Hanam Jungwon

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Hanam Jungwon 漢巖重遠 | |

|---|---|

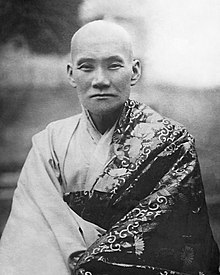

Hanam Jungwon between 1926-1935 | |

| Title | Dae Jong Sa (Great Head of the Order) |

| Personal | |

| Born | Bang March 27, 1876 |

| Died | March 21, 1951 (age 74) Sangwon Temple, Odae Mountains, South Korea |

| Religion | Buddhist |

| Nationality | Korean |

| School | Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism |

| Notable work(s) | Spiritual Head of the Jogye Order(宗正), head of the meditation hall at Sangwon Temple |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Gyeongheo Seong-u 鏡虛 惺牛 (1846-1912) |

Hanam Jungwon (1876–1951, 漢巖重遠) was a Korean Buddhist monk and Seon master. He was also the spiritual head(宗正) of what was to become the modern Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. He was the Dharma disciple of Gyeongheo Seongu (鏡虛 惺牛,1846-1912), and the Dharma brother of Woelmyeon Mangong (月面滿空, 1871–1946).

Early life[edit]

Hanam Sunim was born to an upper-class family in 1876 and received a traditional education in the Confucian classics, but at the age of 20, he left home and became a monk. He entered Jangan Temple(長安寺) in the Diamond Mountains of present-day North Korea, and his guiding sunim was Haenglŭm Kŭmwŏl. Some time later he left there to continue his studies at Singye Temple(神溪寺). After several years, he came across a passage by the Koryo Dynasty Seon Master, Bojo Jinul, in Secrets on Cultivating the Mind:

If they aspire to the path of the Buddha while obstinately holding to their feelings that the Buddha is outside the mind or the Dharma outside the nature, then, even though they pass through kalpas as numerous as dust motes, burning their bodies, charring their arms, crushing their bones and exposing their marrow, or else copying sutras with their own blood, never laying down to sleep, eating only one offering a day at the hour of the Hare (5-7 a.m.), or even studying through the entire Tripitaka and cultivating all sorts of ascetic practices, all of this is like trying to make rice by boiling sand―it will only add to their tribulation (Buswell 1983: 140-141).

This precipitated his first enlightenment experience, in 1899.

The essence of that passage, "don't search for the Buddha outside of yourself," stayed with Hanam Sunim throughout his life.

After Hanam Sunim's first enlightenment experience, he made his way south to Sudo Hermitage,9 he met Kyŏnghŏ Sunim.10 Meeting Hanam Sunim, Kyŏnghŏ Sunim quoted the following phrase from the Diamond Sutra:

If one sees all forms as non-form, then can one directly see the Tathagata" (T.8.749a24-25).[1]

Upon hearing this, Hanam Sunim experienced a second enlightenment, and "felt that the whole universe could be seen in one glance and whatever was to be heard or seen was nothing other than that which was within himself." He composed the following poem:

Under my feet, the blue sky, overhead, the earth.

Inherently there is no inside or outside or middle.

The lame person walks and the blind person sees.

The north mountain answers the south mountain without words.(Pang 1996: 453)

From 1899 to 1903, Hanam Sunim spent the retreat seasons either studying under Kyŏnghŏ Sunim or attending retreat seasons at other meditation halls in the region. They spent the summer retreat season of 1903 together at Haein Temple, and later that fall, Kyŏnghŏ Sunim headed north by himself. He died in 1912.

1904-1912[edit]

In 1904, at the age of 29, Hanam Sunim became the head of the meditation hall at Tongdo Temple(通度寺). However, in 1910, while studying a scripture, he came across a passage that he himself didn't fully understand. The next day he ordered the meditation hall closed and made his way to Udu Hermitage near Maeng-san district in Pyŏngan-do (in the northwestern area of present-day North Korea) in order to continue his practice. He stayed in that area until at least 1912. One day, while starting a fire, Hanam Sunim had his third enlightenment experience, and composed the following poems:

Making a fire in the kitchen, suddenly my eyes became bright.

It's clear that the path leading here was due to karmic affinity,

if someone were to ask me why Bodhidharma came from the west,

I'd say that the sound of a spring under a rock is never wet.

The dogs in the village bark, suspicious of me

magpies cry out, as if mocking me.

Eternally shining, the bright moon that is mind,

swept the wind out of the world in an instant (Pang 1996: 456-457).

1912-1926[edit]

Very little is known about this time in Hanam Sunim's life. As the Maeng-san district is only 70-80 kilometers south of the Myohyang Mountains, it's probable that Hanam Sunim spent time at different temples there. The Myohyang Mountains are large mountainous area in the far north of Korea, and at the time were a major Buddhist center, with several large, important temples and many smaller hermitages. Given Hanam Sunim's reputation as a disciple of Gyeongheo, and his time as head of the meditation hall at Tongdo Temple, it would not be unusual for the sunims in this area to ask him to fulfill a similar role. A well-known saying of "Mangong in the south, Hanam in the north" may date from this time. (At the time, Mangong Sunim was at Sudeok Temple, which is about 1.5 hours south of Seoul by car.)

Hanam Sunim was in the Diamond Mountains, at Jangan Temple by 1922,[2] and later just outside Seoul at Bongeun Temple in 1926. He left then and, perhaps intending to return to the Diamond Mountains, wound up staying in the Odae Mountains, at Sangwon Temple. (This would have been on his path to the Diamond Mountains.) As he was a very well known teacher, it seems likely that the monks at the nearby large temple, Woljeong Temple, had asked him to stay and teach.

1926-1951[edit]

Hanam Sunim was famous for the diligence of his spiritual practice, and it is often said that during the last 25 years of his life he never once left his temple, Sangwon Temple, in the Odae Mountains. Many people, hearing of this, assume that it was because of his spiritual practice that he wouldn't leave. However, a close examination of Hanam Sunim's letters reveals that he actually did leave the Odae Mountains at least twice between 1926 and 1933. What kept him there in later years appears to have been his responsibility for the sunims practicing in the Odae mountains, combined with his ill-health. Hanam Sunim repeatedly refused to go to Seoul, where he would have been at the bidding of the Japanese government, and it seems that people confused this as a desire to stay in the Odae Mountains. In a conversation with the Japanese Superintendent of Police, Hanam Sunim plainly states that he'd gone to Seoul to visit a dentist, and south to see Bulguk Temple.[3] This was confirmed by his long-time correspondent, Kyeongbong Sunim, who living nearby at Tongdo Temple, recorded in his diary that Hanma Sunim visited him for several days before returning to the Odae Mountains.[4](c.f. Chong Go 2007: 75)

During this time, he was frequently elected to high leadership positions within Korean Buddhism, usually without his consent. In 1929 he was elected one of the seven patriarchs of Korean Buddhism during the Grand Assembly of Korean Buddhist Monks(Chosŏn Pulgyo sŭngnyŏ taehoe). He was elected as vice chairman of the meditation society, Sŏn hakwŏn in 1934, and in 1936 he was elected as the Supreme Patriarch of the Jogye Order, and again in 1941, when it was reorganized. He resigned in 1945, but was again elected in 1948 and asked to serve as Supreme Patriarch. (Chong Go 2008: 124)

Death[edit]

Hanam Sunim is perhaps most popularly known for the events leading up to his death.

During the Korean War, a Chinese army offensive broke through the UN lines in January 1951 and was rapidly advancing south. The South Korean army was ordered to burn all of the buildings in the Odae Mountains in order to deny shelter to the advancing Chinese troops. WolJeong Temple could be seen burning when a squad of South Korean soldiers arrived at Sangwon Temple. Explaining their mission, they ordered everyone to pack what they could and leave immediately. Instead, Hanam Sunim returned to the Dharma Hall, put on his formal robe, and, sitting down, told the lieutenant to go ahead and burn the buildings. Hanam Sunim then told the lieutenant that his since his job was to stay with the temple, and the lieutenant's was to burn it, there would be no conflict(or bad karma) because they were both just doing their job. The lieutenant couldn't get Hanam Sunim to leave, and so at great risk to himself (for disobeying orders in wartime) he instead piled all of the wooden doors and window shutters in the courtyard and burned those instead. In this way, Sangwon Temple was one of the few temples in this area to survive the war.[5][6]

Hanam Sunim died two months later, on March 21, 1951, following a brief illness.

Teachings[edit]

Hanam Sunim was known for the diligence with which he upheld the traditional precepts for a Buddhist monk, along with the sincerity of his practice. As the head of the meditation hall at Sangwon Temple(上院寺), he had monks study sutras and learn ceremonies during the meditation retreat. This was unprecedented, but he explained that such long periods of meditation were actually the most appropriate times to study those things. He also said that monks should be adept at five things: Meditation, chanting, understanding the sutras, performing any needed ceremonies, and maintaining and protecting the temple. (See also Ulmann, 2010, for more about this.[7])

He was also quite flexible in his approach to hwadus(koans) and the meditation method known as silent illumination, emphasizing that neither method was inherently better or worse than the other. Instead it came down to which was best suited to the student.

Hwadu/koan, reflective illumination, and chanting[edit]

Hanam Sunim didn't particularly discriminate between the different methods of Buddhist spiritual practice. For example, in an article titled "21 Seon Questions and Answers,"[8] he gave several examples of how great Seon masters of the past had used both Hwadus and Reflective Illumination to teach different disciples, and in "Five Things that Sunims Should Practice," he explained how reciting the name of Buddha could lead to the state that transcended the discriminating consciousness, and thus lead to awakening.[9]

Good results can be obtained through either holding a hwadu or through reflective illumination(返照). So how can one be called shallow and the other deep? It's not possible to talk about all of the cases whereby previous Seon masters have showed this through their lives. None of them discriminated between holding a hwadu and reflective illumination. However practitioners today accuse each other and think that the other person is wrong. Where on earth did they learn this?![10]

In general, Hanam Sunim's view of spiritual practice seems to be one of "Skillful Means," rather than absolute methods. For example, in "21 Seon Questions and Answers," when he was asked about which hwadus were best to practice with, before going on to give a detailed explanation of traditional hwadu practice, Hanam Sunim first replied,

People of high ability just take whatever confronts them and use it straightaway." [11]

Cause and effect/karma[edit]

Many of the monks who knew Hanam Sunim commented on his strong faith in the teachings of cause and effect. This belief is seen numerous places in his writings.

Zingmark[12] relates the following stories that convey a sense of Hanam Sunim's faith in cause and effect:

On February 22, 1947, two junior monks were studying in a small building within the Sangwŏn Temple compound. They left a candle burning when they went outside, and this was the cause of the fire that burned down the entire temple. However, when Hanam Sunim describes the fire to Kyŏngbong Sunim he didn't blame anyone specifically. Instead, he attributes the fire to the workings of cause and effect in which he and everyone else at the temple played a role:

Due to my own lack of virtue and the unhappy fortune of this temple, on February 22, towards sunset, a violent wind arose and in the new building a fire started. [13]

Between 1945 and 1950, there were increasing conflicts within the Jogye Order between the monks who had married during the Japanese occupation and those monks who had kept the traditional precepts. The tone of these conflicts was increasingly strident and there were even incidences of violence. These events led Hanam Sunim to issue a statement in the fall of 1949 saying that all of these problems should be solved harmoniously.[14] Hanam Sunim alludes to these problems in his 23rd letter to Kyŏngbong Sunim:

As (the spiritual head of the Jogye Order) I can't help but be concerned about whether our order flourishes or collapses, and whether the Buddha-dharma prospers or declines. However, we receive things according to how we have made them, so there's no point in worrying or lamenting about them. [15]

In addition to his own belief in cause and effect, Hanam Sunim(in his second letter) also warns Kyŏngbong Sunim to be cautious of others who ignore cause and effect.

Don't follow the example of those shallow people who misunderstand the meaning, who are too stubborn, who ignore the principle of cause and effect, and who don't understand that what they receive is the result of their own actions. [16]

References[edit]

- ^ Diamond Sūtra (金剛般若波羅密經: Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra), Chinese trans. by Kumārajīva (鳩摩羅什). T.8, no.235.

- ^ "Sŏnjung banghamlokso" (Address to the Assembly of Sunims at KŏnbongTemple), Pang, 1996, p. 335.

- ^ Yamashita, Jinichi 山下 眞一 1934. "Ikeda-kiyoshi keibu kyokuchō wo Hōkangan zenji fu hō (池田淸警務局長を方漢巖禪師ふ訪: Police Superintendent Ikeda-kiyoshi visits Sŏn Master Pang Hanam)." Chōsen bukkyō (朝鮮佛敎) 101: 4-5.

- ^ Sŏk,Myŏngjŏng,釋 明正 ed. 1992 Samsogul ilji (三笑窟 日誌: Samsogul Diary). South Korea: Kŭngnak sŏnwŏn, 102-104.

- ^ Kim, Gwang Shik (August 1, 2010). "'상원사에 불을 지르란 한암스님' 한마음선원장 대행스님 입적" [Hanam Sunim gives the order to set fire to Sangwon Temple]. Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ "Hanam Sunim". Odaesan Woljeongsa (in Korean). Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ Uhlmann, Patrick (2010). Son Master Pang Hanam: A Preliminary Consideration of His Thoughts According to the Five Regulations for the Sangha (in Makers of Modern Korean Buddhism). SUNY. pp. 171–198. ISBN 9781438429229.

- ^ Pang, Hanam(方 漢巖) (1996). Hanam ilballok(漢巖 一鉢錄: The One Bowl of Hanam). Seoul: Minjoksa. pp. 48–53. ISBN 9788970096339.

- ^ Pang 1996, p. 28.

- ^ Pang 1996, p. 53.

- ^ Pang 1996, p. 41.

- ^ Zingmark, B.K. (2002). A Study of the letters of Korean Seon Master Hanam (Master's Thesis ed.). Seoul, Korea: Dongguk University. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Pang 1996, p. 280.

- ^ Pang, Hanam (October 5, 1949). "Daehoesojibul tŭkmyŏng (Special Order to the Assembly)". Bulgyo shinbo, p. 1.

- ^ Pang 1996, p. 286.

- ^ Pang 1996, p. 232.

Korean

- Pang, Hanam(方 漢巖). (1996) Hanam ilballok (漢巖 一鉢錄: The One Bowl of Hanam), Rev. ed. Seoul: Minjoksa, 1996.

- Kim, Kwang-sik(金光植). (2006) Keuliun seuseung Hanam Seunim (그리운 스승 한암: Missing our Teacher, Hanam Sunim). Seoul:

Minjoksa.

English

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.(1983) The Korean Approach to Zen: The Collected Works of Chinul. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press

- Chong Go. (2007) "The Life and Letters of Sŏn Master Hanam." International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture September 2007, Vol.9, pp. 61–86.

- Chong Go. (2008) "The Letters of Hanam Sunim:Practice after Enlightenment and Obscurity." International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture February 2008, Vol.10, pp. 123–145.

- Uhlmann, Patrick. (2010) "Son Master Pang Hanam: A Preliminary Consideration of His Thoughts According to the Five Regulations for the Sangha." In Makers of Modern Korean Buddhism, Ed. by Jin Y. Park. SUNY Press, 171–198.

- Zingmark, B.K.靑高 2002 A Study of the letters of Korean Seon Master Hanam. Unpublished master's thesis, Seoul: Dongguk University.

External links[edit]

"Hanam Sunim". Odaesan Woljeongsa (in Korean).