First Impressionist Exhibition

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Cover of the catalog of the First Impressionist Exhibition | |

| Native name | Première exposition des peintres impressionnistes |

|---|---|

| Date | April 15 – May 15, 1874 |

| Venue | 35 Boulevard des Capucines |

| Location | Paris, France |

| Also known as | The Exhibition of the Impressionists |

| Type | Art exhibition |

| Organized by | Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc. |

The First Impressionist Exhibition was an art exhibition held by the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.,[a] a group of nineteenth-century artists who had been rejected by the official Paris Salon and pursued their own venue to exhibit their artworks. The exhibition was held in April 1874 at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, the studio of the famous photographer Nadar. The exhibition became known as the "Impressionist Exhibition" following a satirical review by the art critic Louis Leroy in the 25 April 1874 edition of Le Charivari entitled "The Exhibition of the Impressionists". Leroy's article was the origin of the term Impressionism.

History[edit]

Background[edit]

In mid-19th century France, artists depended on public exhibitions to connect them with patrons willing to buy their artworks. The most prestigious exhibition was the Salon in Paris. From the earliest Salons in the 17th century until the French Revolution in 1789, only members of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture were permitted to exhibit artworks. Following the revolution and the abolishment of the Royal Academy in 1791, non-member artists were permitted to exhibit artworks in the Salon. With the exception of a short period of a few years following the French Revolution of 1848, the artworks displayed at the Salon were chosen by a jury consisting of members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.[1] Being accepted to the Salon was vital for artists because the jury's decision affected the public's perception of artworks. Paintings that had been accepted by the Salon were more likely to sell, and the public would often refuse to purchase paintings that had been rejected. Patrons would sometimes even return paintings that had been purchased beforehand if they had been rejected by the jury.[2] Artists who were rejected by the jury often complained about corruption and unfairness.[3] Disagreements among artists with the official standards of the Salon and the Académie des Beaux-Arts would lead to artists seeking alternative venues for promoting their art.

The Salon of 1863 was particularly controversial with artists. A new rule was established that limited artists to three artworks each. The jury was also stricter than it had been in previous years, rejecting three-fifths of all submissions. Even artists who had been regularly admitted were rejected. Louis Martinet, who had previously displayed artworks rejected from the Salon in his gallery, did not room to host all of the rejected artists.[4] After hearing about the controversy, Emperor Napoleon III visited Palais de l'Industrie where the Salon was to be held and consulted with the president of the jury. Two days later, it was announced that there would be a second elective Salon, a Salon des Refusés ("Salon of the Refused"), to exhibit the rejected artworks.[5]

The artwork to attract the most visitors at the Salon des Refusés was the painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe by Édouard Manet.[6] Manet had painted it specifically for the Salon, and had hoped that it would bring him success.[7] When it was rejected, Manet chose to display it at the Salon des Refusés in hopes that the public would side with him against the jury and prove the jury wrong.[8] The painting proved to be controversial with among critics. Many critics criticized it for the indecency of its subject matter. Manet was also widely criticized for painting technique, which some critics considered sloppy. Despite this criticism, other critics lauded his technique, and described it as "fresh" and "lively".[9][10] The scandal surrounding Édouard Manet and the Salon des Refusés brought several younger artists into his social circle.[11]

Manet was a frequent visitor at the Café Guerbois, located at 11 Grande rue des Batignolles in Paris. There he regularly met with many of his admirers, friends, and fellow artists. Some of the artists that regularly visited the café were Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cézanne. Émile Zola and Edmond Maître were also occasional visitors. The famous photographer Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, better known by his pseudonym Nadar, also sometimes visited the café.[12] The artists that frequented the Café Guerbois called themselves the Batignolles group. They chose to refer to themselves as a "group" rather than a "school" because, although they all had contempt for "official art", they all sought their own directions.[13]

The members of the Batignolles group had differing opinions about the Salon. Manet and Renoir believed that the Salon offered them the best chance at gaining recognition. Cézanne, on the other hand, believed that they should always submit their most "offensive" pictures to the Salon as a means of challenging established customs.[14] Despite their differing views, the members of the Batignolles group regularly submitted their artworks to that annual Salon. All members of the group except for Cézanne had been accepted into the Salon at least once.[15]

The Exhibition of the Impressionists[edit]

Claude Monet and Frédéric Bazille first proposed that the Batignolles group hold their own exhibition at their own expense in 1867. The group was unable to hold an exhibition then due to a lack of funds. Following the Salon of 1873 and the Exposition artisique des oeuvres refusées, a second Salon des Refusés, Monet once again proposed that the group hold their own exhibition. Bazille, who had died in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, did not live to participate in the exhibition that he and Monet had once envisioned.[16][17]

Edgar Degas expressed concern that if the exhibition only consisted of members of their own group, their exhibition might be seen by the public and critics as being put on by refusés and suggested that they invite outside artists and artists who had previously had success in the salon.[18][19] Some of the artists thought that inviting outsiders would change the character of the exhibition. Pierre-Auguste Renoir endorsed Degas's plan to invite outside artists, as a greater number of participating artists would result in a lower cost to each artist. The rest then agreed to Degas's plan.[20] Some of the members of the group opposed Cézanne's participation in the exhibition, however they agreed after Monet supported his participation. Manet would ultimately not participate in the exhibition. He once told the others that it was because he would never participate in an exhibition with Cézanne, however, his main reason was that believed that the only way to succeed was to succeed at the Salon.[21]

For the location of the group exhibition, Manet suggest the studio of the photographer Félix Nadar at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, which was sometimes rented out for concerts or lectures. Nadar had recently vacated his studio for a larger one at 51 rue d'Anjou nearby, so it was available for the group to use.[22] Nadar's studio was on the second floor of the building. A staircase led up to a series of large rooms on two floors which received light from the windows.[23] While Nadar preferred more tradition styles of art, he sympathized with the group's anti-establishment stance.[22] According to Monet, Nadar allowed the group to use his studio for free.[23]

On Pissarro's suggestion, the group formed a joint-stock company. The charter was signed on December 27, 1873. The initial signers of the charter were Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, Berthe Morisot, Pissarro, Béliard, Guillaumin, Lepic, Levert, and Rourt.[24] For the name of the group, Renoir and Degas wanted neutral name that would not be associated with a particular style or suggest a new "school" of art.[23][25] Degas suggested that the group be called La Capucine after their exhibition space at 35 Bouleveard des Capucines, with a capucine flower as their logo.[23][26] In the end, the members of group settled on the name Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.[a][25]

The Première exposition of the Société anonyme opened on April 15, 1874. They chose to open the exhibition two weeks before the Salon of 1874 in hopes of emphasizing to the public that it was not another Salon des Refusés.[27] The exhibition was open for one month, from ten in the morning to six in the evening. It was also open from eight to ten in the evening. The entrance fee was one franc, and the catalog was sold for fifty centimes.[28] Throughout its entire duration, the exhibition received about 3,500 visitors in total. This was significantly fewer than the Salon of 1874, which received about 400,000 visitors in total.[29] Most of the media coverage of exhibition came from left-wing and republican publications. Most of the conservative press chose not to provide platform to those who opposed official arts policy.[30]

On April 25, the satirical magazine Le Charivari published a review of the exhibition by Louis Leroy titled "L'Exposition des impressionnistes".[b] The satirical review was written in the form of a dialog between Leroy and a fictional[31] academic landscape painter named Joseph Vincent. In the review, as Leroy guides Vincent through the exhibition, Vincent is shocked and aghast at style of the paintings. Leroy begrudgingly defends each painting by saying that, while they are not accurate depictions, they have an impression of what they are supposed to depict. Vincent repeatedly mocks Leroy's use of the word "impression", and begins to refer to the artists collectively as "impressionists". When Vincent finally reaches Cézanne's A Modern Olympia, he is driven mad at its sight and begins to hallucinate that the paintings are talking to him.[32] Leroy's article was intended to be just as much of a spoof of the reactions of conservative academic painters to the "Impressionists" as it was a mockery of Impressionists themselves.[33]

Louis Leroy's review was the first use of the term "Impressionists", a term that would come to refer to the artists who painted in style of Impressionism. Leroy's use of the word "impression" derived from the title of Claude Monet's painting Impression, Sunrise. Monet chose to call his painting an "impression" after Edmond Renoir (the brother of Pierre-Auguste Renoir), the editor of the exhibition catalog, complained that the titles of his paintings were too monotonous. Monet told him "Why don't you just put Impression!"[28] Critics had sometimes previously used the term "impression" in reference to the landscape paintings of Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Johan Jongkind. The members of the Batignolles group had also previously used the term "impression" in reference to creating "impressions of nature".[34]

The First Impressionist Exhibition was a commercial failure. Money earned from entrance fees, catalog sales, commissions on painting sales, etc. amounted to 10,221.50 francs. Expenses from rent, decorations, insurance, wages, etc. amounted to 9,272.20 francs. The remaining 949.20 francs were added to 2,359.50 in outstanding shares. In December of 1874, Renoir called a meet where he announced that, after paying off all debts, the Société anonyme still owed over 3,700 francs in liabilities, but only had about 278 francs remaining. All of the members still owed about 185 francs each. The group was then liquidated, and members that had already paid their dues for the next year were refunded.[35]

Legacy[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

Despite the commercial and critical failure of the First Impressionist Exhibition and the Société anonyme, the Impressionists would not be dissuaded from pursuing their own style and would hold seven more Impressionist Exhibitions. A second exhibition was held in 1876, a third 1877, a fourth in 1879, a fifth in 1880, a sixth 1881, a seventh in 1882, and an eight and final exhibition was held in 1886.[36]

Commemorative exhibitions[edit]

In 1974, the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art held an exhibition titled Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition to celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of the first Impressionist exhibition. The goal of the exhibition was to exhibit some of the most significant Impressionist works that were painted from approximately 1860 thorough the late 1880s.[37] Forty-two paintings were included in the exhibition. The version of the exhibition held at the MET included additional galleries of other contemporaneous paintings to help put the Impressionist paintings in context as well as later Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings.[38]

Reception[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

Much of the critical reception to the First Impressionist Exhibition was negative. Many of the critics commented that the paintings looked unfinished.[40]

Participating artists[edit]

The exhibition catalog lists thirty artists as participated in the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.[41] A thirty-first artist, the Comtesse de Luchaire, was mentioned as participating in the exhibition in a review by Marc de Montifaud, but was not listed among the participating artists in the catalog.[42][43]

- Zacharie Astruc

- Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu

- Édouard Béliard

- Eugène Boudin

- Félix Bracquemond

- Jacques Émile Édouard Brandon

- Pierre-Isidore Bureau

- Adolphe-Félix Cals

- Paul Cézanne

- Gustave-Henri Colin

- Louis Debras

- Edgar Degas

- Armand Guillaumin

- Louis Latouche

- Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic

- Stanislas Lépine

- Léopold Levert

- Comtesse de Luchaire

- Alfred Meyer

- Auguste de Molins

- Claude Monet

- Berthe Morisot

- Émilien Mulot-Durivage

- Giuseppe De Nittis

- Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin

- Léon-Auguste Ottin

- Camille Pissarro

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir

- Léopold Robert

- Henri Rouart

- Alfred Sisley

List of artworks[edit]

The exhibition catalog for the First Impressionist Exhibition lists artworks as numbered 1 through 165. Several of these entries contain multiple artworks each, and there are no entries listed for numbers 71, 72, and 73.[41] Three artworks were shown at the exhibition hors catalogue ("out of catalog"), meaning that they were exhibited but were not listed in the catalog. These artworks have been identified as being displayed at the exhibition through references in contemporary reviews.[44][45] These hors catalogue artworks are numbered as "HC#" in the list below.

| No. | Title | Image | Artist | Date | Technique | Dimensions | Current Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Le Bouquet à la Pénitente | Zacharie Astruc | Watercolor | |||||

| 2. | La Leçon du vieux Torrero | Zacharie Astruc | Watercolor | |||||

| 3. | Frame of figures containing:

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | Watercolor on paper | 38 cm × 55 cm (15 in × 22 in) | Private collection | [46] | |||

| Zacharie Astruc | 1874 | Watercolor on vellum paper | 36.4 cm × 28.4 cm (14.3 in × 11.2 in) | Musée d'Évreux | [47][48] | ||

| 4. | Frame of landscapes containing:

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||||

| Zacharie Astruc | ||||||||

| 5. | Les Poupées blanches (Japon) | Zacharie Astruc | ||||||

| 6. | Le Ménage mal assorti | Zacharie Astruc | ||||||

| 7. | Nature morte | Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu | ||||||

| 8. | Un fin Connaisseur | Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu | ||||||

| 9. | Quelques réflexions (au XIIIe arrondissement) | Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu | ||||||

| 11. | Nature morte: Cuisine | Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu | Watercolor | |||||

| 12. | Nature morte: Cuisine | Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu | Watercolor | |||||

| 13. | Le Fort de la Halle | Édouard Béliard | ||||||

| 14. | Saules | Édouard Béliard | ||||||

| 15. | Rue de l'Hermitage, à Pontoise | Édouard Béliard | ||||||

| 16. | Vallée d'Auvers | Édouard Béliard | ||||||

| 17. | Le Toulinguet, côtes de Camaret (Finistère) | Eugène Boudin | ||||||

| 18. | The Coast of Portrieux, Cotes-du-Nord |  | Eugène Boudin | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 85 cm × 148 cm (33 in × 58 in) | Private collection | [i][49] |

| 19. | The Coast of Portrieux, Cotes-du-Nord | Eugène Boudin | See above. | |||||

| 20. | 4 Cadres (même numéro). Études de ciel ("4 Frames (same number). Sky studies") | Eugène Boudin | Pastels | |||||

| 21. | 2 Cadres (même numéro). Études diverses ("4 Frames (same number). Various studies") | Eugène Boudin | Pastels | |||||

| 22. | 4 Cadres (même numéro). Plage de Trouville ("4 Frames (same number). Trouville Beach") | Eugène Boudin | Watercolors | |||||

| 23. | Portrait | Félix Bracquemond | Drawing | |||||

| 24. | Frame of etchings: Portraits of MM.

|  | Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 33 cm × 23 cm (13.0 in × 9.1 in) | [47] | ||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 21.8 cm × 24.5 cm (8.6 in × 9.6 in) | [47] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 27.5 cm × 10 cm (10.8 in × 3.9 in) | [47] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 16.4 cm × 14.5 cm (6.5 in × 5.7 in) | [47] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 19 cm × 13.5 cm (7.5 in × 5.3 in) | New York Public Library | [50] | |||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 22.8 cm × 13.5 cm (9.0 in × 5.3 in) | [50] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 17 cm × 11.5 cm (6.7 in × 4.5 in) | [50] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 12 cm × 8.8 cm (4.7 in × 3.5 in) | [50] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 15.4 cm × 12.1 cm (6.1 in × 4.8 in) | [51] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 15.4 cm × 9.8 cm (6.1 in × 3.9 in) | [51] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 10.5 cm × 7 cm (4.1 in × 2.8 in) | [52] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 24.5 cm × 16.2 cm (9.6 in × 6.4 in) | [52] | ||||

| 25. | Frame of etchings: |  | Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 20.2 cm × 26.3 cm (8.0 in × 10.4 in) | [52] | ||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 17.9 cm × 25 cm (7.0 in × 9.8 in) | [52] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 22.1 cm × 32.4 cm (8.7 in × 12.8 in) | Cabinet des estampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France | [52] | |||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 27.2 cm × 39.5 cm (10.7 in × 15.6 in) | [52] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 31.3 cm × 16.2 cm (12.3 in × 6.4 in) | [53] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 14.3 cm × 22.8 cm (5.6 in × 9.0 in) | [53] | ||||

| 26. | Frame of etchings:

|  | Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 20.3 cm × 29.5 cm (8.0 in × 11.6 in) | [53] | ||

| (No free image) | Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 14 cm × 31.7 cm (5.5 in × 12.5 in) | [53] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | |||||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 21.3 cm × 15.2 cm (8.4 in × 6.0 in) | [53] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 10 cm × 31 cm (3.9 in × 12.2 in) | [53] | ||||

| (No free image) | Félix Bracquemond | Drypoint | 23 cm × 31 cm (9.1 in × 12.2 in) | [54] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Drypoint | 25 cm × 34.9 cm (9.8 in × 13.7 in) | [55] | ||||

| 27. | Frame of engravings:

|  | Félix Bracquemond | Etching and aquatint | 21.5 cm × 23 cm (8.5 in × 9.1 in) | [56] | ||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 18 cm × 12 cm (7.1 in × 4.7 in) | [56] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 24 cm × 21 cm (9.4 in × 8.3 in) | [56] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 16.1 cm × 11 cm (6.3 in × 4.3 in) | [56] | ||||

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 16 cm × 22.5 cm (6.3 in × 8.9 in) | [57] | ||||

| 28. | Frame of engravings:

|  | Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 24.8 cm × 19.7 cm (9.8 in × 7.8 in) | Unknown | [57] | |

| Félix Bracquemond | Etching | 24.8 cm × 19.7 cm (9.8 in × 7.8 in) | [57] | ||||

| 29. | Scene in a Synagogue |  | Jacques Émile Édouard Brandon | 1869-70 | Oil on canvas | 156.9 cm × 88.3 cm (61.8 in × 34.8 in) | Philadelphia Museum of Art | [57] |

| 30. | Portrait de M. A. Z. | Jacques Émile Édouard Brandon | ||||||

| 31. | Watercolors | Jacques Émile Édouard Brandon | Watercolors | |||||

| 32. | Exposition du corps de Sainte-Brigitte à Rome, en 1392 | Jacques Émile Édouard Brandon | ||||||

| 32. (bis) | Le Maître d'ecole | (No free image) | Jacques Émile Édouard Brandon | Lithograph | 16 cm × 21 cm (6.3 in × 8.3 in) | Cabinet des estampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France | [58] | |

| 33. | Le Clocher de Jouy-le-Comte | Pierre-Isidore Bureau | ||||||

| 34. | Près de l'étang de Jouy-le-Comte | Pierre-Isidore Bureau | ||||||

| 35. | Moonlight on the banks of the Oise in Isle-Adam |  | Pierre-Isidore Bureau | 1867 | Oil on canvas | 33 cm × 41 cm (13 in × 16 in) | Musée d'Orsay | [59] |

| 35. (bis) | Clair-de-Lune | Pierre-Isidore Bureau | ||||||

| 36. | Portrait de Madame Ed. G. | Adolphe-Félix Cals | ||||||

| 37. | Le Bon Père Pêcheur à Honfleur | (No free image) | Adolphe-Félix Cals | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 120 cm × 100 cm (47 in × 39 in) | Unknown | [60] |

| 38. | Vieux pêcheur |  | Adolphe-Félix Cals | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 115.9 cm × 88.9 cm (45.6 in × 35.0 in) | Private collection | [60] |

| 39. | Paysage | Adolphe-Félix Cals | ||||||

| 40. | Bonne Femme tricotant | Adolphe-Félix Cals | ||||||

| 41. | La Fileuse bleue | (No free image) | Adolphe-Félix Cals | 1860 | Oil on canvas | 39 cm × 30 cm (15 in × 12 in) | Unknown | [60] |

| 42. | The Hanged Man's House |  | Paul Cézanne | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 55 cm × 66 cm (22 in × 26 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [61] |

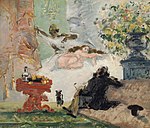

| 43. | A Modern Olympia |  | Paul Cézanne | 1873-74 | Oil on canvas | 46.2 cm × 55.5 cm (18.2 in × 21.9 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [62] |

| 44. | Étude: Paysage à Auvers |  | Paul Cézanne | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 46.3 cm × 55.2 cm (18.2 in × 21.7 in) | Philadelphia Museum of Art | [63] |

| 45. | Haurra-Maria | Gustave-Henri Colin | ||||||

| 46. | La Maison du Charpentier | Gustave-Henri Colin | ||||||

| 47. | L'Étang aux poules d'eau | Gustave-Henri Colin | ||||||

| 48. | Marchandes de poissons de Fontarabie (Espange) | Gustave-Henri Colin | ||||||

| 49. | Entrée du port de Pasages (Espange) | Gustave-Henri Colin | ||||||

| 50. | Un Paysan | Louis Debras | ||||||

| 51. | Une Nature morte | Louis Debras | ||||||

| 52. | San Juan de la Rapita (Espagne) | Louis Debras | Drawing | |||||

| 53. | Rembrandt dans son atelier | Louis Debras | ||||||

| 54. | Examen de danse au théâtre | Edgar Degas | ||||||

| 55. | The Dancing Class |  | Edgar Degas | 1871 | Oil on wood | 19.7 cm × 27 cm (7.8 in × 10.6 in) | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York | [64] |

| 56. | Intérieur de coulisse | Edgar Degas | Destroyed by artist | [65] | ||||

| 57. | Blanchisseuse | Edgar Degas | ||||||

| 58. | Départ de Course | Edgar Degas | Sketch drawing | |||||

| 59. | Faux Départ | Edgar Degas | Drawing | |||||

| 60. | Ballet Rehearsal on Stage |  | Edgar Degas | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 65 cm × 81.5 cm (25.6 in × 32.1 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [66][ii] |

| 61. | Une Blanchisseuse |  | Edgar Degas | 1869 | Charcoal, white chalk, and pastel on paper | 74 cm × 61 cm (29 in × 24 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [66] |

| 62. | Après le bain | Edgar Degas | Drawing | |||||

| 63. | At the Races in the Countryside |  | Edgar Degas | 1869 | Oil on canvas | 36.5 cm × 55.9 cm (14.4 in × 22.0 in) | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | [70] |

| 64. | View of the Seine, Paris |  | Armand Guillaumin | 1871 | Oil on canvas | 126.4 cm × 181.3 cm (49.8 in × 71.4 in) | Museum of Fine Arts, Houston | [71] |

| 65. | Temps pluvieux (landscape) | Armand Guillaumin | ||||||

| 66. | Soleil couchant à Ivry |  | Armand Guillaumin | 1869 | Oil on canvas | 65 cm × 81 cm (26 in × 32 in) | Musée d'Orsay | [72] |

| 67. | Clocher de Berk (pas-de-Calais) | Louis Latouche | ||||||

| 68. | Vue des Quais (Paris) | Louis Latouche | ||||||

| 69. | La Plage, marée basse à Berck (Pas-de-Calais) | Louis Latouche | ||||||

| 70. | Sous bois | Louis Latouche | ||||||

| 74. | L'Arrivée de la marée à Cayeux | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | Watercolor | |||||

| 75. | La pêche | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | Watercolor | |||||

| 76. | Golfe de Naples | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | Watercolor | |||||

| 77. | Le Départ pour la pêche du hareng | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | Etching | |||||

| 78. | L'Escalier du château d'Aix en Savoie | (No free image) | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | 1863 | Etching | 41 cm × 38.4 cm (16.1 in × 15.1 in) | [73] | |

| 79. | César, Portrait de chien |  | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | 1861 | Etching | 32 cm × 24 cm (12.6 in × 9.4 in) | [73] | |

| 80. | Jupiter, Portrait de chein |  | Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic | 1861 | Etching | 34.5 cm × 25.5 cm (13.6 in × 10.0 in) | [73] | |

| 81. | Le canal Saint-Denis | Stanislas Lépine | ||||||

| 82. | La rue Cortot | Stanislas Lépine | ||||||

| 83. | Bank of the Seine |  | Stanislas Lépine | 1869 | Oil on canvas | 30 cm × 58.5 cm (11.8 in × 23.0 in) | Musée d'Orsay | [74] |

| 84. | Bords de l'Essonne | Léopold Levert | ||||||

| 85. | Le Moulin de Touiaux | Léopold Levert | ||||||

| 86. | Près d'Auvers | Léopold Levert | ||||||

| HC1 | Lieutenant des lanciers | Comtesse de Luchaire | [iii][42] | |||||

| 87. | Estienne Marcel, prévôt des marchands | Alfred Meyer | Enamel | |||||

| 88. | Doña Maria Pacheco, épouse de Don Jaun de Padilla, chef de l'insurrection, qui avait pris le nom de Sainte Ligue des communes sous Charles-Quint | Alfred Meyer | Enamel | |||||

| 89. | Le Firmament | Alfred Meyer | Enamel | |||||

| 90. | Figure d'après Raphaël | Alfred Meyer | Enamel | |||||

| 91. | Figure d'après Raphaël | Alfred Meyer | Enamel | |||||

| 91. (bis) | Idylle | Alfred Meyer | Drawing | |||||

| 92. | The Comming Storm | (No free image) | Auguste de Molins | 1874 | Oil on panel | 34.6 cm × 55.5 cm (13.6 in × 21.9 in) | Private collection, Lausanne | [75] |

| 93. | Rendez-Vous de chasse | (No free image) | Auguste de Molins | Oil on canvas | 35.5 cm × 55 cm (14.0 in × 21.7 in) | Private collestion | [iv][75] | |

| 94. | Relai de chiens | Auguste de Molins | ||||||

| 94. (bis) | Rendez-Vous de chasse | Auguste de Molins | ||||||

| 95. | Poppies at Argenteuil |  | Claude Monet | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 50 cm × 65 cm (20 in × 26 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [76] |

| 96. | Fishing Boats Leaving the Port of Le Havre |  | Claude Monet | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 60 cm × 101 cm (24 in × 40 in) | Private collection | [77] |

| 97. | Boulevard des Capucines |  | Claude Monet | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 61 cm × 80 cm (24 in × 31 in) | Pushkin Museum, Moscow | [78][v] |

| 98. | Impression, Sunrise |  | Claude Monet | 1872 | Oil on canvas | 48 cm × 63 cm (19 in × 25 in) | Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris | [81][82] |

| 99. | Deux croquis ("Two sketches") | Claude Monet | Pastel | |||||

| 100. | Deux croquis ("Two sketches") | Claude Monet | Pastel | |||||

| 101. | Deux croquis ("Two sketches") | Claude Monet | Pastel | |||||

| 102. | Un croquis ("A sketch") | Claude Monet | Pastel | |||||

| 103. | The Luncheon |  | Claude Monet | 1868-69 | Oil on canvas | 150 cm × 230 cm (59 in × 91 in) | Städel Museum, Frankfurt | [83] |

| 104. | The Cradle |  | Berthe Morisot | 1872 | Oil on canvas | 56 cm × 46 cm (22 in × 18 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [84] |

| 105. | La lecture |  | Berthe Morisot | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 45.1 cm × 72.4 cm (17.8 in × 28.5 in) | Cleveland Museum of Art | [85][86] |

| 106. | Hide-and-Seek |  | Berthe Morisot | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 45 cm × 55 cm (18 in × 22 in) | Private collection, New York | [87] |

| 107. | The Harbor at Lorient |  | Berthe Morisot | 1869 | Oil on canvas | 43.5 cm × 73 cm (17.1 in × 28.7 in) | National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC | [88] |

| 108. | Portrait of Madeleine Thomas |  | Berthe Morisot | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 60 cm × 49.5 cm (23.6 in × 19.5 in) | Private collection, New York | [89] |

| 109. | Le village de Maurecourt |  | Berthe Morisot | Pastel on paper | 47 cm × 72 cm (19 in × 28 in) | Private collection, New York | [90] | |

| 110. | Sur la falaise |  | Berthe Morisot | Watercolor on paper | 18 cm × 23 cm (7.1 in × 9.1 in) | Musée d'Orsay | [91] | |

| 111. | Jeune Femme et enfant sur un banc |  | Berthe Morisot | Watercolor on paper | 33 cm × 23 cm (13.0 in × 9.1 in) | Musée d'Orasy | [91] | |

| 112. | Femme et enfant assise dans un pré |  | Berthe Morisot | Watercolor on paper | 21 cm × 24.1 cm (8.3 in × 9.5 in) | Private collection | [91] | |

| HC2 | Portrait of Madame Pontillon |  | Berth Morisot | 1871 | Pastel on paper | 81 cm × 65 cm (32 in × 26 in) | Musée d'Orasy | [vi][92] |

| 113. | Barques à plomb | Mulot-Durivage | ||||||

| 114. | La Rampe | Mulot-Durivage | ||||||

| 115. | Paysage près de Blois | Giuseppe De Nittis | ||||||

| 116. | Lever de Lune. Vésuve | Giuseppe De Nittis | ||||||

| 117. | Campagne du Vésuve | Giuseppe De Nittis | ||||||

| 118. | Études de femme | Giuseppe De Nittis | ||||||

| 118. (bis) | Route en Italie | Giuseppe De Nittis | ||||||

| 119. | Amour et Psyché | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Marble group | |||||

| 120. | Acis et Galathée |  | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Bronze reduction | Unknown | [vii][93] | ||

| 121. | Jeune Faune |  | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Bronze reduction | Unknown | [viii][93] | ||

| 122. | Nymphe chasseresse |  | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Bronze reduction | Unknown | [ix][93] | ||

| 123. | Jeune Femme portant un vase | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Terracotta | |||||

| 124. | Jeune Femme portant un vase | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Terracotta | |||||

| 125. | Buste | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Terracotta | |||||

| 126. | Buste de Ingress |  | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | 1840 | Plaster reduction | 53 cm (21 in) | Musée Ingres, Montauban | [x][93] |

| 127. | Le Dernier Mousse du Vengeur | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Plaster | |||||

| 128. | Buste de M. B*** | Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin | Terracotta | |||||

| 129. | Après la messe à la campagne | Léon-Auguste Ottin | ||||||

| 130. | Au Château (sannois) | Léon-Auguste Ottin | ||||||

| 131. | La Butte Montmartre, versant sud | Léon-Auguste Ottin | ||||||

| 132. | La Fête chez Thérèse | Léon-Auguste Ottin | Watercolor | |||||

| 133. | Une Bergerie sans moutons | Léon-Auguste Ottin | Lithograph | |||||

| 134. | At home | Léon-Auguste Ottin | ||||||

| 135. | Marette | Léon-Auguste Ottin | ||||||

| 136. | Orchard in Bloom, Louveciennes |  | Camille Pissarro | 1872 | Oil on linen | 45.1 cm × 54.9 cm (17.8 in × 21.6 in) | National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC | [95] |

| 137. | Hoarfrost |  | Camille Pissarro | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 65.5 cm × 93 cm (25.8 in × 36.6 in) | Musée d'Orsay, Paris | [96] |

| 138. | The Chestnut Trees at Osny |  | Camille Pissarro | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 65 cm × 81 cm (26 in × 32 in) | Private collection, New York | [97] |

| 139. | The Public Garden at Pontoise |  | Camille Pissarro | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 60 cm × 73 cm (24 in × 29 in) | Metropolitan Museum of Art | [98] |

| 140. | June Morning at Pontoise |  | Camille Pissarro | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 55 cm × 91 cm (22 in × 36 in) | Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe | [98] |

| 141. | The Dancer |  | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 142.5 cm × 94.5 cm (56.1 in × 37.2 in) | National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC | [99] |

| 142. | La Loge, ("The Theatre Box") |  | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 80 cm × 63.5 cm (31.5 in × 25.0 in) | Courtauld Gallery, London | [100] |

| 143. | La Parisienne |  | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | 1874 | Oil on canvas | 163.2 cm × 108.3 cm (64.3 in × 42.6 in) | Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales | [100][101] |

| 144. | Harvesters |  | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 58 cm × 72.5 cm (22.8 in × 28.5 in) | Private collection | [100] |

| 145. | Mixed Flowers in an Earthenware Pot |  | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | 1869 | Oil on canvas | 64.8 cm × 54 cm (25.5 in × 21.3 in) | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | [100] |

| 146. | Croquis | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | Pastel | |||||

| 147. | Tête de femme | (No free image) | Pierre-Auguste Renoir | Oil on canvas | 32 cm × 24.1 cm (12.6 in × 9.5 in) | Unknown | [100] | |

| 148. | Ferme bretonne | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 149. | Levée d'étang | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 150. | Vue de Melun | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 151. | Village | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 152. | Forêt | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 153. | Route bretonne | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 154. | Ferme bretonne | Henri Rouart | Watercolor | |||||

| 155. | Maisons béarnaises | Henri Rouart | Watercolor | |||||

| 155. | Maisons béarnaises | Henri Rouart | Watercolor | |||||

| 157. | Eau-forte | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 158. | Eau-forte | Henri Rouart | ||||||

| 159. | Jeunes filles dans les foins en fleurs | Léopold Robert | ||||||

| 160. | Cadre | Léopold Robert | Watercolor | |||||

| 161. | The Route from Saint-Germain to Marly |  | Alfred Sisley | 1872 | Oil on canvas | 46.4 cm × 61 cm (18.3 in × 24.0 in) | McNay Art Museum | [102][103] |

| 162. | The Ferry of the Ile de la Loge Flood |  | Alfred Sisley | 1872 | Oil on canvas | 46 cm × 61 cm (18 in × 24 in) | Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen | [104] |

| 163. | The Machine at Marly |  | Alfred Sisley | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 45 cm × 64.5 cm (17.7 in × 25.4 in) | Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen | [105] |

| 164. | Orchard | (No free image) | Alfred Sisley | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 50 cm × 73 cm (20 in × 29 in) | Private collection, Paris | [106] |

| 165. | Port Marly, soiré d'hiver | Aldred Sisley | ||||||

| HC3 | Autumn: Banks of the Seine near Bougival |  | Alfred Sisley | 1873 | Oil on canvas | 46 cm × 62 cm (18 in × 24 in) | Montreal Museum of Fine Arts | [xi][107] |

Catalog notes[edit]

- ^ Two paintings by Boudin with identical titles are listed in the catalog of the first Impressionist Exhibition. Another painting by Boudin with an identical is listed in the catalog of the Salon of 1874. The painting listed here may have been one of the two shown at the Impressionist Exhibition, or it may have been the one shown at the Paris Salon.

- ^ There are two other versions of this painting in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These other two versions were probably painted after the Musée d'Orsay version.[67][68][69]

- ^ This artwork was shown at the exhibiton, but neither the artist nor the artwork were listed in the catalog.

- ^ This painting may have been either 93 or 94 (bis), as the two listings have identical titles.

- ^ Monet painted two paintings titled Boulevard des Capucines. It has been traditionally held that the version in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri was the version exhibited at the First Impressionist Exhibition. However, recent scholarship has suggested that it was the version that is currently in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, Russia.[79][80]

- ^ This artwork was shown at the exhibition, but was not listed in the catalog.

- ^ Catalog items 120, 121, and 122 were smaller bronze versions of Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin's marble sculptures made for the Medici Fountain in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. The current location of these bronze reductions is unknown. Pictured is the full-sized marble version of Acis et Galathée at the gardens, which is located at the center-bottom of the fountain.

- ^ Catalog items 120, 121, and 122 were smaller bronze versions of Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin's marble sculptures made for the Medici Fountain in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. The current location of these bronze reductions is unknown. Pictured is the full-sized marble version of Jeune Faune at the gardens, which is located in the left niche of the fountain.

- ^ Catalog items 120, 121, and 122 were smaller bronze versions of Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin's marble sculptures made for the Medici Fountain in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. The current location of these bronze reductions is unknown. Pictured is the full-sized marble version of Nymphe chasseresse at the gardens, which is located in the right niche of the fountain.

- ^ Pictured is the full-sized marble version. A Non-free photograph of the plaster version is available at the Musée Ingres website.[94]

- ^ This painting was shown at the exhibition, but was not listed in the catalog.

See also[edit]

- Salon des Indépendants — an annual art show held in Paris that began in 1884.

- Salon d'Automne — an annual art show held in Paris that began in 1903.

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Feist (2006), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 79.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), p. 14.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 79–80.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 80.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 85.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 81–82.

- ^ McCauley, Anne (1998). "Sex and the Salon: Defining Art and Immorality". In Tucker, Paul Hayes (ed.). Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–74. ISBN 0-521-47466-3.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 86.

- ^ Feist (2006), p. 64.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 197.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 205.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 214.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 216.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 302–304, 309.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), pp. 61–66.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 311–312.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 314–316.

- ^ a b Gosling, Nigel (1976). Nadar. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-394-41106-4.

- ^ a b c d Rewald (1973), p. 313.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b Moffett (1986), p. 18.

- ^ Feist (2006), p. 136.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), p. 74.

- ^ a b Rewald (1973), p. 318.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Feist (2006), p. 140.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), p. 80.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 318–324.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 117.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 212.

- ^ Rewald (1973), pp. 334–336.

- ^ Dunlop (1972), p. 87.

- ^ Dayez, Hoog & Moffet (1974), pp. 9–13.

- ^ Hoving, Thomas (1973). "[Director's Note]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 32 (3): 1. ISSN 0026-1521. JSTOR 3269130. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Schaefer, Saint-George & Lewerentz (2008), p. 158.

- ^ Schaefer, Saint-George & Lewerentz (2008), p. 159.

- ^ a b Moffett (1986), pp. 118–123.

- ^ a b Berson (1996), p. 9.

- ^ Dumas, Ann, ed. (2007). Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past. Denver: Denver Art Museum. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-914738-57-2.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 6.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. vii, 283.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e Berson (1996), pp. 3, 15.

- ^ "Intérieur Parisien". POP: la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine (in French). Ministrè de la Culture. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Dayez, Hoog & Moffet (1974), pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d Berson (1996), pp. 3, 16.

- ^ a b Berson (1996), pp. 4, 16.

- ^ a b c d e f Berson (1996), pp. 4, 17.

- ^ a b c d e f Berson (1996), pp. 4, 18.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 4, 19.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 4–5, 19.

- ^ a b c d Berson (1996), pp. 5, 19.

- ^ a b c d Berson (1996), pp. 5, 20.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 6–7, 20.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 6, 20.

- ^ a b c Berson (1996), pp. 6, 21.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 322.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 323.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 126.

- ^ Dayez, Hoog & Moffet (1974), pp. 94–98.

- ^ Berson (1996), p. 7.

- ^ a b Berson (1996), pp. 7, 22.

- ^ "Répétition d'un ballet sur la scène". Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "The Rehearsal Onstage". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 311.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 128.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 8, 22.

- ^ a b c Berson (1996), pp. 8, 23.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 129.

- ^ a b Berson (1996), pp. 9, 23.

- ^ Wildenstein (1996), pp. 117–18.

- ^ Wildenstein (1996), p. 126.

- ^ Wildenstein (1996), p. 125.

- ^ Lilley, Ed (2012). "A Rediscovered English Review of the 1874 Impressionist Exhibition". The Burlington Magazine. 154 (1317): 843–845. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 41812904. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Ian (March 2007). "Monet's Boulevard des Capucines: Kansas City or Moscow?". Apollo. 165 (541): 69–71. ISSN 0003-6536.

- ^ Wildenstein (1996), pp. 113–14.

- ^ Dayez, Hoog & Moffet (1974), pp. 150–154.

- ^ Wildenstein (1996), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 131.

- ^ Berson (1996), p. 10, 25.

- ^ "Reading". Cleveland Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 133.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 134.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 135.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 136.

- ^ a b c Berson (1996), pp. 10, 26.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. vii, 11, 26.

- ^ a b c d Berson (1996), pp. 11, 26.

- ^ Buste d'Ingres Archived 2024-01-27 at the Wayback Machine (In French)

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 137.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 138.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 139.

- ^ a b Berson (1996), pp. 12, 27.

- ^ Moffett (1986), p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e Berson (1996), pp. 12, 28.

- ^ "The blue lady". Museum Wales. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 13, 28.

- ^ "The Route from Saint-Germain to Marly". McNay Art Museum. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Shone (1999), pp. 62–64.

- ^ Shone (1999), pp. 64, 83.

- ^ Berson (1996), pp. 13, 29.

- ^ Moffett (1986), pp. 6, 142.

Bibliography[edit]

- Berson, Ruth (1996). The New Painting: Impressionism 1874-1886: Documentation. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. ISBN 0-295-96704-8.

- Dayez, Anne; Hoog, Michel; Moffet, Charles S. (1974). Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-097-7. Archived from the original on 2023-07-16. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- Dunlop, Ian (1972). The Shock of the New: Seven Historic Exhibitions of Modern Art. New York: American Heritage Press.

- Feist, Peter H. (2006). Impressionist Art, 1860-1920. Vol. 1. Köln, London, Los Angeles, Madrid, Paris, Tokyo: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5053-4.

- Moffett, Charles S. (1986). The New Painting: Impressionism 1874-1886. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. ISBN 0-88401-047-3.

- Rewald, John (1973). The History of Impressionism (Fourth ed.). New York: Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 0-87070-360-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - Schaefer, Iris; Saint-George, Caroline von; Lewerentz, Katja (2008). Painting Light: The hidden techniques of the Impressionists. Milan: Skira. ISBN 978-88-6130-609-7.

- Shone, Richard (1999). Sisley (Revised paperback ed.). London: Phaidon Press Limited. ISBN 0-7148-3892-6.

- Wildenstein, Daniel (1996). Monet: Catalogue Raisonné. Vol. II. Köln: Taschen, Wildenstein Institute. ISBN 3-8228-8759-5.

External links[edit]

- The Exhibition catalog (in French) for the Première Exposition 1874 at the Bibliothèque nationale de France's Digital Library.

- Louis Leroy's review L'Exposition des impressionnistes (in French) at the Bibliothèque nationale de France's Digital Library.