Buddhism in Greece

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Western Buddhism |

|---|

|

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 25 thousand (0.8%)[1][2] | |

| Religions | |

| Buddhism (Mainly Theravada) | |

| Scriptures | |

| Pali Canon | |

| Languages | |

| Greek and other languages |

Buddhism has existed in Greece since antiquity.[3] Today, there is a sizable Buddhist community in Greece, comprising immigrants and native Greek converts. Buddhism has influenced Greek literary tradition to some extent, as evident in the works of Nikos Kazantzakis.[4]

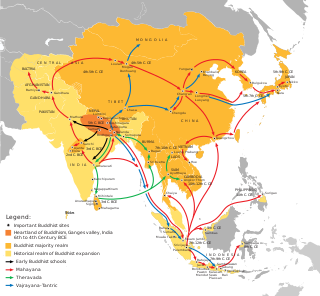

History[edit]

Buddhism and Greek culture share a history of more than 2,000 years. Greek was one of the first languages in which part of the Buddha’s teachings was recorded, long before the Pali Canon Again, in the famous columns and inscriptions of the Indian Emperor Ashoka. Greeks were the first Europeans to embrace Buddhism centuries before the advent of Christianity, and there is strong evidence that the first sculptors to depict the Buddha in the form of statues were of Greek descent. Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greeks, leading to the Greco-Buddhist cultural syncretism. The arts of the Indian sub-continent were also quite affected by Hellenistic art during and after these interactions. (Hellenistic influence on Indian art). The iconography of Vajrapani is clearly that of the hero Heracles, with varying degrees of hybridization.[6]

Menander I was one of the patrons of Buddhism. He was also the subject of the Milinda Panha.

Mahadharmaraksita was a Greek Buddhist master, who according to Mahāvaṃsa traveled to Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka together with 30,000 Greek Buddhist monks from Alexandria of the Caucasus.[7] In addition, Mahāvaṃsa mention how early Buddhists from Sri Lanka went to Alexandria of the Caucasus to learn Buddhism.[7]

The Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka, which are among the Ashoka's Major Rock Edicts of the Indian Emperor Ashoka were written in the Greek language. In addition, the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription was written in Greek and Aramaic. Ashoka used the word "eusebeia" (piety) as a Greek translation for the central Buddhist and Hindu concept of "dharma" in the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription.[8]

Ptolemy II Philadelphus is also mentioned in the Edicts of Ashoka as a recipient of the Buddhist proselytism of Ashoka:

Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-Servant-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. And it [conquest by Dhamma] has been won here, on the borders, even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni. Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika)

Buddhist gravestones decorated with depictions of the dharma wheel have even been found in Alexandria, indicating the presence of Buddhists in Ptolemaic Egypt.[9]

Buddhist manuscripts in cursive Greek, dated later than the second century AD, have been found in modern-day Afghanistan. Some mention the "Lokesvararaja Buddha" (λωγοασφαροραζοβοδδο).[10]

Artistic influences[edit]

Numerous works of Greco-Buddhist art display the intermixing of Greek and Buddhist influences in such creation centers as Gandhara. The subject matter of Gandharan art was definitely Buddhist, while most motifs were of Western Asiatic or Hellenistic origin.

Anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha[edit]

Although there is still some debate, the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha himself are often considered a result of the Greco-Buddhist interaction. Before this innovation, Buddhist art was "aniconic": the Buddha was only represented through his symbols (an empty throne, the Bodhi Tree, Buddha footprints, the Dharmachakra).

This reluctance towards anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha, and the sophisticated development of aniconic symbols to avoid it (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear), seem to be connected to one of the Buddha's sayings reported in the Digha Nikaya that discouraged representations of himself after the extinction of his body.[11]

Probably not feeling bound by these restrictions, and because of "their cult of form, the Greeks were the first to attempt a sculptural representation of the Buddha".[12] In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks did develop syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions: a well-known example is Serapis, introduced by Ptolemy I Soter in Egypt, who combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian Gods. In India as well, it was only natural for the Greeks to create a single common divinity by combining the image of a Greek god-king (Apollo, or possibly the deified founder of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, Demetrius I of Bactria), with the traditional physical characteristics of the Buddha.

Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: himation, the contrapposto stance of the upright figures, such as the first–second century Gandhara standing Buddhas, the stylized curly hair and ushnisha apparently derived from the style of the Apollo Belvedere (330 BC) and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism. A large quantity of sculptures combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography were excavated at the modern site of Hadda, Afghanistan. The curly hair of Buddha is described in the famous list of the physical characteristics of the Buddha in the Buddhist sutras. The hair with curls turning to the right is first described in the Pāli canon; we find the same description in the Dāsāṣṭasāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā.[citation needed]

Greek artists were most probably the authors of these early representations of the Buddha, in particular the standing statues, which display "a realistic treatment of the folds and on some even a hint of modelled volume that characterizes the best Greek work. This is Classical or Hellenistic Greek, not archaizing Greek transmitted by Persia or Bactria, nor distinctively Roman."[14]

The Greek stylistic influence on the representation of the Buddha, through its idealistic realism, also permitted a very accessible, understandable and attractive visualization of the ultimate state of enlightenment described by Buddhism, allowing it to reach a wider audience:

One of the distinguishing features of the Gandharan school of art that emerged in north-west India is that it has been clearly influenced by the naturalism of the Classical Greek style. Thus, while these images still convey the inner peace that results from putting the Buddha's doctrine into practice, they also give us an impression of people who walked and talked, etc. and slept much as we do. I feel this is very important. These figures are inspiring because they do not only depict the goal, but also the sense that people like us can achieve it if we try.

During the following centuries, this anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha defined the canon of Buddhist art, but progressively evolved to incorporate more Indian and Asian elements.

Hellenized Buddhist pantheon[edit]

Several other Buddhist deities may have been influenced by Greek gods. For example, Heracles with a lion-skin, the protector deity of Demetrius I of Bactria, "served as an artistic model for Vajrapani, a protector of the Buddha".[16][17] In Japan, this expression further translated into the wrath-filled and muscular Niō guardian gods of the Buddha, standing today at the entrance of many Buddhist temples.

According to Katsumi Tanabe, professor at Chūō University, Japan, besides Vajrapani, Greek influence also appears in several other gods of the Mahayana pantheon such as the Japanese Fūjin, inspired from the Greek divinity Boreas through the Greco-Buddhist Wardo, or the mother deity Hariti inspired by Tyche.[18]

In addition, forms such as garland-bearing cherubs, vine scrolls, and such semihuman creatures as the centaur and triton, are part of the repertory of Hellenistic art introduced by Greco-Roman artists in the service of the Kushan court.

Scriptures[edit]

Evidence of direct religious interaction between Greek and Buddhist thought during the period include the Milinda Pañha or "Questions of Menander", a Pali-language discourse in the Platonic style held between Menander I and the Arahath Buddhist monk Nagasena.

The Mahavamsa, chapter 29, records that during Menander's reign, a Greek thera (elder monk) named Mahadharmaraksita led 30,000 Buddhist monks from "the Greek city of Alexandria" (possibly Alexandria on the Caucasus, around 150 kilometres (93 mi) north of today's Kabul in Afghanistan), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of a stupa, indicating that Buddhism flourished in Menander's territory and that Greeks took a very active part in it.[19]

Several Buddhist dedications by Greeks in India are recorded, such as that of the Greek meridarch (civil governor of a province) named Theodorus, describing in Kharosthi how he enshrined relics of the Buddha. The inscriptions were found on a vase inside a stupa, dated to the reign of Menander or one of his successors in the 1st century BC.[20] Finally, Buddhist tradition recognizes Menander as one of the great benefactors of the faith, together with Ashoka and Kanishka the Great.

Buddhist manuscripts in cursive Greek have been found in Afghanistan, praising various Buddhas and including mentions of the Mahayana figure of "Lokesvararaja Buddha" (λωγοασφαροραζοβοδδο). These manuscripts have been dated later than the 2nd century AD.[21]

Present day[edit]

There are many Buddhist centers in Greece, four centers founded by the Diamond Way and other centers in cities such as Athens, Thessaloniki, Sparta and Rhodes. The Athens Diamond Way Buddhist Center was founded in 1975 when Lama Ole Nydahl visited Athens for the first time.[22] There are also Buddhist retreats in Corinth and on Mount Olympus, and nine stupas.[23]

Gallery[edit]

- Γανδάρα Βούδας, 1ος-2ος αιώνας

Bibliography[edit]

- Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, 2nd edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity by John Boardman (Princeton University Press, 1994) ISBN 0-691-03680-2

- The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies by Thomas McEvilley (Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts, 2002) ISBN 1-58115-203-5

- Old World Encounters: Cross-cultural contacts and exchanges in pre-modern times by Jerry H.Bentley (Oxford University Press, 1993) ISBN 0-19-507639-7

- Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan (NHK and Tokyo National Museum, 2003)

- Living Zen by Robert Linssen (Grove Press New York, 1958) ISBN 0-8021-3136-0

- Echoes of Alexander the Great: Silk route portraits from Gandhara by Marian Wenzel, with a foreword by the Dalai Lama (Eklisa Anstalt, 2000) ISBN 1-58886-014-0

- "When the Greeks Converted the Buddha: Asymmetrical Transfers of Knowledge in Indo-Greek Cultures" by Georgios T. Halkias, In Trade and Religions: Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange between East and West, ed. Volker Rabens. Brill Publishers, 2013: 65-115.

- The Edicts of King Asoka: An English Rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika (The Wheel Publication No. 386/387) ISBN 955-24-0104-6

- Mahayana Buddhism, The Doctrinal Foundations, Paul Williams, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-02537-0

- The Greeks in Bactria and India, W.W. Tarn, South Asia Books, ISBN 81-215-0220-9

- “The shape of ancient thought. Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian philosophies”, by Thomas Mc Evilly (Allworth Press, New York 2002) ISBN 1-58115-203-5

- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1982. ISBN 9780870993008.

- Ihsan Ali and Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Gandharan Sculptures in Peshawar Museum, Hazara University, Mansehra.

- Alfred Foucher, 1865-1952; Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, L'art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhâra : étude sur les origines de l'influence classique dans l'art bouddhique de l'Inde et de l'Extrême-Orient (1905), Paris : E. Leroux.

See also[edit]

- Kalachakra Stupa (Greece)

- Greco-Buddhism

- Greco-Buddhist monasticism

- Greco-Buddhist Art

- Milinda Panha

- List of Buddhists

- Buddhism in Europe

- Buddhism in the West

References[edit]

- ^ Gaibandha, দৈনিক গাইবান্ধা :: Dainik. "হাজারো বছরের সাক্ষী পার্থেনন". Dainik Gaibandha. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ Times, The Dhaka. "প্রাচীনকালে গ্রীস ও রোমের ধর্ম কেমন ছিল? - The Dhaka Times". Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ "Greco-Buddhism". Theravada. Retrieved 2022-07-13.

- ^ "Ohio State University: Heroic Nihilism: Buddhism in the Work of Nikos Kazantzakis. Thesis submission by Kui Qiu, 1992". Archived from the original on 2022-07-16. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Herakles/Vajrapani, the companion of Buddha

- ^ a b Greco-Buddhism: The Unknown Influence of the Greeks

- ^ Hacker, Paul. Dharma in Hinduism, Journal of Indian Philosophy, 2006, 34:479-496

- ^ The Greeks in Bactria and India, W.W. Tarn, South Asia Books, ISBN 81-215-0220-9

- ^ The Greco Indian Kingdoms, Dr. Uday Dokras

- ^ "Due to the statement of the Master in the Dighanikaya disfavouring his representation in human form after the extinction of body, reluctance prevailed for some time". Also "Hinayanis opposed image worship of the Master due to canonical restrictions". R.C. Sharma, in "The Art of Mathura, India", Tokyo National Museum 2002, p.11

- ^ Linssen; Robert (1958). Living Zen. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 206.

- ^ "The Buddha accompanied by Vajrapani, who has the characteristics of the Greek Heracles" Description of the same image on the cover page in Stoneman, Richard (8 June 2021). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-691-21747-5. Also "Herakles found an independent life in India in the guise of Vajrapani, the bearded, club-wielding companion of the Buddha" in Stoneman, Richard (8 June 2021). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-691-21747-5.

- ^ Boardman p. 126

- ^ 14th Dalai Lama, foreword to "Echoes of Alexander the Great", 2000.

- ^ Foltz (2010). Religions of the Silk Road. p. 44.

- ^ See Images of the Herakles-influenced Vajrapani: "Image 1". Archived from the original on December 16, 2013, "Image 2". Archived from the original on March 13, 2004.

- ^ Tanabe, Katsumi (2003). Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural Contact from Greece to Japan. Tokyo: NHK Puromōshon and Tokyo National Museum. OCLC 937316326.

- ^ Thomas McEvilley (7 February 2012). The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Constable & Robinson. pp. 558–. ISBN 978-1-58115-933-2.

- ^ Tarn, William Woodthorpe (24 June 2010). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-1-108-00941-6.

- ^ Nicholas Sims-Williams, "A Bactrian Buddhist Manuscript"

- ^ "Athens Acropolis Diamond Way Buddhist Center". The 17th Karmapa: Official website of Thaye Dorje, His Holiness the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ Lowenstein, Tom (1996). The vision of the Buddha. Duncan Baird Publishers. ISBN 1-903296-91-9.

External links[edit]

- Theravada Buddhist Center in Greece

- Diamond Way Buddhism in Greece

- UNESCO: Threatened Greco-Buddhist art

- ‘’The Questions of King Milinda’’ translated by Thomas William Rhys Davids.

- The Debate of King Milinda, Most Recent HTML and PDF Editions.

- Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan (Japanese)

- The Hellenistic age

- The Kanishka Buddhist coins

- Interim period: Mathura as the Vaishnava-Buddhist seat of culture and learning