Tangena

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

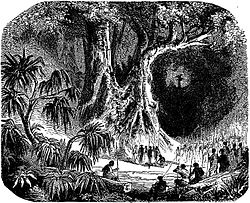

Tangena is the indigenous name for the tree species Cerbera manghas (family Apocynaceae) of Madagascar, which produces seeds - containing the highly toxic cardiac glycoside cerberin - that were used historically on the island for trials by ordeal, held in order to determine the guilt or innocence of an accused party.

The tradition of the tangena ordeal, which has taken various forms over time, dates to at least the 16th century in Imerina, the central highland kingdom that would eventually come to rule the population of nearly the entire island four centuries later. It has been estimated that the poison may have been responsible for the death of as much as 2% of the population of the central province of Madagascar each year on average, with much higher mortality rates at specific periods, such as during the reign of Queen Ranavalona I (1828–1861), when the ordeal was heavily used.

The belief in the genuineness and accuracy of the tangena ordeal was so strongly held among all that innocent people suspected of an offence did not hesitate to subject themselves to it; some even showed eagerness to be tested. The use of ritual poison in Madagascar was abolished in 1863 by King Radama II, but its use persisted for at least several decades after being officially banned.

Etymology[edit]

The name Tangena - designating both the plant and the ordeal in which it was used - is derived from a word in the official (highland) dialect of the Malagasy language, tangaina, meaning "swearing" or "oath taking".[1]

History[edit]

The precise dates and origins of the tangena ordeal on Madagascar are unknown. The 19th century transcription of Merina oral history, Tantara ny Andriana eto Madagasikara, references the use of tangena by the Merina king Andrianjaka (1612–1630), describing changes in its practice. This early 17th-century king imposed an intimidating change to the traditional form of justice: rather than administering tangena poison to an accused person's rooster to determine their innocence by the creature's survival, the poison would instead be ingested by the accused himself.[2] By Andrianjaka's time, the ordeal was already a well-established and respected form of traditional justice, suggesting the practice must have originated no later than the 16th century.[3]

In the early 19th century, tangena constituted one of the chief measures by which Queen Ranavalona maintained order within her realm. A poison was extracted from the nut of the native tangena shrub and ingested, with the outcome determining innocence or guilt. If nobles (andriana) or freemen (hova) were compelled to undergo the ordeal, the poison was typically administered to the accused only after dog and rooster stand-ins had already died from the poison's effects, while among members of the slave class (andevo), the ordeal required them to immediately ingest the poison themselves.[4] The accused would be fed the poison along with three pieces of chicken skin: if all three pieces of skin were vomited up then innocence was declared, but death or a failure to regurgitate all three pieces of skin indicated guilt.[5] Those who died were declared sorcerers. According to custom, the families of the dead were not permitted to bury them within the family tomb, but rather had to inter them in the ground at a remote, inhospitable location, with the head of the corpse turned to the south (a mark of dishonor).[6] According to 19th-century Malagasy historian Raombana, in the eyes of the greater populace, the tangena ordeal was believed to represent a sort of celestial justice in which the public placed their unquestioning faith, even to the point of accepting a verdict of guilt in a case of innocence as a just but unknowable divine mystery.[4]

Residents of Madagascar could accuse one another of various crimes, including theft, Christianity and especially witchcraft, for which the ordeal of tangena was routinely obligatory. On average, an estimated 20 to 50 percent of those who underwent the ordeal died. In the 1820s, the tangena ordeal caused about 1,000 deaths annually. This average rose to around 3,000 annual deaths between 1828 and 1861. In 1838, it was estimated that as many as 100,000 people in Imerina died as a result of the tangena ordeal, constituting roughly 20 percent of the population.

The tangena ordeal was outlawed in 1863 by Radama II. Furthermore, Radama decreed that those who had died from the tangena ordeal would no longer be considered guilty of sorcery, and their bodies could once again be buried in family tombs. This decree was hailed with joy and prompted mass re-interments, as nearly every family in mid-19th century Imerina had lost at least one family member in a tangena ordeal.[6] Despite this royal decree, the practice continued secretly in Imerina and openly in other parts of the island.[4][7] One of the key conditions that Radama's widow, Rasoherina, was obliged to accept by her ministers before they would agree to her succession, was continued adherence to the abolishment of the tangena ordeal.[8][9]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Boiteau, Pierre (1999). "tangena". Dictionnaire des noms malgaches de végétaux (in French). Vol. III. Editions Alzieu – via Malagasy Dictionary and Malagasy Encyclopedia.

- ^ Kent (1970), p.

- ^ Callet (1908), p.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Gwyn (October 1991). "The state and pre-colonial demographic history: the case of nineteenth century Madagascar". Journal of African History. 23 (3): 415–445. doi:10.1017/S0021853700031534.

- ^ Oliver (1886), p.

- ^ a b Chapus (1953), p. 32

- ^ De Maleissye (1991), p.

- ^ Cousins (1895), p.

- ^ Randriamamony (), pp. 529–534

References[edit]

- Callet, François (1972) [1908]. Tantara ny andriana eto Madagasikara (histoire des rois) (in French). Antananarivo: Imprimerie catholique.

- Chapus, G.S.; Mondain, G. (1953). Un homme d'etat malgache: Rainilaiarivony (in French). Paris: Editions Diloutremer.

- Cousins, William Edward. Madagascar of to-day: A sketch of the island, with chapters on its past. The Religious Tract Society, 1895.

- De Maleissye, J., 1991. In: Bourin, F. (Ed.), Histoire du poison. Paris.

- Kent, Raymond (1970). Early Kingdoms in Madagascar: 1500–1700. London: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Island and its Former Dependencies, Volume 1. New York: Macmillan.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: An historical and descriptive account of the island and its former dependencies. Volume 2. London: Macmillan. p. 2.

- Randriamamonjy, Frédéric. Tantaran'i Madagasikara Isam-Paritra (The history of Madagascar by Region).