Portal:Anglo-Saxon England

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Anglo-Saxon England

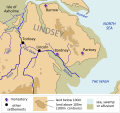

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from soon after the end of Roman Britain until the Norman Conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of England by King Æthelstan (r. 927–939). It became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway in the 11th century. The Anglo-Saxons migrated to Britain (Pretanī, Prydain) from mainland northwestern Europe after the Roman Empire withdrawal from the isle at the beginning of the 5th century. Anglo-Saxon history thus begins during the period of sub-Roman Britain following the end of Roman control, and traces the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th and 6th centuries (conventionally identified as seven main kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex); their Christianisation during the 7th century; the threat of Viking invasions and Danish settlers; the gradual unification of England under the Wessex hegemony during the 9th and 10th centuries; and ending with the Norman Conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. The Normans persecuted the Anglo-Saxons and overthrew their ruling class to substitute their own leaders to oversee and rule England. However, Anglo-Saxon identity survived beyond the Norman Conquest, came to be known as Englishry under Norman rule, and through social and cultural integration with Romano-British Celts, Danes and Normans became the modern English people. (Full article...) Selected articleLindsey or Linnuis (Old English Lindesege) was a lesser Anglo-Saxon kingdom, absorbed into Northumbria in the 7th century. It lay between the Humber estuary and the Wash, forming its inland boundaries from the courses of the Witham and Trent rivers, and the Foss Dyke between them. A marshy region south of the Humber known as the Isle of Axholme was also included. Place-name evidence indicates that the Anglian settlement known as Lindisfaras spread from the Humber coast. Lindsey means the 'island of Lincoln': it was surrounded by water and very wet land, and Lincoln was in the south-west part of the kingdom. Although it has its own list of kings, at an early date it came under external influence. It was from time to time effectively part of Deira, of the Northumbrian kingdom, and particularly later, of Mercia. Lindsey lost its independence long before the arrival of the Danish settlers. The kingdom's heyday seems to have come before the historical period. By the time of the first historical records of Lindsey, it had become a subjugated polity, under the alternating control of Northumbria and Mercia. All trace of its individuality had vanished before the Viking assault in the late ninth century. Its territories evolved into the historical English county of Lincolnshire, the northern part of which is called Lindsey. (more...) Did you know?

SubcategoriesSelected image The Devil's Dyke (also called Reach Dyke or Devil's Ditch, once known as St Edmund's Ditch) is an earthwork near the village of Reach that is generally assumed to be an Anglo-Saxon earthwork. It is one of the largest and best surviving examples of its kind in England. Selected biographyAugustine of Canterbury (circa first third of the 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a Benedictine monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.[1] Augustine was the prior of a monastery in Rome when Pope Gregory the Great chose him in 595 to lead a mission, usually known as the Gregorian mission, to Britain to Christianize King Æthelberht and his Kingdom of Kent from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Before reaching Kent the missionaries had considered turning back but Gregory urged them on and, in 597, Augustine landed on the Isle of Thanet and proceeded to Æthelberht's main town of Canterbury. King Æthelberht converted to Christianity and allowed the missionaries to preach freely, giving them land to found a monastery outside the city walls. Augustine was consecrated as a bishop and converted many of the king's subjects, including thousands during a mass baptism on Christmas Day in 597. Pope Gregory sent more missionaries in 601, along with encouraging letters and gifts for the churches, although attempts to persuade the native Celtic bishops to submit to Augustine's authority failed. Augustine also arranged the consecration of his successor, Laurence of Canterbury. The archbishop probably died in 604 and was soon revered as a saint. (more...) Things you can do

Featured articles and lists

Related portalsWikiProjects

Associated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

| |||||||||||||||||

- ^ Delaney Dictionary of Saints pp. 67–68