Whitechapel Vigilance Committee

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

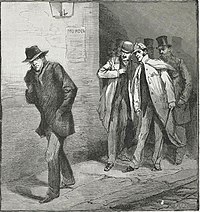

The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee was a group of local civilian volunteers who patrolled the streets of London's Whitechapel district during the period of the Whitechapel murders of 1888. The volunteers were active mainly at night, assisting the Metropolitan Police in the search of the unknown murderer known as the "Whitechapel Murderer", "Leather Apron" and, latterly, "Jack the Ripper".

Formation[edit]

The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee was founded by sixteen tradesmen from the Whitechapel and Spitalfields districts, who were concerned that the killings were affecting businesses in the area.[1][2] The committee was led by a local builder named George Lusk, who was elected chairman during its first meeting on 10 September 1888.[3]

Other committee members included publican Joseph Aarons (treasurer), Mr. B. Harris (secretary),[4] and Messrs. Barnett, Cohen, H. A. Harris, Hodgins, Houghton, Isaacs, Jacobs, Laughton, Lindsay, Lord, Mitchell, Reeves, and Rogers. The Daily Telegraph reported on 5 October 1888 that the leading members of the committee were "drawn principally from the trading class, and include a builder, a cigar-manufacturer, a tailor, a picture-frame maker, a licensed victualler, and 'an actor.'"[5] The latter may have been the entertainer Charles Reeves.[6]

Civic duties[edit]

Members of the committee were unhappy with the level of protection the local community was receiving from the Metropolitan Police, so it introduced its own system of local patrols, using hand-picked unemployed men to monitor the streets of the East End every evening from midnight to between four and five the next morning. Each of these men received a small wage from the committee, and each patrolled a particular beat, being armed with a police whistle, a pair of galoshes and a strong stick. The committee itself met each evening at nine in a public house called The Crown, and once the establishment closed at 12.30am the committee members would inspect and join the patrols. These patrols were shortly to be joined by those of the Working Men's Vigilance Committee.[7]

Publicity[edit]

As chairman of the committee, Lusk's name appeared in national newspapers and upon posters in and around Whitechapel, appealing for information concerning the identity of Jack the Ripper and complaining about the lack of a reward for such information from the British government. Due to this publicity, Lusk received threatening letters through the post, allegedly from the killer. He is also mentioned in a letter dated 17 September 1888, reportedly discovered among archive materials in the late 20th century; however, most experts dismiss this as a modern hoax.[8]

On 30 September 1888, the committee members wrote to the government under Lord Salisbury in an attempt to persuade them to offer a reward for information leading to the apprehension of the Ripper. When the Home Secretary Henry Matthews refused this request, the committee offered its own reward.[3] The committee also employed two private detectives, Mr. Le Grand (or Grand) and Mr. J. H. Batchelor,[4] to investigate the murders without the involvement of the police.

Correspondence[edit]

The "From Hell" letter, which was sent with half of a preserved human kidney, was personally addressed to Lusk, who received the parcel on 16 October 1888.[9] The letter was postmarked on the previous day.[10]

Many scholars[11] of the Ripper murders regard this letter as being the communication most likely to have been sent by the actual murderer.[12]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Facts, p. 119

- ^ Jack the Ripper – Through the Mists of Time ISBN 978-1-782-28168-9 p. 22

- ^ a b "Jack the Ripper Timeline". Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

- ^ a b Eddleston, John J. 'Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia' Published by ABC-CLIO (2001) pg 139 ISBN 1-57607-414-5

- ^ Daily Telegraph 5 October 1888

- ^ "Charles Reeves". Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

- ^ Sugden Philip 'The Complete History of Jack the Ripper' Robinson, London (1995)

- ^ "Ripper Letters". Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

- ^ "The East London Horrors. An Extraordinary Parcel". Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

- ^ Science Images and Popular Images of the Sciences ISBN 978-1-134-17580-2 p. 127

- ^ Sugden Philip, Ibid <citation #5>, p. 273

- ^ "From Hell: Fact or Fiction?". Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

Cited works and further reading[edit]

- Begg, Paul (2006). Jack the Ripper: The Facts. London: Anova Books. ISBN 1-86105-687-7

- Eddleston, John J. (2002). Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia. London: Metro Books. ISBN 1-84358-046-2

- Evans, Stewart P.; Skinner, Keith (2001). Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2549-3

- Lightbody, Bryan (2007). Whitechapel. Milton Keynes: Author House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-425-96181-7

External links[edit]

Media related to Whitechapel Vigilance Committee at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Whitechapel Vigilance Committee at Wikimedia Commons- The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee on the Casebook: Jack the Ripper website

- The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee on the London Walks website