The Fourth Kind

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The Fourth Kind | |

|---|---|

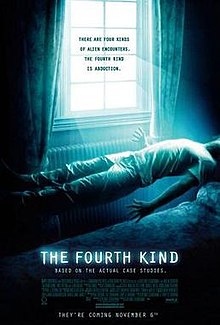

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Olatunde Osunsanmi |

| Screenplay by | Olatunde Osunsanmi |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | Milla Jovovich Will Patton Elias Koteas |

| Cinematography | Lorenzo Senatore |

| Edited by | Paul Covington |

| Music by | Atli Örvarsson |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million |

| Box office | $47.7 million[1] |

The Fourth Kind is a 2009 science fiction thriller film[2] directed by Olatunde Osunsanmi and featuring a cast of Milla Jovovich, Elias Koteas, Corey Johnson, Will Patton, Charlotte Milchard, Mia Mckenna-Bruce, Yulian Vergov, and Osunsanmi. The title is derived from the expansion of J. Allen Hynek's classification of close encounters with aliens, in which the fourth kind denotes alien abductions.

The film is a pseudodocumentary—purporting to be a dramatic re-enactment of true events that occurred in Nome, Alaska - in which a psychologist uses hypnosis to uncover memories of alien abduction from her patients, and finds evidence suggesting that she may have been abducted as well. At the beginning of the film, Jovovich informs the audience this entire movie is actually real, that she will be playing a character based on a real person named Abigail Tyler, and that the film will feature archival footage of the real Tyler. The "Abigail Tyler" seen in the archival footage is played by Charlotte Milchard, and at various points throughout the film, the archival footage scenes and accompanying dramatic re-enactments are presented side by side.[3][4]

The film received negative reviews and grossed $47.7 million worldwide.[5]

Plot[edit]

Chapman University hosts a televised interview with psychologist Dr. Abigail "Abbey" Tyler, who describes a series of events that occurred in Nome, Alaska that culminated in an alleged alien abduction in October 2000.

In a re-enactment of events occurring in August 2000, Abbey's husband, Will, is murdered, leaving her to raise their two children, Ashley and Ronnie. Abbey tapes hypnotherapy sessions with patients with shared experiences of a white owl staring at them as they sleep before creatures attempt to enter their homes. That night, Abbey is called by the police because one of her patients is holding his wife and two children at gunpoint. He states that he remembers everything and asks what "Zimabu Eter" means. Despite Abbey's pleas, he murders his family and commits suicide.

Abbey suspects that these patients may have been victims of an alien abduction. There is evidence that she herself may have been abducted, when an assistant gives her a tape recorder which plays the sound of something entering her home and attacking her. The attacker speaks an unknown language and Abbey has no memory of the incident. Abel Campos, a colleague from Anchorage, is suspicious of the claims. Abbey calls upon Dr. Awolowa Odusami, a specialist in ancient languages who was a contact of her late husband, to identify the language on the tape. Odusami identifies it as Sumerian.

Another patient, Scott, wishes to communicate. He admits that there was no owl and speaks of "them," but cannot remember anything further and begs Abbey to come to his home to hypnotize him. Under hypnosis, he begins hovering above his bed, while a voice speaking through Scott orders Abbey in Sumerian to end her study. Later, Sheriff August arrives, telling her that Scott is paralyzed from the neck down. Believing Abbey is responsible, August tries to arrest her. Campos comes to her defense and confirms her story. August instead places her under guard inside her house.

A police officer watches Abbey's house when a large black triangular object appears in the sky. The image distorts, but the officer is heard describing people being pulled out of the house and calls for backup. Deputies rush into the house, finding Ronnie and Abbey, who says Ashley was taken. A disbelieving August accuses her of kidnapping Ashley and removes Ronnie from her custody.

Abbey undergoes hypnosis in an attempt to make contact with the beings responsible and reunite with her daughter. Hypnotized, Abbey recalls that she witnessed Ashley's abduction and was also abducted herself. An alien presence communicates with Abbey, who begs for Ashley's return. It states Ashley will never come back before referring to itself as "God". When the encounter ends, Campos and Odusami rush over to the now unconscious Abbey and then notice something offscreen. The image distorts again as a voice yells "Zimabu Eter!" before resolving to show that all three are gone. Abbey wakes up in a hospital with a broken neck. August reveals that Will had committed suicide, and Abbey's belief that he was murdered was a delusion.

The re-enactment ends and, back in the present, Abbey states that she, Campos and Odusami were abducted during the hypnosis session but cannot recall their experiences. She is asked how anyone can take her claims of alien abduction seriously if she was proven to be delusional about her husband's death. Abbey states that she has no choice but to believe that Ashley is still alive. Then Abbey breaks down in tears.

Abbey is cleared of all charges against her, leaves Alaska for the East Coast, where her health deteriorates to the point of requiring constant care. Campos remains a psychologist and Odusami becomes a professor at a Canadian university. Both men, as well as August, refuse to be involved with the interview, while Ronnie remains estranged from Abbey, still blaming her for Ashley's disappearance.

Cast[edit]

- Milla Jovovich as a re-enactment of Abbey Tyler

- Charlotte Milchard, credited only as "Nome resident", portrays the "real" Dr. Abigail Emily Tyler.

- Will Patton as Sheriff August

- Hakeem Kae-Kazim as Awolowa Odusami

- Corey Johnson as Tommy Fisher

- Enzo Cilenti as Scott Stracinsky

- Elias Koteas as Abel Campos

In addition, Jovovich provides opening and dialogue as herself, setting the pretext of the pseudo-documentary's "true" events; as a further pretext of the pseudo-documentary, "Dr. Abigail Emily Tyler" is shown in the closing tombstone credits as having "appeared" in the film. During the fictional "real" footage, the interviewer is played by the director-screenwriter of this entire endeavour, Olatunde Osunsanmi.

Production[edit]

This is the first major film by writer and director Olatunde Osunsanmi, who is a protégé of independent film director Joe Carnahan.[6] The movie is set up as a re-enactment of allegedly original documentary footage. It also uses supposedly "never-before-seen archival footage" that is integrated into the film.[7][4]

The Fourth Kind was shot in Bulgaria and Squamish, British Columbia, Canada. The lush, mountainous setting of Nome in the film bears little resemblance to the actual Nome, Alaska, which sits amidst the fringes of the arctic tree line, where trees can only grow about 8 ft tall due to the permafrost on the shore of the Bering Sea.[citation needed]

To promote the film, Universal Pictures created a website with fake news stories supposedly taken from real Alaska newspapers, including the Nome Nugget and the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. The newspapers sued Universal, eventually reaching a settlement where Universal would remove the fake stories and pay $20,000 to the Alaska Press Club and a $2,500 contribution to a scholarship fund for the Calista Corporation.[8]

Critical reception[edit]

The Fourth Kind received mainly negative reviews from critics. The film has an 18% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 114 reviews. The site's consensus reads "While it boasts a handful of shocks, The Fourth Kind is hokey and clumsy and makes its close encounters seem eerily mundane."[9]

Critic Roger Ebert gave it one and a half stars out of four, comparing it unfavorably to Paranormal Activity and The Blair Witch Project, while praising Milla Jovovich's acting.[10]

According to the Anchorage Daily News, "Nomeites didn't much like the film exploiting unexplained disappearances of Northwest Alaskans, most of whom likely perished due to exposure to the harsh climate, as science fiction nonsense. The Alaska press liked even less the idea of news stories about unexplained disappearances in the Nome area being used to hype some "kind" of fake documentary".[11]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called the film "rote and listless."[12]

CNN reviewer Breanna Hare criticized The Fourth Kind for "marketing fiction as truth". Nome, Alaska Mayor Denise Michels called it "Hollywood hooey". According to Michels, "people need to realize that this is a science fiction thriller". Michels also compared the film to The Blair Witch Project, saying, "we're just hoping the message gets out that this is supposed to be for entertainment."[13]

References[edit]

- ^ The Fourth Kind Archived 2023-08-31 at the Wayback Machine. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ "'The 4th Kind' Banners Go Through Step by Step - Bloody Disgusting". www.bloody-disgusting.com. 10 October 2009.

- ^ Wainio, Wade (3 October 2018). "Sci-Fi: The Fourth Kind may bend truth, but it also bends minds". Fansided.com. FanSided (Minute Media). Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b Woerner, Meredith (27 June 2014). "Fact Check: Are These Horror Films Really "Based On Actual Events"?". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Box Office Mojo: The Fourth Kind". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ^ "Milla Gets a Thriller". Wired News. 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Tyler, Josh (2009-08-13). "The Fourth Kind Trailer: A Movie For Believers". Cinema Blend. Archived from the original on 2009-08-15. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Richardson, Jeff (2008-11-11). "Alaska newspapers, movie studio reach settlement over 'Fourth Kind'". Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. Retrieved 2012-03-16.[permanent dead link]

- ^ The Fourth Kind at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 4, 2009). The Fourth Kind (review). Chicago Sun-Times

- ^ Medred, Craig. "'The Fourth Kind' pays for telling a big fib". adn.com. Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Entertainment Weekly November 20, 2009 pg. 71. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Hare, Breanna. "'The Fourth Kind' of fake?". CNN.com. CNN. Retrieved 23 January 2018.