure; I cannot oppose it; it is my duty; the Restoration is a fact".[124][125] A telegram was sent to Queen Isabella II informing her that her son had been proclaimed King of Spain "without struggle or bloodshed" by the Army of the Center, the Army of the North, the Madrid garrison, and provincial forces. At the time, Prince Alfonso was in Paris with his mother and sisters, having arrived from London the previous day, unaware of the developments. In a letter to his mother, he had stated his intention to return to Sandhurst after the Epiphany.[126][97][127][128]

Isabella II received the telegram early on December 31 and showed it to her son, who had already heard rumors of the pronunciamiento the night before via an anonymous note while attending a theatre performance. Nevertheless, Alfonso delayed his response for five days—according to historian Carlos Seco Serrano, likely to confirm the stability of the new situation.[129][130] His official reply, published in the Gaceta de Madrid on January 6, 1875, confirmed his acceptance and authority. He reaffirmed the principles of the Sandhurst Manifesto and called for national reconciliation, true liberty, and the start of a new era of peace and prosperity. The reference to "true freedom" displeased some elements of the Moderate Party.[131][132][133]

Cánovas advised that Alfonso should return to Spain alone, without his mother or the Duke of Montpensier.[129][134] In a later letter, he bluntly explained to Isabella II that her presence would symbolize the past: "Your Majesty is not a person, you are a reign, a historical epoch, and what the country needs is another reign and another epoch different from the previous ones".[135] Alfonso XII arrived in Barcelona on January 9, 1875, from Marseilles aboard the Navas de Tolosa, welcomed by General Martínez Campos and large crowds. In a public address, Alfonso expressed pride in the title Count of Barcelona and affection for Catalonia.[136] His arrival was marked by a Te Deum in the cathedral and a gala at the Gran Teatro del Liceo. He telegraphed his mother: "The reception that Barcelona has given me exceeds my hopes, would exceed your wishes [...]". He departed for Valencia the next day and then traveled by train to Madrid, arriving on January 14.[137] His entrance into the capital was widely described as “apotheosic” in the press.[138][139] However, historian Carlos Dardé has noted that the Restoration did not generate widespread enthusiasm. Contemporary observers often remarked not on popular excitement, but rather on the general indifference with which most Spaniards greeted both the fall of the Republic and the return of the monarchy.[140]

Upon arriving in Madrid, Alfonso XII confirmed the government formed in his name by Cánovas del Castillo on December 31. The cabinet included both loyal supporters—such as Pedro Salaverría (Treasury) and the Marquis of Molins (Navy)—and notable figures from the Sexenio Democrático, including Francisco Romero Robledo (Interior), Adelardo López de Ayala (Overseas Territories), and General Jovellar (War), representing the military. Cánovas aimed to pursue a "liberal but conservative" policy, avoiding both democratic radicalism and reactionary Carlist influence. The cabinet also included a representative of the Moderate Party, the Marquis of Orovio (Development).[141][142][143] Cánovas excluded prominent Moderates such as General Martínez Campos and Count of Valmaseda from ministerial posts, instead appointing them to military commands in Catalonia and Cuba, distancing them from Madrid.[143][144][145][146] Many moderates declined to join the government upon learning they would be grouped with "septembrinos" and that the Constitution of 1845 would not be restored. Claudio Moyano, a leading moderate, rejected collaboration on these grounds.[147][148]

Shortly after his arrival in Madrid, Alfonso XII traveled to the northern front, assuming the symbolic role of "soldier-king." In Peralta (Navarre), he appealed to Carlists for peace, offering reconciliation while warning that the war they waged was unjustified. His "Proclamation of Peralta" had little effect, and the conflict continued for another year. On his return, he visited Logroño and greeted General Baldomero Espartero, a gesture signaling openness to all liberal factions.[149][150][151] Alfonso had already made clear his intent to rule as a monarch for all Spaniards. In response to a speech by the Archbishop of Valencia evoking Visigothic and Habsburg heritage, he asserted his goal to bring peace, justice, and freedom to all Spaniards, not to rule as a partisan king. Cánovas later expressed admiration for the young monarch, praising his sincerity and sense of duty, and predicted a reign free from favoritism.[152][153]

During his two-week stay at the front, Alfonso faced danger on at least one occasion. Upon returning to Madrid on February 13, he made overtures to former September revolutionaries. He decorated Dr. Pedro González de Velasco, a known leftist, met with General Serrano, the last head of the Republic, and hosted a banquet attended by Constitutional Party leaders, including Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, the last republican prime minister. Both Serrano and Sagasta expressed willingness to cooperate in order to defeat Carlism.[154][155] On January 5, shortly after Martínez Campos's pronunciamiento, La Iberia, the Constitutional Party's newspaper, had expressed willingness to support the new monarchy in exchange for action against Carlism and the Cuban insurrection.[156] A year later, in a speech before the Cortes, Alfonso XII acknowledged the role of constitutionalists in stabilizing the country before his accession.[157]

However, Radical Republican leader Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla remained opposed to the regime and was expelled from Spain in February for alleged conspiratorial activity.[158] Journalist Ángel Fernández de los Ríos, despite his past friendship with Cánovas, was also banished.[155]

First government of Cánovas del Castillo (1875-1881): creation of the political regime of the Restoration

[edit]The Liberal-Conservative Party governed from 1875 to 1881, with Antonio Cánovas del Castillo serving as head of government for most of the period, except during two brief intervals when he resigned for strategic reasons. The first occurred between September and December 1875, when he temporarily ceded the presidency to General Jovellar to distance himself from the responsibility of calling general elections by universal suffrage, which he opposed. The second was from March to December 1879, when General Martínez Campos assumed leadership to avoid Cánovas overseeing two consecutive electoral processes and to implement the Peace of Zanjón, which Cánovas preferred not to manage. Cánovas returned to power after Martínez Campos resigned due to parliamentary resistance to his proposed colonial and military reforms following the 1879 elections.[159][160][161]

The liberal opposition, led by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, criticized the prolonged conservative rule, describing it as "an authoritarianism bordering on dictatorship".[160] From January 1875 to January 1877, Cánovas governed under a regime of exception with restricted civil liberties, a period often referred to as the "dictatorship of Cánovas." This regime persisted beyond the enactment of the 1876 Constitution and only ended with the passage of the Law of January 1877, which imposed limited regulation of freedoms and retroactively justified the state of exception.[162]

The political project of Cánovas and the struggle with the Moderate Party

[edit]

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo's ―primary objective was to consolidate and stabilize the liberal State through a constitutional monarchy,[163] as outlined in the Sandhurst Manifesto.[164] Emphasizing pragmatism and compromise, he sought to avoid the errors of the reign of Isabella II, particularly the exclusive alignment of the Crown with one liberal faction (the Moderates), which had led others (Progressives) to resort to military uprisings to gain power. Cánovas aimed to allow peaceful alternation between liberal factions, thereby removing the military from political life and restoring civilian leadership.[165][166] Cánovas had the full support of King Alfonso XII, who expressed to the British ambassador his desire to introduce a constitutional system similar to that of Britain. Cánovas, in turn, valued the monarch’s commitment and character.[165][167][168]

The main challenge to Cánovas’ project came not from the left, but from the Moderate Party, described by the British ambassador as "the reactionary section of the Alfonsino party".[169][163][170][171][172] Although his ultimate goal was to divide and integrate them into his system,[173][174][175] Cánovas initially made concessions. The early actions of his government involved revising legislation from the Sexenio Democrático and fostering a negative perception of that period, particularly the First Republic.[176][177]

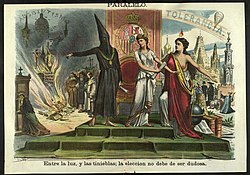

His alignment with the Moderates was most evident in three areas: Church relations, fundamental rights, and academic freedom. The Concordat of 1851 was restored, re-establishing state funding for the Church and repealing laws from the Sexenio, including the legalization of civil marriage—replacing it with obligatory canonical marriage.[163][177][178][179][180][181] Some Protestant temples, newspapers, and schools were closed, and anti-non-Catholic rhetoric was tolerated. Efforts were also made to restore relations with the Holy See and return Church property.[180]

Civil liberties were significantly restricted during Cánovas' first years, a period often referred to as the "dictatorship of Cánovas." Freedom of expression, assembly, and association were curtailed, and opposition newspapers—especially republican ones—were closed or subjected to prior censorship.[162][182][183][184][185][186] A 1875 decree limited press freedom by banning attacks, even indirect or symbolic, on the monarchy. The jury system was suspended.[187][188] In 1879, a restrictive press law criminalized questioning the legitimacy of elections or promoting anti-monarchical views. A 1880 law on assembly further limited political freedoms, distinguishing between legal and illegal political groups.[189][190] Additionally, the 1876 law centralized local government by placing mayoral appointments in large cities under the authority of the king and requiring provincial governors' approval for municipal budgets.[191]

In the field of academic freedom, the Orovio Decree—issued in February 1875 by Minister of Public Works Manuel Orovio Echagüe—prohibited university professors from teaching doctrines contrary to Catholic orthodoxy and the constitutional monarchy, triggering the "second university question".[163][192][193][194] In a circular to university rectors, Orovio urged them to prevent the teaching of ideas opposing Catholic dogma and warned that professors who rejected the established regime would face sanctions.[192][195] The first conflict arose at the University of Santiago de Compostela, where professors Laureano Calderón and Augusto González de Linares were dismissed and imprisoned for presenting Darwinist ideas. This prompted a wave of solidarity among academics, including Francisco Giner de los Ríos, Gumersindo de Azcárate, and Nicolás Salmerón. Many resigned or were expelled and later founded the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, in 1876, which would have a lasting influence on Spanish intellectual life.[196][197][198]

Historians such as José Varela Ortega and Feliciano Montero interpret the decree as a manifestation of internal tensions within Canovism, specifically between its Moderate and September-origin factions.[199] The decree, they argue, was a strategy by the Moderates to resist the broader, more inclusive vision of Cánovas. Though Cánovas considered the measure excessive—and so did the king—he initially tolerated it to maintain political cohesion.[200][201][163][202] At the first opportunity, he dismissed Orovio and appointed Cristóbal Martín de Herrera, who reversed the decree. However, the dismissed professors did not regain their positions until the Liberals came to power in 1881.[163][203] Meanwhile, the Institución Libre de Enseñanza was allowed to operate without interference.[200][204][201]

According to Manuel Suárez Cortina, Cánovas allowed the decree as part of a broader effort to integrate the Moderates into the new regime. This included restoring the Concordat of 1851, reinstating state funding for the Church, and reestablishing canonical marriage.[197] Carlos Seco Serrano adds that such gestures aimed to ideologically neutralize the Carlist threat during an ongoing civil conflict.[205] Years later, in Parliament, Cánovas defended his actions as necessary in the context of war, responding to criticism from Nicolás Salmerón by emphasizing the importance of preserving national unity and religious cohesion during the Carlist uprising.[206]

Despite these concessions, Cánovas resisted three core demands of the Moderates—with the full support of Alfonso XII:[207][208] the reestablishment of the Spanish Constitution of 1845, the restoration of Catholic unity (including the prohibition of non-Catholic worship and the Church’s monopoly over education and civil matters), and the return of Queen Isabella II from exile.[209] While he allowed the return of Princess Isabel (La Chata) and General Serrano, he opposed Isabella II's return. General Martínez Campos even threatened a second pronunciamiento over these issues, and only royal intervention and a posting to Cuba dissuaded him.[200][210][211][212][213][214] Nonetheless, other generals, such as the Counts of Cheste and Valmaseda, continued to pressure for Isabella's return.[213][215]

The Moderates launched a significant campaign demanding the restoration of Catholic unity, arguing that a Catholic nation should not grant equal rights to non-Catholic religions. Petitions collected in support of this demand were delivered to the government in wagons.[216][217] The Holy See, supported by Spanish bishops and conservative sectors of society, also pressed for the return to religious exclusivity, threatening to withhold the appointment of a new nuncio.[218][213][219][220] Some figures, including members of Madrid’s elite, even threatened to support the Carlist pretender if Protestant worship were tolerated.[221] Despite this pressure, Cánovas firmly rejected the reestablishment of Catholic unity, considering it incompatible with the long-term viability of the monarchy. He argued that religious tolerance was essential to gain the support of former revolutionaries and to reassure European powers that the Restoration was not a reactionary regime.[222][223] King Alfonso XII supported this stance, resisting intense lobbying by Moderate politicians, high clergy, nobility, and even his sister, the Princess of Asturias.[218] In response to a bishop, the king stated that although he was a Catholic monarch, he would defend religious freedom in his realm, reflecting Europe’s broader commitment to tolerance.[224][225]

As for ex-Queen Isabella II, Cánovas opposed her return to Spain, fearing it would be seen as a symbol of past regimes and provoke political instability. In an April 1875 letter, he explained that her presence could rekindle old grievances and create division. Even her son advised her against returning, asserting that no one could impose their will on the king.[226][227][228][229]

Isabella was only allowed back after the 1876 Constitution was approved, and even then, her stays were restricted and discreet.[230][231][232] She was excluded from state matters, including her son's marriage to her niece, María de las Mercedes de Orleans, a union she opposed but was barred from publicly denouncing.[233][234] She did not attend the wedding and returned to Paris, where she lived until her death in 1904, with only occasional visits to Spain.[235]

Cánovas' resolve to draft a new Constitution became evident in May 1875, when former parliamentarians of the Elizabethan and Amadeist monarchies were called to form a commission of notables. This move prompted many Moderates to join Canovism and receive government positions, marking the beginning of the Liberal-Conservative Party.[236] The decisive blow to the Moderate Party came during the general elections of January 1876, when Interior Minister Francisco Romero Robledo limited them to just 12 seats, compared to 333 won by Canovists. The Moderate Party was formally dissolved seven years later.[163][237][238] According to historians Feliciano Montero and Fidel Gómez Ochoa, Cánovas' refusal to restore Catholic unity was key to the decline of the Moderates and the consolidation of his Liberal-Conservative Party.[239] Gómez Ochoa also notes that the decision to hold the first elections by universal suffrage further alienated the Moderates, some of whom claimed it undermined the king's legitimacy.[240]

Constitution of 1876

[edit]Elaboration and approval of the Constitution

[edit]

In response to the Moderate Party's demand to restore the Constitution of 1845, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo insisted on drafting a new constitution. To this end, he secured the support of the centrist faction of the Constitutional Party, led by Manuel Alonso Martínez, who formed the Parliamentary Center.[143][241][242][243][244] On May 20, 1875, an Assembly of Notables convened, composed of 341 former deputies and monarchist senators from the Elizabethan era and theSexenio.[182][239][245] Alonso Martínez set the terms: the legitimacy of Alfonso XII’s monarchy could not be questioned, and the goal was to establish constitutional foundations to consolidate the regime.[239]

Although Moderates dominated the Assembly, Cánovas ensured that a 39-member commission—equally composed of Moderates, Canovists, and Centrists—was tasked with drafting the constitutional bases. A nine-member subcommission, including Alonso Martínez, prepared the draft. The main point of contention was the issue of Catholic unity, which was ultimately excluded from Article 11.[241][242][246][247][248] In response, the Moderates issued a public manifesto on August 3, calling for Catholic protest. Around the Canovist faction, which absorbed many former Moderates, the Liberal-Conservative Party began to take shape, with some historians identifying its formal origin in the Assembly of Notables.[182][249][250]

Following this, the government called for elections. A debate arose within the Council of Ministers over whether to retain universal male suffrage, as established by the Electoral Law of 1869. At Cánovas’s proposal, it was decided to hold the elections by universal suffrage “for this one time only,” as a concession to the Constitutionalists. This decision angered the Moderates.[251][252][253][254] To maintain consistency with his personal opposition to universal suffrage, Cánovas resigned, also using the occasion to remove three conservative ministers, including the Marquis of Orovio. General Joaquín Jovellar was appointed head of the government during the electoral preparations, though Cánovas continued to direct policy informally.[255][256] Cánovas remained opposed to universal suffrage. When it was permanently established in 1890 under Sagasta's Liberal government, he warned that its true implementation would lead to “the triumph of communism and the ruin of the principle of property".[257]

Ahead of the elections, held from January 20 to 24, 1876,[258] the Catholic Church campaigned against candidates supporting religious tolerance, labeling it “freedom of perdition".[259] In contrast, the Commission of Notables issued a manifesto defending the proposed constitutional framework as a means to secure public order, protect monarchy, and uphold the advances of the modern liberal state.[260][261]

As a result of the electoral maneuvers of Interior Minister Francisco Romero Robledo,[262] the general elections of January 1876 resulted in a sweeping victory for the Canovist faction,[263] which secured 333 of 391 seats in the Congress of Deputies.[264] Official figures indicated abstention rates exceeding 45% overall, and up to 65% in major cities.[258][264][265] The Moderate Party won only twelve seats, marking its political collapse.[266][197][267] Many of its former members subsequently joined Cánovas's Liberal-Conservative Party. The final blow came when Cánovas raised a cabinet question during the debate on Article 11 of the Constitution, forcing the Moderates to take a public stance against its failure to restore Catholic unity. The Moderate Party formally dissolved in 1882, with its full absorption into the Liberal Conservative Party completed in 1884, when the Catholic Union, founded by Alejandro Pidal, joined the party. [268]

In contrast, Sagasta's Constitutionalists were granted 27 seats as part of a prior agreement.[258][269] This included a seat for Sagasta himself in Zamora, which he would hold almost continuously. In November 1875, the Constitutionalists had declared their intention to support the monarchy as "the most liberal party of the Government within the constitutional Monarchy of Alfonso XII".[270][271]

The new Cortes, criticized as Las Cortes de los Milagros due to widespread allegations of electoral fraud,[272] convened on February 15, 1876. Debate on the Constitution was limited, with key provisions—especially those related to the powers of the Crown—excluded from discussion at Cánovas’s request.[273] The Constitution was approved on May 24 in the Congress (by 276 votes to 40) and on June 22 in the Senate (by 130 to 11).[274][275][276][277]

The 1876 Constitution, a concise document of 89 articles and one additional article,[278] represented a synthesis of the Constitutions of 1845 and 1869, though it leaned heavily toward the former.[279] It reaffirmed shared sovereignty between the king and the Cortes, abandoning the principle of national sovereignty espoused in 1869.[241][280][281][282][283][284] While it retained a broad declaration of individual rights, it allowed these rights to be restricted or suspended by ordinary legislation.[241][280][281][282][285][286]

Ambiguities were deliberately left in key areas to enable both Conservatives and Liberals to govern according to their principles without needing constitutional reform.[241][280][281][282][285][286] For example, the issue of suffrage was delegated to future electoral laws. The Electoral Law of 1878 restored restricted suffrage, limiting the vote to about 850,000 men, while the 1890 law, enacted under Sagasta, introduced universal male suffrage, expanding the electorate to approximately 4.5–5 million.[189][287][288][289][290] Nonetheless, electoral fraud remained systemic, as governments were formed prior to elections and routinely secured overwhelming majorities.[291][292]

The most contentious issue was the religious question.[293] The Constitution abolished the freedom of public worship recognized in 1869 but did not reinstate the Catholic unity sought by the Moderates.[241][267][278][294] Cánovas personally drafted Article 11, which preserved the confessional character of the state while allowing private worship for other religions.[267][278][295]

Art. 11. The Catholic, Apostolic, Roman Religion is that of the State. The Nation is obliged to maintain the cult and its ministers. No one shall be disturbed in Spanish territory for their religious opinions or for the exercise of their respective worship, except for the respect due to Christian morality. However, no ceremonies or public manifestations other than those of the State religion shall be permitted.

Despite initial resistance, the Catholic Church accepted this arrangement, confident that future laws would protect its position. This was later confirmed by the Spanish Cardinal Primate, who acknowledged that Article 11 had safeguarded Catholic interests more effectively than a prohibitive clause would have.[267]

Powers of the King: "la regia prerrogativa"

[edit]

For the drafters of the 1876 Constitution, led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the Monarchy was not merely a form of government but the foundational pillar of the Spanish State. Cánovas proposed to the Commission of Notables that the titles and articles referring to the Monarchy be excluded from parliamentary debate, placing it above both ordinary and constitutional legislation.[296][297] In his view, the Monarchy embodied sovereignty, legality, and continuity, standing above partisan conflicts.[298]

Cánovas believed that both during Isabella II’s reign and the Sexenio Democrático, it was not public opinion that determined who governed, but rather the governments that created the necessary parliamentary majorities through control of the electoral process. "Here the government has been the great corrupter," he stated, lamenting the lack of independence and initiative in the electorate. This view was shared by other political figures, such as Manuel Alonso Martínez, who criticized the imbalance between voters and the government, and Sagasta’s constitutionalists, whose newspaper La Iberia acknowledged the entrenched electoral manipulation.[299][300]

To guarantee the alternation of liberal factions in power, Cánovas assigned a key role to the Crown as a "moderating power".[301] In practice, it was the monarch—not electoral outcomes—who decided changes in government based on perceived shifts in public opinion. Governments were formed before elections, and the Ministry of the Interior, which controlled the electoral machinery, ensured their victory.[302][303] This process, known as encasillado, involved negotiating electoral outcomes in advance among political elites. Historian José María Jover noted that the king appointed a prime minister, who then received royal authorization to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections. These elections consistently produced majorities favorable to the government in power.[304]

Carlos Dardé described this royal prerogative—the ability to form a government and call elections—as the "practical exercise of sovereignty," making the monarch the central figure in the system.[5] British ambassador Robert Morier summarized the situation in 1882: "The final decision regarding the political destinies of the nation does not rest in the electoral districts [...] but in another place not defined in the Constitution. He pointed out that while parliamentary majorities were formally required, they were achieved through manipulation directed by the Interior Ministry, with the Crown controlling access to this apparatus.[305][306]

However, the monarch’s role as "moderating power" was not without complications. Ramón Villares likened the king’s position to that of a "pilot without a compass," possessing great authority but lacking reliable instruments to exercise it effectively.[307] Jover, following José Varela Ortega, posed the same dilemma: without genuine electoral indicators, the monarch based decisions on a leader’s ability to maintain party unity and dominate their respective faction within the bipartisan system established by the Restoration.[308]

The principle of shared sovereignty between the King and the Cortes, enshrined in Article 18 of the 1876 Constitution ("the power to make laws resides in the Cortes with the King"),[309] provided the legal foundation for the Crown’s role in distributing political power. This granted the monarchy a personal and extraordinary—though not absolute—authority, justified, according to Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, by the absence of an electorate independent from government influence. "The Monarchy among us has to be a real and effective, decisive, moderating and directing force, because there is no other in the country," Cánovas affirmed. His close ally Manuel Alonso Martínez echoed this, stating that the monarchy had to assume functions that, in a fully representative regime, would be carried out by the electoral body.[298][310] As historian Ramón Villares noted, the monarch held "all the keys to the political system of the Restoration," and governments required the "double confidence" of both the Cortes and the King.[307] According to Article 49, no royal decree could be enacted without a minister’s endorsement; in cases of disagreement, the king either had to dismiss the government or yield to its stance.[296]

The monarchy thus became the axis of the Restoration regime. The "royal prerogative" referred to the Crown’s power to arbitrate political life, a long-standing goal of Cánovas: to establish a monarchy that was real, effective, and stabilizing in the absence of a mature electorate.[298] However, Suárez Cortina emphasized that this came at the cost of systematic electoral fraud. Political life became a fiction, where the will of the voters was replaced by that of the monarch. The arrangement provided stability, but it was disconnected from the national will and served the interests of the conservative bourgeoisie following the upheaval of the democratic Sexenio".[311]

Carlos Dardé concurred, noting that placing the distribution of power in royal hands rendered pronunciamientos obsolete and discouraged genuine electoral competition. While party rivalry was not eliminated—the king had to consider their social bases—it was weakened, delaying broader political engagement. This reinforced clientelism, where access to state resources depended more on loyalty and connections than on merit or policy. With the judiciary also under political influence, corruption flourished unchecked, as Joaquín Romero Maura observed, "with no brake but individual morality." Even the king admitted in private that his goal to "moralize the Spanish public administration" had failed and that this failure was met with widespread indifference.[312]

As José María Jover emphasized, any analysis of the 1876 Constitution must begin with the recognition that the political dynamics outlined in its text—particularly the role of the electorate and parliamentary majorities in forming or dismissing governments—were never intended to function in practice. The system’s architects anticipated a gap between formal provisions and political reality.[313] This duality, between the formal constitution and the actual operation of political life,[314] allowed parties to implement their programs from positions of power while using public funds and administrative appointments to reward loyal supporters—often driven as much by material gain as by ideology.[315]

End of the Carlist war: the "soldier King"

[edit]

One of the main priorities of Cánovas del Castillo's conservative government was to end the two ongoing conflicts: the war in Cuba and the Third Carlist War. Politically, the government aimed to erode the Carlists' support among Catholic sectors and the clergy. To this end, it revised the anti-religious measures enacted during the Sexenio Democrático, and in May 1875, lodged a complaint with the Vatican over its perceived lack of cooperation and tacit support for a rebellious clergy. A notable achievement was convincing former Carlist general Ramón Cabrera, then in London, to recognize Alfonso XII and denounce Catholic divisions. In response, the Carlist pretender Carlos VII stripped Cabrera of his honors and titles.[316][317] According to Carlos Seco Serrano, Cabrera’s change of allegiance stemmed largely from his favorable impression of Prince Alfonso during a visit to Sandhurst. In return, Cabrera was granted the rank of captain general and noble titles.[318]

Militarily, the first campaign, led by War Minister General Jovellar,targeted the Carlist "center" zone—covering parts of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, and Castile—where guerrilla forces were active. After the fall of key strongholds such as Miravet and Cantavieja June 1875, General Dorregaray's forces were forced to retreat to the Basque provinces, a move some Carlists saw as betrayal. With the central front neutralized, the army turned to Catalonia, where General Martínez Campos captured La Seu d'Urgell in August after a prolonged siege, consolidating control over the region. The final campaign focused on the Carlist stronghold in the Basque Country and Navarre, where a proto-state and regular army had been established. A coordinated pincer movement from Navarre and Biscay culminated in the capture of Estella on February 19, 1876, following the decisive Battle of Montejurra led by General Fernando Primo de Rivera. Carlos VII fled to France by the end of the month.[319][320][321][322][323]

Cánovas ensured that Alfonso XII assumed personal command of the northern campaign, reinforcing his image as a “soldier-king.” The king entered San Sebastián and Pamplona at the head of his troops, coinciding with Carlos VII’s departure from Spain.[324][325] In his victory proclamation, Alfonso XII embraced this role:[325][326]

I will never forget your deeds; do not forget, on the other hand, that you will always find me ready to leave the Palace of my elders to occupy a tent in your camps; to place myself in front of you and that in the service of the fatherland I will run, if necessary, mixed with yours, the blood of your King.

In the "Somorrostro Proclamation" of March 3, the king called for reconciliation: "No one should be humiliated by his defeat; in the end, the victor's brother is the vanquished".[327] Upon his return to Madrid, Alfonso XII was received with popular acclaim and hailed as "The Peacemaker".[327][328]

The monarch’s military role—unusual in 19th-century Spain outside Carlism—[253]was formally codified in the 1876 Constitution: Article 52 granted the king supreme command of the armed forces, and Article 53 authorized him to confer military ranks and rewards.[329] The 1878 Constitutive Law of the Army further reinforced this by allowing the king to command personally without requiring ministerial countersignature and by giving him decisive influence over military appointments.[189][253][329]

According to Cánovas, these powers were designed not to militarize the monarchy but to “civilize” Spanish political life by removing the army from active politics and preventing military interventionism. This goal was largely achieved, as seen in the limited scope and failure of the few republican uprisings that followed.[189][330][331] Alfonso XII later credited himself with the success of excluding the military from public life.[332]

"Abolition of the Basque fueros"

[edit]Following the defeat of the Carlists, Cánovas del Castillo addressed the long-standing issue of integrating the Basque provinces into the constitutional framework of the monarchy. This matter had remained unresolved since the 1839 Law of Confirmation of Fueros,[333][334] passed after the end of the First Carlist War. While Navarre had reached an agreement with the central government through the 1841 Ley Paccionada,[335][336] the Basque provinces—Álava, Gipuzkoa, and Biscay—had retained more foral (regional) privileges,[337] despite a 1844 royal decree that introduced some centralizing reforms.[338]

In April 1876, Cánovas summoned representatives from the three provinces to discuss the implementation of the 1839 law, but no consensus was reached.[339][340] As a result, the government pushed through the Law of July 21, 1876, which the Basque authorities labeled the “abolitory law” and refused to apply.[335][341] While the law did not dismantle the fueros entirely—it maintained the Juntas and Diputaciones—it abolished the key exemptions that contradicted constitutional unity, particularly regarding military conscription and taxation. Article 1 of the law stated:[342][343]

The duties that the political Constitution has always imposed on all Spaniards to go to the military service when the law calls them, and to contribute, in proportion to their assets, to the expenses of the State, will be extended, as the constitutional rights are extended, to the inhabitants of the provinces of Biscay, Gipuzkoa and Alava, in the same way as to all the rest of the nation.

The law sparked widespread outrage. While local institutions were not formally dissolved, their leaders denounced the measure as a violation of their traditional rights and liberties.[345] According to historian Luis Castells, Cánovas did not aim to eliminate the entire foral system, but sought to enforce constitutional uniformity in military and fiscal matters, drawing inspiration from Navarre’s 1841 model.[346] Ironically, years earlier, Cánovas had praised Basque institutions in a book prologue.[347]

The Basque authorities publicly refused to cooperate, triggering a two-year standoff. For example, in early 1877, efforts to implement conscription were obstructed, and anti-law publications were censored.[348] Over time, moderate (“transigent”) factions gained influence in Gipuzkoa and Álava, favoring negotiation with Madrid. In contrast, Biscay, led by General Deputy Fidel Sagarmínaga, remained staunchly opposed.[349]

In May 1877, the government dissolved the Biscayan Diputación, replacing it with a standard provincial council. Six months later, the same was done in Gipuzkoa and Álava after continued resistance.[344] Castells notes that only at this point could one speak of a real abolition of the fueros, although their legacy endured.[350]

With moderate leaders now in control, negotiations resumed,[347] culminating in the Royal Decree of February 28, 1878, which incorporated the three provinces into Spain’s "economic agreement" system. Under this arrangement—similar to Navarre’s—the provincial councils would collect taxes and remit an agreed quota to the State.[335][347][351][352] Historian Feliciano Montero described this concierto económico as a pragmatic compromise that initially met little resistance but left a lingering sense of grievance that would later fuel Basque nationalism.[342]

The agreement was especially well-received by the Basque bourgeoisie, particularly in Biscay, where industrialization was accelerating. As José Luis de la Granja points out, the system relied mainly on indirect taxes and imposed few direct levies, making it economically favorable.[347] Castells adds that while political autonomy was curtailed, the provinces retained significant administrative and fiscal autonomy under the concierto system, resulting in a comparatively lighter tax burden—something Cánovas himself acknowledged.[353] In the 1879 general elections, the transigents triumphed. From that point, the Basque provinces were integrated into the Restoration Monarchy—without their fueros, but with the conciertos. This provided substantial economic and administrative autonomy, though not political self-governance.[347]

Religious policy: the application of Article 11 of the Constitution

[edit]Following the approval of the 1876 Constitution—opposed by Catholic sectors for not recognizing Catholic unity—the debate shifted to the application of Article 11. This article granted limited religious tolerance, restricted to the private sphere: "No one shall be disturbed in Spanish territory for their religious opinions or the exercise of their respective worship, except for the respect due to Christian morality. However, no ceremonies or public manifestations other than those of the State religion will be allowed". To reassure the Catholic hierarchy, Prime Minister Cánovas issued a circular on October 23, 1876, instructing civil governors to interpret Article 11 restrictively.[354] Public acts by non-Catholic groups, including ceremonies visible in streets or on temple exteriors, were deemed prohibited. The opening of dissenting temples or schools had to be reported to local authorities, and schools were to operate separately from places of worship. These guidelines were contested by more liberal cabinet members, such as Manuel Alonso Martínez and José Luis Albareda, as well as by foreign diplomats, particularly the British ambassador.[355]

A new dispute arose when the government introduced a Public Instruction bill in December 1876. Opposed by the bishops, who were supported by the Vatican, the bill was withdrawn and postponed until 1885. The hierarchy objected to the establishment of compulsory primary education, which they saw as a move toward state monopoly over education, diminishing the Church’s role. The bill also subordinated episcopal oversight of educational content—recognized in the still-valid Concordat of 1851—to state inspection.[356] In 1885, during Cánovas's second term, Public Works Minister Alejandro Pidal y Mon issued a decree favoring private religious education, which subsequently expanded significantly.[356]

Another conflict centered on canonical marriage. A decree in February 1875 restored full civil recognition to religious marriages, reversing the 1870 law from the Democratic Sexennium. Tensions resurfaced in 1880 with a new bill on the civil effects of marriage, which the Church rejected for allowing state regulation of a sacrament. After prolonged negotiations, the Holy See in 1887 acknowledged the state's authority to regulate civil aspects of religious marriage. This agreement was incorporated into the Civil Code of 1889.[357]

Cánovas also sought Vatican support in marginalizing fundamentalist Catholics who rejected the restored monarchy due to its failure to uphold Catholic unity. Many of these were bishops aligned with traditionalist-Carlist positions. The accession of Pope Leo XIII in 1878 improved relations, as he adopted a more conciliatory stance toward liberal regimes. This shift led to the founding of the Catholic Union in 1881, led by Pidal y Mon and backed by the hierarchy, aiming to unite Carlist and Alfonsist Catholics. However, it remained a minority compared to the traditionalist faction led by Cándido Nocedal, editor of El Siglo Futuro. Tensions peaked during the 1882 pilgrimage to Rome honoring Pius IX, which Nocedal used to discredit the Catholic Union. The Vatican ultimately distanced itself from the initiative. In response, Pope Leo XIII issued the encyclical Cum Multa, addressed to Spanish Catholics, urging them to avoid equating religion with political factions and warning against internal divisions.[358][359] Despite this intervention, the split within Spanish Catholicism persisted.[359]

War in Cuba: the "Peace of Zanjón", the brief government of Martínez Campos (February–December 1879) and the return of Cánovas

[edit]

After the victory in the Third Carlist War, Cánovas's government turned its attention to ending the ongoing conflict in Cuba, which had begun in October 1868 and caused nearly 100,000 deaths—over 90% due to disease.[351][360] Between 42,000[361] and 70,000[362] Spanish troops were sent to the island to confront about 7,000 insurgents, and a loan of 200 million pesetas was secured from the newly established Banco Hispano Colonial to finance the campaign.[363][364] General Martinez Campos, appointed to lead military operations, arrived in November 1876. He implemented more humane policies aimed at reducing popular support for the insurgency, particularly among rural populations, and took advantage of growing divisions within the rebel ranks.[351][362][365][366]

In late 1877, Martínez Campos opened negotiations with the rebels, culminating in the signing of the Zanjón Agreement on February 10, 1878. It granted Cuba the same political and administrative status as Puerto Rico".[365][367][368][369][370] The "peace of Zanjón" was widely seen as a turning point, marking the beginning of a new era of formal liberties for Cubans.[371][372] However, some planters and slave owners opposed the agreement, believing too many concessions had been made to the rebels; one critic called it "the thousand times cursed peace of Zanjón".[373]

The end of the Cuban war was overshadowed by the illness and death of Queen Maria de las Mercedes of Orleans. Diagnosed with "essential toxic fever" (a euphemism forword typhus), she died on June 26, 1878, two days after her 18th birthday and just five months after her marriage to Alfonso XII.[374][375][376][377] Four months later, on October 23, the king survived an assassination attempt on Madrid’s Calle Mayor. The assailant, Juan Oliva Moncusí, a self-declared member of the International Workingmen’s Association, was arrested and executed on January 4, 1879.[378] In response, Cánovas accelerated plans for the king’s remarriage to secure dynastic continuity. Alfonso XII accepted, leaving the choice to Cánovas, who selected Archduchess Maria Christina of Habsburg-Lorraine, a 21-year-old Catholic and niece of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria.[379][380] The wedding took place on November 29, 1879, at the Basilica of Atocha, attended by former Queen Isabella II.[381][382]

Martínez Campos returned to Spain in early 1879, convinced that only political and economic reforms could prevent future uprisings in Cuba.[383] On March 7, he became Prime Minister, due to both his prestige and the difficulties Cánovas faced in implementing parts of the Zanjón Agreement, which he did not fully support.[384][385][386][387] Although Sagasta's constitutionalists protested at being excluded from power, their party was still weak, and key figures like General Serrano had yet to fully accept the restored monarchy, remaining involved in republican efforts.[388] According to José Varela Ortega, Cánovas advised the king to appoint Martínez Campos to counter these "revolutionary threats" with a respected and victorious general.[389][390]

Despite leaving office, Cánovas retained political control, as confirmed by the general elections of April 20 and May 3, 1879. Held under the new Electoral Law of 1878—which restricted suffrage to male citizens over 25 who met economic or educational qualifications—only 847,000 men were eligible to vote. The law also enfranchised certain professionals and public officials, such as clergy, military officers, and high-ranking civil servants.[391] Through electoral manipulation, the Liberal-Conservative Party, led by Cánovas, secured a dominant majority: 293 deputies versus 56 from Sagasta’s Constitutional Party.[392] As a result, Martínez Campos was politically dependent on Cánovas. Following the opening of the new Cortes, the president of the Congress welcomed Cuban representatives—their first seating since their expulsion in 1837—and encouraged their full participation in the affairs of the monarchy.[393][394]

The abolition of slavery in Cuba—where around 200,000 enslaved people remained—was addressed by a bill introduced to the Cortes by Prime Minister Martínez Campos.[395] The proposal included a transitional system known as patronato, under which former slave owners retained limited control over their former slaves for eight years. They were required to pay wages, provide food, clothing, medical care, and primary education for children. Despite its gradual approach, the bill faced strong opposition from plantation owners and their political allies. Debate was postponed until December 5 due to preparations for the king’s wedding on November 29.[396][397]

Martínez Campos's position was further weakened by the outbreak of the Guerra Chiquita in August 1879, a renewed rebellion in Cuba that would last until late 1880,[385][398][399] and by devastating floods in October in Almería, Alicante and Murcia—later known as the Santa Teresa flood. King Alfonso XII’s personal visit to the affected areas earned him public admiration.[400]

After the royal wedding, internal divisions emerged within the government over a proposed tax and tariff reform for Cuba and the slavery abolition bill. Martínez Campos resigned on December 9. Attempts to find an alternative—such as appointing Posada Herrera or Adelardo López de Ayala—failed, and Alfonso XII recalled Cánovas to lead the government.[394][401][402]

To restore party unity, Cánovas adopted the abolition bill, reportedly with the king’s support. Although he introduced modifications favorable to slaveholders—including the retention of corporal punishment, opposed by Sagasta’s constitutionalists—the law was passed in February 1880.[403] The final regulations imposed stricter controls, such as the use of stocks and shackles for “sponsored” slaves who refused to work or left plantations without permission.[385][404][405] The Constitutional Union accepted the modified patronato system in August 1880.[403]

Martínez Campos’s removal led to a rift within the Conservative Party. Many of his supporters, particularly military allies, moved closer to Sagasta’s Constitutionalists, laying the groundwork for the Liberal-Fusionist Party—one of the two pillars of the Restoration regime.[406][407][408] On June 11, 1880, Cánovas and Martínez Campos clashed in a Senate debate. Martínez Campos emphasized the importance of the Sagunto pronunciamiento in restoring the monarchy, while Cánovas dismissed it, arguing that larger political and military forces were decisive.[409][410]

On December 30, 1879, King Alfonso XII and Queen Maria Christina survived a second assassination attempt. The attacker, Francisco Otero González, fired two shots but missed.[411] Shortly afterward, it was announced that the queen was pregnant. Their daughter was born on September 11, 1880.[412]

First liberal government of Sagasta (1881-1883)

[edit]Arrival of the liberals to power

[edit]

Unlike the Conservative Party, which by 1876 was largely consolidated under the leadership of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo—[385][413] though through a difficult and contentious process—[414] the Liberal Party did not take definitive shape until the spring of 1880. At that time, most members of the former Constitutional Party of the Sexenio, following the lead of the "centralists" around Manuel Alonso Martínez,[415]abandoned their support for the 1869 Constitution and severed ties with republican leaders Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla and Emilio Castelar. Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, the Constitutionalists’ leader, was a pragmatic figure similar to Cánovas, believing that "in politics, one cannot always do what one wants, nor is it always convenient to do what is most just".[406][416][417][418][419]

This shift in strategy culminated in the fusion of Sagasta's faction with the dissident conservatives led by General Martínez Campos, who had broken with Cánovas after his brief premiership, as well as the centralists.[406][420][421][422][423][424] The result was the creation, in May 1880, of the Liberal-Fusionist Party under Sagasta's leadership. King Alfonso XII played a behind-the-scenes role in the party's formation.[406][425][420][421][422][426][427][428] According to historian Feliciano Montero, the new party was ideologically diverse and lacked cohesion—an observation echoed by Cánovas and his allies, who were reluctant to relinquish power.[429] Cánovas had previously admitted to the British ambassador that he intended to remain in office as long as possible because, in his view, the liberal opposition was too fragmented to govern effectively.[430]

Sagasta publicly presented the Liberal-Fusionist Party before the Cortes on June 14, 1880, declaring its support for the 1876 Constitution—an essential condition for political legitimacy within the Restoration system. He described the party as committed to the most liberal interpretation of the constitutional framework.[431]

In the same session, deputy Fernando León y Castillo criticized the concentration of power in Cánovas’s hands, accusing him of dominating the Interior Ministry, controlling elections and Parliament, and thereby securing his continued leadership through a self-reinforcing cycle of political dominance.[432]

From its inception, the Liberal-Fusionist Party pressed Alfonso XII to hand over power, warning of possible revolutionary consequences. Historian Carlos Seco Serrano noted that the Conservatives had already governed for five years since the Restoration and that the king was reluctant to dissolve the recently elected Cortes—a step that would have been required had Sagasta been appointed.[433] According to José Varela Ortega, a June 1880 meeting between the king and fusionist leaders ended with the monarch assuring them he would call them to govern once they had formed a viable alternative to the Conservatives.[434] On January 19, 1881, amid a heated parliamentary debate, Sagasta invoked the royal prerogative to demand his right to govern. He warned that without liberal participation, the Restoration regime would lack legitimacy, hinting at potential unrest if their claim to power continued to be denied:[435][436][437]

If my efforts and my sacrifices were sterile because of your obstinacy and your tenacity, I will see it with a sorrowful soul, but with a clear conscience; because whatever the vicissitudes, whatever the destiny we all have prepared, as I must always fall on the side of freedom, I will then say with my forehead raised: I am where I was; neither then did I obey the inspirations of patriotism, nor today do I yield to the impulses of duty and the feelings of the heart.

Shortly after receiving party leaders at the Palace on his birthday (January 23), King Alfonso XII forced Cánovas’s resignation on February 6, 1881, after the latter refused to sign a decree. The king then entrusted the formation of a government to Práxedes Mateo Sagasta. On February 8, the first Liberal cabinet of the Restoration was sworn in.[438] According to Carlos Seco Serrano, Cánovas had provoked the crisis by including in a debt conversion decree a justification that implied the need to extend his government’s mandate.[439] However, historians such as Carlos Dardé and Ángeles Lario argue that the crisis was initiated by the king himself, who had lost confidence in Cánovas and used the decree as a constitutional mechanism to trigger his resignation.[440][441] José Ramón Milán García also points to Alfonso XII’s initiative, noting that the monarch recognized a shift in the liberal opposition: it had distanced itself from revolutionary positions and incorporated loyal dynastic elements.[442] José Varela Ortega supports this view, highlighting the internal divisions among conservatives and the threat of a liberal-republican alliance.[443]

Conservatives emphasized that the Liberals came to power not through a parliamentary victory, but by royal decision. The conservative newspaper La Época wrote that the Liberal-Fusionist Party owed its rise to "the free initiative and will of the King." Conservative leader Romero Robledo acknowledged the loss of power: “We had a majority in the Chambers [...], but a higher wisdom [...] believes that the time has come to change policy".[444][445][446][447] As Dardé noted, the February 1881 crisis confirmed that ultimate political authority rested with the monarch.[448]

The entry of the Liberals into government caused unease among conservative sectors, given the revolutionary past of some leaders, including Sagasta.[449] Nevertheless, their accession marked the beginning of the alternation of power—or turno pacífico—between the Conservatives and Liberals, a defining feature of the Restoration system. According to Feliciano Montero, it ended political exclusivism and signaled the regime’s consolidation.[445][450] Manuel Suárez Cortina emphasized the break from five years of Canovist dominance, while noting that many conservative elites still viewed Sagasta's faction with suspicion.[431] Carlos Dardé observed that the traditional resistance to progressive governance had now dissipated.[451][452]

As José Ramón Milán García summarized, the Liberals’ arrival in power was a key moment in Alfonso XII’s reign. It marked a significant step in overcoming the longstanding division between left-wing liberalism and the Bourbon monarchy, and a move toward reconciling the fragmented currents of Spanish liberalism.[453]

First stage of Sagasta's government (1881-1882)

[edit]

1881, reflected the diverse composition of the Liberal-Fusionist Party. It included representatives of the constitutionalists, the centralists led by Manuel Alonso Martínez, and the group of former conservatives aligned with General Martínez Campos. José Posada Herrera, also from the conservative camp, became president of the Congress of Deputies.[445][454][455] Within the party, the constitutionalists represented the left and upheld the principle of national sovereignty, while the centralists and campistas formed the right wing, advocating for "shared sovereignty".[456][457] These internal differences soon became evident, particularly in disputes over the distribution of administrative posts and positions in municipal and general elections.[445][458]

Sagasta had to balance these factions while managing the party’s extensive clientelist networks,[445][458] typical of 19th-century Spanish politics. As Feliciano Montero noted, these networks relied less on ideology than on the ability to grant favors through discretionary and often fraudulent use of administrative power.[459][460] Sagasta understood that maintaining party unity was crucial—both for preserving his leadership and because the king’s support was contingent upon it.[461]

The government’s early actions signaled a shift toward greater public freedoms,[452][462][463] reviving many liberal principles from the Revolution of 1868 and reversing aspects of the Restoration that had been seen as reactionary.[464][465] Public demonstrations and political banquets were authorized for the anniversary of the 1873 Republic, and a royal decree lifted the suspension of several newspapers, dismissed pending cases, and announced a forthcoming press law. A circular from Justice Minister Manuel Alonso Martínez ended prior censorship of political issues, and another from Public Works Minister José Luis Albareda repealed the 1875 Orovio Decree, allowing dismissed university professors such as Emilio Castelar, Eugenio Montero Ríos, Segismundo Moret, Nicolás Salmerón, Gumersindo de Azcárate, and Francisco Giner de los Ríos to return to their posts.[463][466][467][468]

These liberalizations revitalized political life. Public demonstrations, republican and secular propaganda, and opposition discourse flourished under the new freedoms. Emilio Castelar praised the government for restoring liberty, ending press censorship, reopening universities to all schools of thought, and enabling democratic expression.[469][467][465]

The 1881 general elections, managed by Interior Minister Venancio González, resulted in a sweeping victory for the Liberal-Fusionist Party. In candidate selection, Sagasta favored centralists and former conservatives over constitutionalists to strengthen party cohesion.[470] This centrist, pragmatic line also shaped his legislative agenda, aimed at showing that liberal parties could govern stably and responsibly. Sagasta emphasized gradual reform to ensure longevity similar to that of the Conservatives.[471][472]