Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi قصر الحير الغربي | |

|---|---|

Qasr al-Heer al-Gharbi facade | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Homs Governorate |

| Country | Syria |

| Coordinates | 34°22′28″N 37°36′21″E / 34.374444°N 37.605833°E |

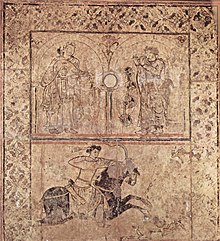

Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi (Arabic: قصر الحير الغربي) is a Syrian desert castle or qasr located 80 km south-west of Palmyra on the Damascus road. The castle is a twin palace of Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, built by the Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 727 CE. It was built in the Umayyad architectural style. As the complex was believed to be an estate owned by someone of wealth, it is no surprise that some decorations for it's opulent owners may be found within the remains of the palace. Many decorations and artwork from the complex are kept at the National Museum in Damascus.[1] Some items found within include richly decorated floor frescoes, stucco walls, and figural reliefs.

Description[edit]

Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi is one of a number of Umayyad desert castles in the Syrian/Jordanian region. The site originally consisted of a palace complex, a bath house, industrial buildings for the production of olive oil, an irrigated garden and another building which scholars suggest may have been a caravanserai. Over the entrance is an inscription which declares that it was built by Hisham in the year 727, a claim that is borne out by the architectural style.[2]

It was used as an eye of the king during the Umayyad era, to control the movement of the desert tribes and to act as a barrier against marauding tribes, as well as serving a hunting lodge. It is one of the most luxurious examples of a desert palace.[3] Later it was utilized by the Ayyubids and the Mamelukes but was abandoned permanently after the Mongol invasions.

The castle is quadrangular in outline with 70-metre (230 ft) sides. The central doorway to the castle is very attractive and has been moved to the National Museum of Damascus to be used as the entrance. Its semi-cylindrical towers on the sides of the doorway, columns, and the geometric shapes mirrored a blend of Persian, Byzantine and Arab architecture.[4]

Little of the original castle remains; however, the reservoir to collect water from Harbaka dam, a bath and a khan are still visible. The gateway is preserved as a façade in the National Museum of Damascus.

Art Found Within the Complex[edit]

Although the site of the complex features degrading architecture, several artistic works have been located, including a stucco wall and a fresco floor.[5] Similar types of art can be found in Roman architecture, but the majority of works within the complex are dated in the Umayyad period, not Roman, excluding a few constructs within the waterworks.[6] Many of the pieces found are vague or unclear whether they are based on an actual figure. One piece of artwork can possibly be identified, among the reliefs discovered in a 1936 excavation of the complex, a figural relief of man, now missing from the torso and above.[7] This finely adorned figure in Persian dress and jewelry may represent Hisham, the Caliph who commissioned the palace to be built.[8] The relief's clothing is similar in style to various artworks created in the Sassanian period, found on dinnerware and household items.[8] This continuation of style suggests that pre-Islamic artwork may have been an inspiration for the Umayyad palace. There is also evidence that the relief would have been painted rather than left in simple bare stone.[7] This attempt to create artwork inspired by previous cultures is not uncommon in Islamic works, especially in the Umayyad period, as imagery depicting Sasanian mythological creatures such as senmurv's can be found at Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi as well as more well-known complexes such as Khirbat al-Mafjar.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ Fowden, G., Qusayr 'Amra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria, University of California Press, 2004 p. 157

- ^ Petersen, A., Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 2002 , p. 238

- ^ Brend, B., Islamic Art, Harvard University Press, 1991, pp. 24–26

- ^ Milwright, Marcus (2023-12-07). A Story of Islamic Art. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-37404-6.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (2006). The Byzantine and early Islamic Near East. Variorum collected studies series. Aldershot, Hants, England ; Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5909-9.

- ^ a b "Lower half of a sculpturesque high relief - Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ a b Mourad, Suleiman A. (2020-11-25), "Umayyad Jerusalem", The Umayyad World, Routledge, pp. 393–408, ISBN 978-1-315-69141-1, retrieved 2024-04-22

External links[edit]

- "Qasr Al Hir". Syria Gate. Archived from the original on 2007-11-18.

- Genequand, Denis (2013). "Some Thoughts on Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, its Dam, its Monastery and the Ghassanids". Levant. 38 (1): 63–84. doi:10.1179/lev.2006.38.1.63. ISSN 0075-8914.