Greeks in South Sudan

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 90, + unknown number of descendants | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Juba, Wau | |

| Languages | |

| English, Greek, others Languages of South Sudan | |

| Religion | |

| Greek Orthodox Church, Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Greeks, White Africans of European ancestry |

The Greeks in South Sudan represent the Omogenia in what became the Republic of South Sudan in 2011. The population is tiny in number – estimated at around 90 – but historically played an important role and has some prominent members, especially First Lady Mary Ayen Mayardit.[1]

History[edit]

Pre-modern times[edit]

It is unclear when the first inter-human and cultural exchange between Hellenic and Southern Sudanese civilisations took place. However, since Greek contacts with the Nubian kingdoms of Northern Sudan have been established going back more than two and a half millennia,[2] it may well be argued that through Southern Sudanese exchanges with Nubia there were at least indirect relations since ancient times. Scholars in Ancient Greece were evidently inspired with curiosity about the exotic lands further South and particularly about the sources of the River Nile. Most prominently, the pioneering historian Herodotus (c. 484-c. 425 BCE) made bizarre references to a savage land of the "burnt faces" (Aithiopia).[3]

As Hellenic culture continued to inspire and influence the Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria and Alwa in medieval times,[4] it may likewise be argued that indirect contacts between Southern Sudanese societies and the Greek world may well have to continued through Nubia. Before migrating to their modern location the South Sudanese Dinka people lived in close proximity to Alwa, a relation confirmed by the considerable impact the Nubian language had on the Dinka vacabulary.[5]

Turkiya (1821–1885)[edit]

When the Turkish-Egyptian forces of the Ottoman Khedive Mohamed Ali conquered the Funj kingdom in 1821, the invading army reportedly included Greek mercenaries of Arvanite origin – who helped pave the. way for the subsequent conquest of Southern Sudanese lands.[1]

As more Greeks followed the invaders from Egypt into Northern Sudan, some of them guided expeditions further southward. Greek merchants, who ventured South, were mainly interest in dealing with ivory.[6] Their number and commercial activity greatly increased after the monopoly of trade was abolished in 1849 and the White Nile was opened for navigation.[7]

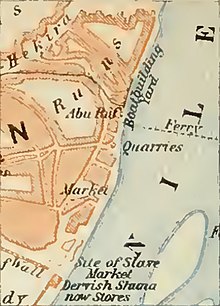

Some also became involved in the trade of slaves, which devastated large parts of Southern Sudan until the 1870s. The Greek historian Antonios Chaldeos, who has written his PhD thesis about the history of the Greek communities in Sudan, strongly suggests from the local histories of Omdurman residents that one of those slave-traders was George Averoff,[6] who is still widely considered a "philanthropist" and "one of the great national benefactors of Greece". The Omdurman quarter of Abu Ruf is still today named after Averoff.[6]

Other Greeks did not come to Southern Sudan for commercial reasons though. For instance, Panayotis Potagos, a Greek traveller and physician, explored Bahr El Ghazal in 1876–77.[3]

Mahdiya (1885–1898)[edit]

After the 1885 victory of the indigenous Northern Sudanese Mahdist movement over the Egyptian-Turkish rule, the Islamists also took control of most of what is now South Sudan, but held on to it rather loosely – which prompted imperialist Belgian and French missions into Southern Sudan. It may have been in this context that in 1895 a Greek merchant by the name of Grigoris Apostolidis became active in Sambi on the While Nile. He originated from Imvros and after a few years moved on to open a shop Yirol. He married a local woman and had two sons with her.[1]

Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899–1955)[edit]

Soon after the defeat of the Mahdist regime and the subsequent Fashoda incident in 1898, the British-dominated colonial regime started establishing control in Southern Sudan. At the same time, Greek merchants once again followed the invaders. The most important player in those early years was business-magnate Angelo Capato, who hailed from the Ionian island of Cephalonia and had been supplying the British Army and Navy in the Red Sea port town of Suakin since 1883.[8] He held British nationality and was particularly close with Governor-General Reginald Wingate:[1]

"around 1900, the government granted him, against a promise to supply the expeditionary force with necessary provisions, the monopoly (for two or three years?) of the ivory trade in Equatoria"[8]

According to Chaldeos, Capato also received such an exceptional license doing ivory trade in Bor. Another focus of his commercial activities was the region of Bahr El Ghazal. He set up a network of trading-posts across Southern Sudan to collect ivory and cater to colonial officials.[1] For these enterprises he mainly recruited Greek agents, preferably from his home island of Cephalonia and especially from his family there.[8] His business empire soon expanded into the Belgian-controlled Congo Free State,[9] whereby he contributed to the creation of a Greek community in Congo that still exists today.[10] Capato's agents also provided information about the Belgian-controlled Lado Enclave to the British intelligence officers in Khartoum.[11]

When Capato after a string of misfortunes – amongst them a fire that destroyed his storehouse in Gondokoro – had to declare bankruptcy in 1912,[8] many of his agents continued the business on their own. The colonial government supported this immigration as it preferred giving licences to Greek, Jewish, and Syrian merchants, rather than to Northern Sudanese "Jellaba" traders.[12]

In the region of Upper Nile, a few Greeks settled in Malakal, Bor – which was a center of ivory trade – and Taufikia. In Equatoria, some Greeks – mostly ivory traders, but also a few contractors, engineers and employees – settled in Maridi, Yambio, Tambura, Nzara, Li Yubu, Ezo, Yei, and Mongalla. The greatest number of Greeks, however, settled in Bahr El Ghazal, mainly in its commercial centre Wau,[1] where in 1910 fifteen Greek merchants were reported to make large profits.[13] The Comboni missionary priest Stefano Santandrea, who served in Wau from 1928 to 1948 and then until 1955 in Deim Zubeir, stressed though that "their competition prevented their [Northern] rivals from exploiting the natives."[14]

Some Greeks went to set up shops in more remote places of the region, like Aweil, Deim Zubeir, Kossinga, Meshra er Req, Raga, Rumbek, Tonj[1] and Luonyaker.[15] Other Greeks soon went on to settle in the Belgian Congo, French Central Africa and other African lands.[16]

When Juba – next to Gondokoro – was developed in the 1920s as the new capital of Mongalla province, "Greeks and Cypriots played a significant role, which is especially evident in brick architecture that are found around Juba's urban center."[17] The prominent Greek-South Sudanese entrepreneur George Ghines claims that

«The first settlers came to Pageri (Eastern Equatoria), just a few miles from the border town of Nimule, a busting trading area. From there, they decided to be closer to the British Encampment in Mongalla and chose a strategic place on the opposite side of the White Nile, which later became Juba. Being a pure ancestral land of the Bari Community, the first Greeks established friendly relationship with the Baris and gained their trust. The Baris and later the British appreciated the entrepreneurship of the Greeks and encouraged them to invest more, mostly into trading and services. [..] Hotels, bakeries, café, grocery shops, small industries, cinema and other commercial places, were mostly owned and run by the Greeks who considered Sudan their own new country and Juba their home.»[citation needed]

Based on archival research, the anthropologist Brendan Tuttle describes the scenery in Juba as follows:

«By the mid-1930s, travelers disembarking at the quay, where the White Nile steamer tied up, would have found themselves on a small wharf not far from the heart of a little colonial town of about twelve-hundred people. Directly in front of them lay a short stretch of road running parallel to the river. The well-stocked store of Mr. Crassus, a Greek merchant, stood at the crossroads, flanked by two shops with Indian proprietors and a row of small workshops and warehouses, a bakery, and several small cottages.»[18]

In 1935, when there were about forty Greeks living in Juba, they founded the Hellenic Community Juba with the intention to set up a Greek-Orthodox church and a school. Gerasimos Contomichalos, a nephew of Capato's and the most eminent business magnate in Sudan, made a substantial donation to the association. Fund-raising for the church building took until 1951 though, when Stelios Roussos made a large donation. In honour of the benefactor the church was named after St. Stylianos and opened in 1954.[1] The Hai Jalaba area of Juba became known as the Greek quarter of town. There were two social clubs by that time.[19]

In Wau, where about fifty Greeks were living in the late 1930s, the Greek Community of Bahr El Ghazal was founded in 1939. A plot of land was granted to it by the authorities, where the community started to construct building that were rented out in order to create a sustainable revenue source for the association. Accordingly, the construction of other buildings was postponed and the Church of Prophet Elias – named after the benefactor Elias Papoutsidis – only opened in 1955. At that time, the community had about 65 members.[1]

Republic of Sudan (1956–2011)[edit]

While the Greeks in Southern Sudan seem to have continued to prosper in the first few years after Sudan's independence, a sign of increasing instability occurred in 1960, when many of them gave refuge to Greeks who fled the Congo Crisis.[1] Just a few years later they themselves came under pressure, as the Anyanya insurgency escalated across the Southern Sudanese region from 1963 on: after a rebel assault on Wau in early 1964, the military regime of Ibrahim Abboud reportedly "announced that foreign traders would only be allowed to reside in provincial or district capitals in the South, where they could be kept under surveillance, and not in villages. This restriction was aimed at Syrian and Greek traders, who were suspected of helping the rebels."[20]

Shortly afterwards, four Greek merchants were taken to court for charges of having collected donations for the insurgents, but were acquitted.[21] At the end of 1964 two Greek traders in Bahr Al-Ghazal and Equatoria respectively were arrested on charges of acting as a link between rebels and the outside world.[22] In fact, an internal Anyanya paper claimed that "Greek merchants of Tembura helped by providing supplies" to a rebel camp in the Central African Republic.[23]

In 1967, two grandsons of Dimitri Yaloris, a Greek formerly based in Gogrial, and his Dinka wife, were killed in Bahr El Ghazal after being accused of supporting the Anyanya rebels.[24] According to Chaledos, they were targeted by the army in a special operation, since they had indeed supplied arms to the insurgents through their enterprise.[1]

Moreover, the Greeks of Southern Sudan, many of whom had married locals, came under pressure from both warring sides: while the accusations from Khartoum continued,[25] Southern opposition forces accused Greek monopolists of keeping the prices of animals "as low as possible to their own advantage" for export to the Middle East.[26] Thus, the Greek community in the South further diminished during the 1960s,[1] after its numbers had already decreased in the years before 1956.[14] In Bahr El Ghazal, many Greeks left from smaller towns and moved to the provincial capital Wau with its established community premises.[27]

On the other hand, the Greeks in Southern Sudan seemed to be more resilient than the Greeks in what was then Northern Sudan, where the big exodus started in 1969 with the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry and its nationalisation policies. Reportedly up to 90% of the Greeks in the South had married locals, whereas such relationships were rare in the North.[28] Thus it may be argued that the descendants of bi-cultural couples were more rooted in Southern Sudan. A 2014 Durham University thesis quotes a Gogrial resident:

"Among the traders I should mention ‘Gorgor’ he was a Greek trader who was famous. He married from Wau...his son was very white, but could speak Dinka and he used to sing Dinka songs."[15]

However, the Norwegian-Greek historian Alexandros Tsakos concludes that the relationship between the "class" of "pure" Greeks and those of "mixed blood", "who sarcastically call themselves bazramit – 'the half-castes'", has historically not just been "fruitful", but also "difficult". He illustrates this through a biographical portray of Photini Poulou-Maistrelli's life as a "paradigm" for the latter. Poulou was born in Aweil to a Greek father and a Kreish mother from Raja in 1923. She spent most of her life in Wau and married a Greek merchant, but feuded both with other Bazramit and the community in Khartoum: for her and the descendants of other intermarriages "the main issue is to be recognized as Greek."[27]

Little is known about how the Greek community recovered after the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement and the establishment of the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region. Nicholas Ghines, who followed two uncles to settle in Equator in 1947 and set up a transport business, opened a safari hunting company in 1972.[19]

In 1994, the Hellenic Community of Khartoum took over the properties of the inactive communities in the South: the club and church in Juba were leased to the Catholic Archdiocese. "The same happened in Wau." However, when some Greeks returned to Wau in 1995, they managed to regain the community's estates.[1]

After the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the Greek Community of Juba registered officially again.[1] Prominent Greek-South Sudanese George Ghines writes that

"Notos Lounge Bar & Grill, the known Café-Restaurant in Juba today, called , is a prime example of the architecture of the first Greek settlers, coming from a region of Greece (the Greek part of Macedonia in Northern Greece today), producing excellent stone masons. The building was properly restored in 2009 and a lot of building elements were kept. It was built in the early 1900s by the Potamianos Family (a Cephalonian Greek), and owned by them until was bought by George N. Ghines in 2007 and begun the restoration works. The building was a warehouse storing wine & spirits, sugar, coal, rubber, trophies and imports from Europe, mainly Great Britain. It is the same building that the ex-US President Col. Theodore Roosevelt described in his memoires as he spent a night in the very same building."[citation needed]

Republic of South Sudan (since 2011)[edit]

In 2015, "the Divine Liturgy was celebrated for the first time after 38 years in St. Stylianos church in downtown Juba, by Metropolitan Narkissos of Nubia." Narkissos also laid the foundation stone for a new missionary center in Mongalla.[29] The Greek Orthodox Church (Patriarchate Alexandria) is a member of the South Sudan Council of Churches.[30]

According to Ghines,

"Today, there are still about 85 structures which are still in place and reminders of the glorious past of the Greeks in Juba, most notably the Greek Orthodox Church Aghios Stylianos, the new Greek Club, the Casino, houses, office buildings and of course the Cinema which has been converted into a Church."[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chaldeos, Antonis (2017). The Greek community in Sudan (19th-21st cen.). Athens. pp. 29, 111–116, 130–137, 147–155, 177, 210, 221–223, 242–243. ISBN 9786188233454.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kramer, Robert; Lobban, Richard; Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Sudan (4th ed.). Lanham / Toronto / Plymouth (UK): The Scarecrow Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-0-8108-6180-0.

- ^ a b Hill, Richard Leslie (1967). A Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan (2nd ed.). London: Frank Cass & Co. p. 163. ISBN 0-7146-1037-2.

- ^ Shinnie, Margaret. A Short History of the Sudan (Up to A.D. 1500). Khartoum: Sudan Antiquities Service. p. 8 – via Sudan Open Archive.

- ^ Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory. University of Rochester. p. 21. ISBN 1-58046-231-6.

- ^ a b c Chaldeos, Antonios (2017). "Sudanese toponyms related to Greek entrepreneurial activity". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4: Art. 1.

- ^ Ahmed, Hassan Abdel Aziz (1967). Caravan trade and routes in the northern Sudan in the 19th century: a study in historical geography. Durham: Durham University. p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Makris, Gerasimos; Stiansen, Endre (April 1998). "ANGELO CAPATO: A GREEK TRADER IN THE SUDAN" (PDF). Sudan Studies. 21. Sudan Studies Society of the United Kingdom (SSSUK): 10–18.

- ^ Antippas, Georges (2008). Pionniers méconnus du Congo Belge (in French). Bruxelles: éditions Masoin. pp. 54–57.

- ^ Katsigeras, Michalis (21 January 2009). "GREEKS IN THE CONGO". ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Leonardi, Cherry (2005). Knowing authority : colonial governance and local community in Equatoria Province, Sudan, 1900–1956 (Doctoral). Durham University. p. 98.

- ^ Deng, Francis Mading; Daly, M. W. (1989). Bonds of Silk: The Human Factor in the British Administration of the Sudan. Michigan State University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Ding, Daniel Thabo Nyibong (2005). The Impact of Change Agents on Southern Sudan History, ١٨٩٨ – ١٩٧٣. Khartoum: Institute of African and Asian Studies Graduate College University of Khartoum.

- ^ a b Santandrea, Stefano (1977). A popular history of Wau: (Bahr el Ghazal – Sudan) from its foundation to about 1940. Rome. pp. 46, 71 – via Sudan Open Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b CORMACK, ZOE TROY (2014). The Making and Remaking of Gogrial: Landscape, history and memory in South Sudan (PDF) (Doctoral). Durham: Durham University. pp. 175, 216.

- ^ Fefopoulou, Alexandra (March 2016). "The role of the Greek Orthodox religion in the construction of ethnic identity among the Greek community of Lubumbashi, DRC". Proceedings Ekklesiastikos Pharos. 2014 (1): 116 – via Sabinet.

- ^ Nakao, Shuichiro (2013). "A History from Below: Malakia in Juba, South Sudan, c. 1927–1954". The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies. 31: 139–160 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Tuttle, Brendan (2021-03-11). "To The Juba Wharf". Juba in the Making. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ a b "The 146th tribe of Sudan" (PDF). InSUDAN. UNMIS: 14–15. July 2010.

- ^ O'Balance, Edgar (2000). Sudan, Civil War and Terrorism, 1956–99. Springer. p. 21.

- ^ "29 Jailed and 34 Acquitted In Sudan Terrorist Trials". The New York Times. Reuters. March 4, 1964. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "1965 Mideast Mirror. 17". Arab News Agency.

- ^ McCall, Storrs. Manuscript on the history of the first civil war in South Sudan (Anya-Nya). Sudan Open Archive. p. 77.

- ^ Nadin, Alex (2005). "Greek merchant's shop, Gogrial". Collections from Southern Sudan at the Pitt Rivers Museum. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Khalid, Mansour (2003). War and Peace in Sudan: A Tale of Two Countries. Routledge. p. 113.

- ^ "Negritude and Progress". Voice of Southern Sudan. II (4). Sudan African National Union. 17 February 1965 – via Sudan Open Archive.

- ^ a b Tsakos, Alexandros (2009). Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette; Tsakos, Alexandros (eds.). The Agarik in Modern Sudan – A Narration Dedicated to Niania-Pa and Mahmoud Salih. Bergen: BRIC – Unifob Global & Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Bergen. pp. 115–129. ISBN 978-82-7453-079-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Hadjigeorgiou, Georgia (February 16, 2017). "300 του Λεωνίδα" στο Χαρτούμ, εκ Πλωμαρίου σύζυγος πρόεδρου και ο Ελληνικός Σύλλογος". The National Herald (in Greek). Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Revival of Orthodoxy in South Sudan". Orthodox Missionary Fraternity. 13 January 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "South Sudan Council of Churches". oikoumene. Retrieved 17 August 2018.