Cuarteto Zupay

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Cuarteto Zupay | |

|---|---|

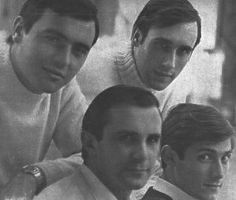

First line-up of Cuarteto Zupay in 1967. Top: Aníbal López Monteiro and Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Bottom: Eduardo Vittar Smith and Juan José García Caffi (from left to right). | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | |

| Genres |

|

| Years active | 1966-1991 |

| Members | Until disbandment: |

| Past members | |

Cuarteto Zupay or simply Los Zupay, was an Argentinian Popular Music group formed in Buenos Aires in 1966 that remained active until 1991. The founding members were the brothers Pedro Pablo García Caffi (baritone) and Juan José García Caffi (first tenor), Eduardo Vittar Smith (bass) and Aníbal López Monteiro (second tenor).

Over the years, the group's line-up changed with the exception of Pedro Pablo García Caffi, holder of the group's name, who remained a member until its dissolution. Other members were Eduardo Cogorno (tenor), Rubén Verna (tenor), Horacio Aragona (tenor), Gabriel Bobrow (tenor), Javier Zentner (bass) and Marcelo Díaz (tenor). From 1981 until the dissolution of the quartet in 1991, the line-up was Pedro Pablo García Caffi, Eduardo Vittar Smith, Rubén Verna and Gabriel Bobrow.

With a style based on vocal work, Cuarteto Zupay tried to overcome the split between folkloric music and tango, as well as to develop new sounds and themes that could attract young people to a style they called Música Popular Argentina (English: Argentinian Popular Music) or MPA.

Among their repertoire stand out Marcha de San Lorenzo, Zamba del nuevo día, Chiquilín de Bachín, Si Buenos Aires no fuera así, Jacinto Chiclana, Canción de cuna para un gobernante, Oración a la Justicia, Como la cicada, Te quiero, Ojalá, etc.

Their favorite author was María Elena Walsh, whose songs were included in almost all the albums they released, three of them exclusively.

Background[edit]

In Argentina, folk music had been growing in popularity since the 1930s, hand in hand with a process of industrialization that induced a massive internal migration from the countryside to the city and from the provinces to the capital, Buenos Aires. This resurgence of traditional folk music exploded in the 1950s in what was called the "boom del folklore" (English: folklore boom).

In the 1960s, the folklore boom was amplified with the creation of the major folklore music festivals such as the Cosquín Folk Festival (1961) and the Festival de Jesús María (1966). but especially with the appearance and massive spread of innovative musical forms, in a process of continental scope that adopted names such as Nueva Canción Latinoamericana and Argentinian Popular Music.[1]

The rise of Cuarteto Zupay was part of a tendency to create vocal groups that characterized Argentinian folk music in the 1960s and 1970s. Los Huanca Hua stood out among the precursors of this movement, appearing in 1960 and inspired by the renovating ideas of Chango Farías Gómez. The "choral folklore" concept existed before, with representatives such as Cuarteto Gómez Carrillo in the 1940s,[note 1] the ensemble Llajta Sumac,[note 2] Los Andariegos, Cuarteto Contemporáneo,[note 3] Conjunto Universitario "Achalay" of La Plata, and Los Trovadores del Norte already in the 1950s. But it was the success achieved by Los Huanca Hua what boosted the formation of vocal groups in Argentina.[2][3]

Until then, most ensembles worked with two voices, and exceptionally with three voices. Vocal ensembles—intimately related to a less visible but far-reaching process of choir development—began to introduce fourth, fifth and sixth voices, counterpoints, and generally explore the musical tools of polyphony and of ancient musical forms designed for singing such as the madrigal, the cantata, the motet, among others.[3]

The innovative possibilities that vocal arrangements presented for traditional folk and popular music led to the creation of several vocal ensembles such as Cuarteto Zupay, Grupo Vocal Argentino, Los Trovadores, Opus Cuatro, Buenos Aires 8, Quinteto Tiempo, Markama, Contracanto, Cantoral, Anacrusa, Santaires, De los Pueblos, Intimayu, etc. Their influence spread to other countries in the region, as was the case of the Chilean group Quilapayún.

Trajectory[edit]

The beginnings[edit]

Cuarteto Zupay was formed in Buenos Aires in 1966 and debuted in May 1967, at the initiative of the brothers Pedro Pablo García Caffi (baritone) and Juan José García Caffi (first tenor), who were joined by Eduardo Vittar Smith (bass) and Aníbal López Monteiro (second tenor).

In the first two albums, the group used the name Cuarteto Vocal Zupay, then simply Cuarteto Zupay after the third one.

The word Zupay or Supay is a Quechua term that corresponds to a demon-god of indigenous origin who was the protagonist of many legends and ancestral dances in the northwestern region of Argentina, historically and culturally linked to the Andean civilization. The Zupay is an ambivalent figure defined by syncretism who has been assimilated to the Devil of Christian culture but that is also worshiped as Lord of the Depths or Salamanca.[4][5] Unlike what happens with the Christian Devil, "the indigenous did not repudiate the Supay but invoked it and worshiped it out of fear, to prevent it from harming them".[6]

Playing with the name, the group would title their tenth album La armonía del Diablo (English: Harmony of the Devil) years later.[7] Furthermore, their seventh album's cover adopted a symbolic image that was used henceforth as isotype of the group, consisting of an inverted black triangle with a smiling devilish face in the center and painted in red, which corresponds to the folkloric description of Zupay.[8] Ultimately, a significant photo of the quartet surrounding a Zupay mask (like the one used in the diabladas of the Oruro Carnival in the Andean altiplano) was included on the cover of the anthology 20 grandes éxitos, released in 2007.[9]

Juan José García Caffi, a classically trained musician and arranger in that first stage, gave the group the style of a chamber music ensemble[note 4][10] inspired by the madrigal renaissance,[11] while Pedro Pablo García Caffi imposed a strict discipline of rehearsals, which earned him the nickname "García Gaddafi",[note 5] but who also established from the beginning a criterion of excellence and professionalism that was unusual at the time.[12][13]

Folklore sin mirar atrás (1967-1969)[edit]

Cuarteto Zupay debuted in May 1967 at La Botica del Ángel, owned by Eduardo Bergara Leumann.

Located in Lima 670, La Botica del Ángel was one of the strongholds in Buenos Aires where artists linked to what was then called "the new Argentinian song" were promoted, which sought to break away from the traditional schemes of the tango-folklore duality, with unclassifiable singer-songwriters such as Nacha Guevara and María Elena Walsh—the latter would be the author with the greatest presence in the historical repertoire of the quartet.[14]

Les Luthiers also debuted that year, with a proposal of unparalleled musical humor. Los Gatos also debuted with La Balsa, giving rise to a genre that adopted the name of rock nacional.

At the time, Argentina was governed by a military dictatorship led by Juan Carlos Onganía that less than a year before had overthrown the radical president Arturo Illia. Shortly after debuting, Los Zupay released a single album that attracted attention, performing a daring version of the Marcha de San Lorenzo a capella. A few years later, the military regime banned another version, psychedelic rock and very humorous and informal, made by the band Billy Bond y La Pesada del Rock and Roll.[15]

In December 1967, the group released their first album Folklore sin mirar atrás (English: Folklore without looking back), with a title that was shared by their second album, released the following year.[7] Both albums, their titles, the back cover texts written by Miguel Smirnoff and the songbook that integrates them, constitute a true cultural manifesto on what they called Argentinian Popular Music which indicated from the beginning a defined artistic-ideological line that would have as a priority the creative freedom and development of new musical forms and poetic contents without abandoning the indigenous, African and Hispanic-colonial roots present in folklore.

In the back cover of the second album, Miguel Smirnoff, then producer of the cycle Canciones para argentinos jóvenes at the Teatro Payró, points out some remarkable details about the music of Los Zupay:

Let us avoid, when talking about this album, the term "folklore", even though it appears in the title of the album, conveniently spiced up. We are talking here about our music, Argentinian and contemporary; it is not "the music of today" either, since Los Zupay continue to evolve permanently and, even within this album, it is easy to notice two or three different stages of the process that is leading them to the creation of "that" which, perhaps, is a faithful expression of our country in the world: the Argentinian Popular Music, thus, with capital letters, integrating the elements of tango and folklore to a rhythmic and melodic base of universal value and easy comprehension anywhere.[16]

Folklore sin mirar atrás Vol. 1 includes the two songs of the first single, Marcha de San Lorenzo and Añoranzas, and others among which stand out Antonino, a Spanish traditional, Zamba del nuevo día, by Armando Tejada Gómez and Oscar Cardozo Ocampo (which would become a classic of the group) and Chacarera de la copla perdida by Lupe García Caffi and Juan José García Caffi. The album also features a rendition of Camino del indio (English: Road of the Indian) by Atahualpa Yupanqui which prompted a sour remark from the author: "Los Zupay, those who asphalted the road of the indian".[7]

In the second half of 1968, the group released its second album, Folklore sin mirar atrás Vol. 2. The album is similar in its thematic structure to the first, but is much more complex and daring, both in the vocal arrangements, the inclusion of dissonances, the participation in four tracks of Oscar López Ruíz's instrumental ensemble, and above all, the use of a drum kit and electric guitar, a radical innovation for folklore.[16] A similar step had been taken three years earlier by North American folk singer Bob Dylan, ending in an uproarious booing at the Newport Folk Festival.[17]

Thematically, the album contains songs of a more varied style, among them Los castillos, by María Elena Walsh, who would become the group's favorite author; Mi pueblo chico by Pérez Pruneda and Adela Cristhensen, also released as a single with great success; Por un viejo muerto, by Damián Sánchez and Bernardo Palombo, a song with social content about a homeless old man freezing to death in the street; and the well-known tango Milonga triste by Sebastián Piana and Homero Manzi.[7]

Several changes (1969-1975)[edit]

In 1969, the first tenor Juan José García Caffi, who was in charge of the vocal arrangements, left the group to devote himself fully to his vocation as composer and conductor of symphony orchestra—in which he excelled.[18] He was replaced by the, then tenor, Eduardo Cogorno, who was performing in the Coro Universitario de Arquitectura, although J.J. García Caffi would again be in charge of the vocal and instrumental arrangements in the 1972, 1973 and 1977 albums[19] The group then consisted of two tenors (L. Monteiro and Cogorno), a baritone (P. P. García Caffi) and a bass (Vittar Smith).

That same year, Los Zupay also began to perform multimedia shows, combining music with projected images (initially slides and films later) and dramatic or poetic texts. The first was Juglares, with vocal arrangements by Mónica Cosachov—pianist and founder of the Camerata Bariloche—and photographs by Juan Carlos Castagnola, accompanied by the group's third album that was released in 1970 with the same title.[20]

Juglares shows a remarkable evolution and marked the consolidation of the quartet's own style where the boundaries between folklore and tango seem blurred within a broader framework dominated by freedom of form and a new sound.[21] The album had tracks that would become fundamental in Cuarteto Zupay's repertoire, such as Si Buenos Aires no fuera así by Eladia Blázquez, Chiquilín de Bachín by Horacio Ferrer and Astor Piazzolla, Jacinto Chiclana (a poem by Jorge Luis Borges set to music by Astor Piazzolla), El violín de Becho by the Uruguayan Alfredo Zitarrosa, Romance del enamorado y la muerte (an anonymous Spanish song from the 15th century), and two protest songs (a genre that had a great development through Latin America at the time), Margarita and the tigres, a humorous chacarera by Mónica Cosachov against the ruling military junta, and Canción de cuna para gobernante, by María Elena Walsh, against the Latin American military dictatorships, which became a classic.

Juglares features prestigious musicians such as Mónica Cosachov, playing piano and harpsichord, Cacho Tirao on guitar, Pedro Pablo Cocchiararo on bassoon and Antonio Yepes on percussion.[21][7] The press of the time emphasized the youth and student attendance regarding the album, as it happened during a massive recital at the Club Atenas of Córdoba, broadcast by the radio of the university:

Over 6,000 young people listened in complete silence to the concert of Cuarteto Zupay... The applause that accompanied the end of the songs touched the hearts of these scholars of Argentinian music and poetry, who had to repeat their performance.[21]

In 1971, they performed at the Teatro Diagonal in Mar del Plata, presenting the multimedia show ¿Queréis saber.... (si un país está bien gobernado y reinan en él buenas costumbres?), about a book written by Pedro Pablo García Caffi, which included texts by Confucius and Argentine authors.[20] Cuarteto Zupay accentuated by then the political and social criticism that the group had already hinted at in Juglares, which would become a central feature of their repertoire and that naturally led them to adhere to the Movimiento del Nuevo Cancionero that Armando Tejada Gómez, Mercedes Sosa and Manuel Matus had started in Mendoza in 1963.[22]

Between 1971 and 1972, the group underwent three changes. As Cogorno went to study singing at the Escuela Superior de Canto de Madrid, López Monteiro and Vittar Smith retired.[19][23] The three were replaced, respectively, by the tenors Gabriel Bobrow and Rubén Verna—coming from Les Luthiers—and the bass Javier Zentner.[note 6] Pedro Pablo García Caffi remained as baritone, already acting as the leader of the group and who would be the only singer to be part of all the quartet's line-ups until its dissolution.[23]

In 1972, a year of great political turmoil due to the decision of the military dictatorship to call for free elections, the popularity that Cuarteto Zupay was gaining among students and young people with transforming ideals was evidenced in a well-remembered recital they performed on May 3, with Piero at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Buenos Aires. The complete recording of the show was never published, but Piero included songs from it in his album Coplas de mi país, where a unique piece of the group's recorded repertoire stands out, La del televisor, in which Los Zupay show their ability to produce complex shows, combining music, humor, theatricality and images. The album also rescued the live performance of Coplas de mi país by Piero, and Los americanos by Alberto Cortez.[24]

That same year, they released their fourth album, Si todos los hombres..., with arrangements by Juan José García Caffi and Javier Zentner.[7] The title was taken from the song by Piero and José Tcherkaski, that concludes the album and features a call to action in its chorus:

Ahora, ahora

que sobran las palabras.

Ahora que gritamos,

ahora que hay más tarde.

—Si todos los hombres... Lyrics by José Tcherkaski.[note 7]

The album includes, among others, El viejo Matías by Víctor Heredia (a song of social content that will become a classic of his repertoire), two songs by María Elena Walsh, Vals municipal (dedicated to Buenos Aires), Aria del salón blanco (parodying the dictatorship), Milonga de andar lejos by Uruguayan Daniel Viglietti (by then one of the most popular Latin American protest singers), and two songs by Atahualpa Yupanqui (Viene clareando and Indiecito dormido).

In March 1973, the elections were held in which Peronism triumphed—after 18 years of proscriptions—ideology to which some of the members of the quartet adhered.[23]

They released their fifth album, Cuarteto Zupay,[7] with songs such as Hoy comamos y bebamos (a Spanish medieval traditional), Mama Angustia (a poem by José Pedroni set to music by Damián Sánchez), Fuego de Animaná by César Isella and Armando Tejada Gómez, and Venceremos (We shall overcome), the famous anthem of the civil rights movement in the United States, in a Spanish version by María Elena Walsh. Also in 1973, they made their first national tour under the slogan Zupay canta MPA (Música Popular Argentina),[note 8] that due to its wide popularity, led the group to do a second national tour the following year.[20] That year, the bass player and arranger Javier Zentner left the group, and Eduardo Vittar Smith returned to until its dissolution.

In 1974, Cuarteto Zupay, the playwright Juan Carlos Gené, and the actor Pepe Soriano teamed up to stage El inglés, a dramatic-musical play written and directed by Juan Carlos Gené and musicalized by Rubén Verna and Oscar Cardozo Ocampo, recreating the First English Invasion of 1806, when a British military government was imposed on Buenos Aires and the subsequent reconquest by a popular army.

One day, Soriano phoned me to tell me that he had talked to the people of Zupay to do a national tour together. Pepe Soriano with Cuarteto Zupay! Well, that situation brought about El inglés. Along with the circumstance of the country, with my problems and my ways of interpreting reality, of course. But the play was cancelled when the military coup of '76 happened, because it was on stage for two years in a row. And then it was reprised in '83. —Juan Carlos Gené.[25]

The play is a central milestone in the group's career, not only because of the success that followed but also because it is one of the finest products of one of Cuarteto Zupay's permanent goals, that of going beyond the limits of purely musical language to develop forms of expression that combine different arts and languages.[26] It is an evident anti-imperialist plea against the military coups d'état happening in Latin America at the time, justified by the National Security doctrine promoted by the United States, opposed by a proposal of national liberation movements founded on popular sovereignty.[27][26] The artists decided to perform the premiere in Córdoba, considering that it is the geographical center of Argentina,[26] and then presented it throughout the country, including seven consecutive months at the Teatro General San Martín in Buenos Aires,[26] with massive success that led them to perform it for free during 1975 in trade unions, neighborhood associations, and schools.[20] The spirit of the play is summarized in the two initial songs, Milonga para mis muertes, sung by Soriano, and Triunfo del pueblo, sung by Los Zupay, which in part of their lyrics say:

Milonga para mis muertes

Y sí, yo he muerto señores, no una vez, cientas morí

pero estoy vivo y contando las cosas que yo viví.

¿Que cómo es ese misterio, que no nací, que morí

cientos y cientos de veces y sigo contando aquí?

Porque mi historia, señores, es la historia del país,

cosas que el suelo ha sufrido, cosas que con él sufrí.

Tierra contra el extranjero, extranjero contra tierra,

la tierra quiere su vida, los de afuera, su dinero.

Yo estuve aquí desde siempre y por siempre estaré aquí,

me matarán muchas veces y al ratito estaré aquí.

Voy a contarles mis muertes, que es contarles que viví

y a mostrarles que yo siempre vivo, viviré y viví.[note 9][28]

Triunfo del pueblo

El triunfo es de los hombres que hacen la tierra,

la muerte es de los vivos que la saquean.

La tierra se quiere justa, injusta quieren que sea

los que desde afuera vienen y la saquean y la saquean.[note 10][28]

In 1975, they received the Premio Prensario for "Best Group of Argentinian Popular Music".[29] That same year, they prepared two shows, Canciones que canta el viento, with anonymous songs from the folkloric songbook and poems by Atahualpa Yupanqui and Jaime Dávalos, and Pequeña Historia de la Canción Popular, based on texts by musicologist María Teresa Melfi, which they presented in schools, popular libraries, unions, and neighborhood clubs in Buenos Aires.[20] In the summer of 1976, Los Zupay, Gené and Soriano staged El inglés again, at the Hermitage Hotel in Mar del Plata.[20]

Dictatorship period (1976-1983)[edit]

In 1976, with the violent military dictatorship self-styled as National Reorganization Process, Cuarteto Zupay stopped presenting new live shows in Argentina until 1980, their last show being Las cosas que pasan, performed that same year at the Teatro Lassalle in Buenos Aires, which included a film of the same name directed by García Caffi and slides by Juan Carlos Castagnola. Cuarteto Zupay was accompanied by Piero, José Luis Castiñeira de Dios on guitar and Rodolfo Mederos on bandoneon.[20]

In July and August 1976, they recorded their sixth album, Canciones que canta el viento,[7] dedicated entirely to perform anonymous traditional songs of Argentinian folklore. The album has been considered one of the best in the history of the group and is the result of a musicological research conducted by María Teresa Melfi. On this occasion the arrangements and musical direction were in charge of Rubén Verna. It includes twelve songs compiled or recorded by Juan Alfonso Carrizo, Manuel Gómez Carrillo, Andrés Chazarreta, Alberto Rodríguez, Isabel Aretz, Carlos Vega, Augusto Cortázar and Leda Valladares. Highlights include the classic carnavalito Viva Jujuy, which opens the album; Vidalita de Ullum, defined on the back cover as "one of the jewels of the Riojan songbook"; the chacarera santiagueña La shalaca; the huaino Ojos negros; A los bosques yo me interno, a hybrid carnavalito-huaino of unknown origin; La Arunguita, a quichua dance of Santiago origin sung in Quechua. The interpretations show the maturity reached by the group to combine tradition and sonorous novelty. Los Zupay were also in charge of playing all the instruments: flute (Pedro P. García Caffi), erkencho and recorder (Marcelo Díaz), guitar, recorder and organ (Rubén Verna), percussion and charango (Eduardo Vittar Smith). Diario 16 de Madrid commented on the result achieved as follows:

Every song performed by Cuarteto Zupay is popular. Only that the Argentinians' popularity is not frozen in time, as it happens in Spain. And so, in eighty minutes of uninterrupted tension, Cuarteto Zupay gives us a lesson on how the most diverse styles can be adapted and mixed without undermining the "purity" of any of them.[11]

For three years they were included in the blacklists of censorship drawn up by the Argentinian dictatorship.[26] For that reason, in 1977 the group left Argentina to perform in Spain, where they recorded and released their seventh album, El arte de Zupay, with a selection of songs included in the first five albums. The arranger was Juan José García Caffi, who had been living in Spain for two years. The album cover included for the first time what would become the isotype of the band: an inverted triangle with Zupay's smiling face in the center.[7]

In Spain, the members of the group became fully aware of the seriousness of the human rights violations committed by the Argentine dictatorship.[13] IAs a result, Marcelo Díaz decided not to return to Argentina with the group the following year. For his part, Rubén Verna left the group—he would return in 1981—to join the vocal quartet Opus Cuatro. Two new tenors joined the group in his place, Horacio Aragona and Gabriel Bobrow—the latter would remain until the dissolution—who joined Pedro P. García Caffi and Eduardo Vittar Smith.[13]

In 1979, after three years without releasing records in Argentina and in order not to lose presence, they released an anthological album titled Retrospectiva, with the participation of Dino Saluzzi, bandoneonist from Salta.

In 1980, the group presented its first show since 1976, La Vuelta de Zupay!, which included the film Postal de guerra (title of a song by María Elena Walsh) made by P. P. García Caffi taking scenes from the Vietnam War.[20] Also in 1980, they presented Cantares de Dos Mundos, performing the anonymous Argentine traditional songs along with Spanish polyphonic plays from the time of the Catholic Monarchs, among them the anonymous chorale that speaks of the Inmaculada Ríu ríu chíu chíu, a chorale by Juan de la Encina, Oy comamos y bebamos, and an unrecorded track, De los álamos vengo.[20]

In 1981, Eduardo Aragona retired and Rubén Verna returned to the group, making the quartet's line-up until its dissolution: Pedro Pablo García Caffi (baritone), Eduardo Vittar Smith (bass), Rubén Verna (tenor) and Gabriel Bobrow (tenor).

After their last change in line-up, Zupay recorded the album Dame la mano y vamos ya in 1981, the first of the three they would dedicate entirely to the work of María Elena Walsh.[7] The album has a double meaning: to pay homage to Los Zupay's favorite author and to be part of the incipient political openness. In the same year, the political parties created the Multipartidaria to pressure the military government, and the trade union and human rights organizations carried out their first massive demonstrations. The title is a phrase of María Elena Walsh included in the song Canción de caminantes and has a clear political meaning.

Siempre nos separaron los que dominan,

pero sabemos que hoy eso se termina.

Dame la mano y vamos ya.

—Canción de caminantes by María Elena Walsh.[note 11]

The album opens with a song composed by Walsh in 1972, Como la cigarra, which would become one of the emblematic songs of the return to democracy in Argentina ("tantas veces me mataron, tantas veces me morí, sin embargo estoy aquí, resucitando"),[note 12] as well as Canción de caminantes. The album includes two songs that already belonged to the group's songbook, such as Vals municipal and above all Serenata para la tierra de uno ("por todo y a pesar de todo/mi amor yo quiero vivir en vos"),[note 13] in the style of a love song, which would also be associated with the historical moment. Requiem de madre is a feminist song, El Señor Juan Sebastián combines the baroque of Bach and the group's own style, while Manuelita la tortuga pays tribute to the powerful influence of María Elena Walsh on several generations of Argentine children. The album ends with the allegorical sadness of Postal de guerra, which had been taken as background track the previous year to make the film for the show La vuelta de Zupay!:

Ay... ¿cuándo volverá

la flor a la rama y el olor al pan?

Lágrimas, lágrimas, lágrimas...

—Postal de guerra, by María Elena Walsh.[note 14]

In late 1981 and early 1982, large mass demonstrations were held against the military dictatorship and then the Falklands War, which ended with the Argentine defeat and the collapse of the regime, forced to call elections for the end of 1983 and without the power to establish conditions.

In that framework, Cuarteto Zupay released its tenth album, La armonía del Diablo (English: The harmony of the Devil).[7] The title of the album, in which the word "Diablo" is used for self-reference,[note 15] has a variety of meanings. The most obvious alludes, almost literally, to the music of Los Zupay. But the expression "harmony of the Devil" also refers to the tritone or augmented fourth interval, a dissonant harmony of three whole tones, forbidden in the Middle Ages by the Catholic Church for attributing it to the Devil.[30] Finally, the group suggests a third meaning by saying on the back cover that "harmony", figuratively, means "friendship and good correspondence".[7]

The album includes twelve songs, each of which is performed with a guest artist.[note 16] It opens with Zamba del nuevo día, one of the emblematic songs of the cancionero Zupay, already included in the first album, which this time has the author of the music Oscar Cardozo Ocampo, playing guitar and piano. Then comes El sueño grande ("somos Latinoamérica, no lo olvidemos nunca más"),[note 17] by Sergio Denis. The third track of side A is Vidala del nombrador, by Falú and Dávalos, with the recitation of the salteño poet Jaime Dávalos. Track four is Fuego de Animaná ("ayer nomás salió el pueblo")[note 18] by Isella and T. Gómez, with the recitation of Armando Tejada Gómez, followed by another one of their hits El viejo Matías, with the voice of its author Víctor Heredia, in his return to the country anticipating the joint recitals that they would perform that year and in 1984. Side A closes with Riu riu chi, an anonymous Spanish piece from the 16th century, which they perform together with the medievalist ensemble Danserye.

Side B of La armonía del Diablo opens with the tango Chiquilín de Bachín by Astor Piazzolla and Ferrer, with Leopoldo Federico on bandoneon. Then follows Canción de cuna para un gobernante ("que ya te están velando los estudiantes")[note 19] by María Elena Walsh, with the instrumental group Gente de Buenos Aires (Horacio Malvicino, Daniel Binelli, Adalberto Cevasco and Enrique Roizner). Track four is La baguala which they sing with Chango Farías Gómez, historical inspirer of South American vocal groups.[2] Track five is La añera by A. Yupanqui, with Manolo Juárez on piano. The album ends with Triunfo del pueblo, one of the most vibrant themes of El inglés, sang with the actor Pepe Soriano.[7]

Armonía del Diablo was also presented that year as a musical-choreographic show with dancer Teresa Duggan and choreography by Ana Itelman.[20]

Still in 1982, the Organization of American States released an album completely dedicated to Cuarteto Zupay, as part of its collection Ediciones Interamericanas de Música, with a painting by Raúl Russo on the cover and based on songs included in the previous albums.[7] Finally, they performed with Víctor Heredia at the Estadio Obras Sanitarias, in a historical and highly emotional concert because it marked the return to the stage of the former, after his exile.[31][32] Víctor Heredia, who suffered the disappearance of his sister María Cristina, a union activist, became one of the authors who best expressed the tragedy of the dictatorship.[33] Two years later, Cuarteto Zupay would include Heredia's song Informe de la situación within the album Memoria del pueblo.

Also during that year, a new version of the album Canciones que canta el viento was released.

In January 1983, Zupay along with Juan Carlos Gené and Pepe Soriano, revived El inglés, the play they had to cancel when the military dictatorship took power seven years before. The revival was performed at the Teatro Regina in Buenos Aires and then it was performed all over the country in a national tour, presented even at the Cosquín Festival.[34] The success and the audience it attracted, as well as the return to Argentine theater of Juan Carlos Gené, one of the most important playwrights in Latin America—then exiled in Venezuela—turned the staging of the play into one of the most representative cultural events of the post Malvinas War and the retreat of the dictatorship.[27][26]

The play received the 1983 Premio Prensario and was recorded on disc by Philips, with the participation of the following musicians: Mauricio Cardozo Ocampo on Spanish guitar and twelve-string guitar; Babu Cerviño on synthesizer; Carmelo Saíta on bells and metal hoops; Edgardo Rudnitzky on tam tam and timpani; José Luis Colzani on drums; Felipe Oscar Pérez on piano; Oscar Alem on bass; Telmo Gómez and Horacio Viola on trumpets; Carlos Hugo Borgnia and Norberto Claudio Tavella on trombones.

El inglés has been defined as:

A fundamental piece of the Argentinian theater of all times. Acting and music unraveling the mysteries of our history in Juan Carlos Gené's epic play par excellence.[35]

Recalling that moment, Pepe Soriano said:

The play's success even took us to the Cosquín Festival and it was the only play that was presented at a folk music festival. That evening is unforgettable to me, with the audience standing with white handkerchiefs and the church bells ringing. To my friends the Zupay, I can only say: thank you! —Pepe Soriano.[34]

They released two more albums that same year, a compilation in Brazil and a reunion album with Litto Nebbia, founder of Argentine rock. The latter is titled Nebbia-Zupay, para que se encuentran los hombres and contains eleven songs that they performed together in different shows. Of the songs, eight are by Nebbia (Nueva zamba para mi tierra, Yo no permito, etc.), two are by María Elena Walsh (Serenata para la tierra de uno and Barco quieto), ending the album with Ave María by Schubert. Among the musicians participating in this album are Oscar Moro, drummer of Los Gatos, in Nueva zamba para mi tierra, Lalo de los Santos on bass, guitar and backing vocals, drummer Norberto Minichillo, and Uruguayan percussionist Cacho Tejera in Ojos que ven, corazón que siente. On the back cover of the album, Litto Nebbia says that "it took us a week to record it and 20 years of professional career to be able to do it."[7]

Democracy period (1984-1991)[edit]

On December 10, 1983, the new democratic authorities took office. The first years were marked by the revelations of the atrocities committed by the dictatorship, the trials to the military and the resistances and attempts of coups d'état to avoid investigations and convictions.

Within this historical framework, Cuarteto Zupay released their 15th album in 1984, Memoria del pueblo, which would turn out to be the most successful in the group's history.[7][29]

The album features on the cover a popular demonstration (photo by Juan Carlos Castagnola) and quotes as a main slogan a phrase by Joan Manuel Serrat, who was also part of the dictatorship's blacklist:

"Memory is essential in order not to repeat mistakes...; if one does not remember exactly what happened, it is very difficult for one to appreciate what one has."[7]

Memoria del pueblo opens with Oración a la Justicia ("señora de ojos vendados... quítate la venda y mira, cuánta mentira")[note 20] by María Elena Walsh, in a powerful cover that became one of the band's classics. Immediately afterwards comes Solo le pido a Dios by León Gieco, a song written in 1978 that was a symbol of the popular cultural mobilization of young people during the Malvinas War. The third track is Señora violencia by Miguel Cantilo and Piero, a condemnation of violence beyond the ends pursued, a theme that is repeated in Cuentos de la jungla, the last track of side A, also by Cantilo. The other two tracks on side A are Milonga del muerto ("no conviene que se conviene que se sepa que muere gente en la guerra"),[note 21] an anti-war poem by Jorge Luis Borges, with music by Sebastián Piana; and two songs by Charly García, Inconsciente colectivo-Los dinosaurios ("los amigos del barrio pueden desaparecer, pero los dinosaurios van a desaparecer"),[note 22] this last song emblematic of the disappearance of people crimes that characterized the Argentinian dictatorship.

Side B opens with Informe de la situación ("duele a mi persona tener que expresar/que aquí no ha quedado casi nada en pie")[note 23] by Víctor Heredia, a song defined as "chronicle of the tragedy of a generation and a country",[36] followed by M. E Walsh's Balada del Comudus Viscach, a parody of the average man without ideals. Track three is Aquí hay las madres..., an unusual song of García Caffi and Verna dedicated to the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, followed by Levántate y canta by Isella and H. Negro. The last two tracks of the album are Coplas de mi país by Piero and José Tcherkaski and Nueva zamba para mi tierra by Litto Nebbia, in a more accelerated and energetic version than the one they performed the previous year in Nebbia-Zupay....

Following the artistic line on Argentinian Popular Music, pointed out since the beginnings of the group, the album includes songs coming from traditional folk music, tango and national rock, without altering the stylistic continuity of the interpretations. Among the musicians accompanying Cuarteto Zupay on the album are Litto Nebbia, Lalo de los Santos (bass), Norberto Minichilo (drums), Manolo Yanes and Babu Cerviño (synthesizer), Mauricio Cardozo Ocampo (Spanish guitar), etc.[7]

During that year and the following year, they performed the show Memoria del pueblo throughout the country, with the songs from the album and a film of the same name directed by Pedro Pablo García Caffi, which includes testimonies by Nobel Peace Prize Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, the president of Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo Hebe de Bonafini, former Malvinas combatants, Piero, Víctor Heredia, Miguel Cantilo, César Isella, and Jorge Luis Borges, among others.[20]

In April 1984, Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés visited Argentina for the first time to present a historic performance at the Obras Sanitarias Stadium, together with Cuarteto Zupay, León Gieco, Víctor Heredia, Piero, César Isella and Antonio Tarragó Ros, who were invited to share the stage. The event has been considered as "the greatest sonorous manifestation of the return to democracy".[37] These were two Cuban musicians, founders of the Cuban nueva trova, rigorously banned in Argentina throughout the dictatorship, whose songs had circulated among young people from hand to hand, in clandestine recordings.[37] Two performances were scheduled initially, but the massive attendance led to fifteen.[38]

Cuarteto Zupay performed three songs in those memorable concerts: Para el pueblo lo que es del pueblo, together with Silvio Rodríguez and Piero, Ojalá, together with Silvio in an anthology version that became one of the main songs of their songbook, and Canción con todos, together with the rest of the artists, in another anthology version. The concerts were recorded in a double album released that same year under the title Silvio Rodríguez - Pablo Milanés en vivo en Argentina.

On May 5 and 6, 1984, Los Zupay, César Isella and Víctor Heredia came together to perform two joint recitals at the Estadio Luna Park. The show was called Canto a la poesía, where each one contributed songs from their repertoire with lyrics by their favorite poets: María Elena Walsh for Cuarteto Zupay, Pablo Neruda for Víctor Heredia and José Pedroni for César Isella. The recitals were a success and the live recording of them was released that same year, in a double album with the same title, Canto a la poesía, selling 300,000 units.[39][7]

The album gathers 25 poems, 10 by Pablo Neruda, 9 by M. E. Walsh and 6 by José Pedroni. It opens and closes with two songs by M. E. Walsh sung by everyone, Canción de caminantes and La cigarra. The songs of the three poets alternate, with the artists sometimes singing them alone and sometimes together. The rest of the M. E. Walsh songs included are Serenata para la tierra de uno, Requiem de madre, Sábana y mantel, Vals municipal, El señor Juan Sebastián, Manuelita la tortuga and Balada del Comudus Vizcach. The songs about Neruda's poems are Sube conmigo amor americano, La muerte del mundo cae sobre mi vida, Niña morena y ágil, El pueblo victorioso, Porque ha salido el sol, Viejo ciego, Levántate conmigo and Cuerpo de mujer, all set to music by V. Heredia, to which were added La patria dividida and Soneto 93, with music by C. Isella. Finally, the songs with poems by Pedroni are Cuando estoy triste, La cuna de tu hijo, Mama Angustia, Un día, un dulce día, Palabra de mi esperanza and Madre luz; the first three with music by Damián Sánchez and the last three by César Isella.

Among the highlights of the recital were Sube conmigo amor americano, Porque ha salido el sol, La patria dividida—bursting into applause when they sang "quiero la luz de Chile enarbolada" (English: I want the light of Chile to be hoisted)—and La cigarra—with the audience celebrating every time the artists said "y volví cantando" (English: and I came back singing)—sung by all of them together.[7]

In 1984, they were also invited to be part of the album Jaime Torres y su gente, by the outstanding charanguista Jaime Torres, singing in Mambo machaguay, as well as performing as instrumentalists.

In 1985, appeared Canciones de amor, their 17th album, where the versions of Te quiero ("si te quiero es porque sos/mi amor, mi cómplice y todo/y en la calle codo a codo/somos mucho más que dos")[note 24] by Alberto Favero and the Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti, which would become a popular hit; Ojalá by Silvio Rodríguez and Sinceramente tuyo by Joan Manuel Serrat. The album also includes romantic songs from Argentine folk music (Tonada del viejo amor, by Falú and Dávalos), from tango (Cuando tú no estás by Gardel and Le Pera) and from rock nacional (Cuando yo me transforme by Nebbia and Ingaramo).

In this album, Los Zupay decidedly incorporated the Latin American songbook, adding a song by Silvio Rodríguez song, two songs by Pablo Milanés (Para vivir and Como si fuera primavera with lyrics by Nicolás Guillén) and one by Violeta Parra (Que he sacado con quererte). Finally, Mis ganas by Jairo and María Elena Walsh and Álamos de primavera (no me dejes morir donde no debo) by Víctor Heredia are included. The album also features the group AfroCuba as guest musicians.[7]

Also in 1985, Cuarteto Zupay was invited by Mercedes Sosa to participate in her album Vengo a ofrecer mi corazón, singing Venas abiertas by Mario Schajris and Leo Sujatovich. For their long trajectory until 1985, the Konex Foundation awarded them with an Honorary Degree as one of the best folklore groups in the history of Argentina.

In 1986, they released two albums dedicated to María Elena Walsh, Canciones para convivir and Canciones infantiles, the first of songs for adults and the second of songs for children. Canciones para convivir includes ¿Diablo estás?, Palomas de la ciudad, Las aguas vivas, El buen modo, Para los demás, El viejo varieté, Sapo Fierro, Sin señal de adiós, Orquesta de señoritas and La clara fuente. To the previous 10 songs they added two previous hits: Oración a la justicia and Balada del Comudus Viscach.[7]

Canciones infantiles related Los Zupay to the world of Argentine children in which M. E. Walsh had reigned for five generations.[40] This is an unusual album in Argentinian popular music,[note 25] by a group of established artists making an album entirely dedicated to children. Reflecting on art for children, Walsh has said:

Among the literati, the activity of writing "for children" is often considered in a somewhat derogatory manner. Among other things, children do not manufacture literary prestige: they do not write chronicles in newspapers, award prizes or offer scholarships.[40]

The album includes María Elena Walsh's most famous children's songs, such as Canción de la vacuna, El último tranvía, La reina batata, La pájara pinta, El reino del revés, Canción del jardinero, La vaca estuda and Canción de tomar el té. It also includes Los castillos, which had already been part of the third album, Juglares (1970). It is noticeable that the album does not include M. E. Walsh's most famous children's song, Manuelita, la tortuga, which was already part of the group's repertoire as well as part of the album Dame la mano y vamos ya, from 1981, the first one they dedicated to the author.[7] Between 1988 and 1990, the group performed the show Canciones infantiles throughout the country, including videos of each song in which the members sing in dreamlike and fantastic environments.[41][20]

In May 1987, Cuarteto Zupay turned 20 years old. To honor that, they released an album titled May '67, playing in a way with the meaning of May '68, the workers and students rebellions that took place in France on that date. It is a retrospective in which the group selected songs from different periods and albums. That year they performed at the Cosquín Festival where a Plaque of Honor was placed, in recognition of the two decades of the group's career, and then they celebrated the anniversary with a concert at the Luna Park.[29][20]

In 1989, they released their last album, Con los pies en la tierra, performed with the Banco Provincia Choir conducted by Fernando Terán.[7] The album coincided with a historical moment in which the world was changing drastically, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, prelude to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, as well as the beginning of globalization. Simultaneously, Argentina was living a moment of chaos and confusion, with constant military insurrections that had achieved the sanction of the Argentinian impunity laws and a crisis characterized by hyperinflation and an unprecedented increase in poverty, which forced President Alfonsín to resign and hand over power early to his successor, Carlos Menem.

The title of the album is taken from a song by Julio Lacarra which has as its central message the phrase "con los pies en la tierra y un sueño cierto" (English: with feet on the ground and a true dream). The tracks express concern and questions about the fate of the world and humanity. The concern for the world, a theme absent in the previous repertoire of Cuarteto Zupay, is present in Padre ("Padre, que están matando la tierra, deja ya de llorar, que nos han declarado la guerra")[note 26] by Joan Manuel Serrat; in Patria es humanidad, a flamenco style song based on a phrase by José Martí, by Alberto Favero and Mario Benedetti; in Fragilidad ("acero y piel, combinación tan cruel")[note 27] by Sting, a song against violence; and in Ciegas banderas ("ya no quiero más banderas en mi mundo/que se enfrenten como gallos en la arena")[note 28] by Víctor Heredia.

The album also includes several songs reflecting on the human condition such as Levántate y canta ("¿Por qué caerse y entregar las alas?/¿Por qué rendirse y manotear las ruinas?")[note 29] by Isella and Héctor Negro, A redoblar, by Mauricio Ubal and Rubén Olivera, emblematic song of the resistance to the Uruguayan dictatorship by the group Rumbo,[42] Balada del ventarrón by Chico Novarro and María Elena Walsh, about the permanently renewed challenges that life presents, Piedra y camino ("soy peregrino de un sueño lejano y bello")[note 30] by Atahualpa Yupanqui, and a song by Rubén Verna and journalist Carlos Abrevaya, titled Todo está por hacerse todavía ("porque allí donde sea el fin será el principio").[note 31] The album ends with a song by María Elena Walsh, El viejo varieté, which says in its final verse:

¡A escena los artistas, mientras el mundo exista no se suspende la función![note 32]

During 1989 and 1990, Los Zupay presented the show Con los pies en la tierra, together with the Banco Provincia Choir, at the General San Martín and Alvear theaters in Buenos Aires, and the rest of the country. In 1991, they launched a new show, Y ahora.... qué hacemos?, based on a book and with the participation of the journalist and humorist Carlos Abrevaya, at the Teatro General San Martín in Buenos Aires. Abrevaya had stood out for his joint work with Jorge Guinzburg in the comic strip Diógenes y el Linyera and the magazine Humor®, and later in the television program La noticia rebelde, which revolutionized criticism and television language from the first year of the democratic era.[20]

In October 1991, Cuarteto Zupay disbanded.[43] The main reason was that, with the takeover of Peronism in 1989, Pedro Pablo García Caffi started to give priority to his desire to devote himself to classical music conducting. In 1990, he produced an album for the Buenos Aires Philharmonic at the Teatro Colón and, at the beginning of 1991, he presented to the then mayor of the Municipality of Buenos Aires, Carlos Grosso, a project to restructure the Philharmonic, which would finally materialize with his appointment as General Director in 1992.[44]

The final line-up of Cuarteto Zupay was Pedro Pablo García Caffi, Eduardo Vittar Smith, Rubén Verna and Gabriel Bobrow.[43]

Discography[edit]

Albums[edit]

- Folklore sin mirar atrás, Trova, TL 13, 1967

- Folklore sin mirar atrás Vol. 2, Trova, TL 18, 1968

- Juglares, CBS, 19.007, 1970

- Si todos los hombres..., CBS, 19.141, 1972

- Cuarteto Zupay, CBS 19316, 1973

- Canciones que canta el viento, Philips, 5334, 1976

- Dame la mano y vamos ya, Philips, 5377, 1981

- La armonía del Diablo, Philips, LP 5413, 1982

- El inglés (ft. Pepe Soriano), Philips, 22006/07, 1983

- Nebbia-Zupay, para que se encuentren los hombres (ft. Litto Nebbia), RCA TLP 50134, 1983

- Memoria del pueblo, Philips, 822 690 - 1, 1984

- Canto a la poesía, Philips, 822 328/9 - 1, 1984

- Canciones de amor, Philips, 824 979 -1, 1985

- Canciones para convivir, Philips, 830 235 - 1, 1986

- Canciones infantiles, Philips, 830 664 - 1, 1986

- Con los pies en la tierra, Philips, 842 118 - 1, 1989

Simple records[edit]

- La marcha de San Lorenzo & Añoranzas, Trova TS 33-727, 1967

- Mi pueblo chico & Chacarera de la copla perdida, Trova TS 33-732, 1967

Compilations[edit]

- Cuarteto Zupay: Retrospectiva, Philips, 5266, 1979

- Cuarteto Zupay - Argentina, Organization of American States, OEA-019, 1982

- Cuarteto Zupay - Antología, Philips, 6347 403 Série Azul (Brazil), 1983

- Mayo del 67, Philips 67416, 1987

Notes[edit]

- ^ Cuarteto Gómez Carrillo was formed in Santiago del Estero in the early 1940s, and consisted of four siblings: Cármen Gómez Carrillo ("Chocha"), Manuel Gómez Carrillo ("Manolo"), Julio Gómez Carrillo ("Chololo") and Jorge Rubén Gómez Carrillo ("Gougi").

- ^ Llajta Sumac was directed by Esteban Velárdez and included Remberto Narváez, Guillermo Arbos, Lorenzo Vergara and Miguel Ángel Trejo on piano.

- ^ Cuarteto Contemporáneo was formed in Mendoza in the 1950s and had Tito Francia, Jorge Montana, Mario Bravo and Oscar Cánova.

- ^ The first distinction the group received was the Honorary Diploma awarded by the Asociación Argentina de Música de Cámara in 1967.

- ^ Muammar Gaddafi is a revolutionary leader of Libya, who has been described as a dictator by his critics.

- ^ The latter would assume the role of instrumental and vocal arranger in addition to acting as bass.

- ^ English: Now, now/when words are unnecessary./Now that we shout,/now that there is more later.

- ^ English: Zupay sings MPA (Argentinian Popular Music)

- ^ English: And yes, I have died gentlemen, not once, hundreds of times I died/but I'm alive and telling the things that I lived./So how is that a mystery, that I wasn't born, that I died/hundreds and hundreds of times and I'm still telling it here?/Because my story, gentlemen, is the story of the country,/things that the land has suffered, things that I suffered with it./Land against foreigner, foreigner against land,/the land wants its life, the outsiders, its money./I was here since always and I will always be here,/they will kill me many times and soon I will be back here./I will tell about my deaths, which is to tell that I lived/and to show that I always live, I will live, and I lived.

- ^ English: Triumph is for the men who make the land,/death belongs to the ones who plunder it./The land is wanted just, unjust they want it to be/those who come from outside to plunder it and plunder it.

- ^ English: Those in power always separated us,/but we know that will end today./Give me your hand and let's go.

- ^ English: So many times they killed me, so many times I died, yet here I am, resurrecting.

- ^ English: For everything and in spite of everything my love I want to live in you.

- ^ English: Ah... when shall return/the flower to the branch and the smell to the bread?/Tears, tears, tears...

- ^ The back cover of the album La armonía del Diablo includes a box explaining the title, defining the two nouns in the title. "Armonía ("Harmony"): union or combination of pleasant sounds; art of forming musical chords; proportion and correspondence of the parts of a whole; in a figurative sense, friendship and good correspondence. Zupay: voice of Quechua root, origin of infinity of legends in the Northwest of our land; in Spanish language: Diablo"

- ^ With the exception of Vidala para mi sombra

- ^ English: We are Latin America, let us never forget it again.

- ^ English: Just yesterday the people came out.

- ^ English: That the students are already watching over you.

- ^ English: Blindfolded lady... take off your blindfold and see, so many lies.

- ^ English: It is not convenient for the public to know that people are dying in the war.

- ^ English: The neighborhood friends may disappear, but the dinosaurs will disappear.

- ^ English: It pains me personally to have to express/that almost nothing remains standing here.

- ^ English: If I love you it is because you are/my love, my accomplice and everything/and in the street side by side/we are much more than two.

- ^ Hernán Figueroa Reyes is one of the exceptions, having recorded Para los más jóvenes un regalo de...

- ^ English: Father, they are killing the earth, stop crying already, because they have declared war on us.

- ^ English: steel and skin, such a cruel combination.

- ^ English: I don't want any more flags in my world/to face each other like roosters in the sand.

- ^ English: Why fall down and surrender the wings?/Why give up and slap the ruins?

- ^ English: I am a pilgrim of a distant and beautiful dream.

- ^ English: because wherever the end is will be the beginning.

- ^ English: Artists to the stage, as long as the world exists, the show won't be cancelled!

References[edit]

- ^ Brune, Krista (3 May 2004). "MPB in a Comparative Latin American Context: Music as Social and Political Engagement in the 1960s and 1970s". Vanderbilt University.[dead link]

- ^ a b Frías, Miguel (3 May 2004). "Entrevista con Chango Farías Gómez. El tótem del folclore". Clarín.

- ^ a b Haimovich, Laura (24 January 2001). "Los Farías Gómez, a 40 años de los Huanca Hua. Asuntos de familia".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Cornejo, M. (3 January 2008). "El Sicu Moreno en la Diablada de Puno". Puno Portal. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ "El zupay". Folklore del Norte.

- ^ Cuentas Ormachea, Enrique (1986). La Diablada: una expresión de coreografía mestiza del altiplano del Collao. Lima. p. 35.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Cuarteto Zupay. Discografía". Philips. 1982. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- ^ "El arte de Zupay". Spain: Universal. 1977. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009.

- ^ "20 grandes éxitos". Argentina: Universal. 2007.

- ^ "Distinciones". Sitio oficial de Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008.

- ^ a b Diario 16. Madrid, Spain, cited on "Prensa". Sitio oficial de Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008.

Los Zupay dominan la técnica del madrigal, los tonos mágicos del folklore e incluso los ribetes de la canción meliflua,...

- ^ Abiuso, Marina (14 February 2009). "Pedro Pablo García Caffi: 'Disfruto de un concierto en el Colón igual que de un partido en la Bombonera'". Diario Perfil.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Padilla, Vicente (2006). "Aragona, ex-integrante del Cuarteto Zupay. Un juglar entre nosotros". Bariloche: La Puerta.[dead link]

- ^ Schóó, Ernesto (18 June 1968). "La nueva canción argentina". London: Revista Primera Plana, republicada por Mágicas Ruinas. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009.

- ^ Schóó, Ernesto (2005). "Mi nombre es Bond, Billy Bond". Cinebraille.

- ^ a b Miguel SMIRNOFF (1968): "Back cover commentary", on Folklore sin mirar atrás Vol. 2, Buenos Aires: Trova, 1968.

- ^ Marqusee, Mike (2 August 2002). "Come you masters of war. When Dylan played Newport in 1965 he shocked the crowd". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "José María Caffi: currículum". Orquesta Filarmónica de Mendoza. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009.

- ^ a b "Biografía". Sitio Oficial de Eduardo Cogorno.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Cuarteto Zupay. Espectáculos". Sitio Oficial de Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009.

- ^ a b c "Juglares". Sitio Oficial de Eduardo Cogorno.

- ^ Díaz, Claudio F. (2004). "Una vanguardia en el folklore argentino: canciones populares, intelectuales y política en la emergencia del 'Nuevo Cancionero'". Mar del Plata: 2º Congreso Nacional CELEHIS de Literatura.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Rivas, Ana Clara (1983). Los Zupay. Buenos Aires: El Juglar.

- ^ "Coplas de mi país". Buenos Aires: CBS. 1972.

- ^ Reportaje a Juan Carlos Gené. Vol. May 2006. 2006. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f "El inglés y las razones del éxito claro y genuino". Buenos Aires: Platea. 27 January 1983. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ a b Pogoriles, Eduardo (12 January 1983). "La obra de Gené se repuso, con Soriano y Zupay. Humor e ingenio hacen que "El inglés" siga creciendo". Buenos Aires: La Voz. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ a b Cuarteto Zupay and Pepe Soriano (1983). El Inglés, Philips, 22006/7.

- ^ a b c "Cuarteto Zupay. Distinciones". Sitio Oficial de Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008.

- ^ Smith, F. J. (1979). Some aspects of the tritone and the semitritone in the Speculum Musicae: the non-emergence of the diabolus in music. Vol. 1979. pp. 63–74.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Biografía de Víctor Heredia". Sitio oficial de Víctor Heredia.

- ^ "Víctor Heredia". CMTV El Canal de la Música.

- ^ Frías, Miguel (24 November 2003). "Entrevista con Víctor Heredia: 'No tengo contradicciones, sé quién soy'". Clarín.

- ^ a b Soriano, Pepe. "El inglés". Sitio oficial de Pepe Soriano. Archived from the original on 2022-01-27. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "El teatro municipal Colón y su programación de diciembre". Mar del Plata: Punto Noticias.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Biografía de Víctor Heredia". Sitio oficial de Víctor Heredia. 17 May 1997.

Sus canciones se han vuelto no solo las crónicas de una generación, sino también las de un país, como lo retrata el clásico Informe de la situación.

- ^ a b Vitale, Cristian (9 July 2008). "Silvio Rodríguez y Pablo Milanés, reeditados. Aquella canción con todos". Pagina/12.

- ^ EGC (23 April 2007). El compromiso, el amor y el tiempo según Pablo.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "César Isella". Debiografías. 30 April 2009. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009.

En 1984 realiza junto a Víctor Heredia y el Cuarteto Zupay el espectáculo 'Canto a la poesía', integrado por poemas musicalizados de Pablo Neruda, María Elena Walsh y José Pedroni, presentado con un éxito resonante en el Luna Park, recital que luego fuera difundido en un álbum que vendió 300.000 ejemplares.

- ^ a b Garralón, Ana (2004). "María Elena Walsh, o El discreto encanto de la tenacidad". Alicante, Spain. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "El reino del revés (f. E. Walsh)" (Video). YouTube. 1987.[dead link]

- ^ "Mauricio Ubal: 'En Rumbo entendíamos que una buena canción era el mejor instrumento político que podíamos dar en ese momento'" (Video). Montevideo: El Espectador. 8 December 2000.

- ^ a b Vargas Vera, René (17 May 1997). "Vuelven las voces de Zupay. Berna y Vittar Smith interpretan 'Clásicos populares'". La Nación.

- ^ "Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Antecedentes e historial profesional". Sitio oficial de Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009.

Bibliography[edit]

- Rivas, Ana Clara (1983). Los Zupay. Buenos Aires: El Juglar.

External links[edit]

- "Cuarteto Zupay". Sitio oficial de Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009.

- "Discografía del Cuarteto Zupay". Sitio oficial de Pedro Pablo García Caffi. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- Fundación Konex. "Cuarteto Zupay". Sitio oficial de los Premios Konex. Archived from the original on 18 July 2003.

- "Zupay canciones (alfabético)". Gabriel Bobrow. Retrieved 2022-12-14.