Luigi Pio Tessitori

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Luigi Pio Tessitori | |

|---|---|

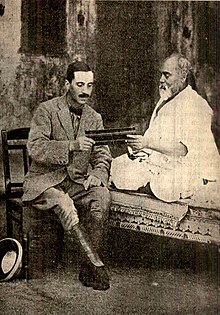

L P Tessitori and Jainacharya Vijaya Dharma Suri | |

| Born | 13 December 1887 Udine, Italy |

| Died | 13 November 1919 (aged 31) |

| Resting place | Bikaner, Rajasthan, India 28°01′09″N 73°19′35″E / 28.019097°N 73.326358°E |

| Parents |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | History, archaeology |

| Institutions | Archaeological Survey of India |

Luigi Pio Tessitori (13 December 1887, in Udine – 22 November 1919, in Bikaner) was an Italian Indologist and linguist.

Biography[edit]

Tessitori was born in the north-eastern Italian town of Udine on 13 December 1887, to Guido Tessitori, a worker at the Foundling Hospital, and Luigia Rosa Venier Romano. He studied at the Liceo Classico Jacopo Stellini before going on to university.[1] He studied at the University of Florence, obtaining his degree in the humanities in 1910. He is said to have been a quiet student, and when he took up the study of Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit, his classmates gave him a nickname Indian Louis.[1]

Having developed an abiding interest in north Indian vernacular languages, Tessitori tried hard to obtain an appointment in Rajasthan. He applied in 1913 to the India Office; realising that there was no guarantee of a job offer, he also approached Indian princes who might employ him for linguistic work. Around this time, he established contact with a Jain teacher, Vijaya Dharma Suri (1868-1923) with whom he was to have a close personal and professional relationship.[1] Suri was known for his deep knowledge of Jain literature, and was instrumental in the retrieval and preservation of many of its works. Tessitori appealed to him for criticism of his exegeses on Jain literature and practises. Suri offered him a position at a Jain school in Rajasthan, but while negotiating the delicate position of a Christian living in a Jain community, Tessitori received approval for his application from the India Office, and made preparations to head to India in 1914.

In India, Tessitori involved himself with both its Linguistic Survey and the Archaeological Survey, and made discoveries of fundamental importance to Indology.

In 1919, he received news that his mother was seriously ill, and he left for Italy on 17 April. By the time he arrived, she was dead. He stayed in Italy for several months before returning to India in November. Unfortunately, he apparently contracted Spanish influenza on board his ship, and fell seriously ill. He died on 22 November 1919 in Bikaner.[1]

Career[edit]

Thesis and Early Work[edit]

Between 1846 and 1870, twelve volumes of the Bengali or Gauda version of Valmiki's Ramayana were published in Italy by Gaspare Gorresio,[2] which became an important reference for Italian Indologists. Tessitori's thesis was based on this work, and involved an analysis of the connections between it and Tulsidas's version, written in Avadhi nearly a thousand years later. He showed that Tulsidas had borrowed the main story from Valmiki, expanding or reducing the particulars, but retelling them in a poetic form that was independent of the original, and hence could be considered a new work. It was painstaking research involving a verse-by-verse comparison of the two versions, and showing that Tulsidas had followed different versions of the Ramayana that were extant in India at the time.[1] His thesis[3][4] was published under the supervision of Paolo Emilio Pavolini in 1911.[5]

Linguistic Survey of India[edit]

The Asiatic Society of Bengal invited Tessitori to join its Linguistic Survey of India. He was tasked by Sir George Grierson to lead the Bardic and Historical Survey of Rajputana. He arrived in 1914 and stayed in Rajputana for five years.[6] He translated and commented upon the medieval chronicles and poems of Rajasthan, several of which he had earlier studied at Florence's national library.[1] He studied the grammar of old Rajasthani along the same comparative lines as he had with his thesis, and laid the foundations of the history of the development of modern Indo-Aryan vernaculars.[1]

Tessitori explored the poetic compositions in the Dingal and Pingala dialects, and genealogical narratives. He managed to catalogue the private bardic libraries and several princely state libraries, despite some bureaucratic opposition.[1]

In 1915, invited by the Maharaja of Bikaner, Tessitori arrived in that state and began lexicographic and grammatical studies in the regional literature. He was able to show that the dialect hitherto called Old Gujarati should more properly be called Old Western Rajasthani.[5] He was also much taken with the beauty of Rajasthani dialects, and critically edited several exemplars of their literatures, such as the Veli Krishna Rukmani Ri of Rathor Prithviraja, and Chanda Rao Jetsingh Ro of Vithu Suja.[5]

Archaeology[edit]

Along with his linguistic work, Tessitori ranged across Jodhpur and Bikaner in search of memorial pillars, sculptures, coins, and archaeological sites on behalf of Sir John Marshall of the Archaeological Survey of India.[6]

Tessitori retrieved Gupta terracottas from mounds in Rangamahal and other locations, as well as two colossal marble images of the goddess Saraswati near Ganganagar. He found Kushan-period terracottas at Dulamani, also in Ganganagar. He also decoded and published the texts of epigraphs on stone (Goverdhan) pillars and tablets in the Jodhpur-Bikaner region.[5]

He noted the proto-historic ruins in the Bikaner-Ganganagar region, correctly pointing out that these predated Mauryan culture. This finding enabled the later discovery and excavation of the Indus Valley civilization site of Kalibangan.[5] He communicated the discovery of three objects from Kalibangan to Sir George Grierson during his brief stay in Italy in 1919.

Two of them - the first one is a seal - bear an inscription in characters which I am unable to identify. I suspect it is an extremely interesting find: the mound itself on which the objects were discovered, is very interesting. I believe it is prehistorical or, at least, non-Aryan. Perhaps the inscriptions refer to a foreign race?

Grierson suggested he show them to John Marshall upon his return to India. This he was unable to do as he died when he got back to Bikaner. The knowledge of the seals was buried with him,[1] and was recovered only when Hazarimal Banthia, a Kanpur businessman, brought back copies of his correspondence from Italy.[7]

Bibliography[edit]

- "On the Origin of the Dative and Genitive Postpositions in Gujarati and Marwari". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 45 (3). July 1913. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00045123. S2CID 163230979.

- "Notes on the Grammar of the Old Western Râjasthânî with Special Reference to Apabhraṃśa and to Gujarâtî and Mârvâṛî". Indian Antiquary. XLIII–XLIV: 1–106. 1914–16.

- "On the Origin of the Perfect Participles in l in the Neo-Indian Vernaculars". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 68. 1914.

- "Old Gujarati and Old Western Rajasthani". Proceedings of the Fifth Gujarati Sahitya Parishad. May 1915.

- "Vijaya Dharma Suri - A Jain Acharya of the Present Day". Bikaner: Shri Vriddhichandraji Jain Sabha. 16 November 1917.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Vacanikā Rāthòṛa Ratana Siṅghajī rī Mahesadāsòta rī Khiriyā Jaga rī kahī". Bibliotheca Indica: 1–139. 1917.

- "Descriptive Catalogue of Bardic and Historical Manuscripts from Jodhpur". Bibliotheca Indica: 1–69. 1917. (prose chronicles)

- "Descriptive Catalogue of Bardic and Historical Manuscripts from Bikaner States". Bibliotheca Indica: 1–94. 1918. (prose chronicles)

- "Veli Krisana Rukamanī rī Rāthòra rāja Prithī Rāja rī kahī". Bibliotheca Indica: 1–143. 1919.

- Bardic and historical survey of Rajputana : a descriptive catalogue of bardic and historical manuscripts. 1917.

- "Chanda rāu Jètā Sī rò. Vīthu Sūjè rò kiyò". Bibliotheca Indica: 1–113. 1920.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nayanjot Lahiri (2012). Finding Forgotten Cities: How the Indus Civilization was discovered. Hachette India. ISBN 978-93-5009-419-8.

- ^ Gorresio, Gaspare (1869). Il Ramayana di Vālmīki (in Italian). Milan: Ditta Boniardi-Pogliani di Ermenegildo Besozzi.

- ^ Luigi Pio Tessitori (1911). "Il "Rāmacaritamānasa" e il "Rāmāyaṇa"". Giornale della Società Asiatica Italiana (in Italian). XXIV: 99–164.

- ^ Luigi Pio Tessitori (1912–13). "Ramacarita Manasa, a parallel study of the great Hindi poem of Tulsidasa and of the Ramayana of Valmiki". Indian Antiquary. XLI–XLII: 1–31.

- ^ a b c d e Vijai Shankar Srivastava, ed. (1981). Cultural Contours of India: Dr. Satya Prakash Felicitation Volume. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-0-391-02358-1.

- ^ a b "Luigi Pio Tessitori". Società Indologica «Luigi Pio Tessitori». Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Nayanjot Lahiri (18 June 2012). "Buried over time". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012.

External links[edit]

- Tessitori.org

- Centre for Rajasthani Studies

- Ethnologue Report for Rajasthani

- A progress report on the work done during the year 1917 in connection with the Bardic and Historical Survey of Rajputana