Scissor grinder

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

A scissor grinder (German: Scherenschleifer), sometimes also scissor and knife grinder or knife and scissor grinder, for short also knife grinder, is a craftsman who sharpens and repairs blunt knives, scissors and other cutting tools. It is an apprenticeship profession that nevertheless requires much experience.

Wandering knife and scissors sharpeners, also known as itinerant sharpeners or, more antiquatedly, cart sharpeners, have existed in Europe since the Middle Ages. Traditionally, they came from a few regions of origin in northern Italy and northwestern Spain. In addition, the itinerant craft was practiced by the so-called traveling people, including Sinti and Roma, and is one of the traditional occupations of the Yenish, especially in Central and Western Europe. They moved through the towns and offered sharpening and sharpening knives and scissors. In the second half of the 20th century, the demand declined sharply and almost came to a standstill. Thus, demand increasingly diminished as cutlery was used less overall in the domestic sphere as a result of the decline in general agricultural activity and the changing supply and buying patterns of food and textiles. The main reason for the lack of demand, however, was the fall in the price of new goods due to the emergence of mass production in cutlery.

In the meantime, the profession of knife and scissors grinders is rarely practiced and is thus one of the crafts threatened with extinction. In addition, professional sharpening tools are increasingly available commercially for household and commercial use. Since the end of the 20th century, the reduced general need for re-sharpening dulled knives and scissors has been served mostly by a dwindling number of mobile small entrepreneurs, some of whom move around nationwide, as an itinerant trade, and by various stationary specialized businesses, some of which are dispatched by mail.

Meanwhile, there is still continuous demand from some industries and professional groups, such as the catering, slaughterhouses and hairdressing salons, as well as more demanding hobby chefs, who often use high-quality and usually very expensive cutting tools. In addition to the specialized trade, a number of stationary and mobile sharpening and grinding services have thus developed since the end of the 20th century, most of which offer specialized services.

History[edit]

Emergence of the itinerant trade and grinding technology[edit]

With the increasing demand for cutting and thrusting weapons, the scissor and knife grinder emerged from the armorer's trade around 1500. The name comes from his task of grinding a pair of scissor blades to fit. During the production of swords and daggers, etc., they had to be sharpened several times, which was often done by specialized assistants of the armorer. When, in addition to weapons, "good scissors and knives" were increasingly needed by various crafts and were also in demand in private households, the craft of the cutler developed in the 16th century. Subsequently, the increasing qualitative and quantitative demands on the products led to a further division of labor in the form of splitting up the manufacturing process and new occupational groups emerged, such as the blacksmith, heat treating, grinders, sword sweepers and later the reiders. In particular, the "cutlery knife" went from being a special utensil of the nobility to an important everyday item for a broad section of the population. In addition, there was a general increase in the demand for cutlery and scissors, as well as fly cutter, billhook and other cutting tools. As with the armorers, a decentralized method of production prevailed among the knifemakers, which was provided by "mostly independent small masters with their own workshops."[1][2]

As a result of the wider distribution and use of knives and scissors, the need arose to resharpen cutting tools that had become dull through use. In the case of both knives and scissors, the blades wear out depending on the type and duration of use, in that the sharp edges are initially bent to the side in the minimal range during use, and subsequently torn out and become chipped, which makes recurring sharpening or re-sharpening necessary. This gave rise to the itinerant trade of the knife and scissors sharpener, who moved across the country and through the cities with his standard equipment, usually a grinding wheel, offering and providing resharpening.[1][3]

Saint Catherine of Alexandria is considered the patron saint of scissors cutters, as she is for armorers, among others.

The principle of grinding or (re)sharpening is always the same: The blade, such as of a pair of scissors, is moved lengthwise over an even harder surface, a grinding wheel. The heat generated in the process must be dissipated, if necessary, so that the steel of the sharpened material does not lose its hardness, which is already the case at temperatures above 170 °C. The thin cutting edges of knife blades, such as those of a pair of scissors, are always ground lengthwise. The thin cutting edges of knife blades are particularly susceptible. The simplest device, which can still be seen in folklore museums, is a mobile, elongated and open water box, into which the round whetstone protrudes halfway from the top. This is cranked over with the foot or the left hand, while the right hand guides the sharpening material. The water serves to cool the grinding wheel and thus the sharpening material. Rather rarely, the hand crank or (foot) pedal drive was operated by a second person.[4]

Soon, the grinding wheel was cooled mainly by means of a storage and drip container with an adjustable outlet tap mounted above the wheel, from which the grinding wheel was wetted with water (or sometimes also with grinding oil). In addition to the improved controllability, this had the advantage of reducing the weight for transportable grinding racks or for the later grinding carts.

→ See, for example, the corresponding device in the illustrated woodcut "Der Schleyffer" by Jost Amman from his "Ständebuch," c. 1568.

Cart grinders, Moleti, Arrotini, Afiladores[edit]

As a result of the emerging demand, scissors grinders began offering their services as itinerant craftsmen in the 17th century. In the beginning, they usually used a portable grinding frame with the grinding wheel, which they carried on their backs. Partly, however, they also used the larger grinding wheels that were usually available in settlements and remote farms, etc., and thus offered only their skill as knife and scissors sharpeners.[1]

From the end of the 17th century, the transportable grinding frame was predominantly replaced by the more robust grinding cart and so-called cart grinders moved from place to place. In the course of further technical developments, differently constructed sander carts or sander carts were created in Europe and the Near East, such as the "Austrian sander", which was widely used in Central Europe. With the end of the First World War in 1918 and "with the industrial production of cutlery, the trade of the cart grinder died out."[5]

The wandering craftsmen often came from the then Welschtirol (later: Trentino) and belonged mainly to a few families from the high valley Val Rendena – also called Valle dei Moleti (German: Tal der Messerschleifer) – north of Riva del Garda. As so-called "Moleta" they spread the scissors sharpening craft not only throughout Europe, but also in the US and many other countries of the world. In addition to the seasonal or year-long migration of the men from the Val di Fassa, many of them emigrated permanently and became residents abroad.[5][6]

Another region of origin was the Résia in Friuli, Italy, where there was (also) too little work and the men traveled as scissor grinders, so-called "Arrotini," throughout Europe and especially through the former lands of Austria-Hungary to ensure the survival of their families. The typical grinding carts of the Arrotini were replaced in the 1960s by converted bicycles with the grinding wheel permanently mounted between the handlebars and the saddle. After jacking up the rear wheel with a fold-down or separate stand, which also makes the jacked-up wheel stable, the grinding wheel can be driven by the normal pedals via a belt or separate chain. In more recent times, motorization took place through the use of motor-driven implements and appropriately converted motor vehicles. In the meantime, this itinerant craft has ceased to be important.[7]

- Cart grinders, Moleti, Emigrants, Arrotini, Afiladores

- Cart grinder, c. 1650 (etching by Adriaen van Ostade)

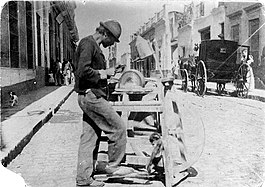

- Scissors grinder ("Afilador") with grinding cart in Buenos Aires, 1870

- Scissors grinder ("Afilador") with grinding cart in Oviedo in Spain, about the beginning of the 20th century.

- Typical "scissor grinder" bicycle of the Italian "Arrotini" from the 1960s, here with jacked up rear wheel

- "Afilador" with converted "scissors grinder bicycle" in Spain, 20th c.

In the rural Spanish region of Galicia, the tradition of scissors sharpeners can be traced back to the late 17th century. The so-called "Afiladores" came mainly from various towns in the north of the local province of Ourense and left their cultural imprint there. Thus, they developed their own cant, the barallete, which was based on the Galician language and enriched it with a mixture of technical knowledge and the itinerant craft of the Galician scissors grinders. The original tool of the afiladores was a rack with the grinding wheel, which they carried on their backs. Later it became a grinding cart that was pushed, then an adapted "scissors grinder's bicycle" as in the Italian Arrotini, and finally it was partly motorized. Meanwhile, the trade of afiladores also lost its importance.[8][9][10]

Wandering craftsmen, scissors grinders from the traveling people[edit]

Travelling merchants and craftsmen have been found in Europe since the Middle Ages, mainly Jews and Sinti and Roma. The reason for this was their social exclusion: they were not allowed to settle as craftsmen in the cities and were not accepted into the guilds. Thus, they earned their living as traveling merchants, peddlers, tinkers, scissor grinders or actors and artists. In the urban societies they sold goods that were often not offered by the urban merchants. As craftsmen, their trades – such as that of the scissors grinder – covered a niche in urban crafts, which on the one hand required a certain level of skill, but on the other hand was also not sufficient for subsistence in the city. In rural society, itinerant craftsmen and peddlers were important for their supply and satisfaction of needs until the middle of the 20th century.[11][12]

In addition to the journeymen and the seasonal migrant workers, such as the so-called Hollandgänger, the permanent migration of social fringe groups, who moved as vagrants and beggars through the rural areas or lived from trade or small crafts as peddlers, scissor grinders and tinkers, was one of the phenomena of the 18th and 19th centuries. According to the Westphalian State Museum of Art & Cultural History director Willi Kulke, the number of itinerant craftsmen was far greater than the historical account would indicate at the beginning of the 21st century, because written records are more than inadequate for these occupations in particular. Due to the low earning opportunities and competition from other merchants and craftsmen, they were often forced to constantly expand their wandering radius. Consequently, they had to live on the streets for longer periods of time and also ask for alms when their earnings were poor. The transition to a vagabond lifestyle was fluid. The permanent life of itinerant artisans on the road led to many prejudices and rumors, with them often being considered "morally depraved and suspected of theft" among their contemporaries.[11][12]

The everyday life of the traveling merchants and craftsmen was characterized by their difficult way of life. In addition, they were subject to constant regulations and legal restrictions, "which were intended to make their lives as difficult as possible and ideally to drive them out of the country.[13] In the beginning, the authorities issued so-called trading patents - sometimes also referred to as passes or carte blanche - to peddlers in particular, which can be seen as the forerunner of the later itinerant trade license. Such regulations by the authorities existed not only in all parts of Germany, but also in many countries of Central and Western Europe.[11]

The traveling merchants and craftsmen transported their goods or implements and tools under their own power, with a wheelbarrow or handcart, with a backpack basket or a vendor's tray. Owning a dog team or a horse-drawn vehicle was considered a social advancement. The typical wheelbarrows of the wandering scissors grinders usually had only one wheel, which served both as a drive wheel (flywheel) for the grinding wheel and for transporting the wheelbarrow. For his sharpening and grinding work, the scissors grinder stepped behind the machine, placed the leather drive belt over the flywheel, and drove the grinding wheel. Most wheelbarrows were equipped with only one grinding wheel – only better equipped scissors grinders could switch from one or sometimes several grinding wheels to a polishing wheel.[11]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Yenish, who came from the rural poor classes in Tyrol, Switzerland and southern Germany, began to migrate and, as a traditional fringe group of society, practiced occupations similar to those of the ethnic minorities of the Roma and Sinti: "basket maker, ragpickers and [in particular also] scissors grinders". The latter occupational group became the typical appearance of the members of the traveling people, who primarily roamed from spring to fall, due to the grinding tools they carried with them, the grinding cart. Generalizing, the sedentary population in the German-speaking area referred to these "Travellers" as well as the entirety of the Roma, Sinti and Jenische as Gypsies until modern times.[11][14]

Between increasing exclusion and meeting needs[edit]

Toward the end of the 19th century in the German Empire, the Verein für Socialpolitik (Association for Social Policy) took up the incipient social discussion about the expanding trade of itinerant merchants and craftsmen and produced an extensive study. However, the focus was on the economic aspects, such as the complaints of merchants and craftsmen or their associations about "the allegedly business-damaging competition of peddlers," while the social issues of their activity were neglected. In 1898/99, the Verein für Socialpolitik published its findings under the title Untersuchungen über die Lage des Hausiergewerbes in Deutschland (Studies on the Situation of the Peddling Trade in Germany) in five volumes, in which the association described in detail, among other things, both the negative contemporary opinion of the lives of itinerant merchants and craftsmen and the increasing state sanctions and regulations, such as the restrictive issuance of itinerant trade licenses.[15] Meanwhile, however, the Verein für Socialpolitik also found in its report, "The pan-menders, basket-makers, scissor-grinders [...] belong in part to the Gypsies, but on the whole they are already of a different kind and already form a more solid group of the wandering people, since they at least carry on useful trades and were more confined in their journeys to certain areas."[16][17]

In the 1920s and into the 1930s, there was once again an increase in the number of scissor grinders and peddlers: the Great Depression and mass unemployment forced people to earn a living with petty trade or auxiliary craft activities "on the streets. While peddlers were again more numerous in rural areas, itinerant workers such as scissor grinders in particular offered their services in urban areas.[17]

In Germany, from the beginning of the 19th century until the Porajmos in the Nazi era, there were often campsites of the traveling people in regions with a corresponding need for recurring crafts and maintenance work such as re-sharpening cutting tools. The craftsmen performing contract work did not have a workshop, but the work was carried out at the customers' premises. This included, in particular, scissors grinders, who, for example, regularly found work in the Swabian Alb region with its once traditionally large number of textile factories. The scissors were reground and tested on site. Such a storage place for Sinti and Roma caravans existed, for example, in the Zollernalbkreis in the then village of Steinhofen, with an inn in neighboring Bisingen serving as the registration place for the necessary trade licenses.[18][19]

Although the racially motivated persecution of the itinerant people by the Nazi Germany ended with the Second World War, exclusion and a lack of social participation continued in the German successor states. In this respect, the wandering scissor grinders and other itinerant craftsmen who reappeared in the postwar period and with the onset of the economic miracle continued to be met with prejudice and discriminated against as "gypsies."[20]

- Wandering craftsmen, scissors grinders from the traveling people

- Roma/scissors grinder "Old Lovell" in England, 1885

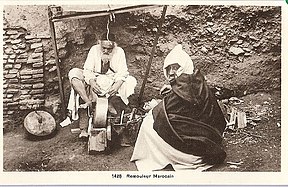

- Jewish scissors grinder in Morocco, between 1900 and 1920

- "Travelling" scissors grinder with grinding cart in Marseille, early 20th c.

- Scissors grinder with grinding cart in Vienna, around 1905-1914

- Yenish scissors grinder in Switzerland, c. 1930

- Scissors grinder with "Dutch grinding cart" in Amsterdam, c. 1930

- Scissors grinder in the Netherlands, 1931

Travel routes and territories[edit]

As a rule, there were no agreements on travel routes and "territories" among the wandering scissors cutters, especially since there were no associations such as guilds or federations.[1] Only within the itinerant craftsmen from the same region of origin in Welschtirol, Italy and Spain or from the same ethnic group affiliation and "home region" of the traveling people, there were partly informal agreements or there were partly traditional territorial claims.[21] Thus, the Afiladores from Galicia traveled mainly throughout Spain and neighboring Portugal, while the "Moleta" from Welschtirol and the "Arrotini" from Friuli in Italy traveled to certain European countries as well as many other countries throughout the world. In doing so, they often covered enormous travel routes and were sometimes on the road for years.

In the rural areas they frequented, they often met competition from local small craftsmen who themselves sought their livelihood as itinerant craftsmen and offered their services in their local or regional environment. For the supra-regional itinerant scissors grinders from the special regions of origin or from the itinerant people, this had the consequence that the expected demand and earnings were often not assessable due to the local and regional competition – and in the end always changes of the actually planned travel route had to be made as well as longer intermediate distances had to be mastered without any possibility of earning money.[1]

Decline of itinerant trade in modern times[edit]

In many countries of Western and Central Europe, including Germany, traveling scissor grinders still came "at regular intervals to residential streets to offer their services in households and sharpen scissors and knives as needed" until the second half of the 20th century. From the 1950s to the 1970s, however, modern mass production and a wider supply of consumer goods made the purchase of scissors and knives so inexpensive that it was often more cost effective to replace the aging cutting tools with cheap products. In addition, the change in the world of work as a result of the post-war boom (Economic miracle) led to a sharp decline in general agricultural activity, so that maintaining the sharpness of the cutting tools used in this area increasingly took a back seat. At the same time, average private households increasingly supplied themselves with both partially and fully prepared foodstuffs and ready-made textiles, so that the private use of cutting tools generally declined and resulted in a reduced need for resharpening by scissor sharpeners. Furthermore, this development was accelerated by the emergence of DIY stores and the availability of affordable sharpening tools and grinding machines. In the meantime, professional sharpening tools such as manual or electrically driven blade sharpeners are increasingly available commercially for household and commercial use. Meanwhile, home improvement tools with a "scissors program" only resharpen the top of scissors without disassembling them, whereas professional scissor sharpeners usually disassemble scissors and resharpen both cutting surfaces.[1][3][22][23]

As a result of the lack of demand, regular visits by scissor grinders initially declined[24] and eventually ended almost entirely.[1][3][22]

In addition, the industry has fallen into disrepute due to fraudulent "scissor grinders" going from house to house in many places, who deliberately seek to take advantage of their customers by providing inferior and overpriced services,[25] or are even bent on trick theft.[26][3][22][27] Due to the incorrect grinding technique and/or insufficient cooling often practiced by such "peddlers," the blade can "anneal," rendering "the sharpened object virtually useless."[28] In addition, the industry has also fallen into disrepute due to the fact that the "scissor grinders" have been known to use a variety of techniques.

Present[edit]

Development since the end of the 20th century[edit]

Since the end of the 20th century, scissor sharpeners have become increasingly rare, as only a few people still require their services. Exceptions to this are professional users such as hairdressers, chefs, butchers or tailors, who still count on high-quality – and often very expensive – cutting tools. These need to be expertly sharpened at regular intervals to ensure accurate and fatigue-free work. In addition, even "more demanding hobby chefs [...] are now willing to put a price on sharp knives."[3][22][29]

In Germany, scissors grinders belong to the occupational group of grinders, but unlike the tool grinder, which since the late 1980s has been called cutting tool mechanic, specializing in cutting machine and cutlery technology, or the scissors and cutlery sharpener, they are not an apprenticeship occupation, but only an apprentice occupation.[22] The related skilled trade occupation has been called precision tool mechanic since August 2018. The surgical mechanic manufactures scissors for medical purposes and also sharpens them.[30] In addition, "grinding and repair jobs [...] are now among the most common jobs performed by cutlers", which are also among the endangered crafts.[31] The occupation is called precision tool mechanic.

Similar to the scissors and cutlery sharpeners working in the production of cutlery – who can be found in Germany especially in the Bergisches Land region – the profession is characterized by "special demands" and requires a lot of skill and experience. The sharpening of scissors and cutting tools of many kinds "on the grinding machine requires a particularly good eye, excellent knowledge of materials, and a decidedly steady hand."[32] This is especially true for the resharpening of scissors, especially their insides (hollow sides), as well as scissors with curved scissor levers, such as surgical scissors or nail scissors, which requires both a great deal of experience and expertise, as well as special sharpening tools, such as flow discs.[33]

As in Germany, there is also no vocational training for knife and scissors sharpeners in Austria, Switzerland and Italy (South Tyrol), so that the necessary specialist knowledge and skills can only be acquired by "learning".[31] In addition, in Austria, as in other countries, the re-sharpening of cutting tools is part of the field of activity of the related, artisanal apprenticeship of the cutler; however, there has been no apprenticeship (training) for the cutler in Austria since the end of the 20th century.[34] In Switzerland, there is still a basic vocational training program for cutlers, but the craft is threatened with extinction.[35] In South Tyrol, there is no formalized training program for cutlers. For the related German apprenticeship occupation of precision tool mechanic, no comparable training program exists in Austria, Switzerland, and South Tyrol.[36]

Traveling, stationary and mobile grinding stores[edit]

Since the end of the 20th century, there has been a decreasing number of mobile scissor and knife sharpening stores in Germany – in addition to various stationary sharpening shops with at farmer markets and fairs, some of which are also mobile. They are mostly run as itinerant businesses by small entrepreneurs, with some of them also acting as itinerant traders and selling knives and scissors on the side.[3] The usual equipment of mobile grinding workshops, which are usually housed in small workshop trailers or trucks, includes above all electric grinding machines with "coarse and fine-textured grindstone[s]" as well as special "serrated blade-stone[s]" which, among other things, "help frequently used hairdressing scissors blades to achieve their original sharpness". In addition to conventional cooling with water or grinding oil, grinding is now partly "oil-based", using oil-soaked diamond grindstones. The water or oil that evaporates during grinding provides cooling for the grinding wheel and the sharpening material. After grinding, the sharpened material is usually polished using an electric polishing machine with special polishing wheels, such as those made of buck horn or sailcloth- fins.[22][28][29][37]

Particularly in the "blade city" of Solingen, the center of the German cutlery industry in the Bergisches Land region, and in Tuttlingen in Baden-Württemberg, with its large number of medical technology companies, there are a number of stationary grinding companies that send reground knives and scissors (Solingen) or reground surgical scissors etc. (Tuttlingen) by mail. (Tuttlingen) are sent by mail.[38] In contrast, many of the still existing, mostly medium-sized companies in the clothing and textile industry in Germany, such as in the Swabian Alb region, are regularly visited by scissor grinders who do their work on site until the present day (2020). In addition, there are some "travel grinders" who offer their services nationwide on fixed dates at retail outlets such as home and metal goods stores, as well as at consumer fairs.[39]

In the Austrian-Italian region of Tyrol, several scissor grinders were still circulating by small truck around 2015.[40]

In southern and southeastern Europe, towards the end of the 20th century, instead of the "scissor-grinder bicycles" of the Arrotini, partly converted motor scooters or mopeds came into use, and ultimately also three-wheeled panel vans through to vans and small trucks, in which one or more grinding wheels – mounted on the motorcycle or in the superstructure of the commercial vehicle – are connected to the transmission shaft of the engine, or in some cases are also operated electrically.[7] In the end, the "scissor-grinder bicycles" of the Arrotini were replaced by the "scissor-grinder bicycles" of the Arrotini.

Similar developments in the industry have taken place and are taking place in many countries around the world. While in underdeveloped countries and regions some itinerant craftsmen still roam around with often very basic sharpening equipment up to the present day (2020), mobile scissors and knife sharpeners are currently mostly on the move with converted bicycles or motorcycles or appropriately equipped vans or small trucks. Overall, however, their numbers have declined sharply in recent decades, especially in industrialized nations and emerging markets.[7][41]

In the countries of the Anglosphere, such as the British Isles (United Kingdom and Ireland), the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, a sharpening service stand is often a fixed feature of the traditional "farmers' markets" that take place there regularly, especially in rural areas. In most cases, this is a sharpening and grinding service based in the respective region, which can thus build up a regular customer. In these countries, the sharpening and grinding services often use so-called wet grinding machines with electric drive, in which a slowly rotating grinding wheel runs through a water bath on one side and is thus cooled. In addition, special belt grinders, also electrically operated, are often used. Such wet and belt grinders can also be found in some cases at sharpening and grinding services in Scandinavia, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and some other European countries; they are also widely used by other craft users.[41]

In addition, there are now a number of mobile sharpening and grinding services in Germany and many other countries that carry their mobile grinding equipment in vans and – "like their predecessors from the traveling public who once worked regionally for textile companies" – come to their customers on order, where they carry out their work directly on site. They often specialize in certain industries and also operate in a regionally limited area.[41]

The respective specialization is geared, for example, to commercial kitchens, hotels, restaurants and slaughterhouses (sharpening of cutting tools such as cooking tools, cutlery knives, slicer knives, cutter knives, meat grinder knives and meat grinder discs), hairdressing salons (sharpening of hairdressing scissors) or municipal green space offices, landscape contracting and forestry operations (sharpening of lawn mower knives such as spindle knives, undercutting knives and sickle knives, saw chains of chain saws as well as other gardening equipment). The main advantage for customers is that the cutting tools are immediately available again and any replacement equipment is not required if the tools are taken away from home. In addition, if the cutting performance is insufficient, reworking is usually carried out immediately (free of charge).[41]

In some cases, these mobile grinding services also offer special repair work or take on related additional services such as the dressing or grinding of cutting boards and chopping blocks made of plastic or wood, which is regularly required in catering and slaughterhouses, in accordance with the HACCP EC hygiene standard.

- Scissors grinder since the beginning of the 21st century

- Scissors grinder with a "modern grinding cart" in Paris, 2008

- Scissors grinder with converted bicycle in Rome, 2011

- Scissors grinder with converted scooter in Tossa de Mar, 2009

- Workshop trailer of mobile scissors grinding shop in Bremen, 2017.

- "Workshop small truck" of a mobile scissor grinding shop in New York City, 2010.

- Mobile sharpening service in Hampshire, 2019

Market situation towards the beginning of the 21st century[edit]

The trade of "itinerant" knife and scissors sharpeners is generally under increasing market pressure as a result of globalization. The relocation of mass production of cutlery to low-wage countries as well as marketing in global online trade or as promotional goods by discounters, department stores and furniture chains are causing a sustained and further drop in the price of new products, especially since the use of newer technologies in manufacturing and factory sharpening such as steel material selection and tempering, laser cutting and sharpening technology as well as ceramic coating of cutting surfaces lead to useful results and longer cutting durability. Thus, for the normal consumer with lower demands, the replacement of blunt cutting tools by new acquisition is now usually cheaper and also causes less effort than regular professional re-sharpening. In contrast, a few large and many long-established niche manufacturers for the professional needs of knives and other cutlery, which in Germany, for example, are mainly based in Solingen, have been able to hold their own in the market and have even been able to record sales growth since the end of the 2000s.[41][42]

Subsequently, the need for re-sharpening and regular basic sharpening of cutting tools on the part of professional users and more demanding hobby chefs will further encourage the evolution of the knife and scissors sharpening trade, which occurred in part at the end of the 20th century, toward specialized service providers.[41] The need to sharpen knives and scissors will continue to grow.

Reception[edit]

General[edit]

The figure of the scissor-grinder, the "stranger in the city" or in the town,[1] inspired not only the vernacular, but also many artists and cultural figures, such as painters, sculptors, authors, photographers, filmmakers, composers and musicians.

In everyday culture, moreover, the motif of the traditional scissors grinder with its typical grinding wheel can be found, among other things, in decorative objects, ornamental figures or toy items, such as:

- decorative porcelain sculpture (like from Meissen porcelain manufactory)

- rather rare decorative bronze (like as bronze figurine "Scissor grinder lighter" from Vienna around 1900, which shows a scissor grinder with grinding cart at work, where the grinding wheel serves as ignition surface for matches) or very rarely as ivory

- decorative carved wooden, sometimes as a Nativity scene

- historical tin toys (like from the former toy manufacturer Arnold from Nuremberg)

- tin figure or as part of tin figure groups

Currently (2020), various museums and exhibitions are dedicated to the historical life and work of itinerant knife and scissors sharpeners, showing, among other things, typical working tools, documents and photographs. In addition, in more recent times, in the former regions of origin of the "Moleta" and "Arrotini" in Italy and the "Afiladores" in Spain, some places of memory have been created, dedicated to the history of the scissors grinders with special museums, exhibitions, events and in the form of monuments.

→ See also the following subsection museums, exhibitions, memorials and monuments.

Scherenschleiferstraße in Lüneburg's old town is named after the trade of the scissor grinders.

Sayings, fairy tales, folk songs[edit]

The trade of the scissor grinder was often regarded in a derogatory manner in the past. Thus, up to the present day (2020), there exists in Swabian the name calling Scheraschleifer, which describes a good-for-nothing who is unreliable and cannot be trusted. Some of the wandering scissors grinders – among others also on the Swabian Alb with its once many textile businesses – with poor tools and sometimes incompetence (too high temperature of the abrasive material, disproportionate material removal) did not provide a sustainable sharpening performance, so that the knives and scissors quickly became dull again.[32][43][44]

Occasionally, scissors grinders used to have a trained monkey with them to attract an audience. This is where the cyclist's saying comes from: He's sitting there like a monkey on a grindstone – the animal, of course, never "sat" on the rotating stone, but kept jumping up and down with its rear end.[3]

In the fairy tale Hans in Luck by the Brothers Grimm, the scissors grinder is Hans' very last and poorest barter partner, and he also takes advantage of him.

The figure of the scissor-grinder is treated in various, mostly folk songs. A (bawdy) folk song that takes up the theme of the wandering men and is still sung in the present day (2020) in southern Germany at festivities or at many a later hour in the tavern is called Wir sind die Schleifer.[45] Otto Hausmann's folk poem Der Scherenschleifer[46] was set to music in 1890 by Robert Kratz (1852–1897) as a "Lied im Volkston für Männerchor" (Song in folk tone for male choir).[47] In Flanders, Jan Bois published in his 1897 collection of One Hundred Old Flemish Songs, among others, a well-known scissor-grinder song from the Leuven region, entitled Komt vrienden in het ronde.[48] It was later followed by a German translation (Kommt Freunde in die Runde).[49]

Art[edit]

In the visual arts, especially in painting, depictions of scissor grinders were a popular subject. Among the most famous works are:

- Scherenschleifer, c. 1568, woodcut by Jost Amman from the Ständebuch

- Der Scherenschleifer, c. 1650, etching by Adriaen van Ostade

- Der Scherenschleifer, 1808–1812, painting by Francisco de Goya

- Scherenschleifer, c. 1840, painting by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps

- Der Scherenschleifer, 1891, painting by Giovanni Giacometti

- Der Messerschleifer, 1907, painting by Jean-François Raffaëlli

- Der Messerschleifer, before 1913, painting by Carl Maria Seyppel

- Der Scherenschleifer, 1913, painting by Kazimir Severinovich Malevich

- Der Messerschleifer, 1926, woodcut by Todros Geller

- Scherenschleifer, 1936, painting by Felix Nussbaum

English sculptor Newbury Abbot Trent created several natural stone reliefs depicting historic London street scenes for Buchanan House in London, a high-rise building in the St. James's district of Westminster built in 1957. Among them is a relief depiction of a scissors grinder with his grinding cart at work, watched by a child.

Fiction[edit]

- Dino Larese: Der Scherenschleifer. Geschichte eines heitern Lebens. 5. Auflage. Huber, Frauenfeld 1995, ISBN 3-7193-0788-3(Larese erzählt in Form einer belletristischen Darstellung aus eigenen Erinnerungen über das harte Leben seines Vaters, der zeitlebens als Scherenschleifer „auf dem Seerücken vom Oberthurgau bis nach Stein am Rhein" von Ort zu Ort zog. First publication: 1981).

- Johannes Vilhelm Jensen: Hverrestens-Ajes – Anders med slibestenen. In: Ders.: Himmerlandshistorier, tredie Samling. Gyldendal, Kopenhagen 1910 (dänisch; als deutsche Übersetzung unter dem Titel Himmerlandsgeschichten in verschiedenen, teils eingeschränkten Ausgaben bei mehreren Verlagen erschienen. Der Literaturnobelpreisträger Jensen behandelt in der Erzählung das Schicksal eines armen Mannes aus dem Himmerland, der als Scherenschleifer umherzieht, damit seine Familie überlebt.).

- Eugène Chavette (1876) [1873], Der Scherenschleifer [Le rémouleur] (Roman (in vier Bänden)) (in French), Leipzig: Hartleben

Photographs[edit]

Photographs of scissor grinders in the Viennese streetscape from the period between 1905 and 1914 are known from the Austrian photographer Emil Mayer, who mainly documented Viennese street scenes and "types" photographically.

In 1939, German photojournalist Richard Peter portrayed a scissor grinder with his grinding cart as part of his worker photographs, portraying him as a self-confident and well-traveled craftsman. The series of five photographs taken in the Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) is now in the possession of the Deutsche Fotothek in Dresden.

The Deutsche Fotothek's holdings also include a documentary photograph of a scissor grinder in a Berlin backyard from 1967 by German photographer (and later RAF lawyer) Klaus Eschen.

Film[edit]

- L'Arrotino (2001; German "Der Scherenschleifer"), 35mm short film by Straub-Huillet.

- Under the Sky of Paris (1951; original title: Sous le ciel de Paris), French feature film directed by Julien Duvivier and starring Albert Malbert as the Scissors Grinder.

- Adieu Léonard (1943), French feature film directed by Pierre Prévert. The role of the scissor-grinder is represented by Guy Decomble.

- Regain (1937), French feature film directed by Marcel Pagnol based on a novel by Jean Giono. One of the main characters of the film is the scissors grinder Gédémus, played by Fernandel.

- Angèle (1934), French feature film by Marcel Pagnol based on a novel by Jean Giono. The role of the scissor-grinder Tonin was played by Charles Blavette.

- Liliom (1934), French feature film directed by Fritz Lang. Author, poet and actor Antonin Artaud plays the role of the scissor-grinder and guardian angel.

Music[edit]

In classical music, several composers dealt with the figure of the scissor-grinder, such as Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (1667–1737) in his baroque musical piece Le rémouleur.

Museums, exhibitions, memorials and monuments[edit]

About the historical itinerant profession of the knife and scissors sharpener inform various museums and exhibitions, such as in particular some folklore and local history museums, open-air museums, as well as working world, craft and industrial museums. Among the usual exhibits are typical work tools, such as portable grinding racks, grinding carts and the adapted "scissor grinder bicycles" of the Moleta, Arrotini and Afiladores, as well as documents and photographs. Such collections can be found, for example, in the following countries and museums (selection):

- Germany: at the German Agricultural Museum Schloss Blankenhain in Blankenhain in Saxony; at the German Museum in Munich; at the Historical Messerschmiede in Mössingen in Baden-Württemberg;[50] at the Hohenloher Freilandmuseum in Schwäbisch Hall-Wackershofen in Baden-Württemberg;[51][52] at the Elmshorn Industrial Museum in Elmshorn in Schleswig-Holstein;[53] at the decentralized LWL Industrial Museum in Westphalia-Lippe; at the Lower Rhine Open Air Museum in Grefrath in North Rhine-Westphalia.

- Netherlands: at the Ootmarsum Open-Air Museum in Ootmarsum in the province of Overijssel; at the Zuiderzee Museum in Enkhuizen in the province of North Holland

- Austria: in the Landstraße District Museum in Vienna; in the private "Historical Museum around Cutlery with Experience Grinding Shop" (established in the 2010s by Helmut and Waltraud Rief's grinding shop located in Hattingerberg in Tyrol).[54]

- Italy: in the Museo etnografico del Friuli in Udine in Friuli; see also below for places of remembrance, museums and monuments in the province of Trentino and in the Résia Valley in Friuli.

- Spain: in the Museo das Mariñas in Betanzos, in the province of A Coruña, in northwestern Galicia; see also below for memorials and monuments in the Galician province of Ourense.

- Australia: in the National Museum of Australia in the capital Canberra (on display is the Saw Doctor's wagon – mobile home and mobile grinding workshop of Harold Wright, with which he traveled through the northwest of Victoria and New South Wales in Australia from 1935 to 1969 together with his wife and daughter. The unique truck trailer has been in the possession of the National Museum of Australia since 2002 and, after restoration, is one of the "highlights" of the permanent exhibition).[55]

LWL Industry Museum – Westphalian State Museum of Industrial Culture, in its 2013 exhibition "Migrant Work. Man – Mobility – Migration. Historical and Modern Working Worlds", dealt with the phenomenon of labor migration. One of the total of 15 exhibition areas dealt with the historical migrant profession of knife and scissor sharpeners under the title "Scissor Sharpeners – Strangers in the City." Among the exhibits was an adapted "scissor grinder's bicycle." The special exhibition was shown from 2013 to 2015 at four different locations of the decentralized industrial museum in Westphalia and Lippe.[56] An exhibition catalog was published in 2013 as accompanying material.[1]

In the northern Italian province of Trentino, formerly known as Welschtirol, a monument in the Val Rendena high valley has been commemorating since 1969 the historical itinerant trade and labor migration of men from the valley who used to wander all over Europe as "Moleta" in search of work, some of whom emigrated to the US and many other countries around the world.[6] The monumental memorial is located in the Trentino village of Pinzolo and consists of a larger-than-life bronze sculpture on a solid block of natural stone. The sculpture was created by Italian sculptor and Franciscan Silvio Bottes and realistically depicts a scissor grinder sharpening knives on the typical pedal-powered grinder. The monument was financed by donations from many shear grinders who emigrated from Val Rendena from all over the world.[57] In 2018, an international meeting of knife and shear grinders was held in the village.[58] In the Trentino municipality of Cinte Tesino, a small grinder museum is dedicated to the former itinerant knife grinders from the village and their working and living conditions.[59] The monument is a work of art.

Another memorial site is located in the Résia Valley in Friuli, Italy, in the municipality of Resia in the district of Stolvizza, the "village of the Arrotini", the scissors grinders. The Museum of the Scissors Grinders, opened there in 1999, informs about the former itinerant craftsmen from the village and Val Resia, who used to travel all over Europe and especially through the countries of Austria-Hungary. A monument previously inaugurated in 1998, consisting of a large bronze bas-relief carved into a boulder, depicts an arrotini with his typical converted "scissor-grinder's bicycle" from the 1960s.[60][61][62] A Festa del arrotino, a "festival of the scissor-grinders", is celebrated annually in the village.[63] The museum is open to the public.

In the Spanish region of Galicia, in the province of Ourense, the itinerant trade of the scissors sharpeners who once came from this region, the afiladores, is honored, among other things, with a monument in the municipality of Nogueira de Ramuín. A life-size bronze sculpture, created by the Spanish sculptor Manuel García de Buciños, shows an afilador with his sharpening cart sharpening a knife. The sculpture stands on a high stone pedestal with gargoyles, amidst the water surface of a fountain.[10] Another monument to scissors sharpeners, also a bronze sculpture, stands in the municipality of Esgos, which is located near Ourense.[64]

Media[edit]

Literature[edit]

- Josh Donald: Sharp. The Definitive Introduction to Knives, Sharpening, and Cutting Techniques, with Recipes from Great Chefs. 1. Auflage. Abrams & Chronicle Books, London 2018, ISBN 978-1-4521-6306-2 (englisch).

- Marius, Mélanie Martin: Messer. Rezepte und Techniken. 1. Auflage. Callwey, München 2017, ISBN 978-3-7667-2282-9.

- Willi Kulke: Scherenschleifer – Fremde in der Stadt. In: LWL-Industriemuseum [Red.: Hendrik Bönisch] (Hrsg.): Wanderarbeit. Mensch – Mobilität – Migration. Historische und moderne Arbeitswelten. (Ausstellung im LWL-Industriemuseum Ziegeleimuseum Lage). 1. Auflage. Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1, S. 43–52 (Ausstellungskatalog).

- Thomas Blubacher: Wie es einst war. Schönes und Wissenswertes aus Großmutters Zeiten (= Insel-Taschenbuch. Nr. 4272). Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-35972-2 (Auszug in der Google-Buchsuche).

- Willy Römer: Vom alten Handwerk. Nagelschmiede, Scherenschleifer, Feilenhauer ... 1925–1931 (= Edition Photothek. Nr. 23). Nishen, Berlin 1988, ISBN 978-3-88940-223-3 (Bildband).

- Jost Amman, Hans Sachs: Das Ständebuch. Frankfurt am Main 1568 (Seitenwiedergabe bei Wikisource – Original title: Eygentliche Beschreibung aller Stände auff Erden. 114 Holzschnitte von Jost Amman mit Versen von Hans Sachs).

Television[edit]

- Einer der letzten seiner Art: Der mobile Messer- und Scherenschleifer Marco Sala. Franken Fernsehen, April 18, 2018 (2:51 minutes)

- Angelo Schmid – Mobiler Messerschleifer. ORF 2, Sendereihe heute konkret, May 25, 2015 (3:28 minutes)

- Der Scherenschleifer – Überleben auf Messers Schneide. SWR Fernsehen BW, Sendereihe Mensch Leute, March 9, 2015 (30:00 minutes)

- Lokalzeit Südwestfalen: Der mobile Scherenschleifer. WDR Fernsehen, Sendereihe Lokalzeit, December 16, 2014 (3:40 minutes)

- Wanderschleifer – Messerschleifer „Rief". Tirol TV, Sendereihe Allerhand aus’m Tyrolerland, February 28, 2014 (3:11 minutes)

Radio[edit]

- Berufsbild: Scherenschleifer Romeo Weiß in der Deutschen Digitalen Bibliothek – Hörfunksendung des SDR. November 29, 1994. (5:35 minutes; Permalink to the archive unit R 1/005 D941071/108 im Findbuch des Landesarchivs Baden-Württemberg)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kulke, Willi (2013). "Scherenschleifer – Fremde in der Stadt". LWL-Industriemuseum; Red. (Hendrik Bönisch (Hrsg.) ed.). Hendrik Bönisch (Hrsg.): 43–52. ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1.

- ^ Großewinkelmann, Johannes; Putsch, Jochen (1989). Schmieden – Entwicklung eines Gewerbes vom Handwerk zur Fabrik (Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Rheinisches Industriemuseum, Außenstelle Solingen, Gesenkschmiede Hendrichs ed.). Köln: Rheinland-Verlag. pp. 3–5. ISBN 3-7927-1065-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g Velten, Anke (2016-06-02). "Richtig scharf gemacht". weser-kurier.de.

- ^ "Berufsgeschichte Messerschleifer Scherenschleifer". www.rief-dieschleiferei.at. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b Helmut Rief. "Der Karrenschleifer und seine Geschichte!". rief-dieschleiferei.at. Helmut Rief, Volders, retrieved November 8, 2018

- ^ a b "History of Service Wet Grinding". servicewetgrinding.com. Retrieved February 22nd, 2020.

- ^ a b c Comitato Associativo Monumento all’Arrotino: Arrotini Val Resia. arrotinivalresia.it. Comitato Associativo Monumento all’Arrotino, retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Sotelo Blanco, Olegario (1995). Los afiladores. Una industria ambulante. Barcelona: Ronsel. ISBN 84-88413-12-2.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2009). Eduardo Barreiros and the recovery of Spain. Yale University Press, New Haven. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-300-12109-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Dominguez Carballo, Jose Luis (2017-06-05): Lembranzas de Armariz: La emigración estacional o temporal >> Los afiladores. lembranzasdearmariz.blogspot.com. June 15, 2017, retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Kulke, Willi (2013). "Scherenschleifer – Fremde in der Stadt". LWL-Industriemuseum. Wanderarbeit. Klartext, Essen: 43–47. ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1.

- ^ a b Küther, Carsten (1983). Menschen auf der Straße. Vagierende Unterschichten in Bayern, Franken und Schwaben in der 2. Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts (Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft.). Vol. 56. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 62. ISBN 978-3-525-35714-9.

- ^ Kulke, Willi (2013). "Scherenschleifer – Fremde in der Stadt". LWL-Industriemuseum. Wanderarbeit. Klartext, Essen: 48. ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1.

- ^ „Asoziale“ und Jenische wurden gedemütigt. versoehnungsfonds.at. Österreichischer Versöhnungsfonds, retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Untersuchungen über die Lage des Hausiergewerbes in Deutschland. In 5 Bänden (= Verein für Socialpolitik: Schriften des Vereins für Socialpolitik". 77–81. Leipzig. 1898.

- ^ Untersuchungen über die Lage des Hausiergewerbes in Deutschland (= Verein für Socialpolitik: Schriften des Vereins für Socialpolitik. Band 78). Band 2. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1898, p. 63.

- ^ a b Kulke, Willi (2013). "Scherenschleifer – Fremde in der Stadt". LWL-Industriemuseum. Wanderarbeit. Klartext, Essen: 46–50. ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1.

- ^ Münch, Paul (2017-10-12). Bisingen: Ein Oskar Schindler aus Steinhofen? In: schwarzwaelder-bote.de. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Ruoß, Siegfried (2013). Viel Fürsten gab's und wenig Brot. Von Scherenschleifern, Bürstenbindern und anderen kleinen Leuten in Württemberg. Theiss. ISBN 978-3-8062-1770-4.

- ^ Wolpers, Christian (2015). "Mit Bildung gegen Antiziganismus". Stiftung niedersächsische Gedenkstätten. Jahresbericht: 21–23.

- ^ Floris, Julien (2012–12). «Wir sind die vierte oder fünfte Kultur der Schweiz». In: Tangram. Bulletin der EKR. Nr. 30, pp. 73–76 (deutsch, französisch, italienisch, Digital Retrieved March 1st, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Richter, Harald H. (2018-05-10). Einer der letzten in der Zunft der fahrenden Scherenschleifer. op-online.de, retrieved November 7, 2018

- ^ Stephan Reporteur. Wer schleift heutzutage noch Messer?. hausjournal.net. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ Jochimsen, Lukrezia. Zigeuner heute. Untersuchung einer Außenseitergruppe in einer deutschen Mittelstadt. Soziologische Gegenwartsfragen, N.F. 17. Enke, 1963, ISSN 0081-3265, p. 17.

- ^ Scherenschleifer gehen von Haus zu Haus: Sind es Betrüger? . pnp.de. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Unbekannter gibt sich als Messerschleifer aus und bestiehlt Ehepaar. weser-kurier.de. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Hubertus Heuel. Der ehrbare Scherenschleifer. wp.de. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Docter, Frank-O. (2017-02-18). "Scherenschleifer aus Gießen ist einer der letzten Vertreter seines Berufes". giessener-anzeiger.de.

- ^ a b Marius, Mélanie Martin (2017). Messer. Rezepte und Techniken. Vol. 1. Callwey. ISBN 978-3-7667-2282-9.

- ^ Rechtsverordnung: Chirurgiemechaniker-Ausbildungsverordnung vom 23. März 1989 (BGBl. I, S. 572). Hrsg.: Bundesgesetzblatt 1989.

- ^ a b Messer- und Scherenschleifer. ballenbergkurse.ch. Kurszentrum Ballenberg, Hofstetten bei Brienz (Schweiz), retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Zweckverband Naturpark Bergisches Land (2012). Bergische Berufe. Zweckverband Naturpark Bergisches Land, Gummersbach, pp. 6–7: Scheren- und Besteckschleifer.

- ^ F. Klopotek, J. Putsch. Entwicklungsstationen der Solinger Schneidwaren- und Besteckindstrie. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure, Bergischer Bezirksverein (Hrsg.): Technikgeschichte aus dem Bergischen Land. Menschen und Maschinen im Wandel der Zeit. Born, Wuppertal 1995, ISBN 3-87093-072-1, pp. 60–72.

- ^ Löffler, Antonia (2016-10-23). Der Mann, der den Schliff zurückbringt. Die Presse. (diepresse.com [Retrieved May 17, 2020)].

- ^ Messerschmied/in. ballenbergkurse.ch. Kurszentrum Ballenberg, Hofstetten bei Brienz (Schweiz), retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Angaben in der länderübergreifenden Informationsdatenbank Europäischer Berufsbildungsatlas.

- ^ Schriewer, Carina (2014-04-19). Sandro, der Meister der scharfen Klingen. nordbayern.de. 19. April 2014, retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Halder, Gerhard (2006). Strukturwandel in Clustern am Beispiel der Medizintechnik in Tuttlingen. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 145. ISBN 3-8258-9243-3.

- ^ Platzek, Ilka. (2019-09-13). Stets ein gefragter Mann: Der mobile Messerschleifer. In: rp-online.de. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Vgl. Hörfunkbeitrag des Rundfunksenders Österreich 1 (Ö1) (2015-10-30).

- ^ a b c d e f Kierzek, Kristine M. (2020-01-09). Local sharpening crews can help you baby your knives so they last a lifetime. In: eu.jsonline.com. Milwaukee, retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Wie die Messermacher aus Solingen überlebt haben (2019-04-13). In: capital.de. Retrieved January 31, 2020

- ^ Die zweiten 100 schwäbischen Wörter >> lfd. Nr. 182: Scheraschleifer.. heimatverein-moeglingen.de. Heimatverein Möglingen, retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ Gimmler, Klaus (2017-03-03). Gustl Krapf war der Messerschmied von Karlstadt. mainpost.de. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ Wir sind die Schleifer. lumpenlieder.de. Karl Schupp, retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Hausmann, Otto. Der Scherenschleifer. Gedicht. Wikisource.

- ^ Kratz, Robert (1980). Der Scheerenschleifer. Musikdruck. Nach einem Gedicht von Otto Hausmann.

- ^ De scheresliep / Komt vrienden in het ronde. benhartman.nl. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Des Schleifers Weis’ / Kommt Freunde in die Runde. ingeb.org. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Historische Messerschmiede. moessingen.de. Retrieved August 20, 2020. (zwei Werkstätten im Originalzustand, aus der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts und aus dem Jahr 1920).

- ^ HLFM-Faltblatt „Auf der Reis’ – Die ‚unbekannte‘ Minderheit der Jenischen im Südwesten“. wackershofen.de. Retrieved august 22, 2020. (die 2017 eröffnete Dauerausstellung informiert über Kultur und Lebensweise der Jenischen, die auf der „Reis’" unter anderem als Scherenschleifer übers Land zogen und ihre Dienstleistungen feilboten).

- ^ Bettina Hachenberg. (2020-06-24). Fahrende Leute werden in Heuberg sesshaft. STIMME.de. 24. Juli 2020, retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ Objekt des Monats August 2012: Scherenschleifkarren. (2012-08-02) industriemuseum-elmshorn.de. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ „Historisches Museum rund um Schneidwaren“ mit Erlebnis-Schleiferei. rief-dieschleiferei.at. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Collection highlights: Saw Doctor’s wagon. nma.gov.au. National Museum of Australia, retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Wanderarbeit (2013). lwl.org. LWL-Industriemuseum, retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Madonna di Campiglio >> Pinzolo >> Scherenschleiferdenkmal. In: tour.campigliodolomiti.it. Retrieved February 27, 2020 (italienisch, englisch, deutsch, siehe Informationstext im Pop-up-Fenster).

- ^ Storia della Val Rendena. La „Val da la trisa“ o la Valle dei Moleti. pinzolodolomiti.it. Retrieved February 7, 2020 (italienisch).

- ^ Schleifer-Museum – Cinte Tesino. cultura.trentino.it. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ Scherenschleifer-Museum. tarvisiano.org. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ Scherenschleifer Museum. alpenvereinaktiv.com. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Arrotini Val Resia. arrotinivalresia.it. Comitato Associativo Monumento all’Arrotino, retrieved February 7, 2020 (italienisch).

- ^ Gisela Hopfmüller, Franz Hlavac: Friaul erleben: Pflanzen – Küche – Lebensfreude. Styria Regional Carinthia, Wien 2013, ISBN 978-3-7012-0122-8, p. 198.

- ^ Monumento al Afilador. coloresymiradasanaviso.blogspot.com. Retrieved February 8, 2020 (spanisch).