Ancient Chinese states

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Ancient Chinese states (traditional Chinese: 諸侯國; simplified Chinese: 诸侯国; pinyin: Zhūhóu guó) were dynastic polities of China within and without the Zhou cultural sphere prior to Qin's wars of unification. They ranged in size from large estates, to city-states to much vaster territories with multiple population centers. Many of these submitted to royal authority, but many did not—even those that shared the same culture and ancestral temple surname as the ruling house. Prior to the Zhou conquest of Shang, the first of these ancient states were already extant as units of the preceding Shang dynasty, Predynastic Zhou, or polities of other cultural groups. Once the Zhou had established themselves, they made grants of land and relative local autonomy to kinfolk in return for military support and tributes, under a system known as fengjian.

The rulers of the states were collectively the zhuhou (諸侯; 诸侯; zhūhóu; 'many lords'). Over the course of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE), the ties of family between the states attenuated, the power of the central government waned, and the states grew more autonomous. Some regional rulers granted subunits of their own territory to ministerial lineages who eventually eclipsed them in power and in some cases usurped them. Over time generally the smaller polities were absorbed by the larger ones, either by force or willing submission, until only one remained: Qin (秦), which unified the realm in 221 BCE and became China's first imperial dynasty.

Background[edit]

The Zhou dynasty grew out of a predynastic polity with its own existing power structure, primarily organized as a set of culturally affiliated kinship groups. The defining characteristics of a noble were their ancestral temple surname (姓; xíng), their lineage line within that ancestral surname, and seniority within that lineage line.[1]

Shortly after the Zhou conquest of Shang (1046 or 1045 BCE), the immediate goal of the nascent dynasty was to consolidate its power over its newly expanded geographical range, especially in light of the Rebellion of the Three Guards following the death of the conquering King Wu of Zhou. To this end, royal relatives were granted lands outside the old Zhou homeland, and given relatively sovereign authority over those spaces.[2]

The Zhou government thus had multiple dimensions of relationship with different sorts of powerful men. The lineage elders of the old homelands were related to the royal house mostly through the pre-existing kinship structure, and not all were politically subservient.[3] The regional lords were established to provide a screen to the royal lands and exert control over culturally distinct polities and were mostly defined by that responsibility, but this was also embedded in the kinship groups. Some few high government ministers had special, non-hereditary titles of nobility. Lastly, there were the leaders of polities outside the Zhou cultural sphere.[4]

History[edit]

Shang Dynasty[edit]

Fang States (Chinese:⽅) refer to the various tribes and states during the Shang Dynasty in ancient China. Today, scholars' understanding of these states primarily comes from oracle bone inscriptions unearthed from the late Shang Dynasty Yinxu. In these inscriptions, these tribal states are often referred to as name + "方". In modern style Chinese the term can be duplicated to Fang Guo (Traditional Chinese:⽅國).

Western Zhou[edit]

Following the overthrow of the Shang dynasty in 1046 BCE, the early kings made hereditary land grants to various relatives and descendants.[5]: 57 Along with the land and title came a responsibility to support the Zhou king during an emergency and to pay ritual homage to the Zhou ancestors. In the Yellow River valley, of the earliest vassal states, the state of Cai (蔡) was founded following a grant of land by the conquering King Wu of Zhou to a younger brother. Other states established at this time included Cao (曹), Yan (燕), Jin (晉), and Chen (陳). The state of Song (宋) was permitted to be retained by the nobility of the defeated Shang dynasty, in what would become a custom known as Er Wang San Ke. In the Zhou heartland of the Wei River valley, most existing polities submitted to Zhou overlordship, although the state of Yu (虞) did not, since their rulers belonged to a more senior branch of the lineage group than the Zhou kings. The rulers of the state of Guo (虢) also belonged to a different branch lineage, but they submitted to royal authority.[3] The relation of the polities in the old Zhou heartland to the royal court was informed by the preexisting kinship structures amongst them, whereas the relationship between the newly established regional states and the royal court was more directly political.[6]

On the periphery, the states of Yan, Qi (齊), and Jin in the north and northeast had more room to expand and grew into large states.[7] In the southwest the non-Zhou state of Chu (楚) demanded attention. In the southeast, the Zhou confederation was bordered by the peoples of Wu (吳) and Yue (越). These polities and cultural outgroups in the Yangtze River valley were not fully incorporated into a centralised political domain until the imperial era.[8] Around the borders of the Central States (中國) lived "barbarians", fenced off from the Zhou heartlands by their enfeoffed regional lords. Apart from their responsibilities to the throne, the regional lords were responsible for their families, their people, and the altars of soil and grain outside their cities, where annual sacrifices were performed.

Over time the parcels of land the royal court was able to grant became increasingly small, and population growth and associated socioeconomic pressures strained the Zhou confederation and the power of the central government. Canny clans formed alliances through marriage, powerful ministers began to overshadow the kings, and eventually a succession crisis brought an end to the Western Zhou period.

Spring and Autumn period[edit]

After an attack by Quanrong nomads allied with several vassal states including Shen (申) and Zheng (鄭) in 771 BCE, the Zhou ruler King You was killed in his palace at Haojing. His son fled east and was enthroned by several vassal leaders as King Ping of Zhou. Traditionally, the flight to the east and establishment of the new king is written as if it proceeded very rapidly, but excavated manuscripts hold clues that a parallel king may have reigned for over twenty years, and there may have been no recognized king for nine years.[9][10] The scale of the division of loyalties between the regional states, and the effect it had on society is not clear, but archaeology attests significant movement of people around this time.[11]

With the primary capital moved from Haojing to Luoyi, after a succession crisis of indeterminate severity, the royal house had lost its power and almost all of its land. The prestige of the king, as Heaven's eldest son, was not significantly diminished, and he retained his ritual authority within the Ji lineage, but he and his family were much more reliant on the regional states.[12] Conversely, the rulers of the states had much less use for the king and his court. Whole lineage groups had moved around under socioeconomic stress, border groups not associated with the Zhou culture gained in power and sophistication, and the geopolitical situation demanded increased contact and communication.[11]

The regional states, now operating more autonomously than ever, had to invent ways to interact diplomatically, and they began to systematize a set of ranks amongst them, meet for interstate conferences, build great walls of rammed earth, and absorb one another.

Hegemons[edit]

As the power of the Zhou kings weakened, the Spring and Autumn period saw the emergence of hegemon-protectors (霸; Bà)[13] who protected the royal house and gave tribute to the king's court, while underwriting the remainder of the confederation with their military might. First among equals, they held power over all other states to raise armies and attack mutual enemies, and extracted tribute from their peers. Meetings were held between the current hegemon and the rulers of the states where ritual ceremonies took place that included swearing of oaths of allegiance to the current Zhou king and to each other. The first hegemon was Duke Huan of Qi (r. 685–643). With the help of his prime minister, Guan Zhong, Duke Huan reformed Qi to centralize its power structure. The state consisted of 15 "townships" (縣) with the duke and two senior ministers each in charge of five; military functions were also united with civil ones. These and related reforms provided the state, already powerful from control of trade crossroads, with a greater ability to mobilize resources than the more loosely organized states.[14]

By 667, Qi had clearly shown its economic and military predominance, and Duke Huan assembled the leaders of Lu, Song, Chen, and Zheng, who elected him as their leader. Soon after, King Hui of Zhou conferred the title of bà (hegemon), giving Duke Huan royal authority in military ventures.[15][16]

Between c. 600 BCE and c. 500 BCE a four-way balance of power emerged between Qin in the west, Jin in the north-center, Chu in the south, and Qi in the east whilst a number of smaller states continued to exist between Jin and Qi. The state of Deng (鄧) was overthrown by Chu in 678 BCE followed by Qin's annexation of Hua (滑) in 627 BCE, establishing a pattern that would gradually see all smaller states eliminated. Towards the end of the Spring and Autumn period wars between states became increasingly common.

Partition of Jin[edit]

Regional lords had begun the practice of granting lands of their own to powerful ministerial lineages. Over generations, in some places these ministerial lineages had grown more powerful than their lords. Eventually the dukes of Lu, Jin, Zheng, Wey and Qi would all become figureheads to powerful aristocratic families.[17]

In the case of Jin, the shift happened in 588 when the army was split into six independent divisions, each dominated by a separate noble family: Zhi (智), Zhao (趙), Han (韓), Wei (魏), Fan (范), and Zhonghang (中行). The heads of the six families were conferred the titles of viscounts and made ministers,[18] each heading one of the six departments of Zhou dynasty government.[19] From this point on, historians refer to "The Six Ministers" as the true power brokers of Jin.

The same happened to Lu in 562, when the Three Huan divided the army into three parts and established their own separate spheres of influence. The heads of the three families were always among the department heads of Lu. In Jin, a full-scale civil war between 497 and 453 BCE ended with the elimination of most noble lines; the remaining aristocratic families divided Jin into three successor states: Han (韓), Wei (魏), and Zhao (趙).[20]

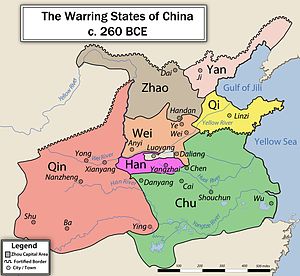

Warring States period[edit]

As the powerful states absorbed more of their neighbours, so too did they centralize their internal power, increasing bureaucratization and reducing the power of the local aristocracy. A new class of gentlemen-scholars, distantly related to the aristocracy but part of the elite culture nonetheless, formed the basis of this extended bureaucracy, their goal of upward social mobility expressed through participation in officialdom.

By about 300 BCE, only seven main states remained: Chu, Han, Qi, Qin, Yan, Wei and Zhao. Some of these built rammed earth walls along their frontiers to protect themselves both from the other states and raids by nomadic tribes like the Quanrong and Xiongnu. Smaller states like Zheng and Song were absorbed by their more powerful neighbors. The non-Zhou states of Ba (巴) and Shu (蜀) were both conquered by Qin by 316 BCE. All the other states gradually followed suit until Zhou rule finally collapsed in 256 BCE. Against this backdrop, polities also continued to emerge, as in the case of Zhongshan (中山) in the north, which was established by the nomadic Bai Di (白翟) in the 400s BCE and would last until 295 BCE.

Imperial era[edit]

Qin dynasty[edit]

Following Qin's wars of unification, the first emperor Qin Shi Huang eliminated noble titles which did not conform to his ideals of governance,[a] emphasizing merit over than the privileges of birth. He forced all the conquered leaders to attend the capital where he seized their states and turned them into administrative districts classified as either commanderies or counties depending on their size. The officials who ran the new districts were selected on merit rather than by family connections.

Han dynasty[edit]

In the early years of the Han dynasty, the commanderies established during the Qin dynasty once more became vassal states in all but name. Emperor Gaozu (r. 202–195 BCE) granted virtually autonomous territories to his relatives and a few generals with military prowess. Over time these vassal states grew powerful and presented a threat to the ruler. Eventually, during the reign of Emperor Jing (r. 156–141 BCE), his political advisor Chao Cuo recommended the abolition of all fiefdoms, a policy that led in 154 BCE to the Rebellion of the Seven States. The Prince of Wu Liu Bi (劉濞) revolted first and was followed by the rulers of six further states. The rebellion continued for three months until it was finally quelled. Later, Emperor Wu further weakened the power of the vassal states by eliminating many fiefdoms and restoring central control over their prefectures and counties.

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Modern scholarship has begun to move away from terms like "Legalism", especially when projected anachronistically into a time prior to their classification by Sima Tan, as in the case of Qin Shi Huang.[21]: 465 Nylan, writing in 2007, employs the term "Realpolitik".[22] Vogelsang, devoting a 2016 paper to the subject of terms used to name ideas in this philosophy, proposes the similar "political realism".[23]: 65 Kern's 2000 monograph on Qin Shi Huang's political thought opts against providing a simple definition.[24]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Chun 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Li 2008b, pp. 33, 43–44.

- ^ a b Khayutina 2014, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Li 2008a, p. 114.

- ^ Keay, John (2009). China – A History. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-722178-3.

- ^ Khayutina 2014, p. 41.

- ^ "Chinese History – Zhou Dynasty". ChinaKnowledge.de. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Mark Edward (2008). "The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han". In Brook, Timothy (ed.). History of Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9. p. 39

- ^ Chen and Pines 2018, pp. 10–14.

- ^ Milburn 2016, p. 70.

- ^ a b Li 2008a, pp. 120–123.

- ^ Pines 2004, p. 23.

- ^ "The Zhou Dynasty". Chinese Civilisation Centre, City University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ Hsu 1999, pp. 553–54.

- ^ Hsu 1999, p. 555.

- ^ Lewis 2000, pp. 366, 369.

- ^ Pines 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Sima Qian; Sima Tan (1959) [90s BCE]. "39: 晉世家". Records of the Grand Historian 史記. Zhonghua Shuju.

- ^ Rites of Zhou

- ^ Hui 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Davidson, Steven C. (2002). "Review: "Martin Kern. The Stele Inscriptions of Ch'in Shih-huang: Text and Ritual in Early Chinese Imperial Representation. American Oriental Series, vol. 85"". China Review International. 9 (2). University of Hawai'i Press: 465–473. JSTOR 23732133.

- ^ Nylan, Michael (2007). ""Empire" in the Classical Era in China (304 BC–AD 316)". Oriens Extremus. 46. Harrassowitz Verlag: 48–83. JSTOR 24047664.

- ^ Vogelsang, Kai (2016). "Getting the terms right". Oriens Extremus. 55. Harrassowitz Verlag: 39–72. JSTOR 26402199.

- ^ Kern, Martin (2000). The Stele Inscriptions of Ch'in Shih-huang: Text and Ritual in Early Chinese Imperial Representation. American Oriental Series. Vol. 85. New Haven: American Oriental Society. ISBN 0-940490-15-3. Cited in Davidson (2002).

Sources[edit]

- Chen Minzhen (陳民鎮); Pines, Yuri (2018). "Where is King Ping? The History and Historiography of the Zhou Dynasty's Eastward Relocation". Asia Major. 31 (1). Academica Sinica: 1–27. JSTOR 26571325.

- Chun, Allen J. (1990). "Conceptions of Kinship and Kingship in Classical Chou China". T'oung Pao. 76 (1/3). Leiden: Brill: 16–48. JSTOR 4528471.

- Hui, Victoria Tin-bor (2004), "Toward a dynamic theory of international politics: Insights from comparing ancient China and early modern Europe", International Organization, 58 (1): 175–205, doi:10.1017/s0020818304581067, S2CID 154664114

- Khayutina, Maria (2014). "Marital alliances and affinal relatives (sheng 甥 and 婚購) in the society and politics of Zhou China in the light of bronze inscriptions". Early China. 37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 39–99. JSTOR 24392462.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2000), "The City-State in Spring-and-Autumn China", in Hansen, Mogens Herman (ed.), A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures: An Investigation, vol. 21, Copenhagen: The Royal Danish Society of Arts and Letters, pp. 359–74, ISBN 9788778761774

- Li Feng (2008a). "Transmitting Antiquity: The Origin and Paradigmization of the "Five Ranks"". In Kuhn, Dieter; Stahl, Helga (eds.). Perceptions of Antiquity in Chinese Civilization. Würzberg: Würzburger Sinologische Schriften. pp. 103–134.

- Li Feng (2008b). Bureaucracy and the State in Early China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88447-1.

- Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L, eds. (1999), The Cambridge History of Ancient China: from the origins of civilization to 221 BC, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521470308

- Hsu, Cho-yun. "The Spring and Autumn Period". In Cambridge History of Ancient China (1999), pp. 545–586.

- Milburn, Olivia (2016). "The Xinian: an ancient historical text from the Qinghua University collection of bamboo books". Early China. 39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 53–109. JSTOR 44075753.

- Pines, Yuri (2002), Foundations of Confucian Thought: Intellectual Life in the Chunqiu Period (722–453 BCE), University of Hawai'i Press

- Pines, Yuri (2004). "The question of interpretation: Qin history in light of new epigraphic sources". Early China. 29. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 1–44. JSTOR 23354539.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

Media related to Ancient Chinese states at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ancient Chinese states at Wikimedia Commons