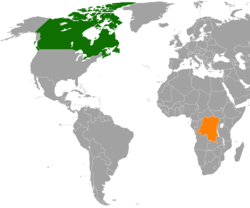

Canada–Democratic Republic of the Congo relations

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article needs to be updated. (February 2023) |

| |

Canada | DR Congo |

|---|---|

Canada–Democratic Republic of the Congo relations are the bilateral relations between Canada and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Canada has an embassy in Kinshasa and D.R. Congo has an embassy in Ottawa.

While the Canadian government provided in 2009 US$40 million in development aid to the DRC,[1] Canadian companies held US$4.5 billion in mining-related investments there,[2] making the DRC the first or second-largest African destination for Canadian mining activities at the end of the 2000s.[3][4] The Government of Canada has reported 28 Canadian mining and exploration companies operating in the D.R. Congo between 2001 and 2009, of which four (Anvil Mining, First Quantum Minerals, Katanga Mining, Lundin Mining) were engaged in commercial-scale extraction, with their collective assets in the DRC ranging from Cdn.$161 mill. in 2003 up to $5.2 bill. in 2008,[3] and these companies were supported in 2009 by Canadian and Quebec public pension plan investments of Cdn.$319 mill.[5] Natural Resources Canada valued Canadian mining assets in the DRC at Cdn.$2.6 bn. in 2011.[6]

In 2010, Canada's temporary delay and abstention from a World Bank decision to cancel most of the D.R. Congo's external debt and complete the review of the DRC's Extended Credit Facility,[7] was officially based on Canadian concerns over reform sustainability adversely affecting DRC's investment climate and development objectives.[8] While Canada's actions drew criticism from the Congolese government, diplomatic relations were not deemed to have been impaired.[9] Canada also expressed concerns over the DRC's relations with Canadian companies,[10] and the abstention was reportedly linked directly to First Quantum's legal proceedings.[11]

In addition to a total of 2,200 Canadian military personnel deployed to Congolese and Zairean conflicts during 1960–1964 and 1996, individual Canadians have had significant roles in the history of the Congo, including:

- Leading the military conquest of the Katanga region for Belgium's King Leopold II in 1891: William Grant Stairs.[12]

- Printing, from 1903 to 1908, the very first books to be published in the Lingala language, a language which became a lingua franca of the D.R. Congo, with 25 million speakers worldwide: Mère Marie-Bernadette.[13][14][15]

- Leading diplomatic and military missions of the United Nations to Zaire and the D.R. Congo during the 1990s and 2000s: Raymond Chrétien, 1996;[16] Maurice Baril, 1996[17] and 2003;[18] Philip Lancaster, 2008–2009[19] and 2010.[20]

- Political counsel to President Laurent Kabila during 1997–1998: former Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark.[21][22]

- Plotting, unsuccessfully, an overthrow of Laurent Kabila's government in 1998: Robert Stewart.[23][24]

- Management and partial privatization of the D.R. Congo's national mining company, Gécamines, 2005–2009: Paul Fortin.[25][26]

- Legal representation for former military leader Laurent Nkunda against allegations of war crimes at a military tribunal in Rwanda, 2009–2010: Stéphane Bourgon.[27]

History[edit]

Victorian era[edit]

In 1887, William Henry Faulknor, a young Canadian from Hamilton, Ontario[28] who had joined the Plymouth Brethren evangelical movement, arrived at Bunkeya, in Katanga, a centralized state ruled by Msiri; Msiri employed Faulknor and other missionaries as "errand boys", symbols of his influence, while Faulknor taught and converted a small group of redeemed slaves.[29]

William Grant Stairs (1863–1892), a Canadian born in Halifax, Nova Scotia and educated at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario, was a civil engineer, explorer and mercenary who was appointed by Belgium's King Leopold II to lead an expedition in 1891 of four hundred men which captured the Katanga (Shaba) copper territories for Belgium.[30] Contemporaneous accounts of the expedition reported that during a confrontation, Katanga's king Msiri was shot dead and then decapitated, the head placed on a stake by Stairs's forces.[31][32] Stairs then began reorganising affairs, appointing Msiri's son Mukandavantu (Mukanda Bantu) to replace Msiri, and securing the Congo State's authority over a fifty-mile radius.[33] Stairs himself died of malaria only six months later while on trek to the coast, in Chinde, Mozambique, and was buried there.[32] The Brethren missionaries including Faulknor made no attempt to obstruct Stairs's campaign and relied on the Belgian military following Msiri's defeat.[29] Faulknor left Katanga in 1892, and returned to Canada.[12] The Canadian Baptist Mission (Mission des Baptistes Réguliers du Canada) established a presence in the Congo in 1926,[34] and had two missions in southern Léopoldville Province in 1946.[35]

Possibly the earliest Canadian woman to live and work in the Congo was a Catholic missionary and book printer from Quebec: Mère Marie-Bernadette (née Bernadette Beaupré) was born in 1877 in Saint-Raymond, entered the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary in 1894, and died in Boma, Congo Free State in 1908,[36][37] from trypanosomiasis.[13][38] On her departure for the Congo, Soeur Marie-Bernadette was destined for an orphanage to be founded at the mission station of Stanley-Falls,[39] however she was posted downriver at Nouvelle-Anvers instead, arriving there on 27 July 1900.[40] Having received training in typesetting while at the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary institute in Vanves, France, [41] Marie-Bernadette was designated in 1901[13] by Égide De Boeck (1875–1944), the Scheut missionary and vice-director of the colonial boarding school at Nouvelle-Anvers,[42][43] to undertake the printing and binding[41] of the very first books to be published in the Lingala language; these grammars, lexicons, religious tracts and hymn books were authored by De Boeck,[15] and by Father Camille Van Ronslé.[14] With a very limited supply of type, only one page could be printed at a time,[13] however at least eight volumes in Lingala were published under Marie-Bernadette's guidance, beginning in 1903 with Mambi makristu [Things Christian] by Van Ronslé and Buku moke moa kutanga Lingala [Little book for reading Lingala] by De Boeck.[14][44] One century later, Lingala, which De Boeck had constructed from elements of Bangala and other Bantu languages including Bobangi, Mabale and Iboko, has 25 million speakers worldwide, and has become a lingua franca in both the D.R. Congo and the Republic of the Congo.[15]

In Canada, church groups in Victoria and Ottawa contributed to the European condemnation of the atrocities committed by King Leopold II against Congolese slave labourers, in the form of a letter written to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, calling upon Britain to "secure to the people of the Congo Free State due protection and justice", and this public pressure ultimately led in 1908 to Leopold's relinquishment, and creation of the Belgian Congo colony.[45]

1940s and Second World War[edit]

In 1939,[46] the United States purchased 1,200 tons of uranium ore[47] from the Union Minière du Haut Katanga's Shinkolobwe mine in the Belgian Congo,[48] that was warehoused on Staten Island, New York City.[49][50] The Canadian municipality of Port Hope, Ontario was site of the former radium producer and, at that time, sole North American uranium refiner, Eldorado Mining and Refining Limited, which between 1941 and 1946 provided a steady supply of refined uranium oxide to the Manhattan Project.[46][51] In 1942, the Canadian government acquired Eldorado, making it a crown corporation in 1944.[46] Eldorado's initial supplies were derived from uranium concentrates at Port Hope that had accumulated as tailings from its past radium operations, and, beginning in 1942, refined from newly mined ore shipped from its re-opened Great Bear Lake pitchblende mine in the Northwest Territories.[52] Eldorado in addition refined at Port Hope the US's Congolese ore stockpile that had been shipped from the New York storage facility, and further shipments of ore from the Congo.[49][52] The 1,100 tons of Canadian-mined uranium, and 3,700 tons from the Congo that were refined in Canada, along with 1,200 tons from Colorado,[48] comprised the six thousand tons of uranium oxide[47][53] that formed the Manhattan Project's raw materials for the fissionable cores of the uranium-235 and plutonium-239 atomic bombs that were released and exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan in August 1945, immediately killing an estimated thirty percent of Hiroshima's civilian and military population,[54] and resulting in an estimated total of 293,000 fatalities in the two cities, from both the immediate blast and long-term radiation exposure.[55]

Post-war[edit]

The Belgian Congo became, after the Second World War, one of the first of Canada's commercial partners in Africa, the first trade post outside the British Commonwealth,[45] with a trade commissioner posted in Leopoldville in 1948,[56] ranking it among Canada's top dozen trading partners; in the mid-1950s the Canadian company Aluminum Limited attempted to gain control of the construction of the Inga hydro-electric power project at Matadi on the Congo River, however they "anxiously preferred to remain discreet" to avoid "antagoniz[ing] Belgian business interests".[45]

The Royal Bank of Canada partnered in 1957 with eight other international banks in furnishing a $40 million World Bank loan to the Belgian Congo for the building of roads. In their 1962 book ISBN 0888620403 Anatomy of Big Business, Libbie and Frank Park traced a direct connection from the Royal Bank's president and vice-president's directorship of Sogemines Ltd., a Canadian investment and holding company and Belgian subsidiary, to shared directorship in the Belgian parent conglomerate, Société Générale de Belgique, which also owned the Congolese firm Union Minière du Haut-Katanga. The authors identified an extended network involving major Canadian corporations including Canadian Petrofina Ltd., Abitibi Power and Paper Company, Trans-Canada Pipe Lines Ltd., Noranda Mines Ltd., and Dominion Steel & Coal Corp. Ltd., concluding that "[e]veryone is happy; everyone is scratching everyone else's back at a profit - and profits are extracted from the labor of Congo workers who up till recently have had nothing to say about the situation".[57]

In July 1960, the newly appointed Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, made an official visit to Canada (Montreal and Ottawa), requesting Francophone technical assistance for his country,[58] however financial assistance was turned down by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.[59] During the ensuing Congo Crisis, about 1,800 Canadians from 1960 to 1964 served among the 93,000 predominantly African peacekeepers with the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC), working chiefly as communications signallers and delivering via the Royal Canadian Air Force humanitarian food shipments and logistical support.[60] The Canadian participation stemmed more from overwhelming public opinion, and not decisive action on the part of the Diefenbaker government, according to historians Norman Hillmer and Jack Granatstein.[61] However, Diefenbaker reportedly refused to comply with numerous public calls for Canada to provide humanitarian relief to 230,000 Congolese famine victims in South Kasai in 1961 ostensibly because "surplus foodstuffs should be distributed to unemployed persons in Canada" as a first priority.[45][62] Two Canadians died from non-conflict-related causes, and, out of the 33 Canadians injured in the conflict, twelve received "severe beatings" by the Congolese forces.[60] Although Patrice Lumumba dismissed the first incidences[spelling?] of these beatings, on August 18, 1960, as "unimportant" and "blown out of all proportion" in order for the UN to "influence public opinion", he attributed them a day later to the Armée Nationale Congolaise's "excess of zeal".[59] Historians have described these incidents as cases of mistaken identity under chaotic circumstances, in which Canadian personnel were confused by Congolese soldiers with Belgian paratroopers, or mercenaries working for the Katanga secession.[60][61] Only a quarter of Canada's signallers extended their six-month tours of duty to a full year, and Canadian forces reportedly found the Congolese to be "illiterate, very volatile, superstitious and easily influenced", including an instance where a Canadian Lieutenant-Colonel successfully persuaded Kivu Province's Prime Minister to accept a relief contingent from Malaysia by explaining to him that the Malaysians were capable of diverting bullets in flight away from their intended path.[60] A recent study concluded that while the Canadian government "demonstrated a greater willingness to accommodate the Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba than other Western nations" and publicly did not side with either faction, it "[p]rivately [...] favoured the more Western oriented [President] Kasavubu".[58] Canada's troops earned the trust of Joseph Mobutu, the latter visiting Canada in 1964 as leader of the Congolese National Army, during which he acknowledged Canada's support in maintaining his country's territorial integrity.[60]

Canada established formal diplomatic ties with the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1965, with Ambassador J.C. Gordon Brown taking charge of the Canadian embassy in Léopoldville.[56][63]

With funding from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the Quebec firm Gauthier, Poulin et Thériault (later Groupe Poulin & Thériault) conducted an inventory of 5.2 million hectares of Zairian forest during 1974–1976.[64][65] During the 1980s, Canada undertook a detailed inventory of Zaire's forestry resources with the aim of developing the sector,[66][67] via the Service Permanent d'Inventaire et d'Aménagement Forestier (SPIAF).

1990s[edit]

In November 1996, the first deployment of Canada's Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART), along with 354 Canadian Forces personnel, out of 1,500 originally committed, formed "Operation Assurance", with its mission to deliver humanitarian services to Rwandan refugees in eastern Zaire, as part of a Canada-led, United Nations-mandated African Great Lakes Multinational Force.[17][68][69] Raymond Chrétien, a nephew of the Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, who was Canada's ambassador to the United States and previously in Zaire from 1978 to 1981, was appointed during November and December 1996, the UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Great Lakes Region; Chrétien's role was to help defuse the tension in the region, initiate a negotiation process for the repatriation of Rwandan and Burundian refugees in eastern Zaire, and to secure a ceasefire with the leader of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFL), Mr. Laurent-Désiré Kabila.[70] Assisted under Canadian Forces Operation LEGATION,[71] Raymond Chrétien consulted with Zairian President Mobutu Sese Seko and with the leaders in Rwanda, Burundi, and neighbouring countries.[16] While Chrétien did not meet with Laurent Kabila despite requests from the latter,[72] the Canadian Lieutenant-General Maurice Baril and leader of the multinational force did meet with Kabila in Goma in November 1996, discussing food airlifts for the Rwandan refugees in eastern Zaire.[73] General Baril secured a promise from the AFDL to not fire on humanitarian relief aircraft in return for providing Kabila's forces with advance notice of these flights,[17] however Baril's convoy of Joint Task Force 2 personnel was reportedly ambushed en route between Goma and Kigali, and had to be rescued by U.S. Apache and Tomahawk helicopters.[74] Prompted in November 1996 by television images of the refugees, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien reported contacting world leaders to assemble an international military force of 15,000, including Europeans and Americans, under Canadian command, however Chrétien notes that the crisis resolved itself before a Security Council resolution had been obtained.[75] Estimates of the number of Rwandan refugees in the eastern DRC varied widely, from France counting "700,000" to Germany's "500,000", Canada's "300,000 to 500,000",[76] and the United States NGO, Human Rights Watch, assuming only a few tens of thousands.[24] In mid-December 1996, both Raymond Chrétien and Maurice Baril recommended the withdrawal of the UN peacekeepers, based on evidence of a mass repatriation of the Hutu refugees, and then-assistant deputy foreign minister Paul Heinbecker announced the Government of Canada's decision to end the mission on December 31.[77] Despite these actions, according to the Belgian journalist Colette Braeckman, a half million Rwandans had in fact migrated further east into the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) rather than repatriating.[78] In June 2003, General Maurice Baril served as Special Representative to UN Secretary-General Koffi Annan to mediate with the DRC government in forming a new army,[18] when DRC president Joseph Kabila signed a power-sharing agreement with rival factions.[79][80]

The journalist and former Médecins sans Frontières (Canadian Branch) communications director during the 1996 Congo/Zaire crisis, Carole Jerome, stated in 2001 that:

Washington had absolutely no desire to go in and stop the carnage wrought by Kabila. Instead it prevailed upon the Canadians to lead this doomed mission, and they were willing dupes. Jean Chrétien had been moved by sights of killings on TV, and genuinely wanted to do something. Wading into this we had the prime minister's nephew and ambassador to the US, Raymond Chrétien, who was hopelessly unprepared. When he suggested the solution was setting up a hospital in Rwanda, where MSF had been running a hospital for years, one of our doctors moaned, 'Oh dear, the man does need some work'. Meanwhile, the only ones who actually did want to intervene seriously were the French, just as they had finally done themselves in Rwanda, with Operation Turquoise.[81]

According to Paul Heinbecker, who later became Canada's Ambassador to the United Nations, the "Americans, pursuing their own obscure agenda in the Congo, offered much advice but little assistance, and the British, unwilling to play second fiddle to 'colonials' and supporting the Americans reflexively, were actively unhelpful [...] Canada did not then have the military capacity itself to carry out a major combat operation half a world away".[82] Other sources document copious evidence that the United States had direct involvement in supporting Laurent Kabila and the AFDL in overthrowing the Mobutu regime.[83][84][85] Reflecting in 2008 on his work experiences in Zaire, Raymond Chrétien opined that "Mobutu who was a great African leader but living in a very corrupt environment, a very difficult environment; he was a skilful man at keeping his country together".[86]

In Vancouver, in June 1997, Mbaka Kawaya, the chair of Congo's newly appointed Générale des carrières et des mines (Gécamines) led a Congolese delegation that met with Canadian mining companies active in the Congo, including Harambee Mining Corp., International Panorama Resource Corp., and Tenke Mining Corp.[87] In 1998, the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) and Canada's Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade co-sponsored, under the organisation of Joe Clark, a visit by the DRC Minister of Mines, Frederic Kibassa-Maliba, for meetings with mining companies at the PDAC's annual convention in Toronto.[88] During his Canada mission, Minister Kibassa-Maliba was also scheduled to meet with Canadian NGOs at Montreal offices of the Canadian engineering firm SNC Lavalin, however, this meeting was reportedly canceled by Canada's Foreign Affairs department following protests made by dozens of representatives from a banned Congolese opposition party, the UDPS (Union for Democracy and Social Progress).[89]

During 1997–1998, former Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark was employed by the Vancouver, Canada-based First Quantum Minerals as a political adviser to the newly established Congolese president, Laurent-Désiré Kabila.[21][22][90] Clark also co-directed a 58-member election observers team from the Carter Center during the DRC's 2006 elections.[91][92] From 1993 to the present, former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney has been on the board of directors of Barrick Gold Corporation, serving as Chairman of the company's International Advisory Board,[93][94] during which time Barrick acquired gold mining concessions in the D.R. Congo in 1996,[95] and relinquished them in 1998.[96][97] According to Barrick's chairman, Peter Munk, Mulroney was recruited because "[h]e has great contacts. He knows every dictator in the world on a first name basis".[98] A third Canadian ex-Prime Minister, Jean Chrétien, held meetings with D.R. Congo politicians in Kinshasa during January 2005.[90][99] Since 2008, former prime minister Paul Martin has been co-chair of the Governing Council of the Congo Basin Forest Fund, a multi-donor sustainable and community forestry initiative which was founded to protect the Congo Basin rain forests that are shared by the D.R. Congo and nine other central African nations.[100]

Robert S. Stewart, a Canadian-Swiss dual citizen and graduate of the University of Manitoba who had worked with Canada's foreign service in Africa for seven years[101] before entering the private sector on African mining and petroleum projects,[102] served as a consultant for the American engineering firm Bechtel International Corporation and drafted Bechtel's $5 bn. reconstruction plan for the DRC known as "An Approach to National Development. Democratic Republic of Congo".[24][103] The Bechtel plan was presented to the Congolese government in November 1997 and centred on natural resource-based partnerships in copper and cobalt, diamonds, tin, gold in the east of the country, along with hydro-electric development, forestry, oil and agriculture elsewhere.[104] The Congolese government rejected the Bechtel proposal, devising its own three-year development plan, which it brought to a World Bank-sponsored "Friends of the Congo" meeting of seventeen countries as well as international institutions in Brussels in December 1997; donors pledged to commit $450m. of the $575m. that the DRC team was requesting from them, out of a total plan budgeted at $1.7bn.[105][106] Also present at the December 1997 meeting in Brussels were the Canadian-registered mining companies Barrick Gold, America Mineral Fields, Tenke Mining, and International Panorama Resource Corp.[107] In 1997, Stewart also became advisor, and then briefly in 1998, chairman of America Mineral Fields Inc., a company headquartered in Arizona, U.S.A., but incorporated in Canada (renamed Adastra Minerals Inc. in 2004).[108] After the Congolese government's cancelation of America Mineral Fields' tender for the Kolwezi copper/cobalt tailings concession in early 1998,[109] Colonel Willy Mallants, a former Belgian advisor to Mobutu and in 1996–97 economic adviser to Laurent Kabila's Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo, and Robert Stewart announced in Brussels, in May 1998, the establishment of the "Conseil de la République Fédérale Démocratique du Congo", with Stewart as "Economic, Industrial, Diplomatic and Financial Counsellor to the Council", with the aim to overthrow President Laurent Kabila within one year's time.[24][110][111] At the Non-Aligned Movement summit in South Africa in September 1998, Stewart was identified as an advisor to the Council of the Federal Democratic Republic of Congo, a group of exiled Congolese technocrats that sought to restore democracy in their country, and Stewart claimed that a relative of Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe had been granted Stewart's DRC mining concessions.[23][112][113] While Stewart claimed at this meeting that President Kabila had "asked [American Mineral Fields] for bribes", American Mineral Fields denied this, adding that Stewart was dismissed shortly following his appointment.[114] Stewart in 2008 was director of the South African-based TransAfrican Minerals Ltd., which reported copper, cobalt and gold holdings at the Kipushi Project in the DRC,[115] and in 2009, Stewart was on the board of directors of the British Columbia-based junior company, ICS Copper Systems (now Nubian Resources Ltd.) which holds a stake in the Musoshi Tailings Project.[116]

20th century[edit]

Since 1999, the Canadian armed forces contingent, dubbed "Operation CROCODILE", working with the United Nations MONUSCO peacekeeping force has not exceeded one dozen personnel, with the exception of 2003 when fifty Canadian Forces staff and two Hercules aircraft were deployed at the request of the UN to Bunia.[117] From 1999 to 2008, Canada reportedly provided at least $20m. in support to peacebuilding exercises in the D.R. Congo, including for the 1999 Lusaka accord, the Inter-Congolese Dialogue, the Group of Friends of the Great Lakes Region, the 2006 elections, and the 2008 Goma Peace Process.[118]

After having its gold properties expropriated by the Congolese government in 1998, Banro Resources successfully sued the DR Congo government in 2000 for $240m., which overturned a previous decision by a Congolese court,[119] and involved the World Bank's International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes in Washington, D.C.[120]

Following earlier management of the D.R. Congo's state-owned mining enterprise Gécamines by the Zimbabwean Billy Rautenbach (1998–2000) and the Belgian mining executive, George Arthur Forrest (1999–2001),[121] the World Bank supported the appointment of Canadian corporate lawyer Paul Fortin as managing director of the parastatal in 2005, where he remained until his resignation in 2009.[26][122] Fortin's tenure saw the negotiation of a mining contract originally valued at $6 billion in Katanga Province with Chinese investors, and the Congolese government's "revisitation" of mining agreements accorded under previous regimes, including ones signed with Canadian mining firms.[25]

Development co-operation[edit]

From 1960 to 2009, Canada committed a total of US$1.2 billion (constant 2008 dollars) in bilateral (country-to-country) development assistance to the D.R. Congo, of which $0.9 bn. (76%) was actually disbursed. This was a lower disbursement rate than for Canada's aid to all recipient countries, 87% ($99bn. out of $113 bn.).[1] Although exact multilateral aid figures (to the African Development Bank, International Development Association, various UN agencies, etc.) from donor to recipient countries are not reported, the OECD has imputed these values, and they suggest that a higher proportion of Canadian aid to the DRC has gone through the latter channels than for most donor countries (29% vs. 26%). Total OECD Development Assistance Committee disbursements exceeded commitments by 13% over these five decades mainly because commitment figures were not reported until the year 1966 (and imputed multilateral data began in 1975). Canada reportedly provided US$10,000 in grants to Congo (Kinshasa) in each of the years 1960 and 1964 (approximately 0.1% of the total aid), in addition to financing faculty posts and university bursaries, and providing twelve Canadian technical assistance staff in the field of education.[123] Although only 7% of total Canadian bilateral aid to the DRC has been in the form of loans, Canada has until recently carried higher tied aid ratios than most OECD DAC members, such that a large portion of the total Canadian aid volume was spent on Canadian goods and services; only in the last decade has the tying status declined, from 75% in 2000, to just 2% in 2009.[124]

From 2000 to 2007, Canada canceled a total of CAN$79.1 m. in bilateral debt owed to it by the D.R. Congo.[125] The above table shows that virtually all of the US$85 m. (constant 2008 US dollars) in loans made by Canada to the DRC occurred during the 1970s and 1980s. Export Development Canada has reported interest income of C$49 million from the Government of Canada relating to debt relief to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[126]

During the period 1995 to 2009, Canada committed a total of US$395m. in constant 2008 dollars, for bilateral official development assistance (ODA) to the D.R. Congo, representing 2.4% of the $16.6bn. commitments to the DRC from all OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors.[127] Canada's actual aid disbursements were two-thirds of its commitments, with available data for 2002–2009 showing Canada to have provided a total $202m., or 1.4% of total DAC disbursements of $14.7bn.[127] Canadian ODA disbursements to the DRC represented 1.1% of the US$18.7bn. in total Canadian ODA disbursements to developing countries over 2002–09, and DRC aid from Canada was only one-half the contribution level that Canada made among all donors to developing countries, 2.7%.[127]

Canada ranked ninth-highest both in terms of total and per capita (donor nation) ODA disbursements to the DR Congo over 1960–2009, and in terms of ODA per Congolese citizen. In other words, when Canada's total direct aid to the DRC is divided by the Canadian population in 2009, each Canadian effectively provided $26 to the DRC over the last half-century, and Canada collectively provided $14 for every Congolese citizen, or about one-quarter of a dollar for each of the 66 million Congolese per year. In 2001/2002, the D.R. Congo was the tenth-largest recipient of Canadian bilateral ODA flows, at Cdn$25.2m.,[128] in 2004/2005, it was eighteenth (Cdn.$28.3m.),[129] and in 2007/2008 it had fallen to the twenty-fifth position (Cdn$19.1m.).[130] It rose to sixteenth position in 2009/2010 (Cdn.$37.3m.)[131] In earlier decades, the D.R. Congo (Zaire) ranked below twentieth (1960–61), thirteenth (1965–66), below twentieth (1970–71 and 1975–76), eighteenth (1980–81), fifteenth (1985–86), eighteenth (1990–91), and below twentieth (1995–96) in Canadian bilateral assistance.[132] In terms of overall development assistance (country-to-country, multilateral and debt relief), the D.R. Congo ranked fourteenth in 2009/2010 (Cdn$.), in the company of eleven other African nations in the top 20 recipients of Canadian aid that year, and fifth-highest in bilateral humanitarian aid receipts (Cdn.$22.7m.).[133] Nevertheless, when the Canadian government announced in 2009 that it would begin concentrating eighty per cent of its international assistance resources on twenty countries, the D.R. Congo was excluded from the seven African designees.[134] In terms of annual net ODA per capita from all donor nations, Congo/Zaire has gone from receiving 75% greater than the average for all sub-Saharan African nations during the 1960s (eighteenth-highest, US$5.9 in aid per Congolese per year, compared to US$3.8 per sub-Saharan African, current dollars), down to 82% less than the regional average in the 1990s (second-lowest, $6.8/Congolese vs. $28.5/sub-Saharan-African), and recovering to 27% below the average during 2000–2008 (twelfth-lowest, $29.9/Congolese vs. $38.8/sub-SaharanAfrican).[135] The nadir in the 1990s followed the massacre of Lubumbashi student protesters in May 1990, when Belgium, the European Commission, Canada and the United States withdrew all except humanitarian aid to Zaire.[136]

The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) has reported involvement in 108 projects in the DRC between 1999 and early 2011, in the overlapping sectors of democratic governance (34), emergency assistance (33), private sector development (31), health (26), education (11), environment (10), and peacekeeping (5).[137]

In 2011, the Canadian Council for International Co-operation recorded a total of fourteen Canadian civil society groups as active in the D.R. Congo.[138]

Since 1984, Terre Sans Frontières, headquartered in La Prairie, Quebec, reports that it has delivered CDN$10 m. in aid projects to the Upper-Uele region of northern DRC, focusing on improved access to health, safe drinking water, education, and community economic development.[139][140] Oxfam-Québec, present in the DRC/Zaire since 1984, in 2008 was collaborating with 16 Congolese counterpart organisations, employing two hundred Congolese nationals and fourteen Canadian volunteers in 27 development projects mainly in Orientale and Kivu provinces.[141][142] L'Entraide missionnaire, based in Montreal, has participated since 1989 in missionary and development NGO working groups focusing on Democratic Republic of Congo (Table de concertation sur les droits humains au Congo-Kinshasa) and the African Great Lakes regions (Table de concertation sur la région des Grands-Lacs), and has regularly presented evidence on Congolese human rights issues at sessions of the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development.[143][144]

The Quebec-based Fondation Biotechnologie pour le développement durable en Afrique (BDA) is training Congolese farmers in Equateur and Bas-Congo to cultivate and harvest medicinal plants, including the antimalarial-containing margosa and armoise plants.[145]

Of the US$214 million in Canada's imputed multilateral commitments to the D.R. Congo over 2000–2009,[1] at least one-half (approximately US$103 million) has returned directly to the Canadian economy, in the form of Congolese-related World Bank consultancy and supply contracts to Canadian firms, International Finance Corporation investments in Canadian companies active in the DRC, and one Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency investment to a Canadian firm mining copper in the DRC.[146] CIDA's annual statistical reports for fiscal years 2000–2001 to 2009–2010 show a total of Cdn.$103.4 m.,[147] or US$84.3 m.,[148] in multilateral development assistance provided to the D.R. Congo by federal government departments other than CIDA; these funds principally derived from the Department of Finance's contributions to international financial institutions.[149] Over the same period, CIDA made direct contributions totalling Cdn$14.4m. (US$10.4 m.) to eight D.R. Congo-related projects, for which the executing agency partner was the World Bank or International Monetary Fund, including the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa, the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control, and the Demobilization and Reintegration of Ex-Combatants.[137] During the 2000s, financial inflows to Canada from World Bank group contracts in the DRC (US$103 m.) exceeded Canada's World Bank and IMF contributions to the DRC (US$95 m.) by eight per cent.

Trade[edit]

Based on the HS6 Harmonized System international commodity classification, Canada's principal exports to the D.R. Congo over the last two decades have consisted of articles of second-hand clothing and other used textiles, followed by food (chiefly wheat, milk powder, and dried peas), and mining equipment and supplies.[150] There was little fluctuation in the export profile between the two most recent decades.

| Principal Canadian Exports to the D.R. Congo | ||||||

| current U.S. dollars, millions | percentages | |||||

| 1990–2000 | 2001–2010 | 1990–2010 | 1990–2000 | 2001–2010 | 1990–2010 | |

| Second-hand clothing | $40.66 | $69.37 | $110.03 | 45.3% | 47.1% | 46.4% |

| Food products | $7.64 | $15.18 | $22.82 | 8.5% | 10.3% | 9.6% |

| Vaccines and Medical supplies | $0.49 | $0.00 | $0.49 | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| Mining equipment and supplies | $5.10 | $13.57 | $18.67 | 5.7% | 9.2% | 7.9% |

| Aircraft | $18.69 | $0.00 | $18.69 | 20.8% | 0.0% | 7.9% |

| Other | $17.19 | $49.27 | $66.46 | 19.1% | 33.4% | 28.0% |

| TOTAL | $89.76 | $147.39 | $237.15 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| TOTAL, DRC | $89.76 | $147.39 | $237.15 | 0.004% | 0.004% | 0.004% |

| TOTAL, AFRICA | $9,919 | $17,154 | $26,168 | 0.49% | 0.50% | 0.48% |

| TOTAL, WORLD | $2,041,233 | $3,425,514 | $5,466,747 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Source[150]

During 2003–2007, Canada ranked between fourth- and seventh-highest in dollar value, among nations exporting worn clothing and other worn textiles, and in 2007 its global exports of this commodity were valued at US$187m.[151] Canada's used clothing exports to the DRC, US$9.7m. in 2007,[150] represented 3.5% of Canada's global total, and 28.1% of DRC's estimated used clothing imports of US$34.5m.[151] In 2001, humanitarian groups working in rebel-occupied areas of the DRC reported to a United Nations Panel of Experts of "women in some villages who have simply stopped taking their children to the health centres because they no longer possess simple items of clothing to preserve their dignity".[152]

Cobalt from the DRC dominated Canadian imports, however it, petroleum and diamonds were only prominent during the 1990s. The value of imports in the 2000s, chiefly from tropical wood products, was only 2.5% of the previous decade's.[153]

| Principal Canadian Imports from the D.R. Congo | ||||||

| current U.S. dollars, millions | % | |||||

| 1990–2000 | 2001–2010 | 1990–2010 | 1990–2000 | 2001–2010 | 1990–2010 | |

| Cobalt | $151.32 | $0.42 | $151.74 | 91.5% | 10.3% | 89.5% |

| Diamonds | $2.71 | $0.43 | $3.14 | 1.6% | 10.5% | 1.9% |

| Lumber products | $0.35 | $1.39 | $1.74 | 0.2% | 33.8% | 1.0% |

| Petroleum | $8.96 | $0.00 | $8.96 | 5.4% | 0.0% | 5.3% |

| Other | $2.06 | $1.86 | $3.93 | 1.2% | 45.4% | 2.3% |

| TOTAL | $165.41 | $4.10 | $169.51 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| TOTAL, DRC | $165.41 | $4.10 | $169.51 | 0.009% | 0.000% | 0.003% |

| TOTAL, AFRICA | $13,734 | $59,038 | $72,772 | 0.8% | 1.9% | 1.5% |

| TOTAL, WORLD | $1,826,889 | $3,118,985 | $4,945,874 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Source[153]

When sorted according to the top twenty-five industry categories between 1992 and 2009, "other recyclable material[s]" (NAICS code 41819) head the list in every year except for 1995, representing 54.5% of all Canadian exports to the DRC, or US$119m. out of $219m. in nominal dollars.[154] The mining industry ranked second, comprising 5.0% of exports to DRC, although during 2007 and 2008, it reached 9.9% and 14.4%, respectively.[154]

Investment[edit]

In 2009, the D.R. Congo's Prime Minister reported that there were 22 Canadian companies operating in the country, employing 13,000 persons in the mining and energy sectors.[155] Although earlier years' figures were suppressed to meet statutory confidentiality requirements, in 2010, the total Canadian direct foreign investment in the D.R. Congo was estimated by Statistics Canada to be valued at $123 million Canadian compared to $557 million Canadian investment in Ghana and $140 million in Nigeria, out of total 2010 Canadian investments in Africa of $3.05 bill.[156] The stock of total Canadian direct investment in Africa rose from C$2.2 billion in 2003 (0.5% of total Canadian investment abroad)[157] to C$5.6bn. in 2008 (0.9% of total FDI) and C$5.1bn. in 2009 (0.9%).[158] Canada represented roughly five percent of the UNCTAD estimate for global FDI stock in Africa of US$72.9bn. in 2008.[159] Global FDI stock in the DR Congo was reported to have risen from US$617m. (2000) to US$2.5bn. (2008) and US$3.1bn. in 2009.[159]

Non-extractive sectors[edit]

The Government of Canada's export credit agency, Export Development Canada, reported in 2008 furnishing the Quebec-based publisher Beauchemin International with a bank guarantee valued at under CAD1m. for the sale of school manuals to the government of the D.R. Congo, financed through the Royal Bank of Canada.[160] Beauchemin was awarded a US$4.9m. contract by the World Bank's International Development Association in 2009 for the provision of primary school mathematics textbooks to the D.R. Congo.[161] Export Development Canada has also reported holding, since 2003, between C$44 million (2003) and C$49 million (2009) in impaired loans, received from the Government of Canada, and designated as reimbursement for debt relief to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[126][162]

The World Bank Contract Awards Search database records a total of 41 contracts awarded to fifteen Canadian firms and nine individuals between 2001 and March 2011, totaling US$26.5 m., out of a total of 1,157 contracts (US$1,711.4 m.) awarded globally for projects specifically designated for the "Democratic Republic of Congo". All but one of the Canadian contracts were for consultancy services, the exception being the aforementioned Beauchemin textbooks supply contract, and all were financed via the International Development Association arm of The Bank.[163]

One "successful partnership" cited by a Trade Commissioner with Canada's diplomatic mission in Kinshasa took place over 1993–2004, when CIDA, the World Bank, and Société nationale d'électricité (SNEL), the Congolese state electrical energy agency, funded a partnership between the Canadian company Berocan International, Inc., and a Congolese counterpart, Projelec, which provided electrification for 2,500 subscribers and public lighting in the capital city of Kinshasa.[164] Through CIDA and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Montreal-based Berocan received a total of CDN$890k. in federal government support during 1995–1999.[165][166][167][168] Projelec also partnered in 2009 with Rosemère, Quebec-based LTCC Hydro in a micro-hydroelectric power service on the Mpioka River to serve the Kimbanguist Christian community of Nkambe in Bas-Congo province.[169]

MagIndustries Corp. (formerly Magnesium Alloy Corp.), a magnesium producer headquartered in Toronto, through its subsidiary, MagEnergy, refurbished turbines at the DRC's INGA II hydroelectric dam, and began receiving from DRC's electric utility, SNEL, in 2010 payments totaling U$240m. following a "protracted dispute"; they also report having carried out work at the Busanga hydroelectric site in Katanga Province.[170] The company also claims that it holds a designated right to supply energy to the DRC's existing regional and international power grids.[171] MagEnergy also reported in 2007 contracting the Canadian engineering firm SNC Lavalin to prepare a technical review in conjunction with MagEnergy's participation option in the DRC's Zongo II hydroelectric site.[172]

Montreal-based SNC Lavalin reported in 2010 that it was awarded EP contracts (engineering and procurement) for mining projects in Katanga Province.[173] The 2002 US$0.2m. World Bank contract related to the restoration of copper and cobalt mines.[174] In 2003, the company reported completion of a World Bank-funded environmental impact study and resettlement plan for Congolese citizens affected by the construction of electrical transmission lines, and SNC Lavalin updated the study in 2008,[175] which involved the DRC utility company SNEL's participation in the Southern African Power Pool.[176] SNC Lavalin also supplied the DRC government in 2008 a pre-feasibility study, reportedly supported under a CIDA grant,[177] for the DRC's INGA III hydroelectric facility,[178] a proposal which SNC valued at $3.5bn., with a generating capacity of 4,320 megawatts.[179]

Toronto-based Feronia Inc., a large-scale farmland and plantation operator, acquired in 2009 a 76% interest in palm oil plantations that were previously owned by Unilever, on ten thousand hectares of arable farmland in Équateur, Orientale and Bas-Congo provinces; the company reported production of four thousand tonnes of crude palm oil, total DRC land concessions of one hundred thousand hectares, and began cultivation of edible beans in Bas Congo in 2010.[180] In 2010, Toronto-based Navina Asset Management (name changed to Aston Hill Asset Management in 2011) held 13% and 10% stakes, respectively, in Plantation et Huileries du Congo and Feronia Inc., and fixed income assets in the Democratic Republic of Congo comprised Cdn$1.8m., or 13% of the portfolio's net asset value.[181]

The American engineering consulting firm Aecom, which acquired the privately owned Montreal-based firm, Tecsult International, in 2008 for its hydropower expertise[182] and employs 2,000 people in the province of Quebec,[183] was awarded in 2011 a $13.4m. African Development Bank contract to undertake a feasibility study into the Grand Inga hydroelectricity site in the DR Congo.[183][184]

Laval, Quebec-based Corporation Carbon2Green received preliminary authorisation from the Congolese government in 2008 to undertake the cultivation of the biofuel crop, Jatropha, on degraded soils unsuitable for food production in Bandundu Province, to supply rural electrification projects in the DRC, and the company plans to explore methane gas recovery from Lake Kivu.[185] They are seeking to raise C$27.6m. in investment for these projects.[186]

Mining[edit]

A 2006 survey published by the World Bank estimated that the D.R. Congo holds the world's largest known cobalt resources, and diamond resources by volume, and the second-largest copper resources after Chile,[187] and the majority of Canadian-domiciled mining companies active or previously active in the DRC are either exploring for, developing or undertaking large-scale mining of these copper and cobalt resources. Four Canadian companies, Anvil Mining, First Quantum Minerals, Lundin Mining, and Katanga Mining Limited have been engaged in industrial copper and cobalt extraction operations during 2000–2010, and another eight junior Canadian mining companies including Ivanhoe Nickel & Platinum Ltd. and Rubicon Minerals Corporation, as of early 2011, were reporting active holdings of copper and cobalt concessions in Katanga province. Nine Canadian junior mining companies, among which are Kinross Gold Corp., previously held copper and/or cobalt concessions, but have since abandoned them, or had them acquired by other Canadian or South African firms.

Since 1996, Banro has held gold concessions in South Kivu and Maniema provinces of the DRC,[188] while six other Canadian companies previously owned Congolese gold properties, including Barrick Gold (1996–1998),[95][96] and Moto Goldmines (2005–2009). In the diamonds sector, Montreal-based Emaxon Financial International Inc. is currently active, while seven other Canadian junior companies reported previous ownership of properties in the DRC during 2001–2009, including Canaf Group and BRC DiamondCore. Montreal-based Shamika Resources is exploring for tantalum, niobium, tin and tungsten in the Eastern DRC and Loncor Resources is exploring for gold, platinum, tantalum and other metals. Two Canadian-registered companies own petroleum concessions in the DRC, Heritage Oil, whose founder and Chief Executive Officer is Tony Buckingham, and EnerGulf Resources.

The Government of Canada's mining ministry, Natural Resources Canada estimated that in 2009, Canadian-owned mining assets in the D.R. Congo were valued at Cdn.$3.3 billion, a ten-fold increase over 2001, and represented one-sixth of total Canadian mining assets on the continent of Africa, the second-highest share after Madagascar.[189]

Of the six D.R. Congo projects, valued at a total of $59.7m., that have been funded up to early 2011 by the World Bank Group's Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), the very first was made in 2005 to Canada and Ireland as co-investors, on behalf the Dikulushi Mine held by Anvil Mining in Katanga Province; the project's value of US$13.6m. was a guarantee against political risks including expropriation and civil disturbance.[190] Four of the nine D.R. Congo projects sponsored or proposed for sponsorship by the World Bank's International Finance Corporation up to early 2011 were for Canadian-owned companies active in the DRC: to Kolwezi/Kingamyambo Musonoi Tailings SARL owned by Adastra Minerals Inc. ($50.0m., invested in 2006),[191] Africo Resources Ltd. (acquisition of Cdn.$8m. in Africo shares, invested in 2007),[192] and Kingamyambo Musonoi Tailings SARL as acquired by First Quantum Minerals, proposed in 2009 at a value of US$4.5 m. in equity funding.[193][194]

In 2011, Canada's Fraser Institute annual survey of mining executives reported the DRC's ranking of its mining exploration investment favourability fell from eighth-poorest in 2006 down to second-poorest in 2010, among 45 African, Asian and Latin American countries and 24 jurisdictions in Canada, Australia and the United States, and this was attributed to "the uncertainty created by the nationalization and revision of contracts by the Kabila government".[195]

Immigration and remittances[edit]

In Canada's 2006 census, 14,125 immigrants born in the DRC were recorded, half (6,910) of whom arrived since 2001, and this latter group comprised 0.6% of Canada's immigrant intake over 2001–2006,[196] while the DRC population in 2005, 59.1 m., represented 0.9% of the world population.[197] The 3,854 DR Congolese immigrants settling in the province of Quebec from 2003 to 2007 ranked fourteenth highest, or 1.8% of immigrant intake from all countries.[198] Of 285 immigrants from the DRC who had earned a degree there in a provincially regulated occupation in Canada such as medicine, engineering or law, only 21% were employed in that profession in Canada, close to the average match rate for all immigrants of 24%.[199]

Congolese refugees in Canada have come typically from the provinces of Kasai, Bandundu, Bas-Congo and the Kivus, belonging to the Luba, Kongo, Mbala, Hunde and Nande ethnic groups, and about four-fifths make their home in Montreal.[200] Annual intake of Congo refugees rose in Canada from under forty during the 1980s to over 700 in 1997; sixty percent of these refugee status applications have been accepted by the Canadian government, and 35-40% of refugee families reported being victims of torture or imprisonment in the DRC.[200] The D.R. Congo is one of three African and three Latin American countries affected by internal conflict with which Canada presently has a moratorium on deportation of denied refugee status claimants, based on Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.[201][202] However, there have been reports citing Canada Border Services Agency data that DRC and other moratoria nationals who were asylum claimants presenting themselves at the U.S.-Canada border have been refused entry.[203][204]

Refugee status was granted by Canada to fifty-five hundred, female, D.R. Congolese asylum-seekers between 1993 and early 2009, of which forty-five percent involved claimant applications made overseas.[205]

A World Bank survey of educational qualifications of immigrants to six high-income countries showed that DR Congolese immigrants to Canada have significantly higher levels of educational attainment than the average for all immigrants to Canada, where 71.0% of 313 Congolese immigrants in 1975 possessed a "high" educational level compared to just 40.5% for the overall Canadian immigrant sample of 2.76 m. persons, while in 2000, 83.5% of 5,505 Congolese immigrants had attained the "high" educational level, compared to 58.8% for the entire 4.60m. immigrant sample; in the 2000 sample, Canada ranked highest among 195 countries with 51.5% of its labour force having obtained the "high" level of education, while the D.R. Congo was ranked 17th-lowest, with a corresponding ratio of 1.3%.[206] This suggests that not only did all Canadian immigrants in 2000 hold significantly higher educational qualifications than native-born citizens, but Congolese immigrants were nearly twice as likely as native Canadians to be highly educated.

State visits[edit]

In April 2010, Michaëlle Jean, then Governor General of Canada, paid a three-day state visit to the D.R. Congo, meeting with President Joseph Kabila Kabange and touring the CIDA-funded Ngaliema Clinic in Kinshasa, and visiting the North Kivu province governor Julien Paluku Kahongya, Canadian members of the UN peacekeeping force MONUSCO and the partially Canadian-funded HEAL Africa Hospital, in Goma.[207]

Recent relations[edit]

During 2008–2009, retired Canadian Major Philip Lancaster served as Chief of the United Nations Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) initiative for MONUSCO in Goma in the eastern DRC.[20] In early 2010, Dr. Lancaster was Coordinator of the UN Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[19]

In 2009, the D.R. Congo's Prime Minister, Adolphe Muzito, reported that Canada "contributed enormously to the development" of his country, with 22 Canadian companies employing 13,000 persons in the energy and mining sectors.[2]

DRC's rank among recipients of Canadian bilateral development assistance has fluctuated between tenth and twenty-fifth highest since 1960, and Canada was ninth among country donors to the DRC over 1960–2009, with total disbursements of US$892 million (constant 2008 dollars) accounting for 2.8% of Congolese country-to-country aid receipts.[208] Canada's bilateral aid included a total of US$84.5 mill. (constant 2008 dollars) in bilateral loans to the former Zaire during 1972 to 1987,[1] however over 2003–2006, Canada provided Cdn.$79.1 mill. (US$56.9 m.) in bilateral debt relief to the DRC under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative.[149]

In May 2010, following two earlier rejections, Canada declined a United Nations request for Lieutenant-General Andrew Leslie to command the MONUSCO peacekeeping force comprising twenty thousand troops from twenty countries in Democratic Republic of the Congo; Canada has posted about a dozen soldiers with the mission.[209]

Louise Ramazani Nzanga, the DR Congo's Ambassador to Canada from 2003 to 2010, thanked Canada in a farewell address for its support during the DRC's regional conflicts, in the 2006 Congolese elections, and its support through the Canadian International Development Agency; Dominique Kilufia Kanfua replaced Ms. Nzanga in 2010 as Ambassador to Canada.[210]

In July 2010, despite Canada temporarily delaying a World Bank decision to cancel $12.3 bn. of the DR Congo's foreign debt on the grounds of the DRC's 2009 annulment of Canadian company First Quantum's $750 million copper-cobalt Kolwezi mining agreement, and Canada abstaining along with Switzerland from the vote,[7] the Bank nevertheless approved the debt write-off decision.[211] The DR Congolese Information Minister, Lambert Mende, was quoted as saying that "Canada did something that disrupted our efforts as it took a lot for us to meet the debt relief conditions, but we have no problem with them and we will follow our relations with them as usual".[9] In its November 2010 press release, the Paris Club, of which Canada is one of 19 permanent members, announced that it had approved cancellation of $6.1 billion. and rescheduling of another $1.5 billion of DRC's total external debt of $13.7 billion,[212] but expressed "concern over the business environment", noting that "[t]he case of the DRC raised the issue of non cooperative behavior from some litigating creditors".[213]

Canada's Ambassador to Congo (Kinshasa), Anna Sigrid Johnson, met with the Congolese foreign minister Alexis Thambwe Mwamba in August 2010 and discussed the maintenance of security arrangements for Canadian investments in the country as well as on the validation and respect for Canadian contracts signed according to Congolese and international law in the mining, energy and commerce sectors.[214]

In November 2010, the Canadian Association Against Impunity, composed of representatives from the Canadian Centre for International Justice, RAID and Global Witness in the United Kingdom, and ASADHO and ACIDH in the D.R. Congo, initiated a class action complaint in a Montreal court on behalf of relatives and survivors of killings committed by the Congolese military of over seventy unarmed civilians in Kilwa, Katanga Province during 2004, for which the Canadian-incorporated Anvil Mining allegedly provided logistical support.[215]

In December 2010, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police deployed five unarmed police officers to the United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for a period of one year.[216]

Canada has since 2004 abided by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1533-imposed sanctions on arms exports, military technical assistance to the DRC, in addition to assets freezes and travel bans to, in December 2010, 24 Congolese, Rwandans and Ugandans who are suspected of involvement in illegal armed groups or criminal activity, and are listed under UN Security Resolution 1952.[217]

Stéphane Bourgon, a former Canadian Forces and International Court of Justice lawyer from Repentigny, Quebec, during 2009 and 2010 represented former military leader and head of the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), Laurent Nkunda against allegations of war crimes at a military tribunal in Rwanda.[27] Bourgon was appointed in 2010 as a communications director with the Canadian government-supported Rights & Democracy (International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development).[218] In September 2010, the Congolese-Canadian lawyer Nicole Bondo Muaka, a member of the Toges Noires (Black Gowns) human rights group, was detained for one week by Congolese authorities on suspicion of collusion during an attack on DRC President Joseph Kabila's motorcade by members of an outlawed opposition party.[219] Following four decades in the federal Canadian civil service, former Canadian ambassador to Zaire and UN Special Envoy Raymond Chrétien joined in 2002 the Canadian international corporate law firm of Fasken Martineau as a strategic advisor.[220]

See also[edit]

- Foreign relations of Canada

- Foreign relations of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Canadian mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. "Aggregate Aid Statistics: ODA by recipient by country", OECD International Development Statistics (database). While disbursements cover the full 1960–2009 period, commitments data were only reported by the OECD from 1966 to 2009, and for imputed multilateral aid from 1975 to 2009. doi:10.1787/data-00061-en (accessed March 12, 2011).

- ^ a b République Démocratique du Congo. Cabinet du Chef de l'État. 2009. "Le Premier ministre informé des activités des sociétés canadiennes en RDC", 10 juin 2009, http://www.cinqchantiers-rdc.com/article.php3?id_article=1800 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 28, 2011).

- ^ a b Miron, Michel. 2010. "Africa: Cumulative Canadian Mining Assets" (calculated at acquisition, construction or fabricating costs, and includes capitalized exploration and development costs, non-controlling interests, and excludes liquid assets, cumulative depreciation, and write-off), Minerals and Metals Sector, Natural Resources Canada, internal document.

- ^ Natural Resources Canada. "Canada's International Presence in 2009". Canada's Mining Assets Abroad Information Bulletin, February 2011. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Canadian mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo#Canadian & multilateral public investments

- ^ Government of Canada. "Canada - Democratic Republic of Congo Relations". The Embassy of Canada, Kinshasa 1, Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ^ a b Anonymous. 2010. "Canada cool to Congo", The Province. Vancouver, B.C., July 2, 2010. pg. A.35.

- ^ Government of Canada. Department of Finance. 2011. Canada at the IMF and World Bank Group 2010. Report on Operations under the Bretton Woods and Related Agreements Act, "Canada's Engagement at the IMF", (accessed May 11, 2011).

- ^ a b Bouw, Brenda. 2010. "Congo wins debt relief despite Canadian concerns", The Globe and Mail, July 2, 2010, pg. A.13.

- ^ Radio Okapi. 2009. "Le Canada réticent sur le climat des affaires en RDC", Echos d'économie programme, November 29, 2009, from 10:58 to 17:34 of audio file, http://radiookapi.net/emissions-audio/2009/11/29/le-canada-reticent-sur-le-climat-des-affaires-en-rdc/ Archived 2011-05-05 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 30, 2011).

- ^ Anonymous. 2010. "Canada requests delay in Congo debt relief", Wed Jun 30, 2010, 5:48am GMT, [1] (accessed April 26, 2011).

- ^ a b Stairs, William G. 1998. African exploits: the diaries of William Stairs, 1887–1892, Roy Maclaren, ed., McGill-Queen's University Press, p. 374m 379, ISBN 0773516409.

- ^ a b c d Anonymous. La Grâce du travail: L'imprimerie, la peinture, la chasublerie, filage et tissage, tapis et tentures, la dentelle, la broderie, chez les Franciscaines missionnaires de Marie, Vanves: Impr. franciscaine missionnaire, 1937, p. 9-10, 17.

- ^ a b c Starr, Frederick. 1908. A Bibliography of Congo languages, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p. 25-26, 63.

- ^ a b c Michael Meeuwis. 2009. "Involvement in Language: The Role of the Congregatio Immaculati Cordis Mariae in the History of Lingala", The Catholic Historical Review 95(2): 240-260.

- ^ a b United Nations. Secretary-General. 1996. "Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Resolution 1078 (1996)", http://www.un.org/Docs/s1996993.htm (accessed March 22, 2011).

- ^ a b c Hennessy, Michael A. 2001. "Operation 'Assurance': Planning a multinational force for Rwanda/Zaïre", Canadian Military Journal, Spring 2001, 11-20, http://www.journal.dnd.ca/vo2/no1/doc/11-20-eng.pdf Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 9, 2011).

- ^ a b UN News Service. "Calm in Bunia, transitional government keys to situation in DR of Congo, Annan says", 3 June 2003, http://www.un.org/apps/news/storyAr.asp?NewsID=7294&Cr=DR&Cr1=Congo&Kw1=congo&Kw2=&Kw3=(accessed April 12, 2011). Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b United Nations Security Council. 2010. "Final Report of the Group of Experts on the DRC-Nov 26, 2010", S/2010/596, 29 November 2010, https://www.scribd.com/doc/44370265/Final-Report-of-the-Group-of-Experts-on-the-DRC-Nov-26-2010 (accessed March 24, 2011).

- ^ a b Moore, Jina. 2009. "Hutu rebels drop guns, return to Rwanda", The Christian Science Monitor, 20 February 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b Silcoff, Sean. 1998. "Out of Africa", Canadian Business, Sep 25, 1998, 71(15):18.

- ^ a b Drohan, Madelaine. 2004. "Tango in the Congo", Canadian Geographic, Nov/Dec 2004, 124(6):86-98, http://www.madelainedrohan.com/CongoTango.doc (accessed February 15, 2011)

- ^ a b McNeil, Jr., Donald G. 1998. "Congo exile group emerges to seek ouster of President", The New York Times, 2 September 1998, p. 3, col. 1.

- ^ a b c d Busselen, Tony. 2010. Une histoire populaire du Congo, Brussels: Les Éditions Aden, p. 136, 144-145.

- ^ a b Braeckman, Colette. 2008. "La Gécamines revit grâce à la Chine", Le Soir (Belgium), 1er mars 2008, p. 24, http://archives.lesoir.be/la-gecamines-revit-grace-a-la-chine-l-homme-du_t-20080301-00F30D.html (accessed April 17, 2011).

- ^ a b Anonymous. 2009. [CONGO Le patron de la Gécamines jette l'éponge L'avocat canadien Paul Fortin, PDG de la Gécamines, vient d'annoncer sa démission.], Le Soir (Belgium), 2 octobre 2009, p. 15.

- ^ a b Castonguay, Alec. 2010. "Droits et Démocratie embauche un avocat qui a défendu des criminels de guerre", Le Devoir, 25 septembre 2010, p. A3.

- ^ Wilson, T. Ernest (1967). Angola Beloved. Loizeaux Bros. p. 40. ISBN 9780872139619.

- ^ a b Rotberg, Robert I. (1964). "Plymouth Brethren and the Occupation of Katanga, 1886–1907". The Journal of African History. 5 (2): 285–297. doi:10.1017/S0021853700004849. JSTOR 179873. S2CID 161436189.

- ^ Levine, Allan E. (16 December 2013). "William Grant Stairs". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada.

- ^ de Pont-Jest, René. 1893. "L'Expédition du Katanga, d'après les notes de voyage du marquis Christian de Bonchamps", in: Edouard Charton (editor): Le Tour du Monde magazine, http://collin.francois.free.fr/Le_tour_du_monde/textes/Katenga/katengatexte.htm (accessed March 4, 2011)

- ^ a b Saffery, David. 2007. "Introduction to 2007 edition", in: Joseph A. Moloney. With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–92, London: Jeppestown Press, p. x-xi, ISBN 0955393655.

- ^ Slade, Ruth. 1962. King Leopold's Congo: aspects of the development of race relations in the Congo Independent State, Oxford University Press, p. 134-135, ISBN 9780837159539.

- ^ Carpenter, George Wayland. 1952. Highways for God in Congo: commemorating seventy-five years of Protestant Missions 1878–1953, La Librairie Evangelique au Congo, p. 27.

- ^ Johnson, Hildegard Binder. 1967. "The Location of Christian Missions in Africa The Location of Christian Missions in Africa", Geographical Review, 57(2):168-202.

- ^ Actes de la Congregation Générale des Franciscaines Missionnaires de Marie Tenue à Rome du 2 juin au 24 juin 1911, Vanves près Paris: Imp. Franciscaines missionnaires de Marie, p. 119.

- ^ Anonymous. 1908. "Mère Marie-Bernadette", Annales of the Franciscaines missionnaires de Marie, Tome XXII, juin 1908, p. 192.

- ^ Rade, Paul. 1932. Dans la fôret congolaise, Grande Allée, Québec: Stella Maris, Imprimerie des Franciscaines Missionnaires de Marie, p. 289-290.

- ^ "Fondation Franciscaine au Congo". La semaine religieuse de Québec. Vol. 12, no. 46. [Québec]: D. Gosselin. 7 July 1900. p. 730.

- ^ "Le Congo". La semaine religieuse de Québec. Vol. 13, no. 26 [i.e. 27]. [Québec]: D. Gosselin. 23 February 1901. pp. 424–426.

- ^ a b De Blarer, M -T. 1932. À vol d'oiseau : récits missionnaires : suivis de Comment s'est fondée une mission chez les antropophages [sic], Québec (Province): s.n., Collection Stella Maris, p. 215.

- ^ Wolters, Eug. 1958. "Boeck (De) (Égide) (Mgr.)", in: Biographie Coloniale Belge, Bruxelles: Librairie Falk fils, Vol. V, p. 87-89.

- ^ Storme, M. 1967. "Boeck (De) (Égide)", in: Biographie Coloniale Belge, Bruxelles: Librairie Falk fils, Vol. VI, p. 74-77.

- ^ Bontinck, F. 1988. Les Missionnaires de Scheut au Zaire, 1888–1988, Limete-Kinshasa: Epiphanie, p. 26, 29.

- ^ a b c d Spooner, Kevin A. 2009. "Canada, the Congo crisis, and UN peacekeeping, 1960–64", Vancouver, UBC Press, p. 13-16, 128-130, 224 n.13.

- ^ a b c Bothwell, Robert. 1984. Eldorado, Canada's national uranium company, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p. 107-116, 434.

- ^ a b Rotter, Andrew J. 2008. Hiroshima: The World's Bomb, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 63, 112.

- ^ a b Groves, Leslie R. 1962. Now it can be told: the story of the Manhattan Project, New York, N.Y. : Da Capo Press, [1983] 1962.

- ^ a b Gray, Earle. 1982. The Great Uranium Cartel, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, p. 19-29.

- ^ McNamara, Pat. 2008. "CAO Radioactive waste cleanup in Port Hope, Ontario", Petition: No. 232, Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 4 January 2008, http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/pet_232_e_30304.html (accessed April 19, 2011)

- ^ Eggleston, Wilfred. 1966. Canada's Nuclear Story, London: Harrap Research, p. 44.

- ^ a b Nixon, Alan. Canada's Nuclear Fuel Industry: An Overview, Science and Technology Division, November 1993, Depository Services Program, BP-360E, http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/bp360-e.htm (accessed April 19, 2011).

- ^ Norris, Robert S. 2002. Racing for the bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project's indispensable man, South Royalton, Vt.: Steerforth Press, p. 327.

- ^ Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. "U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946.", President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers. 2. Hiroshima., p. 6 (page 11 of 51), http://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/study_collections/bomb/large/documents/index.php?pagenumber=11 (accessed April 19, 2011).

- ^ Cheek, Dennis W. 2005. "Hiroshima and Nagasaki", in: Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics, Ed. Carl Mitcham, Vol. 2, Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, p.921-924.

- ^ a b Brown, J. C. Gordon. 2000. Blazes along a diplomatic trail: a memoir of four posts in the Canadian foreign service, Victoria, B.C.: Trafford, p. 158, 163, 165, ISBN 1552125246.

- ^ Park, L.C.; Park, F.W. 1962. Anatomy of big business, Toronto: Progress Books, p. 156-158.

- ^ a b Spooner, Kevin A. 2009. "Just West of Neutral: Canadian "Objectivity" and Peacekeeping during the Congo Crisis, 1960–61", Canadian Journal of African Studies, 43(2):303-336.

- ^ a b Granatstein, J.L. 1968. "Canada: Peacekeeper. A survey of Canada's participation in peacekeeping operations", in: Peacekeeping: International Challenge and Response, [Toronto]: The Canadian Institute of International Affairs, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e Gaffen, Fred. 1987. In the Eye of the Storm: A history of Canadian peacekeeping, Toronto: Deneau & Wayne, p. 217-239.

- ^ a b Hillmer, Norman; Granatstein, J.L. 1994. Empire to umpire: Canada and the world to the 1990s, Toronto : Copp Clark Longman, p. 255-256.

- ^ McCullough, Colin. 2011. "Canada, the Congo Crisis, and UN Peacekeeping, 1960–64. Kevin Spooner", review, The Canadian Historical Review, 92(1) (March 2011): 210-212.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo". Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ Zasy Ngisako, Germain. 2001. "Revues des normes camerounaises des inventaires forestiers", Cameroun Ministère de l'Environnement et des Forets and Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'Alimentation et l'Agriculture (FAO), p. 8, footnote 3, http://cameroun-foret.com/system/files/18_61_37.pdf (accessed March 9, 2011). Archived July 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Département de l'Environnement, Conservation de la Nature et Tourisme, Agence Canadienne de Développement International, Inventaire forestier de la cuvette centrale de Zaïre, 1977. Rapport de Blocs préparé par le Gouvernement de la République du Zaïre et la Firme Gauthier, Poulin et Thériault Ltée, Québec, Canada, dans le cadre du programme de coopération de l'ACDI, Québec

- ^ "The Democratic Republic of the Congo", Africa South of the Sahara 2004, Europa Publications, p. 231, ISBN 9781857431834.

- ^ World Resources Institute et le Ministère de l'Environnement, Conservation de la Nature et Tourisme de la République Démocratique du Congo. 2010. Atlas forestier interactif de la République Démocratique du Congo - version 1.0 : Document de synthèse, Washington, D.C.: World Resources Institute., p. 19, http://pdf.wri.org/interactive_forest_atlas_drc_fr.pdf (accessed March 9, 2011).

- ^ Government of Canada. National Defense and the Canadian Forces. "Past Canadian Commitments to United Nations and other Peace Support Operations (as of December 2003)", web page, Date Modified: 2010-04-12, http://www.forces.gc.ca/admpol/past-eng.html (accessed March 9, 2011).[dead link]

- ^ Dewing, Michael; McDonald, Corinne. 2006. "International Deployment of Canadian Forces: Parliament's Role", Government of Canada. Library of Parliament, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, 18 May 2006, http://www2.parl.gc.ca/Content/LOP/ResearchPublications/prb0006-e.htm Archived 2011-03-22 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 8, 2011).

- ^ Lauria, Joe. 1996. "Envoy makes bid to stop killing in Africa", Calgary Herald, November 5, 1996. pg. A.5.

- ^ National Defence and the Canadian Forces. 2008. "Details/Information for Canadian Forces (CF) Operation LEGATION", Chief of Military Personnel, Directorate of History and Heritage, Date Modified: 2008-11-28, http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/od-bdo/di-ri-eng.asp?IntlOpId=181 (accessed March 22, 2011).

- ^ Thompson, Allan. 1996. "Aid allowed into Goma, then halted Guerrilla leader says he will target refugee camp", The Toronto Star, November 12, 1996, p. A.19.

- ^ McGreal, Chris. 1996. "Food farce and fury in Zaire", The Guardian, November 29, 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Morisset, Denis; Coulombe, Claude. 2008. Nous étions invincibles: récit autobiographique : témoignage d'un ex-commando, Chicoutimi: Éditions JCL, p. 151-159.

- ^ Chrétien, Jean. 2007. My Years as Prime Minister, Toronto: Knopf, p. 355-356.

- ^ Fiorilli, Thierry. "300.000? 500.000? 700.000?", Le Soir, Belgium, 22 novembre 1996, p. 8, http://archives.lesoir.be/300-000-500-000-700-000-_t-19961122-Z0CZ3H.html (accessed April 7, 2011).

- ^ Associated Press/Canadian Press. 1996. "Canada ends Zaire operation: Relief mission accomplished, says Baril", The Daily News (Halifax), December 14, 1996, p. 71.

- ^ Braeckman, Colette. 2010. "Récit d'une traque mortelle au Congo", Le Soir, Belgium, 2 octobre 2010, p. 34, http://archives.lesoir.be/recit-d-8217-une-traque-mortelle-au-congo_t-20101002-012XNG.html (accessed April 9, 2011).

- ^ Siddiqui, Haroon. 2003. "Bush doing right thing in sorting out Liberia Africa offers Bush chance to make new start", The Toronto Star, July 6, 2003, p. F01.

- ^ United Nations Security Council. 2003. "In meeting on Democratic Republic of Congo, Security Council hears call for end to impunity for perpetrators of violence", Press Release SC/7810, 7 July 2003, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2003/sc7810.doc.htm (accessed April 12, 2011).

- ^ Jerome, Carole. 2001. "The Unseen Politics of Peacekeeping", in: Future Peacekeeping: A Canadian Perspective, Canadian Strategic Forecast 2001, Toronto: The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies, p. 37-46.

- ^ Heinbecker, Paul. 2010. Getting Back In The Game: A Foreign Policy Playbook for Canada, Toronto: Key Porter Books, p. 94-95.

- ^ United States House of Representatives. 2001. "Statement of Wayne Madsen, author, Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa 1993–1999, Investigative Journalist", Hearing before the Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights of the Committee on International Relations, One Hundred Seventh Congress, First Session, May 17, 2001, http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/intlrel/hfa72638.000/hfa72638_0.HTM (accessed March 31, 2011).

- ^ Martens, Ludo. 2002. Kabila et la révolution congolaise: Panafricanisme ou néocolonialisme?, Anvers: Editions EPO, p. 212-213.

- ^ Mpwate-Ndaume, Georges. 2010. La coopération entre le Congo et les pays capitalistes: un dilemme pour les présidents congolais, 1908–2008, Paris: Harmattan, p. 245-261.

- ^ Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. "Video Interview with Raymond Chrétien", About the Department, http://www.international.gc.ca/history-histoire/video/chretien.aspx (accessed April 10, 2011).

- ^ Schreiner, John. 1997. "State mining chief lets Canada know Congo is open for business, Financial Post, June 25, 1997. pg. 19.

- ^ Campbell, Bonnie. 1999. Canadian Mining Interests and Human Rights in Africa in the Context of Globalization, Section II: Canadian Mining Interests in Africa, January 1999, "Catalogue | Rights & Democracy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-11-17. (accessed April 5, 2011).

- ^ Anonymous. "Demonstrators in Canada protest minister's visit", Agence France-Presse, 12 March 1998.

- ^ a b Freeman, Alan. 2005. "The little fixer from Shawinigan?", The Globe and Mail, Mar 5, 2005, pg. F.3

- ^ Anonymous. "Waging Peace: Democratic Republic of the Congo", Monitoring Elections, The Carter Center, http://www.cartercenter.org/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo-peace.html Archived 2010-11-21 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 22, 2011).

- ^ Clark, Joe. 2006. "A tragedy is now an opportunity", The Globe and Mail, December 6, 2006. pg. A.31.

- ^ Anonymous. "American Barrick Resources Corp (Toronto, Canada) intends to make former Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney an officer of the company; gives him options on 250,000 shares", The Globe and Mail, October 20, 1994, p. B1.

- ^ Barrick Gold Corp. 2011. Annual Report, p. 174

- ^ a b Anonymous. 1996. "American Barrick Steps In", Africa Energy & Mining , N. 175, February 14, 1996.

- ^ a b Anonymous. 1998. "Barrick Steps Back", Africa Energy & Mining, N. 228, May 13, 1998.

- ^ Kennes, Erik. 2005. "The Mining sector in Congo: the victim or the orphan of globalization?", in: Stefaan Marysse and Filip Reyntjens, eds., The Political Economy of the Great Lakes Region in Africa. The Pitfalls of Enforced Democracy and Globalization, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 152-189.

- ^ Newman, Peter C. 2002. "Back in the limelight: Brian Mulroney's crusade to burnish his image and rescue his reputation", National Post, May 11, 2002, pg. B.1.FRO.

- ^ Anonymous. "A Global Mining Powerhouse", Canadian Dimension, Jan/Feb 2011, 45(1):18.

- ^ Congo Basin Forest Fund. CBFF introduction brochure, May 2010, http://www.cbf-fund.org/site_assets/downloads/pdf/Brochure%20mai%202010.pdf(accessed April 5, 2011). Archived February 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Werier, Val. 1994. "Elk Island - a Manitoba paradise", Winnipeg Free Press

- ^ Hawk Uranium. 2009. "Hawk Uranium Appoints Robert S. Stewart as Chief Executive Officer", Press release, Toronto, September 2, 2009, http://sedar.com/DisplayProfile.do?lang=EN&issuerType=03&issuerNo=00013291 (accessed March 15, 2011).

- ^ Franklin Telecommunications Corp. 2000. "Franklin Telecommunications Corp. names Robert S. Stewart CEO; Stewart brings 33 years of global experience in finance/energy/petroleum to Franklin", Business Wire, Press release, 16 September 2000

- ^ Haughton, Jonathan. 1998. "The Reconstruction of a War-Torn Economy: The Next Steps in the Democratic Republic of Congo", Technical Paper, Harvard Institute for International Development, July 1998, p. 9, http://www.grandslacs.net/doc/1221.pdf (accessed March 15, 2011).

- ^ Block, Robert. 2010. "Congo to appeal for emergency aid to help stabilize its decayed economy", The Wall Street Journal, 1 December 1997, p. A16

- ^ Duke, Lynne. 1997. "Congo seeks to improve rights image; Much-needed global aid tied to democratization", Washington Post, 11 December 1997, p. A.29.

- ^ Collins, Carol J.L. 1998. "Congo/Ex-Zaire: Through the Looking Glass", Review of African Political Economy, 25(75):112-123.

- ^ Adastra Minerals Inc. 2005. Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(D) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. For the fiscal year ended October 31, 2004, Sedar file name: Annual report on Form 20-F - English, Jan 31 2005, p. 11, http://www.sedar.com/DisplayCompanyDocuments.do?lang=EN&issuerNo=00001891 (accessed March 15, 2011).

- ^ Coplan, Stephen. 1998. "AMF executive in Congo talks", American Metal Market, 6 February 1998, 106(24):2

- ^ Biminay, Jean-Pierre. "Coup d'État annoncé contre Kabila", http://www.congonline.com/Forum/Bimina13.htm Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 15, 2011).