インターフェロンγ

| Interferon gamma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

生物学的活性を持つヒトIFN-γ一本鎖変異体の結晶構造 | |||||||||

| 識別子 | |||||||||

| 略号 | IFN gamma | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00714 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0053 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002069 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1rfb | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1rfb | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| IUPAC命名法による物質名 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 臨床データ | |

| 販売名 | Actimmune |

| Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601152 |

| 識別 | |

| CAS番号 | 98059-61-1 |

| ATCコード | L03AB03 (WHO) |

| DrugBank | DB00033 |

| ChemSpider | none |

| UNII | 21K6M2I7AG |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201564 |

| 化学的データ | |

| 化学式 | C761H1206N214O225S6 |

| 分子量 | 17,145.65 g·mol−1 |

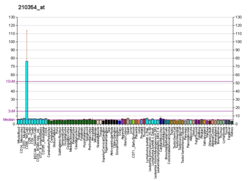

インターフェロンγ(英: interferon gamma、略称: IFN-γ)は、二量体型可溶性サイトカインであり、II型インターフェロンの唯一のメンバーである[5]。このインターフェロンは当初は免疫インターフェロン(immune interferon)と呼ばれており、E. F. Wheelockによってフィトヘマグルチニン刺激を受けたヒト白血球による産物として記載された[6]。また抗原刺激されたヒトリンパ球[7]やツベルクリン感作マウス腹膜リンパ球[8]でも産生されることが示され、水疱性口内炎ウイルスの増殖を阻害することが示された。こうした報告には、現在結核の検査に広く用いられているIFN-γ遊離試験の基礎をなす観察が含まれていた。ヒトでは、IFN-γタンパク質はIFNG遺伝子によってコードされる[9][10]。

機能[編集]

IFN-γ(II型インターフェロン)は、ウイルス、一部の細菌、原生動物の感染に対する自然免疫と獲得免疫に重要なサイトカインである。IFN-γはマクロファージの重要な活性化因子であり、MHCクラスII分子(MHC II)の発現の誘導因子でもある。IFN-γの発現の異常は、多数の自己炎症・自己免疫疾患と関係している。免疫系におけるIFN-γの重要性はウイルスの複製を直接阻害することもその1つであるが、最も重要なのは免疫を刺激し調節する効果である。IFN-γは自然免疫応答の一部として主にNK細胞とNKT細胞によって産生され、抗原特異的免疫の誘導後はCD4+Th1細胞、CD8+細胞傷害性T細胞(CTL)エフェクターT細胞によって産生される[10][11]。IFN-γは非細胞傷害性の自然リンパ球(ILC)によっても産生される[12]。

構造[編集]

IFN-γ単量体は、6本のαヘリックスからなるコアとC末端領域のフォールディングしていない配列から構成される[13][14]。生化学的活性を有する二量体は、2つの単量体が逆向きに互いにかみ合うように結合することで形成される。

受容体への結合[編集]

IFN-γに対する細胞応答は、IFNGR1とIFNGR2からなるヘテロ二量体型受容体との相互作用を介して活性化される。受容体へのIFN-γの結合は、JAK-STAT経路を活性化する。JAK-STAT経路は、MHC IIなどのインターフェロン誘導遺伝子のアップレギュレーションを誘導する[15]。IFN-γは細胞表面のヘパラン硫酸にも結合する。他のヘパラン硫酸結合タンパク質の多くが結合によって生物学的活性が促進されるのとは対照的に、IFN-γのヘパラン硫酸への結合はその生物学的活性を阻害する[16]。

上で示されている構造モデル[14]は全て、全長143アミノ酸からなるIFN-γのC末端の17アミノ酸が削られたものである。ヘパラン硫酸に対する親和性は、この削られた17アミノ酸の配列内によって担われている[17]。この17アミノ酸配列内にはD1、D2と名付けられた2つの塩基性アミノ酸クラスターが存在し、ヘパラン硫酸は双方のクラスターと相互作用する[18]。ヘパラン硫酸が存在しない場合、D1配列はIFN-γ/受容体複合体の形成率を増加させる[16]。

ヘパラン硫酸とIFN-γとの相互作用の生物学的重要性は明らかではないが、D1クラスターのヘパラン硫酸の結合は、IFN-γをタンパク質分解から保護している可能性がある[18]。

生物学的活性[編集]

IFN-γはヘルパーT細胞(より具体的にはTh1細胞)、細胞傷害性T細胞、マクロファージ、粘膜上皮細胞、NK細胞によって分泌される。IFN-γは初期自然免疫応答におけるプロフェッショナル抗原提示細胞の重要な自己分泌シグナルであるとともに、獲得免疫応答における重要な傍分泌シグナルでもある。IFN-γの発現はサイトカインIL-12、IL-15、IL-18、そしてI型インターフェロンによって誘導される[19]。IFN-γは唯一のII型インターフェロンであり、I型インターフェロンとは血清学的に異なる。IFN-γは酸に不安定であるが、I型インターフェロンは安定である。

IFN-γは抗ウイルス、免疫調節、抗腫瘍作用を持つ[20]。IFN-γは最大30種類の遺伝子の転写を変化させ、NK細胞活性の促進[21]、二次性細菌感染に対する肺胞マクロファージのプライミング[22][23]など、生理学・細胞レベルでさまざまな応答を引き起こす。

IFN-γは、Th1細胞を特徴づける主要なサイトカインである。Th1細胞はIFN-γを分泌し、より多くの未分化CD4+細胞(Th0細胞)をTh1細胞へ分化させ[24]、ポジティブフィードバックを形成する一方でTh2細胞への分化を抑制する。

妊娠中の活性[編集]

マウスでは、子宮ナチュラルキラー細胞はIFN-γなどの化学誘引物質を高レベルで分泌する。IFN-γは母体のらせん動脈を拡張して血管壁を薄くし、着床部位への血流を増加させる。このリモデリングは、胎盤が栄養素を求めて子宮へ進入する際にその発生を補助する。IFN-γノックアウトマウスでは妊娠による脱落膜動脈の正常な変化の開始が起こらない。こうしたモデルマウスでは脱落膜の細胞数の異常な減少または壊死がみられる[25]。

ヒトでは、高レベルのIFN-γは流産のリスクの増加と関係している。相関研究では、自然流産歴のある女性では、流産歴のない女性と比較して高レベルのIFN-γが観察されている[26]。IFN-γには栄養芽層に対する細胞毒性がある可能性があり、それによって流産が引き起こされている可能性がある[27]。しかしながら、IFN-γと流産との関係に関する因果研究は倫理的問題のため行われていない。

生産[編集]

ヒト組換えIFN-γは高価な生物学的製剤であり、原核生物、原生動物、菌類(酵母)、植物、昆虫や哺乳類細胞などさまざまな発現系で発現が行われている。ヒトIFN-γは大腸菌Escherichia coliでの発現が一般的であり、ACTIMMUNEの名称で市販されている。しかしながら、原核生物発現系由来の産物は糖鎖修飾が行われておらず、注入後の血流中での半減期が短い。また、細菌発現系からの精製過程も非常に高コストである。ピキア酵母Pichia pastorisなど他の発現系は、収量の面で十分な結果が得られていない[28][29]。

治療応用[編集]

インターフェロンガンマ-1bは、慢性肉芽腫症(CGD)[30]と大理石骨病[31]の治療に対してFDAの承認を受けている。IFN-γは患者の酸化代謝を改善してカタラーゼ陽性細菌に対する好中球の効力を高めることで、CGDに対して有効性を示す[32]。

IFN-γは特発性肺線維症(IPF)の治療に対しては承認されていない。2002年にInterMune社は、IPFに対する延命効果と軽症から中等症の患者の致死率を70%低下させることを示す第III相試験に関するプレスリリースを行ったが、アメリカ合衆国司法省はプレスリリースに虚偽やミスリーディングな記述が含まれるとして起訴した。InterMune社の最高責任者であるScott Harkonenは治験データを操作したとして2009年に通信詐欺罪で有罪となり、罰金と社会奉仕の宣告を受けた。Harkonenは有罪判決を不服として第9巡回区控訴裁判所に控訴したが、敗訴した[33]。Harkonenは2021年1月20日に完全恩赦を受けた[34]。

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphiaによって行われたフリードライヒ運動失調症の治療におけるIFN-γの役割に関する予備的研究では、短期間(6か月未満)の治療では有効性がみられないことが示された[35][36][37]。一方、トルコの研究者によって6か月以降に患者の歩行や姿勢に有意な改善がみられることが報告されている[38]。

公的な承認は受けていないものの、IFN-γは中等症から重症のアトピー性皮膚炎の患者の治療に対する有効性も報告されている[39][40][41]。具体的には、単純ヘルペスウイルス(HSV)などの感染を起こしやすい患者や幼い患者など、IFN-γの発現が低下している患者に対しては組換えIFN-γによる治療の有望性が示されている[42]。

免疫療法における可能性[編集]

IFN-γはがん細胞の抗増殖状態を増加させる一方で、MHC IやMHC IIの発現をアップレギュレーションし、病原性細胞の認識と除去を向上させる[43]。IFN-γはフィブロネクチンをアップレギュレーションすることで腫瘍構造を変化させ、転移を低下させる[44]。

現時点では、IFN-γはいかなるがんの免疫療法に対しても承認を受けていない。しかしながら、膀胱がんやメラノーマの患者ではIFN-γの投与による生存の改善が観察されている。最も有望な結果が得られているのはステージ2・3の卵巣がんの患者である。がん細胞に対するIFN-γの効果に関するin vitro研究では、IFN-γの抗増殖作用はアポトーシスやオートファジーによって成長阻害または細胞死を引き起こすことが示されている[28]。一方で、CD8陽性リンパ球から分泌されるIFN-γは卵巣がん細胞上のPD-L1をアップレギュレーションし、腫瘍の成長を促進することが報告されていることにも留意が必要である[45]。

HEK293細胞で発現された、哺乳類型の糖鎖修飾がなされたヒト組換えIFN-γは、大腸菌で発現された未修飾のものと比較して治療効果が高いことが報告されている[46]。

相互作用[編集]

IFN-γはIFNGR1、IFNGR2と相互作用することが示されている[47][48]。

疾患[編集]

IFN-γは、シャーガス病など一部の細胞内病原体に対する免疫応答に重要な役割を果たすことが示されている[49]。脂漏性皮膚炎にも関与していることが明らかにされている[50]。

IFN-γはHSVの感染時に大きな抗ウイルス効果を示す。IFN-γはHSVが感染細胞の核内への輸送に依存している微小管構造を破壊し、HSVの複製を阻害する[51][52]。マウスにおけるアシクロビル耐性ヘルペスウイルスに関する研究では、IFN-γ治療はヘルペスウイルス量を大きく減少させることが示されている。IFN-γがヘルペスウイルスの複製を阻害する機構はT細胞に依存していないため、IFN-γはT細胞が減少している患者で効果的な治療法となる可能性がある[53][54][55]。

クラミジア感染は宿主細胞のIFN-γの影響を受ける。ヒトの上皮細胞では、IFN-γはインドールアミン-2,3-ジオキシゲナーゼの発現をアップレギュレーションし、宿主のトリプトファンを枯渇させることでクラミジアの複製を妨げる[56][57]。さらに、齧歯類の上皮細胞では、IFN-γはクラミジアの増殖を阻害するGTPアーゼをアップレギュレーションする[58]。一方でクラミジアも、ヒトと齧歯類の系の双方で宿主側の応答による負の影響を回避する機構を進化させている[59]。

調節[編集]

IFN-γの発現は5' UTRのシュードノット構造によって調節されている[60]。また、マイクロRNAmiR-29によっても直接的もしくは間接的に調節されている[61]。さらに、T細胞ではIFN-γの発現はGAPDHを介して調節されている。この相互作用は3' UTRで行われ、GAPDHの結合はmRNAの翻訳を阻害する[62]。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000111537 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000055170 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Structure of the human immune interferon gene”. Nature 298 (5877): 859–863. (August 1982). Bibcode: 1982Natur.298..859G. doi:10.1038/298859a0. PMID 6180322.

- ^ “Interferon-Like Virus-Inhibitor Induced in Human Leukocytes by Phytohemagglutinin”. Science 149 (3681): 310–311. (July 1965). Bibcode: 1965Sci...149..310W. doi:10.1126/science.149.3681.310. PMID 17838106.

- ^ “Immune specific induction of interferon production in cultures of human blood lymphocytes”. Science 164 (3886): 1415–1417. (June 1969). Bibcode: 1969Sci...164.1415G. doi:10.1126/science.164.3886.1415. PMID 5783715.

- ^ “Release of virus inhibitor from tuberculin-sensitized peritoneal cells stimulated by antigen”. Journal of Immunology 105 (5): 1068–1071. (November 1970). PMID 4321289.

- ^ “Human immune interferon gene is located on chromosome 12”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 157 (3): 1020–1027. (March 1983). doi:10.1084/jem.157.3.1020. PMC 2186972. PMID 6403645.

- ^ a b “IFNG interferon gamma [Homo sapiens (human) - Gene - NCBI]”. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2022年4月16日閲覧。

- ^ “Regulation of Interferon‐γ During Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses”. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. 96. (2007). 41–101. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96002-2. ISBN 978-0-12-373709-0. PMID 17981204

- ^ “The biology of innate lymphoid cells”. Nature 517 (7534): 293–301. (January 2015). Bibcode: 2015Natur.517..293A. doi:10.1038/nature14189. PMID 25592534.

- ^ “Three-dimensional structure of recombinant human interferon-gamma”. Science 252 (5006): 698–702. (May 1991). Bibcode: 1991Sci...252..698E. doi:10.1126/science.1902591. PMID 1902591.

- ^ a b c d e PDB: 1FG9; “Observation of an unexpected third receptor molecule in the crystal structure of human interferon-gamma receptor complex”. Structure 8 (9): 927–936. (September 2000). doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00184-2. PMID 10986460.

- ^ “Cross-regulation of signaling pathways by interferon-gamma: implications for immune responses and autoimmune diseases”. Immunity 31 (4): 539–550. (October 2009). doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.002. PMC 2774226. PMID 19833085.

- ^ a b “The heparan sulfate binding sequence of interferon-gamma increased the on rate of the interferon-gamma-interferon-gamma receptor complex formation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (18): 10919–10925. (May 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.18.10919. PMID 9556569.

- ^ “NMR characterization of the interaction between the C-terminal domain of interferon-gamma and heparin-derived oligosaccharides”. The Biochemical Journal 384 (Pt 1): 93–99. (November 2004). doi:10.1042/BJ20040757. PMC 1134092. PMID 15270718.

- ^ a b “Interferon-gamma binds to heparan sulfate by a cluster of amino acids located in the C-terminal part of the molecule”. FEBS Letters 280 (1): 152–154. (March 1991). doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)80225-R. PMID 1901275.

- ^ “Interferon-Gamma at the Crossroads of Tumor Immune Surveillance or Evasion”. Frontiers in Immunology 9: 847. (2018). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00847. PMC 5945880. PMID 29780381.

- ^ “Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions”. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 75 (2): 163–189. (February 2004). doi:10.1189/jlb.0603252. PMID 14525967.

- ^ “The role of cytokines in the regulation of NK cells in the tumor environment”. Cytokine 117: 30–40. (May 2019). doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2019.02.001. PMID 30784898.

- ^ “Tissue-Specific Macrophage Responses to Remote Injury Impact the Outcome of Subsequent Local Immune Challenge”. Immunity 51 (5): 899–914.e7. (November 2019). doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.10.010. PMC 6892583. PMID 31732166.

- ^ “Induction of Autonomous Memory Alveolar Macrophages Requires T Cell Help and Is Critical to Trained Immunity”. Cell 175 (6): 1634–1650.e17. (November 2018). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.042. PMID 30433869.

- ^ “CD4⁺T cells: differentiation and functions”. Clinical & Developmental Immunology 2012: 925135. (2012). doi:10.1155/2012/925135. PMC 3312336. PMID 22474485.

- ^ “Interferon gamma contributes to initiation of uterine vascular modification, decidual integrity, and uterine natural killer cell maturation during normal murine pregnancy”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 192 (2): 259–270. (July 2000). doi:10.1084/jem.192.2.259. PMC 2193246. PMID 10899912.

- ^ “The role of interferons in early pregnancy”. Gynecological Endocrinology 30 (1): 1–6. (January 2014). doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.743011. PMID 24188446.

- ^ “Effects of products of activated leukocytes (lymphokines and monokines) on the growth of malignant trophoblast cells in vitro”. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 158 (1): 199–203. (January 1988). doi:10.1016/0002-9378(88)90810-1. PMID 2447775.

- ^ a b “Review of the recombinant human interferon gamma as an immunotherapeutic: Impacts of production platforms and glycosylation”. Journal of Biotechnology 240: 48–60. (December 2016). doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.10.022. PMID 27794496.

- ^ “Is Pichia pastoris a realistic platform for industrial production of recombinant human interferon gamma?”. Biologicals 45: 52–60. (January 2017). doi:10.1016/j.biologicals.2016.09.015. PMID 27810255.

- ^ “Interferon gamma-1b. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in chronic granulomatous disease”. Drugs 43 (1): 111–122. (January 1992). doi:10.2165/00003495-199243010-00008. PMID 1372855.

- ^ “Recombinant human interferon gamma therapy for osteopetrosis”. The Journal of Pediatrics 121 (1): 119–124. (July 1992). doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82557-0. PMID 1320672.

- ^ “The use of interferon-gamma therapy in chronic granulomatous disease”. Recent Patents on Anti-Infective Drug Discovery 3 (3): 225–230. (November 2008). doi:10.2174/157489108786242378. PMID 18991804.

- ^ “Drug Marketing. The line between scientific uncertainty and promotion of snake oil”. BMJ 347: f5687. (September 2013). doi:10.1136/bmj.f5687. PMID 24055923.

- ^ “Statement from the Press Secretary Regarding Executive Grants of Clemency”. whitehouse.gov (2021年1月20日). 2022年4月30日閲覧。

- ^ “IFN-γ for Friedreich ataxia: present evidence”. Neurodegenerative Disease Management 5 (6): 497–504. (December 2015). doi:10.2217/nmt.15.52. PMID 26634868.

- ^ “Open-label pilot study of interferon gamma-1b in Friedreich ataxia”. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 132 (1): 7–15. (July 2015). doi:10.1111/ane.12337. PMID 25335475.

- ^ “Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of interferon-γ 1b in Friedreich Ataxia”. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 6 (3): 546–553. (March 2019). doi:10.1002/acn3.731. PMC 6414489. PMID 30911578.

- ^ “Efficacy and Tolerability of Interferon Gamma in Treatment of Friedreich's Ataxia: Retrospective Study”. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi 57 (4): 270–273. (December 2020). doi:10.29399/npa.25047. PMC 7735154. PMID 33354116.

- ^ “Atopic dermatitis: systemic immunosuppressive therapy”. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 27 (2): 151–155. (June 2008). doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.04.004. PMID 18620137.

- ^ “Long-term therapy with recombinant interferon-gamma (rIFN-gamma) for atopic dermatitis”. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 80 (3): 263–268. (March 1998). doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62968-7. PMID 9532976.

- ^ “Recombinant interferon gamma therapy for atopic dermatitis”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 28 (2 Pt 1): 189–197. (February 1993). doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70026-p. PMID 8432915.

- ^ “Recent considerations in the use of recombinant interferon gamma for biological therapy of atopic dermatitis”. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 16 (4): 507–514. (2016). doi:10.1517/14712598.2016.1135898. PMC 4985031. PMID 26694988.

- ^ “Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ): Exploring its implications in infectious diseases”. Biomolecular Concepts 9 (1): 64–79. (May 2018). doi:10.1515/bmc-2018-0007. PMID 29856726.

- ^ “Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: a review”. Biomarker Research 8 (1): 49. (2020-09-29). doi:10.1186/s40364-020-00228-x. PMC 7526126. PMID 33005420.

- ^ “IFN-γ from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and promotes progression of ovarian cancer”. British Journal of Cancer 112 (9): 1501–1509. (April 2015). doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.101. PMC 4453666. PMID 25867264.

- ^ “Improved therapeutic efficacy of mammalian expressed-recombinant interferon gamma against ovarian cancer cells”. Experimental Cell Research 359 (1): 20–29. (October 2017). doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.08.014. PMID 28803068.

- ^ “Observation of an unexpected third receptor molecule in the crystal structure of human interferon-gamma receptor complex”. Structure 8 (9): 927–936. (September 2000). doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00184-2. PMID 10986460.

- ^ “Interaction between the components of the interferon gamma receptor complex”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 270 (36): 20915–20921. (September 1995). doi:10.1074/jbc.270.36.20915. PMID 7673114.

- ^ “IL18 Gene Variants Influence the Susceptibility to Chagas Disease”. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10 (3): e0004583. (March 2016). doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004583. PMC 4814063. PMID 27027876.

- ^ “Investigations of seborrheic dermatitis. Part I. The role of selected cytokines in the pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis”. Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej 66: 843–847. (November 2012). doi:10.5604/17322693.1019642. PMID 23175340.

- ^ “Complexity of Interferon-γ Interactions with HSV-1”. Frontiers in Immunology 5: 15. (2014-02-06). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00015. PMC 3915238. PMID 24567732.

- ^ “Microtubule-mediated transport of incoming herpes simplex virus 1 capsids to the nucleus”. The Journal of Cell Biology 136 (5): 1007–1021. (March 1997). doi:10.1083/jcb.136.5.1007. PMC 2132479. PMID 9060466.

- ^ “Beta interferon plus gamma interferon efficiently reduces acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus infection in mice in a T-cell-independent manner”. The Journal of General Virology 91 (Pt 3): 591–598. (March 2010). doi:10.1099/vir.0.016964-0. PMID 19906941.

- ^ “Alpha/Beta interferon and gamma interferon synergize to inhibit the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1”. Journal of Virology 76 (22): 11541–11550. (November 2002). doi:10.1128/JVI.76.22.11541-11550.2002. PMC 136787. PMID 12388715.

- ^ “Immune control of herpes simplex virus during latency”. Current Opinion in Immunology 16 (4): 463–469. (August 2004). doi:10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.003. PMID 15245740.

- ^ “The role of IFN-gamma in the outcome of chlamydial infection”. Current Opinion in Immunology 14 (4): 444–451. (August 2002). doi:10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00361-8. PMID 12088678.

- ^ “Relationship between interferon-gamma, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and tryptophan catabolism”. FASEB Journal 5 (11): 2516–2522. (August 1991). doi:10.1096/fasebj.5.11.1907934. PMID 1907934.

- ^ “The p47 GTPases Igtp and Irgb10 map to the Chlamydia trachomatis susceptibility locus Ctrq-3 and mediate cellular resistance in mice”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (38): 14092–14097. (September 2006). Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10314092B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603338103. PMC 1599917. PMID 16959883.

- ^ “Chlamydial IFN-gamma immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (30): 10658–10663. (July 2005). Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10210658N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504198102. PMC 1180788. PMID 16020528.

- ^ “Human interferon-gamma mRNA autoregulates its translation through a pseudoknot that activates the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR”. Cell 108 (2): 221–232. (January 2002). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00616-5. PMID 11832212.

- ^ “MicroRNA targets in immune genes and the Dicer/Argonaute and ARE machinery components”. Molecular Immunology 45 (7): 1995–2006. (April 2008). doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.10.035. PMC 2678893. PMID 18061676.

- ^ “Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis”. Cell 153 (6): 1239–1251. (June 2013). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. PMC 3804311. PMID 23746840.

関連文献[編集]

- A commotion in the blood: life, death, and the immune system. New York: Henry Holt. (1997). ISBN 978-0-8050-5841-3

- “The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting”. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 13 (2): 95–109. (April 2002). doi:10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00038-7. PMID 11900986.

- “The role of IFN-gamma in immune responses to viral infections of the central nervous system”. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 13 (6): 441–454. (December 2002). doi:10.1016/S1359-6101(02)00044-8. PMID 12401479.

- “Interleukin-13 in the skin and interferon-gamma in the liver are key players in immune protection in human schistosomiasis”. Immunological Reviews 201: 180–190. (October 2004). doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00195.x. PMID 15361241.

- “Nef: "necessary and enforcing factor" in HIV infection”. Current HIV Research 3 (1): 87–94. (January 2005). doi:10.2174/1570162052773013. PMID 15638726.

- “Modulation of HIV-1 transcription by cytokines and chemokines”. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 5 (12): 1093–1101. (December 2005). doi:10.2174/138955705774933383. PMID 16375755.

- “The significance of interferon-gamma-triggered internalization of tight-junction proteins in inflammatory bowel disease”. Science's STKE 2006 (316): pe1. (January 2006). doi:10.1126/stke.3162006pe1. PMID 16391178.

- “Interferon-gamma axis in graft arteriosclerosis”. Circulation Research 100 (5): 622–632. (March 2007). doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000258861.72279.29. PMID 17363708.