Viedma (volcano)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Viedma | |

|---|---|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,500 m (4,900 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 49°22′S 73°19′W / 49.367°S 73.317°W[2] |

| Geography | |

| Location | Argentina/Chile |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Subglacial volcano |

| Last eruption | November 1988[1] |

Viedma (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbjeðma]) is a subglacial volcano whose existence is questionable. It is supposedly located below the ice of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, an area disputed between Argentina and Chile. The 1988 eruption deposited ash and pumice on the ice field and produced a mudflow that reached Viedma Lake.[1] The exact position of the edifice is unclear, both owing to the ice cover and because the candidate position, the "Viedma Nunatak", does not clearly appear to be of volcanic nature.

Geography and geomorphology[edit]

Viedma is located in the southern Patagonian Andes,[3] southwest of Mount FitzRoy.[4] The lake of the same name lies southwest of the volcano. The area is poorly accessible[2] and the volcanic history poorly known.[3]

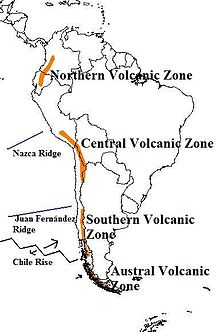

Viedma is part of the Austral Volcanic Zone.[2] This volcanic zone consists of six volcanoes, from north to south Lautaro, Aguilera, Viedma, Reclus, Monte Burney and Fueguino.[3] These volcanoes form a 700 kilometres (430 mi) long chain of volcanoes, the most southern of which is a volcanic complex of lava domes and lava flows on Cook Island.[5]

Few things are known with certainty about the volcanic edifice of Viedma as it is mostly buried beneath glacial ice[6] and the "Viedma Nunatak" was later revealed to not be a volcano.[7] In 1956 Louis Lliboutry proposed that volcanic activity may occur in fissure vents buried beneath glaciers; between eruptions they would be concealed below the ice;[8] Lliboutry considered dark bands on the ice to be tephra deposits, a view supported by a 1958-1959 expedition that found pumice on the Viedma Glacier.[9] Other reports of volcanic phenomena in the region exist, and the existence of a large caldera beneath the Southern Patagonian Ice Field has been suggested as an explanation for volcanism there.[10]

Viedma Nunatak[edit]

The Viedma Nunatak is commonly interpreted to be the site of the volcano,[11] after observations made in 1944-1945 and 1950 by survey flights including controversial sightings of fumaroles which also led to the nunatak becoming known as the "Volcan Viedma";[12][8] but the lack of clear evidence[10] and the difficulty of field sampling has rendered its identification with the Viedma vent contentious.[11]

The nunatak is about 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) high above sea level. Most of the mountain is buried beneath the Viedma Glacier of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field and only parts of it crop out.[2] The outcropping nunatak is elongated in north-south direction.[13] A number of structures interpreted as craters and concave depressions are found especially on the southern part of the volcano, some of which are lined up in north-south direction. The northern sector of the volcano was apparently more heavily affected by glacial erosion; conversely, several craters in the southern sector appear to be young.[14] The nunatak shows clear evidence of glacial action, including glacial striations and coverage by glacial drifts; the Viedma glacier may once have crossed the nunatak in its central part.[15] Rock samples taken from the nunatak are Jurassic metamorphic rocks, including gneiss and schists,[11] and no evidence of magmatic rocks was found in a 1958-1959 expedition.[9]

Different observations have yielded different sizes and numbers of supposed craters; González-Ferrán et al. 1995 reported several craters and calderas with sizes ranging 1.5–4 kilometres (0.93–2.49 mi), while Kobayashi et al. 2010 observed fewer craters and none of them larger than 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi).[14] These craters were later interpreted as being actually glacial cirques containing tarn lakes.[15]

Geology[edit]

Off the southernmost west coast of South America, the Antarctic Plate subducts beneath the South American Plate at a rate of 3 centimetres per year (1.2 in/year).[16] This subduction process is responsible for volcanism in the Austral Volcanic Zone.[17] The Austral Volcanic Zone is one of four volcanic zones in the Andes, the other three are the Northern Volcanic Zone, the Central Volcanic Zone and the Southern Volcanic Zone, all of which are separated from the Austral Volcanic Zone and each other by gaps where no volcanic activity occurs. Unlike the Austral Volcanic Zone, volcanism in these other zones is controlled by the subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South American Plate.[18]

The Austral Volcanic Zone was identified as such in 1976, but some volcanoes were identified and localized later. Owing to their similar composition the three northerly volcanoes Lautaro, Viedma and Aguilera are grouped as the "northern Austral Volcanic Zone". Volcanism in the Austral Volcanic Zone is not well known before the Holocene; it is likely that a lull of volcanism occurred before the Pliocene while the Chile Triple Junction was being subducted in the region. Magmas from the Austral Volcanic Zone are adakitic owing to the melting of the subducting slab and the interaction of these melts with the crust and mantle.[18]

The basement consists of metamorphic rocks of Paleozoic age. Outcrops of the basement are found around the volcano and could even occur on the edifice that crops out from the glaciers.[19] The regional basement is formed by these Paleozoic and younger metamorphic and sedimentary rocks as well.[18]

Composition[edit]

Viedma like other volcanoes of the Austral Volcanic Zone has erupted andesite and dacite. Phenocrysts include amphibole, biotite, hypersthene and plagioclase; orthoclase, plagioclase and pyroxene also occur as xenoliths. The rocks form a calcalkaline suite,[20] but there is also an adakitic signature.[2] The xenoliths may reflect a crustal contamination of the magma erupted at Viedma.[20]

Eruption history[edit]

Tephra attributed to Viedma has been found in the Laguna Potrok Aike,[21] including three tephra layers 26,991 - 29,416, 40,656 - 48,219 and 41,555 - 57,669 years before present which may originate either on Viedma or on Lautaro.[22]

Viedma has erupted during the Holocene;[6] a tephra found in Lago Cardiel and dated 3,345 - 3,010 years before present may have originated at Viedma, although Aguilera and Lautaro are also candidate source volcanoes.[23] Due to the absence of traces of volcanism at Viedma Nunatak the Global Volcanism Program removed its entry for Viedma in 2019.[7]

Historical[edit]

Many observations referring to volcanic activity on the Southern Patagonian Ice Field exist, including reports of ashfalls, layers of tephra on glaciers and columns of smoke rising from the ice.[8]

A subglacial eruption occurred in 1988, depositing ash and pumice on the Viedma Glacier. These materials later gave rise to a lahar.[2] The eruption had melted part of the ice and formed a network of valleys; it was assumed that it had taken place at some point between September and November of that year.[24]

Hazards[edit]

There are no major population centres close to any volcano in the Austral Volcanic Zone, and the volcanoes are largely unmonitored. Among the know eruptions are large Holocene explosive eruptions, while historical eruptions took place in 1908 at Reclus and 1910 at Monte Burney.[5] Future eruptions of volcanoes in the Austral Volcanic Zone may lead to ash fall at large distances from the volcano, including interruptions in air traffic and direct ash damage.[25] Viedma is considered to be Argentina's 10th most dangerous volcano.[26]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Viedma". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2005-02-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Kobayashi et al. 2010, p. 434.

- ^ a b c Kilian 1990, p. 301.

- ^ Shipton 1960, p. 393.

- ^ a b Perucca, Alvarado & Saez 2016, p. 552.

- ^ a b Perucca, Alvarado & Saez 2016, p. 553.

- ^ a b @SmithsonianGVP (August 15, 2019). "Global Volcanism Program" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c Shipton 1960, p. 389.

- ^ a b Shipton 1960, p. 391.

- ^ a b Mateo, Mateo (9 December 2008). "Registro Histórico de Antecedentes Volcánicos y Sísmicos en la Patagonia Austral y la Tierra del Fuego. Historic Record of Volcanic and Seismic Precedents in Southern Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego". Magallania (in Spanish). 36 (2): 12. ISSN 0718-2244.

- ^ a b c Blampied et al. 2012, p. 380.

- ^ Lliboutry, Luis (1956). Nieves y glaciares de Chile: fundamentos de glaciologia (in Spanish). Ediciones de la Universidad de Chile. p. 413.

- ^ Kobayashi et al. 2010, p. 436.

- ^ a b Kobayashi et al. 2010, p. 435.

- ^ a b Blampied et al. 2012, p. 381.

- ^ Kilian 1990, p. 301,302.

- ^ Stern, Charles R. (1 February 2008). "Holocene tephrochronology record of large explosive eruptions in the southernmost Patagonian Andes". Bulletin of Volcanology. 70 (4): 435. Bibcode:2008BVol...70..435S. doi:10.1007/s00445-007-0148-z. hdl:10533/139124. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 140710192.

- ^ a b c Stern, Charles R. (2004). "Active Andean volcanism: its geologic and tectonic setting". Revista Geológica de Chile. 31 (2): 161–206. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082004000200001. ISSN 0716-0208.

- ^ Kobayashi et al. 2010, p. 438.

- ^ a b Kilian 1990, p. 303.

- ^ Wastegård, Stefan (November 2012). "Tephrostratigraphy of the Potrok Aike Maar Lake Sediment Sequence". Quaternary International. 279–280: 528–529. Bibcode:2012QuInt.279U.528W. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.08.1843. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Wastegård, S.; Veres, D.; Kliem, P.; Hahn, A.; Ohlendorf, C.; Zolitschka, B. (July 2013). "Towards a late Quaternary tephrochronological framework for the southernmost part of South America – the Laguna Potrok Aike tephra record". Quaternary Science Reviews. 71: 84. Bibcode:2013QSRv...71...81W. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.10.019. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ Markgraf, Vera; Bradbury, J. Platt; Schwalb, Antje; Burns, Stephen J.; Stern, Charles; Ariztegui, Daniel; Gilli, Adrian; Anselmetti, Flavio S.; Stine, Scott; Maidana, Nora (27 July 2016). "Holocene palaeoclimates of southern Patagonia: limnological and environmental history of Lago Cardiel, Argentina". The Holocene. 13 (4): 583. doi:10.1191/0959683603hl648rp. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 129856246.

- ^ Kilian 1990, p. 302.

- ^ Perucca, Alvarado & Saez 2016, p. 557.

- ^ Garcia, Sebastian; Badi, Gabriela (1 November 2021). "Towards the development of the first permanent volcano observatory in Argentina". Volcanica. 4 (S1): 26. doi:10.30909/vol.04.S1.2148. ISSN 2610-3540.

Sources[edit]

- Blampied, Jorge; Barberon, Vanesa; Ghiglione, Matías; Leal, Pablo; Ramos, Víctor (August 2012). "Disambiguation of the Nunatak Viedma: a basement block previously confused as a volcanic center" (PDF). Sernageomin. Antofagasta: 13th Chilean Geological Congress. pp. 380–382. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- Kilian, R. (15–17 May 1990). The australandean volcanic zone (south Patagonia) (PDF). Grenoble, France: ORSTOM. ISBN 978-2-7099-0993-8.

- Kobayashi, Chiaki; Orihashi, Yuji; Hiarata, Daiji; Naranjo, Jose; Kobayashi, Makoto; Anma, Ryo (17 August 2010). "Compositional variations revealed by ASTER image analysis of the Viedma Volcano, southern Andes Volcanic Zone". Andean Geology. 37 (2): 433–441. doi:10.5027/andgeoV37n2-a09. ISSN 0718-7106.

- Perucca, Laura; Alvarado, Patricia; Saez, Mauro (1 July 2016). "Neotectonics and seismicity in southern Patagonia". Geological Journal. 51 (4): 545–559. Bibcode:2016GeolJ..51..545P. doi:10.1002/gj.2649. hdl:11336/12998. ISSN 1099-1034.

- Shipton, Eric (1960). "Volcanic Activity on the Patagonian Ice Cap". The Geographical Journal. 126 (4): 389–396. Bibcode:1960GeogJ.126..389S. doi:10.2307/1793373. JSTOR 1793373.