Bach House (Eisenach)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Bachhaus Eisenach | |

Bachhaus Eisenach, 2020 | |

| |

| Established | May 27, 1907 |

|---|---|

| Location | Frauenplan 21, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany |

| Coordinates | 50°58′17.37″N 10°19′21.4″E / 50.9714917°N 10.322611°E |

| Type | Music museum, biographical museum, memorial site |

| Visitors | 60,057 (2016) |

| Director | Jörg Hansen |

| Owner | Neue Bachgesellschaft e.V., Leipzig |

| Website | www |

The Bach House in Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany, is a museum dedicated to the composer Johann Sebastian Bach who was born in the city. On its 600 m2 it displays around 250 original exhibits, among them a Bach music autograph. The core of the building complex is a half-timbered house, ca. 550 years old, which was mistakenly identified as Bach's birth house in the middle of the 19th century. In 1905, the Leipzig-based Neue Bachgesellschaft acquired the building. In 1907, it was opened as the first Bach museum.

History[edit]

The Bach family was a widespread musical family, with members working in musical professions throughout Thuringia since the first half of the 16th century until the end of the 18th century. Already in 1665, Johann Christoph Bach was appointed organist at St. George's in Eisenach.

Bach's father Johann Ambrosius Bach accepted a position as the Eisenach council's Haußmann (city music director) in 1671. The family first rented rooms in a half-timbered house in the Rittergasse 11 (directly south of today's museum garden), and owned at the time by the city's forests administrator Balthasar Schneider. Since only property owners could claim citizenship, in 1674 Johann Ambrosius Bach bought a house in the Fleischgass (probably Lutherstraße 35), its location was 100 metres to the north of today's museum.[1] The original house in the Fleischgass is no longer standing, it was replaced twice over in the 18th and 19th centuries.[2] Identifying today the exact location of Bach's birth is almost hopeless since people wishing to become citizens did not always move into the places they acquired for that purpose, and instead rented them out.[3] Based on the location of Ambrosius Bach's first rooms at the building in the Rittergasse and his ownership of the property in the Lutherstraße, one may conjecture that Bach's family lived in this area of the city and so at least very close to the location of the present-day museum.[4]

Johann Sebastian Bach was born on 21[5] March 1685 in Eisenach and baptized two days later in St. George's Church. He spent the first 10 years of his life at Eisenach. The family's musical tradition brought him into close contact with music and the musical profession. His father early taught him to play string and wind instruments.[6] At St. George's, Bach could witness his cousin Johann Christoph Bach playing the organ, later his favourite instrument.[7] From 1692 until 1695, Johann Sebastian Bach attended the Latin school at Eisenach and joined its chorus musicus; for its members music lessons were included in the school's timetable on four days of the week.[8] On 1 May 1694, Bach's mother Elisabeth Bach died, on 20 February 1695 also Bach's father Ambrosius died. In July 1695, Johann Sebastian and his brother Johann Jacob left Eisenach to live with the family of their older brother Johann Christoph in Ohrdruf.[9]

1456 to 1800[edit]

The historical Bach House is one of the oldest residential buildings in Eisenach. It originally consisted of two buildings, of which the eastern part was built in 1456 and the western part in 1458. At around 1611, both were joined.[10] As was normal with the Ackerbürgerhäuser (burghers' houses) of that time, the ground floor was used for agricultural purposes: today's instrument hall may have been used as a barn, and the rooms next to the stairs for cattle and horses.[11] In the museum, a cowbell from 1688 found in the Bach House garden reminds of this past. In the first floor of the building, a Renaissance glass window frame and the timber panelling of the living room now decorated as Composing Studio still bear witness of the citizen status of the house's former occupants. At the time of Bach's birth it was owned by Heinrich Börstelmann, headmaster of the Latin School. In 1746, the family of Caroline Amalie Rausch née Bach moved into the building and lived there until 1779. Caroline Amalie was the daughter of Bach's second cousin and friend Johann Bernhard Bach and sister to Johann Ernst Bach, a student of Bach at Leipzig and then court music director at Eisenach.[12]

19th century[edit]

In the wake of the 19th century's Bach renaissance instigated by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and Robert Schumann, among others, devotees went on a search for memorabilia and also for the birthplace of the composer. In 1857, the Bach biographer Karl Hermann Bitter interviewed the still living descendants of Johann Bernhard Bach and determined that Bach was born at the house Frauenplan 21, subsequently called Bachhaus (Bach House).[13] In 1868, the local music society dedicated the memorial plate above the front entrance, thus publicly marking the place as Bach's birthplace.[14] Since then, however, no further evidence in support of this claim has surfaced. An error in the local oral tradition which Bitter encountered can perhaps be attributed to the fact that members of the Bach family did indeed live in this house once, but only at a time long after Bach's birth.

20th century[edit]

When the Leipzig-based Bach-Gesellschaft, founded by Robert Schumann and others in 1850 for the sole purpose of editing all of Bach's works, had completed this task in 1900, its members decided it should be reconstituted as Neue Bachgesellschaft (New Bach Society) to now further the popularity and practice of Bach's music. Three 'eternal' projects were approved: the annual edition of a Bach-Jahrbuch (Bach yearbook), biannual (today: annual) Bachfeste (Bach festivals), and finally the founding of a Bach museum. As the desired location of the society's museum the School of St. Thomas at Leipzig was chosen, where Bach had lived with his family and served as cantor and music teacher for 27 years. However, the magistrate of Leipzig decided to demolish the building in 1902, thus thwarting the society's plans.[15] Among other relics, the entrance door to Bach's rooms in the school was saved from destruction by its then music teacher Bernhard Friedrich Richter, son of the former Thomaskantor Ernst Friedrich Richter, and was later dedicated to the Bach House.[16] Today, this door prominently marks the start of the exhibition within the museum.

When news reached the society's members that Bach's (still undisputed) birth house at Eisenach was also under threat by demolition plans, the New Bach Society decided to acquire the building on May 15, 1905, and to open the world's first Bach museum at this site. Among the supporters of this project were the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, the composer and violinist Joseph Joachim, the Cantor of St Thomas Gustav Schreck, the director of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin Georg Schumann, and the Leipzig music publishers Breitkopf & Härtel and C.F. Peters.[17] The Bach House was formally opened on 27 May 1907. The choir of St. Thomas, Leipzig under Cantor of St. Thomas, Gustav Schreck, and the Weimar Hofkapelle conducted by Georg Schumann, sang and played.[18]

In 1928, when the Eisenach hobby historian Fritz Rollberg undertook a research into the city's tax records and discovered that Johann Ambrosius Bach had paid taxes from 1674 until his death in 1695 for a different building in Eisenach, the Bach House was long established as a Bach memorial site throughout the world.[19] When the house underwent complete restoration in 1972–1973, the memorial plate from 1868 was taken down and went into storage. Since visitors kept believing to be visiting Bach's birthplace even without the plate, it was decided in 2007 to restore it as an essential part of the building's history. Today, the historical error is explained in the museum, where one of the tax files discovered by Rollberg is on display.

An air raid on 23 November 1944 and artillery fire by the approaching U.S. troops in the night of 5 April 1945 caused substantial damage to the roof of the Bach House in particular.[20] On 29 April 1945, the U.S. commander of the city, Lt. Col. Knut Hansston, ordered the museum to be repaired immediately, and one year later, on 22 June 1946, the Soviet Military Administration ordered the Johann Sebastian Bach museums in Arnstadt and Eisenach to be re-opened and confirmed the appointment of Bach House Director Conrad Freyse to the post in which he had been working since 1923.[21]

Already in 1911, the museum had expanded into the adjacent building Frauenplan 19.[22] In 1973, the buildings underwent a complete restoration and the exhibition was newly designed with financial aid by the East German (GDR) government.[23] The museum now also included the building Frauenplan 21a to the west of the Bach House.[24] Since the museum's owner was still the New Bach Society, now an international society with over 3,000 members in both parts of politically divided Germany (and throughout West and East Europe, and also in the U.S.), the Bach House – unlike the Leipzig Bach-Archiv – was never incorporated into the GDR's national combine Nationale Forschungs- und Gedenkstätten Johann Sebastian Bach der DDR.[25] Rising visitor numbers (over 130,000 in some years) and the imminent Bach year of 1985 led to a further expansion of the museum into the building Frauenplan 23 further west of the Bach House in 1980.[26]

21st century[edit]

From 2005 to 2007, the buildings to the west of the Bach House were replaced by a new museum building, the historical building again underwent restoration, and the exhibition was completely modernized. The project was financed by the Free State of Thuringia, the government of the Federal Republic of Germany and the European Union, with a grant totalling 4.3 mio. Euros.[27] Earlier, the New Bach Society had purchased the properties Frauenplan 21a and 23 (which before had only been rented) with donations by its members. A new, smaller building to the back of the Bach House garden had already been put up in 2001, it contains a study hall for school classes and a library. The demolition of the 19th century buildings to the west of the Bach House in 2000 and 2001 was subject of heavy debate among the Eisenach citizens.[28] The same is true for the finally realized new museum building with its modern organic design by architect Prof. Berthold Penkhues from Kassel, Germany, a former student of Frank O. Gehry. Penkhues' design had won first prize among twelve submissions in an architectural design contest to which the New Bach Society had invited in 2002.[29] The new exhibition was designed by Prof. Uwe Brückner, Stuttgart, Germany.[30]

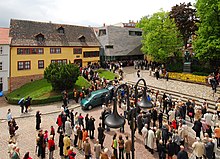

On 17 May 2007, the museum was re-opened at the start of a festival period lasting until 27 May, the day of the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Bach House. At the day of the re-opening, the choir of St. Thomas, Leipzig, inaugurated the new museum building with a concert under Georg Christoph Biller, the Cantor of St. Thomas at the time.[31]

Exhibits, expositions and collections[edit]

Since 2004, there have been the following special expositions at the Bach House:

- 2004: Ich habe fleißig seyn müssen ... – Johann Sebastian Bach and his Eisenach childhood[32]

- 2005: Johann Sebastian Bach – Ansichtssache[33]

- 2007: The Man in the Golden Waistcoat (on Johann Christian Bach)[34]

- 2008: Bach through the Mirror of Medicine[35]

- 2009: Blood and Spirit – Bach, Mendelssohn and their music in the Third Reich[36]

- 2010: Bach's Passions – Between Lutheran tradition and Italian opera[37]

- 2011: Memories of Wanda Landowska[38]

- 2012: Luther and [Bach's] Music[39]

- 2013: Bach & Friends[40]

- 2014: "B+A+C+H = 14": Bach and numbers[41]

- 2015: Bach in Berlin[42]

- 2016: Luther, Bach – and the Jews[43]

- 2017: Text: Luther & Music: Bach[44]

- 2018: Women and Bach's Music[45]

- 2019: Picture Puzzles – on Bach Iconography[46]

Since 2013 the Bach House has been showing its exhibitions also at Berlin Cathedral.[47]

Exhibition rooms in the historical Bach House[edit]

The collection of baroque musical instruments started with a gift of four instruments by the Dutch collector Paul de Wit in 1907, and a gift of 164 instruments by the heirs of musicologist and conductor Aloys Obrist who had killed both himself and his former lover, the opera singer Anna Sutter, in 1910.[48] String instruments of the collection include a viola da gamba with seven strings, built by Bach's Leipzig friend and collaborator Johann Christian Hoffmann in 1725,[49] a violoncello piccolo with five strings (northern Bohemia, ca. 1750)[50] which Bach demanded for nine cantatas and (according to some views) the cello suite BWV 1012, and a viola d'amore with six 6 gut playing strings and 6 metal resonating strings an octave higher (Vienna, around 1700).[51]

Since 1973, five baroque keyboard instruments are demonstrated in a music performance every hour.[52] These include two chamber organs (Switzerland, ca. 1750,[53] and Thuringia, ca. 1650), a fretted clavichord (around 1770),[54] and a spinet built 1765 in Strasbourg by Johann Heinrich Silbermann, a nephew of Gottfried Silbermann whose instruments Bach helped sell in Leipzig.[55] The Thuringian positive organ's history and Bach's biography overlap: from 1714 on, it served as a church organ in Kleinschwabhausen, about 15 km from Weimar where Bach was court organist at the time. Bach's protégée and family friend, the court organ maker Heinrich Nicolaus Trebs, repaired the organ in 1724 and 1740, and Johann Caspar Vogler, Bach's student and successor as court organist, tested the organ in 1738, 1740 and 1744. Since inspecting the dukedom's organs belonged to the court organist's duties, the museum conjectures that Bach must have known and played this instrument, even though there is no record of it.[56]

The exhibits include the so-called Bach spectacles long believed to have been worn by Bach,[57] and the Bach Goblet. It is still an unsolved riddle who may have been the donor of the goblet, and on what occasion Bach received it.[58] Bach's second, much younger wife Anna Magdalena is remembered with an always fresh bouquet of yellow carnations – she was a große Liebhaberin von der Gärtnerey (a great lover of gardening) and these were her favorite flowers.[59] Three rooms in the upper floor of the historical Bach House present historical living quarters (bedroom, living room, kitchen). Their furnishing is virtually unchanged since the rooms were first decorated by the Weimar Court Antiquary in 1906 with local items from around 1700 (including door handles and fittings).[60]

Since 2017 a room in between the historical living quarters and cladded in black hosts the exhibition space Bach's inner world.[61] Presented here is a reconstruction of Bach's theological library, facilitated by the written estate which lists 52 theological book titles bound in 81 volumes as having been privately owned by Bach.[62]

Exhibition in the modern building[edit]

A 2004 painting by Johannes Heisig depicts Bach performing a cantata in the Leipzig Church of St. Thomas with his choir.[63] The history of Bach iconography is treated on the northern wall of the modern building, starting with contemporary paintings, among them the painting of Johann Jacob Ihle which purportedly depicts Bach at around 1720, and a pastel painting which Charles Sanford Terry identified in 1936 as the Bach portrait formerly owned by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach but whose authenticity has since been doubted.[64] Also on display is the early Bach portrait by Gebel[65] which was used for the title page of the first volume of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in 1798/99.[66] Finally there is a 1910 copy of the undoubtedly authentic painting by Elias Gottlob Haussmann, the original can be found in the old town hall in Leipzig. Thirty-nine original prints, arranged in 'families', depict how our picture of Bach has changed through the centuries.[67]

An original Bach autograph, giving the history from its first discovery to its inclusion in the Neue Bach-Ausgabe, is on display. The autograph is the continuo part of the cantata Alles nur nach Gottes Willen, BWV 72. It is, like most hand-written instrumental parts for Bach's cycles of cantatas, a collaborative work: the right hand side of the sheet on display (chorus, recitative) was written by Bach's student and nephew Johann Heinrich Bach (the son of Bach's older brother Johann Christoph Bach from Ohrdruf), the upper left hand side (air) was written by Bach's wife Anna Magdalena Bach, and the music of the final chorale, along with all titles, subtitles, and some corrections up to the word Fine, are in the hand of Johann Sebastian Bach.[68] Another exhibit is the Clavecin Royal (Johann Gottlob Wagner, Dresden 1788).[69]

Library and collections[edit]

To the museum belongs a library which is open to the public during general opening hours. It has about 5,500 volumes, mostly on Bach and his contemporaries, musical instruments, and on musical history in general. Books can be searched by an OPAC.[70]

As the first and – for a long time – only Bach museum, the museum's mandate by the New Bach Society was to "collect everything that concerns Johann Sebastian Bach, his life and works, and his reception."[71] However, when the museum was founded in 1907, this mandate was already quite impossible to fulfill. Eighty percent of all known Bach autographs were (and still are) in the possession of the Berlin State Library,[72] and already at the time, private collectors willing to part with what was left were demanding prices far exceeding the means of a private society.[73] Still, in its early years the following autographs were acquired by the Bach House:[74]

Subsequently, the collection grew by donations, notably those of Oskar von Hase and the Leipzig music publishers C.F. Peters and Breitkopf & Härtel, and by inheritances, like those from Philipp Spitta, Wilhelm Rust, Paul Graf Waldersee, Aloys Obrist, Wilhelm His, and Christoph Trautmann. Apart from the items on display, the following are particularly noteworthy: a Thuringian Harpsichord from 1715,[75] a harpsichord by Jacob Hartmann (ca. 1765),[76] a second spinet by Johann Heinrich Silbermann (1765),[77] and a pedal clavichord (ca. 1815).[78] Additionally three school notebooks by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, a first edition of The Musical Offering (part A) from 1747, the source C of Bach's lost Genealogie der musicalisch-Bachischen Familie (genealogy of the musical Bach family), the only known libretto of the lost Bach wedding cantata Sein Segen fließt daher, wie ein Strom (BWV Anh. 14, Immanuel Tietze, Leipzig 1725), a collection of silhouettes of the Ohrdruf Bach family, letters of 19th century Bach researchers like Karl Hermann Bitter, and documents, measurements and casts relating to the excavation of the (supposed) Bach bones by Wilhelm His and Carl Seffner (including casts of the cranium in plaster and bronze).[79] In 2013, the Bach House acquired 62 of what originally probably had been 152 hand-written choir parts, which the choir sang from when Felix Mendelssohn performed Bach's St Matthew Passion in the Berliner Singakademie on 11 March 1829 for the first time after Bach's death.[80]

Ownership, finances, Blaubuch, museum directors[edit]

All real property and the collections are owned by the New Bach Society. Since 5 July 2001, the museum is managed by the Bachhaus Eisenach gemeinnützige GmbH, a registered charitable company, with the New Bach Society as its sole associate. The supervisory board includes representatives of the New Bach Society, the City of Eisenach, the Lutheran Church, and the government of the Free State of Thuringia. The funding of the museum is subject of a contract between the New Bach Society, the City of Eisenach, and the Free State of Thuringia. The majority of public funds comes from the Thuringian government. Own proceeds from ticket sales, the shop and the café cover two thirds of the museum's annual expenses. Donations go into restorations and acquisitions for the museum's collection.[81]

Since the opening of the Bach House in 1907 there have been the following museum directors:[82]

- Dr. Georg Bornemann, 1907–1918 (assistant: Dr. Albrecht Göhler, brother of composer and conductor Georg Göhler, 1912–1914)

- Ernst Fleischer, 1918–1923

- Conrad Freyse, 1923–1964

- Günther Kraft, 1964–1971

- Ilse Domizlaff, 1971–1990

- Dr. Claus Oefner, 1990–2001

- Dr. Franziska Nentwig, 2002–2005

- Dr. Jörg Hansen, since 2006

Visitor numbers, tourism[edit]

There are about 60,000 visitors to the Bach House per year,[83] making it one of Germany's most frequented music museums and second to the Beethoven House in Bonn.[84]

Bach monument[edit]

The Bach statue in front of the Bach House was the second monument for Johann Sebastian Bach. It was the first to show the composer figuratively in the form of a full statue.[85] It was sculpted by Adolf von Donndorf and cast by Hermann Heinrich Howaldt in Brunswick, Germany. The monument was commissioned in 1878 by the Denkmal-Committee (monument committee) founded by culture loving citizens of Eisenach, among them the city's cantor Carl Müller-Hartung and the writer Fritz Reuter. Clara Schumann, Hans von Bülow, Joseph Joachim and Franz Liszt helped raise the monies by giving beneficial concerts, and the project was also supported by Johannes Brahms. It was unveiled on 28 September 1884 after a concert of Bach's Mass in B minor conducted by Joseph Joachim in St. George's Church. Its first location was on the market place in front of the portal of St. George's. The monument was moved to its present location in front of the Bach House when the Frauenplan was redecorated in 1938.[86] The composer is shown standing, holding a feather quill in his right hand, and leaning with his left on a stack of sheet music carried by an angel. The monument's base was substantially shortened when it was moved. A relief plate depicting Saint Cecilia, the patron of church music, which was originally attached to the base, can now be seen on the stone wall behind the monument.[2]

Light art[edit]

Ingo Bracke, a light artist from Saarbrücken and with his wife Mary-Anne Kyriakou collaborator in the i Light Marina Bay festival in Singapore, created the installation IN VERSUS F: A Score of Light – An Architectural Tune for the Bach House. It was first shown on 13 December 2008, and has been permanently installed since 21 March 2011. Starting at sunset and ending at 11 p.m., it is on display on all Saturday evenings and evenings before public holidays.[87]

Awards[edit]

The exhibition designers Atelier Brückner were awarded a bronze ADC award by the Art Directors Club on 12 April 2008 for the innovative new design of the Bach House permanent exhibit.[88] Marc Tamschick, the director of the multimedia installation walkable composition was awarded a Finalist Diploma at the World Media Festival in Hamburg on 14 May 2008.[89] For the new design of the Bach House permanent exhibition, Atelier Brückner was also awarded a special prize for outstanding scenography by the Association of German Interior Architects BDIA on 24 October 2008.[90]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach, p. 20.

- ^ a b Martin Petzoldt: Bachstätten, p. 68.

- ^ Cf. Domizlaff, Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 128: At the time of Bach's birth, the Bach House was owned by Brunswick-born Heinrich Börstelmann, school director of the Latin school at which Bach was later a pupil. Börstelmann had rented the place out to three parties (but not the Bach family).

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach, p. 20 names the house Lutherstraße 35 as Bach's birthplace.

- ^ The date refers to the Julian calendar still in use at Eisenach then, it is reproduced in almost all biographies, and on 21 March there are traditional festive celebrations and concerts in Bach's memory in places like Eisenach, Weimar, and Leipzig up to this day. The actual date according to the modern, Gregorian calendar is, however, 31 March.

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach, pp. 22, 28.

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach, pp. 25.

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach, pp. 35, 38.

- ^ Jörg Hansen, 100 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 101. For the dendrochronological dating by the University of Bamberg cf. Bachhaus – eines der ältesten Fachwerkhäuser. Nachrichtendienst www.eisenachonline.de, 28 August 2006. Last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 129; Hartmut Ellrich: Bach in Thüringen, p. 55.

- ^ Cf. Karl Hermann Bitter: Johann Sebastian Bach. Wilhelm Baensch, Berlin 1881 (2nd ed.), pp. 49–50: "Auf dem Frauenplan daselbst erhebt sich über einer mit grünem Rasen bekleideten hügelartigen Erhöhung des Bodens ein Haus von bescheidner Ausdehnung und behaglich einladendem Aeusseren. Der Blick gleitet von ihm über den freien Platz hinaus auf die bewaltdeten Höhen, welche sich um die Stadt herumziehen. Ein geräumiger Hausflur, wo in den Zeiten des alten Bürgerthums die Familie sich zu versammeln pflegte, empfängt den Eintretenden. Rechts im Hintergrunde führt eine gewundene Treppe zu der in der halben Höhe des Hauses nach hinten zu belegenen Küche und in das obere Stockwerk des Hauses. Durch die Hinterpforte tritt man unmittelbar in ein freundliches Gärtchen. Kleine niedrige Zimmerdeuten auf die geringeren häuslichen Bedürfnisse früherer Zeiten. Das Ganze des Hauses zeigt, dass seine Bewohner sich einer gewissen Wohlhabenheit erfreut haben mochten." As for Bitter's research in Eisenach cf. Ilse Domizlaff, Das Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 13: "Bei den Vorarbeiten zu seiner 1865 veröffentlichten Bach-Biografie nahm Carl Heinrich Bitter Beziehungen zu den noch lebenden Nachfahren des Johann Bernhard Bach auf, um den Lebensumkreis von Johann Sebastians Kindheit zu erforschen. Er erfuhr die schon lange in Eisenach mündlich verbreitete Überlieferung, daß Johann Sebastian Bach in eben diesem Haus geboren worden sei und beschrieb es in seiner Bach-Biografie in diesem Sinn. Weiter bezog man sich auf eine angeblich verschollene Familienchronik. Spätere Biografen überprüften das Zustandekommen dieser Aussagen nicht und übernahmen sie einfach."

- ^ For the history of the plate cf. Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 12.

- ^ Martin Petzoldt: Bachstätten, S. 67.

- ^ Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus, p. 20, fn. 34.

- ^ Cf. for the plans to demolish the Bach House and its acquisition by the Bach Society Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 16–21. Domizlaff concedes that without the historical error in determining Bach's birthplace, Eisenach's most impressive residential building from the Renaissance era would no longer be standing today.

- ^ Neue Bach-Gesellschaft: Drittes deutsches Bach-Fest zur Einweihung von Johann Sebastian Bachs Geburtshaus als Bach-Museum; Fest- und Programmbuch, Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1907.

- ^ For Rollberg's research and its results cf. Ilse Domizlaff, Das Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 8–9 and 128–132.

- ^ Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus, p. 23; Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 60–61.

- ^ SMA Order No. 289, 13 July 1946, reprinted in Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 67.

- ^ Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 12.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, S. 104.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 106.

- ^ Jörg Hansen, 10 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach gGmbH, pp. 49, 61 (fn. 1).

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: 100 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 104.

- ^ Cf. Bachhausensemble on the website of the Society for the Preservation of Eisenach http://www.fzee.de/scripts/angebote/640? (version of 11 August 2007 via archive.org)

- ^ Bachhaus – Preisträger stehen fest. News service www.eisenachonline.de, 10 March 2003. Accessed 16 November 2011.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: 100 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 106.

- ^ Festwoche 100 Jahre Bachhaus – 17–27 May 2007. News service www.eisenachonline.de, 15 May 2007. Accessed 16 November 2011.

- ^ Franziska Nentwig, Uwe Fischer: Ich habe fleißig seyn müssen. Johann Sebastian Bach und seine Kindheit in Eisenach (Ausstellungskatalog). Bachhaus, Eisenach 2004. ISBN 978-3-932257-03-2

- ^ Franziska Nentwig, Sebastian Köpcke: Johann Sebastian Bach: Ansichtssache. Bachhaus, Eisenach 2005, ISBN 978-3-932257-04-9

- ^ No catalogue. Cf. Volker Blech: Das schwarze Schaf der Bachfamilie, in: Die Welt, 18 August 2007, last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: Bach through the Mirror of Medicine: exhibition catalogue. Bachhaus, Eisenach 2008, ISBN 978-3-932257-05-6. For the exhibition also cf. Jörg Hansen: Bach im Spiegel der Medizin. Sonderausstellung im Bachhaus Eisenach, Thüringer Museumshefte 17, 2008, 1, pp. 73–81; Kate Conelly: Hello, I'm Bach, in: The Guardian, 4 March 2008, last checked 20 September 2012, Eleonore Büning: Die gottgedachte Spur, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 27 February 2008, last checked 16. November 2011.

- ^ Jörg Hansen, Gerald Vogt: Blood and Spirit – Bach, Mendelssohn and their music in the Third Reich (exhibition catalogue). Bachhaus, Eisenach 2009. ISBN 978-3-932257-06-3. For the exhibit also cf. Michael Levitin Rescued from the Nazis, in: Newsweek, 1 June 2009, last checked 20 September 2012, Hans Jürgen Linke: Voller Eifer, voller Zorn, in: Frankfurter Rundschau, 6 May 2009, last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ No catalogue. Cf. Jan Brachmann: Bitte nicht so theatralisch singen, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 June 2010, last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ No catalogue. Cf. Michael White: "The Woman Who Legitimized the Harpsichord", The Daily Telegraph (internet blog), 14 June 2011, accessed 20 September 2012;

Aaron J. Goldman: "'Bach' to the Future With Wanda Landowska", The Jewish Daily Forward, print version 27 May 2011, accessed 20 September 2012;

Tobias Kühn: "Missionarin am Cembalo", Jüdische Allgemeine, 23 June 2011, accessed 16 November 2011. - ^ No catalogue. Cf. Michael Jäger: "Die Welt ist nicht aus den Fugen", Der Freitag, 23 March 2012, accessed 15 September 2012.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: Bach & Friends. Bach's Life in 82 Copperplate Engravings. Bachhaus, Eisenach 2013, ISBN 978-3-932257-07-0.

- ^ No catalogue. Cf. Philipp Oltermann: JS Bach's 329th birthday is red letter day for scholars and numerologists, The Guardian, 6 March 2014, accessed 29 November 2014.

- ^ Cf. Alexander Odefey: Vielerlei Instrumente, eine Hochzeit und ein Opfer für den König In: NZZ, 3 October 2015, accessed on 9 July 2016.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: Luther, Bach – and the Jews, Exhibition Catalogue, Bachhaus, Eisenach 2016, ISBN 978-3-932257-08-7. Cf. Volker Hagedorn: „Sein Blut komme über uns“ In: DIE ZEIT, No. 30/2016, 14 July 2016, p. 47, accessed 29. July 2016; Arno Widmann: War Johann Sebastian Bach ein Antisemit In: Berliner Zeitung, No. 173/2016, 26 July 2016, p. 20, accessed 29 July 2016.

- ^ Cf. Wolfgang Hirsch: Luthers Leistungen als Lieddichter - Sonderausstellung in Eisenach[permanent dead link] In: TLZ, 29 April 2017, accessed 17 May 2017.

- ^ Cf. Wolfgang Hirsch: Sonderausstellung Bachhaus Eisenach: Frauen und Bachs Musik In: TLZ, 28 April 2018, accessed 29 April 2018.

- ^ Cf. Wolfgang Hirsch: Wie hat Johann Sebastian Bach wirklich ausgesehen? In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 7 July 2019, accessed 17 September 2019.

- ^ The exhibitions of the Bach House at Berlin Cathedral regularly take place from the end of the first week of March until the May 1st, which is a public holiday in Germany. Most of these have been previews of later exhibitions at Eisenach. For 2016 siehe „Gehülfin“ oder Cembalo-Amazone: Johann Sebastian Bach und seine Frauen Deutsche Welle, 10 March 2016, accessed 29 July 2016. For 2018 cf. Ganz großes Drama, 31 March 2018, accessed 27 April 2018.

- ^ For a detailed description of the museum's collection of musical instruments see Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 74 no. I 35.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 102 no. I 70.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 80 no. I 42.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 104. For an even earlier tradition cf. Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus, p. 22: "Daß im Bachhaus die Musik nicht schweigen darf, versteht sich von selbst. Unsere Führer sind in der Lage, auf den originalen Tasteninstrumenten vorzuspielen; der historische Klang ist dem Ohr des Besuchers nahezubringen."

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 164-166 no. I 93.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 136 no. I 80.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 127 no. I 75.

- ^ Geburtstag mit Filmpremiere und Orgelweihe. News service www.eisenachonline.de, 9 March 2012. Last checked 15 September 2012. The further history of the instrument is also peculiar: In 1816 it was acquired by the Weimar penitentiary, and on a leaflet attached to the inside of the organ, Johann August Stickel, the jail's director at the time, noted: Die zu dieser Zeit befindlichen Sträflinge, 83 an der Zahl, hat ein jeder zum geringsten 2 Groschen hinzugegeben. (The 83 convicts presently serving here have each contributed 2 Groschens at the very least.) In the 20th century, the organ was in the possession of musicologist Traugott Fedtke, who added an electric motor and a carillon, among other things. In 2009 the organ was acquired by the Bach House at an auction in Traunstein, in the south of Germany, and was subsequently restored. Cf. Thüringer Barockorgel kehrt in die Heimat zurück. News service www.eisenachonline.de, 10 December 2009. Last checked 15 September 2012.

- ^ Cf. Alexander Hiller: "Wem gehörte Bachs Brille?" Bach-Magazin 17, 2011, p. 51.

- ^ According to one theory, the occasion may have been Bach's appointment as Royal Polish Electoral Saxon Court Composer in 1736. Since the musical notes of the poem proceed in a manner called Krebs (crab) in German (each line mirrors the previous line), others assume a lavish gift to Bach's 50th birthday by Bach's most prominent Leipzig student Johann Ludwig Krebs who passed Bach's musical exam on 24 August 1735. Cf. Conrad Freyse: "Die Spender des Bach-Pokals." In: Bach-Jahrbuch 40, 1953, p. 108–118; Eric Chafe: Tonal Allegory in the Vocal Music of J. S. Bach, Oxford: University of California Press, 1991, Ch. 2, p. 27–30.

- ^ Werner Neumann, Hans Joachim Schultze: Bach-Dokumente Band II – Fremdschriftliche und gedruckte Dokumente 1685–1750. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1969, p. 423.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, S. 21.

- ^ Cf. Tilman Krause: Bibeln kann man gar nicht genug haben. In: Die Welt, 27 March 2017, accessend 29 April 2018.

- ^ For a facsimile of the estate and detailed bibliographical information for each title cf. Robin A. Leaver: Bach's theological library, Hänssler, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 978-3-7751-0841-6, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Bachgemälde im Bachhaus. News service www.eisenachonline.de, 22. März 2011. Last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ Charles Sanford Terry: Portraits of Bach. In: Music & Letters 17, 1936, pp. 286–288.

- ^ Emanuel Traugott Goebel (1751–1813) or Johann Emanuel Goebel (1720–1759) are believed to be the painter of the portrait, cf. Ingrid Reißland: Johann Sebastian Bach – Bildnisse und Porträtplastiken im Spiegel der Bach-Ikonographie. In: Reinmar Emans (ed.): Der junge Bach – weil er nicht aufzuhalten, Erfurt: Erste Thüringer Landesausstellung, 2000, pp. 131–155 (144). For the history of the painting also cf. Günther Wagner: Ein unbekanntes Porträt Johann Sebastian Bachs aus dem 18. Jahrhundert? In: Bach-Jahrbuch 81, 1988, pp. 231–233.

- ^ Cf. Peter Uehling: Ein neues Porträt von Johann Sebastian Bach. In: Berliner Zeitung, 6 August 2014, accessed 28 November 2014. Uehling notes that what is on display on the sheet of music in the painting is Bach's name b–a–c–h in (German) musical notation.

- ^ Cf. Werner Neumann: Bilddokumente zur Lebensgeschichte Johann Sebastian Bachs (Bach-Dokumente vol. iv), Bärenreiter, Kassel 1979. ISBN 978-3-7618-0250-2. Gisela Vogt (ed.): Bach-Bildnisse als Widerspiegelung des Bach-Bildes. B. Katzbichler, München 1994. ISBN 978-3-87397-129-5.

- ^ Johann Sebastian Bach: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke, Serie I, Kantaten Band 6, Kritischer Bericht. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1996, p. 66.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach pp. 143–145 no. I 85.

- ^ "Bachhaus, Eisenach - start/welcome". vzlbs2.gbv.de.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: 100 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, p. 103.

- ^ Bach-Sammlung. Website of the Berlin State Library. Last checked 16. November 2011.

- ^ Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, S. 33.

- ^ Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 17, 21.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 132 no. I 78.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 129 no. I 77.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 127 no. I 76.

- ^ Herbert Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach p. 138 no. I 82.

- ^ For these objects cf. Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 17–21. For the cranium casts cf. Jörg Hansen: Bach im Spiegel der Medizin: Ausstellungskatalog, Bachhaus, Eisenach 2008, ISBN 978-3-932257-05-6, p. 18.

- ^ Cf. Volker Blech: Der verschollene Notenschatz von Mendelssohn Bartholdy In: Berliner Morgenpost, 14 February 2013, last checked 21 February 2013.

- ^ Jörg Hansen: 10 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach gGmbH, pp. 51, 60.

- ^ For the time before 1983 cf. Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, also cf. http://www.nmz.de/kiz/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=11447 (Version of 27 September 2007 via archive.org).

- ^ 2010: 62,072 visitors Amerikanische Gäste sorgen für stabile Besucherzahlen. news service www.eisenachonline.de, 5 January 2011, accessed 16 November 2011; 2012: 59,000 visitors Wartburg verliert Besucher, Bachhaus legt etwas zu., in: Thüringer Allgemeine, 10 January 2013, accessed 28 November 2014; 2017: 73,824 visitors Bachhaus beklagt heftigen Einbruch der Besucherzahlen, in: Thüringer Allgemeine, 8 January 2019, accessed 18 September 2019; 2018: 50,251 Bachhaus beklagt heftigen Einbruch der Besucherzahlen, in: Thüringer Allgemeine, 8 January 2019, accessed 18 September 2019.

- ^ Beethoven-Haus, Bonn, 2010: 100,000 visitors (from German Wikipedia's de:Beethoven-Haus); Bach-Museum, Leipzig, 2010: 48,000 visitors and Händel-Haus, Halle, 2010: 34,000 visitors, for the last two numbers cf. the archived links available at this page's German version de:Bachhaus Eisenach, accessed 1 May 2018.

- ^ Quoted from the museum texts. The first Bach monument was sponsored in 1843 by Felix Mendelssohn and stands in Leipzig in a small park behind the Church of St. Thomas; it is not to be confused with Carl Seffner's Bach statue that was erected in front of this church in 1908.

- ^ For the history of the monument cf. Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach, pp. 13–15; Hartmut Ellrich: Bach in Thüringen, p. 54. As a replacement for St. George's, the German Christian bishop Martin Sasse commissioned a new Bach statue from the Berlin sculptor Paul Birr, which was unveiled in 1939. For the history of this statue, that stands to the present day in St. George's, cf. Jörg Hansen and Gerald Vogt: Blood and Spirit, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Bachhaus mit Lichtkunst. News service www.eisenachonline.de, 21 March 2011. Accessed 16 November 2011.

- ^ Bachhaus-Ausstellung vom ADC ausgezeichnet. News service www.museumsreport.de, 17 April 2008. Last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ Begehbares Musikstück des Bachhauses ausgezeichnet. News service www.museumsreport.de, 20 May 2008. Last checked 16 November 2011.

- ^ Atelier Brueckner erhält Deutschen Innenarchitekturpreis. News service www.museumsreport.de, 11 November 2008. Accessed 16 November 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach – The Learned Musician.W.W. Norton, New York, 2000 (2. Aufl.). ISBN 978-3-596-16739-5

- Martin Petzoldt: Bachstätten. Ein Reiseführer zu Johann Sebastian Bach. Insel, Frankfurt, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04825-X

- Hartmut Ellrich: Bach in Thüringen. Sutton, Erfurt, 2011 (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-3-86680-856-0

- Ilse Domizlaff: Das Bachhaus Eisenach: Fakten und Dokumente. Bachhaus, Eisenach 1984.

- Conrad Freyse: Fünfzig Jahre Bachhaus. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1958.

- Wolfgang Heyde: Historische Musikinstrumente im Bachhaus Eisenach, Bachhaus, Eisenach, 1976.

- Jörg Hansen: Bachhaus Eisenach (English). Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg, 2011 (5th ed.). ISBN 978-3-7954-4008-4

- Jörg Hansen: 100 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach. Neubau, Altbausanierung, Neugestaltung der ständigen Ausstellung und feierliche Eröffnung am 17. Mai 2007. In: Thüringer Museumshefte. 16, 2007, 1, pp. 101–112.

- Jörg Hansen: 10 Jahre Bachhaus Eisenach gGmbH. Ein Erfahrungsbericht. In: Thüringer Museumshefte. 20, 2011, 1, pp. 48–61.

- Jörg Hansen, Gerald Vogt: Blood and Spirit – Bach, Mendelssohn and their music in the Third Reich (exhibition catalogue). Bachhaus, Eisenach 2009. ISBN 978-3-932257-06-3.