Anti-Bolshevik propaganda

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Anti-Bolshevik propaganda was created in opposition to the events on the Russian political scene. The Bolsheviks were a radical and revolutionary wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which came to power during the October Revolution phase of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The word "Bolshevik" (большевик) means "one of the majority" in Russian and is derived from the word "большинство" (transliteration: bol'shinstvo, see also Romanization of Russian) which means "majority" in English. The group was founded at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party when Vladimir Lenin's followers gained majority on the party’s central committee and on the editorial board of the newspaper Iskra. Their opponents were the Mensheviks, whose name literally means "Those of the minority" and is derived from the word меньшинство ("men'shinstvo", English: minority).

On 7 November 1917, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR; Russian: Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, transliteration: Rossiyskaya Sovetskaya Federativnaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika) was proclaimed. The Bolsheviks changed their name to Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in March 1918; to All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in December 1925; and to Communist Party of the Soviet Union in October 1952.

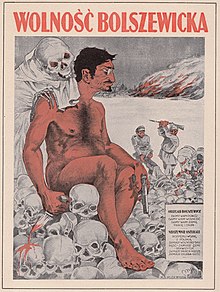

Anti-Bolshevik propaganda in Poland[edit]

Polish Anti-Bolshevik propaganda was most actively circulated during the Polish–Soviet War. In 1918, Poland regained its statehood for the first time since 1795, the year of the Third Partition of Poland between Prussia, Russia and Austria. The new Polish territory included lands from all the dismembered empires (see Second Polish Republic). The first independent ruler of Poland since the end of the 18th century, the Chief-of-State, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Republic was a devout anti-communist Józef Piłsudski. The war started as a conflict over Polish Borderlands and the subsequent Soviet invasion.

The Soviets circulated their own propaganda materials among Polish soldiers and civilians, urging them to join the fight for the "liberation of working people and against their oppressors and bourgeoisie". Letters and appeals portrayed Soviet Russia as a workers' utopia, where the worker has the highest power in the country.[1]

There were also active pro-Bolshevik movements in Poland. The main actor was the Communist Party of Poland, which was founded in December 1918 and was opposed to the war with the Bolsheviks. The Communist Party of Poland organized soldiers' councils (so-called soviets) which then engaged into circulating anti-Polish propaganda.

Propaganda posters[edit]

In the beginning of the 20th century posters were a popular form of communication. Posters were relatively efficient as they conveyed the message in a shortened form and could easily reach a big part of the population.[2] Posters were hung on walls, trees, in store windows and displayed during demonstrations.

Organizations that were responsible for the design and circulation of posters were Komitet Obrony Kresów Wschodnich (English: Committee for Protection of the Eastern Borderlands) and Straż Kresowa (English: Borderlands Guard). Other organs were Propaganda Bureau in the Presidium of the Council of Ministers (Polish: Biuro Propagandy Wewnętrznej przy prezydium Rady Ministrów), Section of Civil Propaganda of the Committee for State Protection (Polish: Sekcja Propagandy Obywatelskiego Komitetu Obrony Państwa and the Central Committee of Propaganda (Polish: Centralny Komitet Propagandy), run by artists.

For the purpose of the anti-Bolshevik propaganda during the war Polish artists created posters. Some of the authors were Felicjan Kowarski, Władysław Skoczylas, Edmund Bartłomiejczyk, Kajetan Stefanowicz, Władysław Jarocki, Zygmunt Kamiński, Edmund John, Kamil Mackiewicz, Stanisław Stawiczewski, Witold Gordon and Aleksander Grzybowski. Some of the posters are anonymous. The biggest number of posters, designed by Felicjan Szczęsny-Kowarski, Witold Gordon and Edmund John, were published by "Litografia Artystyczna Władysław Górczewski". Other publishers included private printing houses, such as "Zakład Graficzny Bolesław Wirtz", "Zakład Graficzny Straszewiczów", "Zakład Graficzny B.Wierzbicki i S-ka", "Zakłady Graficzne Koziańskich" and "Jan Cotty".[3]

Style[edit]

In contrast to the avant-garde Soviet posters, Polish posters are characterized by references to Romanticism, Impressionism, Symbolism, realistic historical painting and Young Poland.[2] They commonly utilized caricature.[3]

Topics[edit]

- Antisemitism. During the Polish-Soviet War, some people believed that Jews were responsible for the October Revolution, or even that the Bolshevik movement was an effect of a Jewish conspiracy. This led to the formation of the stereotype of the Jew-Communist, belonging to what was pejoratively called Żydokomuna (English: Judeo-Communism; see also Jewish Bolshevism).

- Vision of Poland under the Soviet rule. Poland under the Soviet hegemony was portrayed as a dystopia: it was characterized by destruction, fire, poverty and hunger.[3]

- Religion. The authors have referred to religious beliefs of Poles, which were largely Catholic. The militantly atheist Bolsheviks were thus presented as the enemy of the Catholic Church. The poster "Do broni! Tak wygląda wieś zajęta przez bolszewików" (English: To the Arms! This is what a village conquered by the Bolsheviks look like!") by Eugeniusz Nieczuja-Urbański presents a destroyed village, where the only remaining and intact part of the demolished church is a cross with Jesus Christ. Another one, "Kto w Boga wierzy – w Obronie Ostrobramskiej, pod sztandar Orła i Pogoni" ("Whoever believes in God, should protect Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn, under the Flag of the Eagle and Pahonia.") urges religious Poles to protect their homeland. It is also suggested that due to the monstrosity of the Bolsheviks, one has to entrust their fate to the Providence in order to successfully fight the enemy. The conflict is presented as a fight between Christians and non-Christians, or anti-Christians.[2]

- Animalization, dehumanization and demonization of the Bolsheviks. The Bolshevik soldier is portrayed as a barbarian, an uncivilized, wild, primivite person. Their faces are portrayed caricaturally, with unproportioned features. The Bolsheviks are pictured as cruel and demonic or monster-like creatured. The color red is dominating in the pictures, as it was associated with communism. The enemies are often surrounded by blood: dripping from a knife (for example held in teeth), on hands or standing in a river of blood.[2]

Notable examples[edit]

Small caption in the lower right corner reads:

The Bolsheviks promised:

We'll give you peace

We'll give you freedom

We'll give you land

Work and bread

Despicably they cheated

They started a war

With Poland

Instead of freedom they brought

The fist

Instead of land – confiscation

Instead of work – misery

Instead of bread – famine.

- The poster "Hej, kto Polak, na bagnety!" (English: "Hey, whoever is a Pole, to your bayonette!"). The quote originates from the Polish patriotic poem and celebratory anthem "Rota", written by the poet and an activist for Polish independence Maria Konopnicka. The poster features three men, seemingly belonging to different social groups, but uniting in fight.

- The poster "Bij Bolszewika" (English: "Beat the Bolshevik!") portraying a Polish soldier fighting a red, three-headed dragon symbolizing the enemy.

- The poster "Do broni. Wstępujcie do Armji Ochotniczej!" (English: "To the arms! Join the volunteer army!"), where the Bolshevik enemy is portrayed as three-headed dragon, breathing fire. Fighting the hydra is a Polish soldier.

- The poster "Potwór Bolszewicki" (English: "The Bolshevik Monster"), where the enemy is presented a skeleton riding a two-headed horse with heads of Vladimir Lenin and Lev Trotsky.

Contemporary usage[edit]

Currently, 41 anti-Bolshevik posters are displayed in the Museum of Independence in Warsaw.[4]

Anti-Bolshevik propaganda in Germany[edit]

The anti-Bolshevik and anti-communist propaganda in Germany was created and circulated by the Anti-Bolshevik League (German: Antibolschewistische Liga), later renamed to the League for Protection of German Culture (German: Liga zum Schutze der deutschen Kultur). The Anti-Bolshevist League was a radical right-wing organization, founded in December 1918 by Eduard Stadtler.

Anti-Bolshevik propaganda in Russia[edit]

Postcards[edit]

Anti-Bolshevik postcards were circulated by the Volunteer Army (Russian: Добровольческая армия; transliteration: Dobrovolcheskaya armiya). The White Volunteer Army was an army in South Russia during the Russian Civil War that fought the Bolsheviks. It has to be noted that the Propaganda Bureau of the Volunteer Army produced less postcards than the Bolshevik government.[5] According to the researcher Tobie Mathew, the anti-Bolshevik cards are amongst the scarcest of all Russian postcards for two reasons: firstly, they were "politically incorrect" in the Soviet Union and, secondly, only a small number of cards was issued to begin with. It has to be noted that the Bolsheviks, were far more successful in printing their propaganda materials, as control over printed media was considered a high priority by Lenin. After 1917, the Bolsheviks took over many previously privately-owned printing houses across Russia.

Postcards and posters were generally preferred as a part of the Russian population was illiterate, which made books and pamphlets less effective. The main publishers of the Bolshevik propaganda were Litizdat and Gosizdat (Russian: Госиздат; English: State Publisher). Since many Russians with anti-Bolshevik sympathies had fled the country or were attempting to, and the White Army was constantly changing its location, most of the postcards were printed in the northern and south-western borderlands of the former Russian Empire, particularly in Finland and the Baltic States, and under the pro-German government in Ukraine in 1918. For security reasons, the postcards were usually transported by trains and distributed by hand.

References[edit]

- ^ Davies, Norman. White eagle, red star the Polish-Soviet war, 1919–20 and the miracle on the Vistula. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0356040134. OCLC 758817989.

- ^ a b c d Dymarczyk, Waldemar. "The War on the Wall. Polish and Soviet War Posters Analysis" (PDF). Qualitative Sociology Review.

- ^ a b c Szczotka, Sylwia. "WIZERUNEK BOLSZEWIKA W POLSKICH PLAKATACH PROPAGANDOWYCH Z WOJNU POLSKO-ROSYJSKIEJ 1919–1920 ROKU ZE ZBIORÓW MUZEUM NIEPODLEGŁOŚCI" (PDF). Muzeum Niepodległości w Warszawie.

- ^ "Muzeum Niepodległości".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mathew, Tobie (1 December 2010). "'wish You Were (not) Here': Anti‐Bolshevik Postcards of the Russian Civil War, 1918–21". Revolutionary Russia. 23 (2): 183–216. doi:10.1080/09546545.2010.523070. ISSN 0954-6545.