Battle of Kaliabor

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Battle of Kaliabor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mir Jumla's invasion of Assam | |||||||

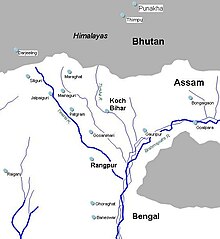

Assam and the river flowing through it | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 700-800 Ships | 30,000 Foot soldiers 12,000 Cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 300-400 Ships captured 21.000 Soldiers taken as prisoners 300 vessels captured | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Kaliabor, also known as Battle of Kaliabar, marked a pivotal naval military confrontation between the Mughal Empire, under the command of its general Mir Jumla II, and the Ahom dynasty, led by Bargohain, on March 3, 1662, near the location known as Kaliabor, situated in modern-day Assam.

During the Mughal war of succession, the Ahoms seized the opportunity to invade the Mughal territory of Kamrup. After Aurangzeb ascended to the Mughal throne, he appointed one of his generals, Mir Jumla II who had aided him in the war as the Governor of Bengal. Subsequently, he dispatched this general to launch a campaign against the Ahom dynasty of Assam in order to reclaim lost territories. As the Mughal forces advanced towards the Ahom capital, they encountered an attack from the Ahoms near Kaliabar, where the Ahoms were numerically superior to the Mughals. Despite the numerical disadvantage, the Mughals emerged victorious, capturing a significant number of Ahoms as prisoners of war.

Background[edit]

In the northeast of the Mughal Empire, Bengal's expanding export economy and the presence of Muslim settlers created a potential area for aggressive military campaigns. The Mughal control remained relatively weak in this region. When Shah Shuja's governorship of Bengal was disrupted by the succession war due to the death of Shah Jahan, local landlords like Prem Narayan, the ruler of Kuch Bihar, rebelled. Concurrently, Jayadhwaj Sinha, the Ahom king, dispatched an army to invade and annex Kamrup, the Mughal border district along the Brahmaputra River.[1]

After being defeated by Aurangzeb, Shah Shuja sought refuge in Arakan. In acknowledgment of Mir Jumla's commendable service over the past sixteen months despite facing numerous challenges, Aurangzeb decided to appoint him as the permanent Governor of Bengal.[2] In mid-1660, Aurangzeb, determined to re-establish control over the northeast region, appointed Muhammad Said Mir Jumla, his ally from the Deccan, as the governor of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. During his initial year in office, Mir Jumla overhauled the provincial administration, revived revenue collection, and effectively enforced Mughal authority across all three regions. He relocated the provincial capital from Rajmahal to Dhaka, aligning with the eastward shift in Bengal's population and economy. Additionally, he made significant investments in various trading ventures, collaborating with both his own agents and European trading companies.[3]

Initially, Mir Jumla annexed Kuch Bihar to the Mughal Empire, demonstrating both vigor and conciliation in his administration. He ordered the call to prayer, known as azan, to be recited from the royal palace terrace. War materials captured were confiscated for the imperial government and sent to Dhaka. Some goods belonging to the King of Koch Bihar were reviewed by Muhammad Abid, the escheat officer. The name Kuch Bihar was changed to Alamgirnagar. Until the appointment of Askar Khan as the permanent faujdar by the Emperor, upon the General's recommendation, Isfandiyar Beg (now titled Khan), son of Allah Yar Khan, served as the acting faujdar of the region. He was supported by Qazi Samui Shujai as diwan and Mir Abdur Razzaq and Khwajah Kish or Das Mansabdar as amirs.[4]

Similar to the Bhuiyas of Bengal, the Maghs, and the Feringhis, the Ahoms posed a significant threat to the security of the Mughals in Bengal, particularly along the northeastern frontier.[5] By November 1661, Mir Jumla was ready to embark on a campaign described as "a holy war with the infidels of Assam," as reported by his official news correspondent.[6]

Preparations and initial conflicts[edit]

The Ahom forces[edit]

The exact number of war-boats possessed by the Ahoms remains uncertain. The historian Fathiya suggests a remarkably high figure exceeding 32,000. Whereas Talish mentions estimates derived from reports of the "Waqiahnavis" of Gauhati, indicating that by 1662, no fewer than 32,000 boats had arrived. Considering those engaged for the army and those belonging to the Assamese, it is plausible that more than half belonged to the Assamese. It's reasonable to estimate that the Ahoms deployed around 1000 war-boats against Mir Jumla, outnumbering his naval strength by more than threefold. However, little is known about the naval organization of the Ahoms and the personnel of such a large flotilla. Only a few Ahom officers' names are recorded, such as the Naubaicha, who oversaw 1000 men for manning royal boats, and the Nausalia Phukan, tasked with one thousand carpenters for boat construction and repair.[7]

According to Wade, the Ahom mariners lacked proficiency compared to the Mughals when navigating the open sea. They also lacked the essential skills for artillery use. Additionally, bridges over rivers were occasionally built by workers brought in from Bengal, as the local population lacked the required expertise.[8]

The Ahom naval soldiers mostly use bows, and arrows and matchlocks but do not come up in courage to the Muhammadan soldiers .

— Padshahnama, [8]

The Mughal forces[edit]

The Mughal governor Mir Jumla gathered a formidable force consisting of 12,000 cavalry, 30,000 foot soldiers, and a flotilla comprising several hundred-armed vessels. Among these vessels were ten ghurabs, or floating batteries, each carrying fourteen guns and towed by four rowing boats. Additionally, the son of the King of Koch Bihar, recently converted to Islam, allied with the Mughals in their campaign against the Ahoms.[6]

Capturing Ahom forts[edit]

The Mughals advanced towards Gharaghat on the right bank of the Karatoya river and reached the Brahmaputra five days later. The army and fleet were instructed to march in close coordination. Dilir Khan led the vanguard, Mir Murtaza was responsible for communication, and the fleet was commanded by admiral Ibn Husain, with assistance from subordinate admirals Jamal Khan and Manawar Khan. Successively, forts of the Ahoms fell into the hands of the Mughals. Strategic posts like Jogigopa at the mouth of the Manas river (opposite Goalpara), Saraighat at the mouth of Bar Nadi, and Pandu and Kajali at the mouth of the Kallang river were evacuated by the Ahoms. Despite the strength and number parity between the Ahom and Mughal fleets, the Ahom fleet did not engage with the imperial fleet until it reached Kajali, which appears peculiar.[9]

The Battle[edit]

The Mughal army reached a location called Kaliabar in the Nowgong district, where a significant naval battle took place on March 3, 1662. Due to the presence of hills along the Brahmaputra River from this point onward, the imperial army had to move away from the riverbank, becoming disconnected from their fleet. This temporary separation of the invading army from the navy provided the Ahoms with the opportunity they desired to launch a vigorous attack. The isolation of the Mughal fleet, coupled with the accidental absence of its admiral Ibn Husain (along with some ships) from the main fleet, emboldened the Ahoms to destroy the imperial fleet.[10]

On the night of March 3, 1662, as the imperial fleet had recently anchored above Kaliabar, an Ahom armada of 700-800 ships under the command of its admiral Bargohain launched a sudden and vigorous assault on the Mughal fleet. Glanius reports that the enemy's fleet consisted of 600 ships.[11] Meanwhile, upon hearing the night-long cannonade, Mir Jumla dispatched Muhammad Mumin Beg Ekkataz Khan to assist the beleaguered fleet, particularly the English, Dutch, and Portuguese ships in the Mughal army, which were erroneously reported by a Moorish informer to have been lost. Due to the lack of habitable areas, unstable ground, dense jungles, and muddy terrain, Muhammad Mumin was unable to reach the fleet during the night. However, he arrived early the next morning accompanied by 10 or 12 horsemen and ordered the trumpets to be blown.[12]

This turn of events decisively determined the outcome of the stubborn contest. Encouraged by Muhammad Mumin's arrival, the Mughals intensified their efforts, while the demoralized Ahoms fled, some by boat and others on land. The Mughals captured around 300 or 400 ships, each armed with "big guns," in addition to powder and lead. Since even the smallest ship accommodated 70 men, it is estimated that at least 21,000 men were taken as prisoners of war.[13] Many were slain by the pursuing Mughal columns, who were instructed not to show mercy. The 50 Ahoms who managed to escape were sentenced by their king to undergo severe punishment. Although the Ahom admiral was captured despite his disguise, he was released at the request of some of Mir Jumla's senior officers. The remaining 300 Ahom vessels anchored about a mile away from Mir Jumla's camp, where they were sunk the following day by artillery fire. Those that fled to the other bank were pursued and some were captured. The effectiveness of the Assamese navy was completely annihilated as a result. This was the most decisive victory of Mir Jumla along his campaign against Ahoms.[14]

The reasons behind the Ahom navy's defeat are evident. Despite their overwhelming numerical superiority and the advantage of the upstream current, they failed to capitalize on these factors. While it initially seemed that the Mughal fleet would be overwhelmed by the sheer force of the Ahom fleet, the heavy Ahom "bacharis" manned by 60 or 70 men each were less maneuverable compared to the lighter and swifter Mughal "kosas." Additionally, the Ahom cannons, although planted on their boats, were smaller and had limited range, as demonstrated by their inability to significantly damage the Mughal boats even at close range. The failure of the Ahom fleet to capture the hard-pressed Dutch vessels, which were temporarily separated from the main Mughal fleet, highlights the ineffectiveness of the Ahom navy. However, the close cooperation between the Mughal and European admirals, along with their determined fighting, enabled the Mughal fleet to withstand the crisis. The timely dispatch of Muhammad Mumin Beg by Mir Jumla to assist the imperiled imperial fleet ultimately tipped the scales in favor of the Mughals.[15]

Aftermath[edit]

By March 1662, the Mughal army proceeded inland, leaving the fleet behind, aiming to capture Garghaon, the capital from which the Ahom ruler and his court had fled. The spoils of war were substantial, including treasure, stored rice, weapons, and armed riverboats. With the onset of the rainy season, Mir Jumla stationed his forces near the capital, while the Ahoms severed the line of Mughal outposts leading back to the Brahmaputra fleet. From May to October, the Mughal army in the capital and the river fleet at Lakhau endured famine, disease, continuous Ahom assaults, and desertions.[16]

As the rains ceased and supplies and reinforcements arrived, the Mughal army was able to confront the Ahoms once more. Ultimately, in early 1663, the Swargadeo (Heavenly King) and his nobles sought peace. The Ahom ruler agreed to become a Mughal vassal, send a daughter with a dowry for marriage to the imperial court, surrender significant treasure and elephants, and cede extensive territories in Darrang and western districts. Mir Jumla began organizing a phased withdrawal and the administration of the newly acquired districts, but he fell seriously ill and passed away in March 1663.[16]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Richards 1993, p. 165.

- ^ Sarkar 1951, p. 208.

- ^ Richards 1993, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Roy 1972, p. 228.

- ^ Roy 1972, p. 112.

- ^ a b Richards 1993, p. 167.

- ^ Roy 1972, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b Roy 1972, p. 114.

- ^ Roy 1972, pp. 118–117.

- ^ Sarkar 1951, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Roy 1972, p. 118.

- ^ Sarkar 1951, p. 239.

- ^ Roy 1972, p. 120.

- ^ Sarkar 1951, p. 240.

- ^ Roy 1972, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Richards 1993, pp. 167–168.

Sources[edit]

- Roy, Atul Chandra (1972). A History of Mughal Navy and Naval Warfares. World Press.

- Sarkar, Jagadish Narayan (1951). The Life of Mir Jumla, the General of Aurangzab. Thacker, Spink.

- Chatterjee, Anjali (1967). Bengal in the Reign of Aurangzib, 1658-1707. Progressive Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8426-1193-0.

- Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.