Angomonas deanei

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Angomonas deanei | |

|---|---|

| |

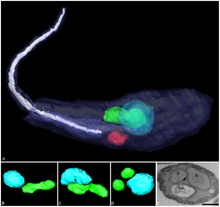

| Three-dimensional reconstruction of Angomonas deanei containing a bacterial endosymbiont (green) near its nucleus (blue). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Euglenozoa |

| Class: | Kinetoplastea |

| Order: | Trypanosomatida |

| Family: | Trypanosomatidae |

| Genus: | Angomonas |

| Species: | A. deanei |

| Binomial name | |

| Angomonas deanei (Carvalho, 1973) Teixeira & Camargo, 2011[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| Crithidia deanei Carvalho, 1973 | |

Angomonas deanei is a flagellated trypanosomatid protozoan. As an obligate parasite, it infects the gastrointestinal tract of insects, and is in turn a host to symbiotic bacteria. The bacterial endosymbiont Ca. "Kinetoplastibacterium crithidii" maintains a permanent mutualistic relationship with the protozoan such that it is no longer able to reproduce and survive on its own.[2] The symbiosis, subsequently also discovered in varying degrees in other protists such as Strigomonas culicis, Novymonas esmeraldas, Diplonema japonicum and Diplonema aggregatum are considered as good models for the understanding of the evolution of eukaryotes from prokaryotes,[3][4][5] and on the origin of cell organelles (i.e. symbiogenesis).[6][7]

The species was first described as Crithidia deanei in 1973 by a Brazilian parasitologist Aurora L. M. Carvalho. A phylogenetic analysis in 2011 revealed that it belongs to the genus Angomonas, thereby becoming Angomonas deanei. The symbiotic bacterium is a member of the β-proteobacterium that descended from the common ancestor with the genus Bordetella,[1] or more likely, Taylorella.[8] The two organisms have depended on each other so much that the bacterium cannot reproduce and the protozoan can no longer infect insects when they are isolated.[9][10]

Discovery[edit]

Angomonas deanei was originally described as Crithidia deanei. In 1973, a Brazilian graduate student Aurora Luiza de Moura Carvalho at the Universidade Federal de Goiás[11] discovered the species from his study of intestinal parasites of the assassin bugs in Goiás.[12] The next year he reported that the bug Zelus leucogrammus from which he discovered was not naturally infected by the protozoan, but it was acquired from other insects.[11] At the same time, a research team at the Universidade de Brasilia reported the biochemical properties and structural details based on transmission electron microscopy. They discovered that it harbours an endosymbiont, describing it as "probably bacterial" that provided the "trypanosomatid essential nutrients."[13] The bacterial nature of the endosymbiont was confirmed in 1977 when it was shown that it could be killed by treating with an antibiotic chloramphenicol,[14] and that it helps the host in synthesising the amino acid arginine from ornithine.[15]

As more structural and molecular details were studied, the distinction of A. deanei from other Crithidia species became more pronounced. In 1991, Maria Auxiliadora de Sousa and Suzana Corte-Real at the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz proposed a new genus Angomonas for the species.[16][17] Phylogenetic study by Marta M.G. Teixeira and Erney P. Camargo at the University of São Paulo with their collaborators in 2011 validated the new species name A. deanei along with a description of a new related species A. ambiguus, which also contains the same bacterial endosymbiont.[1]

Structure[edit]

The body of Angomonas deanei is elliptical in shape, with a prominent tail-like flagellum at its posterior end for locomotion. The bacterial endosymbiont is inside its body and is surrounded by two cell membranes typical of Gram-negative bacteria, but its cell membrane presents unusual features, such as the presence of phosphatidylcholine, a major membrane lipid (atypical of bacterial membranes), and the highly reduced peptidoglycan layer, which shows reduced or absence of rigid cell wall. The cell membrane of the protozoan host contains an 18-domain β-barrel porin, which is a characteristic protein of Gram-negative bacteria, and unusual of eukaryotes.[18] In addition it contains cardiolipin and phosphatidylcholine as the major phospholipids, while sterols are absent.[19] Cardiolipin is a typical lipid of bacterial membranes; phosphatidylcholine, on the other hand, is mostly present in symbiotic prokaryotes of eukaryotic cells. For symbiotic adaptation, the protozoan host has undergone alterations such as reduced paraflagellar rod, which is required for full motility of the bacterial flagella. Yet the paraflagellar rod gene PFR1 is fully functional.[20] It also lacks introns and transcription of long polycistronic mRNAs required by other eukaryotes for complex gene activities.[21] Its entire genome is distributed in 29 chromosomes and contains 10,365 protein-coding genes, 59 transfer RNAs, 26 ribosomal RNAs, and 62 noncoding RNAs.[22]

While the protozoan has its separate mitochondria that provide electron transport system for the production of cellular energy, the ATP molecules are produced through its glycosomes.[9] The bacterium is known to provide essential nutrients to the host. It synthesises amino acids,[23] vitamins,[24] nitrogenous bases and haem[25] for the protozoan. Haem is necessary for the growth and development of the protozoan.[21] The bacterium also provides the enzymes for urea cycle which are absent in the host. In return the protozoan offers its enzymes for the complete metabolic pathways for the biosynthesis of amino acids, lipids and nucleotides, that are absent in the bacterium.[26] The bacterium has highly reduced genome compared to its related bacterial species, lacking many genes essential for its survival.[21] Phosphatidylinositol, a membrane lipid required for cell-cell interaction in the bacteria is also synthesised by the protozoan.[27] The bacterium also depends on the host for ATP molecules for its energetic functions. Thus, the two organisms intimately share and exchange their metabolic systems.[9]

When the bacterium is killed using antibiotics, the protozoan can no longer infect insects,[10] due to the altered glycosylphosphatidylinositol (gp63) in the protozoan flagellum.[28] A bacterium-less protozoan exhibits reduced gene activities; particularly those involved in oxidation-reduction process, ATP hydrolysis-coupled proton transport and glycolysis are stopped.[29] The structural components are also altered including cell surface, carbohydrate composition, paraflagellar rod and kinetoplast.[30]

Parasitism[edit]

Angomonas deanei was originally discovered from the digestive tract of the bug Zelus leucogrammus. But it was realised that the bugs are not heavily infected and were likely transmitted from other insects.[11] It is now known to infect different mosquitos,[31] and flies,[32] and capable of infecting mammalian fibroblast cells under experimental conditions.[33][34] Transmission from one insect to another occurs between adults (horizontal transmission) only, and the protozoan cannot fix itself in the hindgut of insect larvae. The flagellum is used as an adhesive organ that gets attached near the rectal glands and sometime directly on the surface of the rectal glands.[35]

Reproduction[edit]

The cellular reproduction shows a strong synergistic adaptation between the bacterium and the protozoan. The bacterium divides first, followed by the protozoan organelles, and lastly the nucleus. As a result the daughter protozoans contains exactly the same copies of the organelles and the bacterial endosymbiont.[36] The entire reproduction takes about 6 hours in an ideal culture medium; thus, a single protozoan is able to produce 256 daughter cells in a day, though it can differ slightly under its natural habitat.[21]

The endosymbiont and evolution[edit]

Symbiotic bacteria in the trypanosomatid protozoa are descended from a β-proteobacterium.[37] With A. deanei, the bacteria Ca. "Kinetoplastibacterium crithidii" have co-evolved in a mutualistic relationship characterised by intense metabolic exchanges. The endosymbiont contains enzymes and metabolic precursors that complete essential biosynthetic pathways of the host protozoan, such as those in the urea cycle and the production of haemin and polyamine.[38]

The symbiotic bacterium belongs to β-proteobacterium family Alcaligenaceae. Based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences, it is known that it originated from a common ancestor with the one in Strigomonas culicis. The two groups are assumed to enter two different host protozoans to evolve into different species. Hence the scientific name (Candidatus) Kinetoplastibacterium crithidii was given to the bacterium.[39] Although it was initially proposed that the bacterium evolved from a common ancestor with members of Bordetella,[1] however, detailed phylogenomic analysis revealed that it is more closely related to members of the genus Taylorella.[8] Re-analysis by GTDB finds the genus sister to Proftella, a symbiont of Diaphorina citri.[40]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Teixeira MM, Borghesan TC, Ferreira RC, Santos MA, Takata CS, Campaner M, Nunes VL, Milder RV, de Souza W, Camargo EP (2011). "Phylogenetic validation of the genera Angomonas and Strigomonas of trypanosomatids harboring bacterial endosymbionts with the description of new species of trypanosomatids and of proteobacterial symbionts". Protist. 162 (3): 503–524. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2011.01.001. PMID 21420905.

- ^ Labinfo. "Angomonas deanei". labinfo.lncc.br. National Laboratory of Scientific Computation of the Ministry of Science and Technology, Brazil. Archived from the original on 2013-07-30. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ^ de Souza, Silvana Sant´Anna; Catta-Preta, Carolina Moura; Alves, João Marcelo P.; Cavalcanti, Danielle P.; Teixeira, Marta M. G.; Camargo, Erney P.; De Souza, Wanderley; Silva, Rosane; Motta, Maria Cristina M. (2017). Yurchenko, Vyacheslav (ed.). "Expanded repertoire of kinetoplast associated proteins and unique mitochondrial DNA arrangement of symbiont-bearing trypanosomatids". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0187516. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1287516D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187516. PMC 5683618. PMID 29131838.

- ^ Motta, Maria Cristina Machado; Martins, Allan Cezar de Azevedo; de Souza, Silvana Sant'Anna; Catta-Preta, Carolina Moura Costa; Silva, Rosane; Klein, Cecilia Coimbra; de Almeida, Luiz Gonzaga Paula; de Lima Cunha, Oberdan; Ciapina, Luciane Prioli; Brocchi, Marcelo; Colabardini, Ana Cristina (2013). "Predicting the proteins of Angomonas deanei, Strigomonas culicis and their respective endosymbionts reveals new aspects of the trypanosomatidae family". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60209. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860209M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060209. PMC 3616161. PMID 23560078.

- ^ Tashyreva, Daria; Prokopchuk, Galina; Votýpka, Jan; Yabuki, Akinori; Horák, Aleš; Lukeš, Julius (2018-05-02). Heitman, Joseph (ed.). "Life Cycle, Ultrastructure, and Phylogeny of New Diplonemids and Their Endosymbiotic Bacteria". mBio. 9 (2). João M. P. Alves, John McCutcheon. doi:10.1128/mBio.02447-17. ISSN 2161-2129. PMC 5845003. PMID 29511084.

- ^ Kostygov, Alexei Y.; Dobáková, Eva; Grybchuk-Ieremenko, Anastasiia; Váhala, Dalibor; Maslov, Dmitri A.; Votýpka, Jan; Lukeš, Julius; Yurchenko, Vyacheslav (2016-03-15). "Novel Trypanosomatid-Bacterium Association: Evolution of Endosymbiosis in Action". mBio. 7 (2): e01985. doi:10.1128/mBio.01985-15. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 4807368. PMID 26980834.

- ^ Husnik, Filip; Keeling, Patrick J (2019). "The fate of obligate endosymbionts: reduction, integration, or extinction". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 58–59: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2019.07.014. PMID 31470232. S2CID 201731819.

- ^ a b Alves JM, Serrano MG, Maia da Silva F, Voegtly LJ, Matveyev AV, Teixeira MM, Camargo EP, Buck GA (2013). "Genome evolution and phylogenomic analysis of Candidatus Kinetoplastibacterium, the betaproteobacterial endosymbionts of Strigomonas and Angomonas". Genome Biol Evol. 5 (2): 338–350. doi:10.1093/gbe/evt012. PMC 3590767. PMID 23345457.

- ^ a b c Motta, M. C.; Soares, M. J.; Attias, M.; Morgado, J.; Lemos, A. P.; Saad-Nehme, J.; Meyer-Fernandes, J. R.; De Souza, W. (1997). "Ultrastructural and biochemical analysis of the relationship of Crithidia deanei with its endosymbiont". European Journal of Cell Biology. 72 (4): 370–377. PMID 9127737.

- ^ a b d'Avila-Levy CM, Silva BA, Hayashi EA, Vermelho AB, Alviano CS, Saraiva EM, Branquinha MH, Santos AL (2005). "Influence of the endosymbiont of Blastocrithidia culicis and Crithidia deanei on the glycoconjugate expression and on Aedes aegypti interaction". FEMS Microbiol Lett. 252 (2): 279–286. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.012. PMID 16216441.

- ^ a b c Carvalho, A. L.; Deane, M. P. (1974). "Trypanosomatidae isolated from Zelus leucogrammus (Perty, 1834) (Hemiptera, Reduviidae), with a discussion on flagellates of insectivorous bugs". The Journal of Protozoology. 21 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1974.tb03605.x. PMID 4594242.

- ^ Carvalho, Aurora Luiza de Moura (1973). "Estudos sobre a posição sistemática, a biologia e a transmissào de tripanosomatídeos encontrados em Zelus leucogrammus (Perty, 1834) (Hemiptera, Reduviidae)". Rev. Pat. Trop. (in Portuguese). 2 (2): 223–274.

- ^ Mundim, Maria Hermelinda; Roitman, Isaac; Hermans, Maria A.; Kitajima, Elliot W. (1974). "Simple Nutrition of Crithidia deanei , a Reduviid Trypanosomatid with an Endosymbiont*". The Journal of Protozoology. 21 (4): 518–521. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1974.tb03691.x. PMID 4278787.

- ^ Mundim, Maria Hermelinda; Roitman, Isaac (1977). "Extra Nutritional Requirements of Artificially Aposymbiotic Crithidia deanei *". The Journal of Protozoology. 24 (2): 329–331. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1977.tb00988.x.

- ^ Camargo, E. Plessmann; Freymuller, Edna (1977). "Endosymbiont as supplier of ornithine carbamoyltransferase in a trypanosomatid". Nature. 270 (5632): 52–53. Bibcode:1977Natur.270...52C. doi:10.1038/270052a0. PMID 927516. S2CID 4210642.

- ^ Sousa, M.A. (1991). "Postnuclear kinetoplast in choanomastigotes of Crithidia deanei Carvalho, 1973. Proposal of a new genus". Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 33: S8.

- ^ Teixeira, Marta M. G.; Takata, Carmen S. A.; Conchon, Ivete; Campaner, Marta; Camargo, Erney P. (1997). "Ribosomal and kDNA Markers Distinguish Two Subgroups of Herpetomonas among Old Species and New Trypanosomatids Isolated from Flies". The Journal of Parasitology. 83 (1): 58–65. doi:10.2307/3284317. JSTOR 3284317. PMID 9057697.

- ^ Andrade Ida S, Vianez-Júnior JL, Goulart CL, Homblé F, Ruysschaert JM, Almeida von Krüger WM, Bisch PM, de Souza W, Mohana-Borges R, Motta MC (2011). "Characterization of a porin channel in the endosymbiont of the trypanosomatid protozoan Crithidia deanei". Microbiology. 157 (Pt 10): 2818–2830. doi:10.1099/mic.0.049247-0. PMID 21757490.

- ^ Palmié-Peixoto IV, Rocha MR, Urbina JA, de Souza W, Einicker-Lamas M, Motta MC (2006). "Effects of sterol biosynthesis inhibitors on endosymbiont-bearing trypanosomatids". FEMS Microbiol Lett. 255 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00056.x. PMID 16436059.

- ^ Gadelha C, Wickstead B, de Souza W, Gull K, Cunha-e-Silva N (2005). "Cryptic paraflagellar rod in endosymbiont-containing kinetoplastid protozoa". Eukaryot Cell. 4 (3): 516–525. doi:10.1128/EC.4.3.516-525.2005. PMC 1087800. PMID 15755914.

- ^ a b c d Morales, Jorge; Kokkori, Sofia; Weidauer, Diana; Chapman, Jarrod; Goltsman, Eugene; Rokhsar, Daniel; Grossman, Arthur R.; Nowack, Eva C. M. (2016). "Development of a toolbox to dissect host-endosymbiont interactions and protein trafficking in the trypanosomatid Angomonas deanei". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16 (1): 247. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0820-z. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5106770. PMID 27835948.

- ^ Davey, John W; Catta-Preta, Carolina M C; James, Sally; Forrester, Sarah; Motta, Maria Cristina M; Ashton, Peter D; Mottram, Jeremy C (2021). Andrews, B (ed.). "Chromosomal assembly of the nuclear genome of the endosymbiont-bearing trypanosomatid Angomonas deanei". G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 11 (1): jkaa018. doi:10.1093/g3journal/jkaa018. ISSN 2160-1836. PMC 8022732. PMID 33561222.

- ^ Alves, João MP; Klein, Cecilia C; da Silva, Flávia; Costa-Martins, André G; Serrano, Myrna G; Buck, Gregory A; Vasconcelos, Ana Tereza R; Sagot, Marie-France; Teixeira, Marta MG; Motta, Maria Cristina M; Camargo, Erney P (2013). "Endosymbiosis in trypanosomatids: the genomic cooperation between bacterium and host in the synthesis of essential amino acids is heavily influenced by multiple horizontal gene transfers". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1): 190. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-190. PMC 3846528. PMID 24015778.

- ^ Klein, Cecilia C.; Alves, João M. P.; Serrano, Myrna G.; Buck, Gregory A.; Vasconcelos, Ana Tereza R.; Sagot, Marie-France; Teixeira, Marta M. G.; Camargo, Erney P.; Motta, Maria Cristina M.; Parkinson, John (2013). "Biosynthesis of vitamins and cofactors in bacterium-harbouring trypanosomatids depends on the symbiotic association as revealed by genomic analyses". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e79786. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879786K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079786. PMC 3833962. PMID 24260300.

- ^ Alves, João M. P.; Voegtly, Logan; Matveyev, Andrey V.; Lara, Ana M.; da Silva, Flávia Maia; Serrano, Myrna G.; Buck, Gregory A.; Teixeira, Marta M. G.; Camargo, Erney P. (2011). "Identification and phylogenetic analysis of heme synthesis genes in trypanosomatids and their bacterial endosymbionts". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23518. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623518A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023518. PMC 3154472. PMID 21853145.

- ^ Motta MC, Martins AC, de Souza SS, Catta-Preta CM, Silva R, Klein CC, de Almeida LG, de Lima Cunha O, Ciapina LP, Brocchi M, Colabardini AC, de Araujo Lima B, Machado CR, de Almeida Soares CM, Probst CM, de Menezes CB, Thompson CE, Bartholomeu DC, Gradia DF, Pavoni DP, Grisard EC, Fantinatti-Garboggini F, Marchini FK, Rodrigues-Luiz GF, Wagner G, Goldman GH, Fietto JL, Elias MC, Goldman MH, Sagot MF, Pereira M, Stoco PH, de Mendonça-Neto RP, Teixeira SM, Maciel TE, de Oliveira Mendes TA, Ürményi TP, de Souza W, Schenkman S, de Vasconcelos AT (2013). "Predicting the proteins of Angomonas deanei, Strigomonas culicis and their respective endosymbionts reveals new aspects of the trypanosomatidae family". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60209. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860209M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060209. PMC 3616161. PMID 23560078.

- ^ de Azevedo-Martins, Allan C; Alves, João MP; Garcia de Mello, Fernando; Vasconcelos, Ana Tereza R; de Souza, Wanderley; Einicker-Lamas, Marcelo; Motta, Maria Cristina M (2015). "Biochemical and phylogenetic analyses of phosphatidylinositol production in Angomonas deanei, an endosymbiont-harboring trypanosomatid". Parasites & Vectors. 8 (1): 247. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0854-x. PMC 4424895. PMID 25903782.

- ^ d'Avila-Levy CM, Santos LO, Marinho FA, Matteoli FP, Lopes AH, Motta MC, Santos AL, Branquinha MH (2008). "Crithidia deanei: influence of parasite gp63 homologue on the interaction of endosymbiont-harboring and aposymbiotic strains with Aedes aegypti midgut". Exp Parasitol. 118 (3): 345–353. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2007.09.007. PMID 17945218.

- ^ Penha, Luciana Loureiro; Hoffmann, Luísa; Souza, Silvanna Sant'Anna de; Martins, Allan Cézar de Azevedo; Bottaro, Thayane; Prosdocimi, Francisco; Faffe, Débora Souza; Motta, Maria Cristina Machado; Ürményi, Turán Péter; Silva, Rosane (2016). "Symbiont modulates expression of specific gene categories in Angomonas deanei". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 111 (11): 686–691. doi:10.1590/0074-02760160228. PMC 5125052. PMID 27706380.

- ^ Souza, Wanderley; Motta, Maria Cristina Machado (1999). "Endosymbiosis in protozoa of the Trypanosomatidae family". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 173 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13477.x. ISSN 0378-1097. PMID 10220875.

- ^ D'Avila-Levy, Claudia M.; Silva, Bianca A.; Hayashi, Elize A.; Vermelho, Alane B.; Alviano, Celuta S.; Saraiva, Elvira M.B.; Branquinha, Marta H.; Santos, André L.S. (2005). "Influence of the endosymbiont of Blastocrithidia culicis and Crithidia deanei on the glycoconjugate expression and on Aedes aegypti interaction". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 252 (2): 279–286. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.012. PMID 16216441.

- ^ Borghesan, Tarcilla C.; Campaner, Marta; Matsumoto, Tania E.; Espinosa, Omar A.; Razafindranaivo, Victor; Paiva, Fernando; Carranza, Julio C.; Añez, Nestor; Neves, Luis; Teixeira, Marta M. G.; Camargo, Erney P. (2018). "Genetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Relationships of Coevolving Symbiont-Harboring Insect Trypanosomatids, and Their Neotropical Dispersal by Invader African Blowflies (Calliphoridae)". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 131. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00131. PMC 5808337. PMID 29467742.

- ^ Santos, Dilvani O.; Bourguignon, Saulo C.; Castro, Helena Carla; Silva, Jonatan S.; Franco, Leonardo S.; Hespanhol, Renata; Soares, Maurilio J.; Corte-Real, Suzana (2004). "Infection of Mouse Dermal Fibroblasts by the Monoxenous Trypanosomatid Protozoa Crithidia deanei and Herpetomonas roitmani". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 51 (5): 570–574. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00293.x. PMID 15537092. S2CID 5830694.

- ^ Matteoli, Filipe P.; d’Avila-Levy, Claudia M.; Santos, Lívia O.; Barbosa, Gleyce M.; Holandino, Carla; Branquinha, Marta H.; Santos, André L.S. (2009). "Roles of the endosymbiont and leishmanolysin-like molecules expressed by Crithidia deanei in the interaction with mammalian fibroblasts". Experimental Parasitology. 121 (3): 246–253. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2008.11.011. PMID 19070618.

- ^ Ganyukova, Anna I.; Malysheva, Marina N.; Frolov, Alexander O. (2020). "Life cycle, ultrastructure and host-parasite relationships of Angomonas deanei (Kinetoplastea: Trypanosomatidae) in the blowfly Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae)" (PDF). Protistology. 14 (4): 204–218. doi:10.21685/1680-0826-2020-14-4-2.

- ^ Motta MC, Catta-Preta CM, Schenkman S, de Azevedo Martins AC, Miranda K, de Souza W, Elias MC (2010). "The bacterium endosymbiont of Crithidia deanei undergoes coordinated division with the host cell nucleus". PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e12415. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512415M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012415. PMC 2932560. PMID 20865129.

- ^ Du Y, McLaughlin G, Chang KP (1994). "16S ribosomal DNA sequence identities of beta-proteobacterial endosymbionts in three Crithidia species". Journal of Bacteriology. 176 (10): 3081–3084. doi:10.1128/jb.176.10.3081-3084.1994. PMC 205468. PMID 8188611.

- ^ Frossard ML, Seabra SH, DaMatta RA, de Souza W, de Mello FG, Machado Motta MC (2006). "An endosymbiont positively modulates ornithine decarboxylase in host trypanosomatids". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 343 (2): 443–449. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.168. PMID 16546131.

- ^ Du Y, Maslov DA, Chang KP (1994). "Monophyletic origin of beta-division proteobacterial endosymbionts and their coevolution with insect trypanosomatid protozoa Blastocrithidia culicis and Crithidia spp". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91 (18): 8437–8441. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.8437D. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.18.8437. PMC 44621. PMID 7521530.

- ^ "GTDB - Tree at g__Kinetoplastibacterium". gtdb.ecogenomic.org.