2015–2016 New Zealand flag referendums

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | First referendum: 1,546,734 (48.78%) Second referendum: 2,140,805 (67.78%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by electorate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

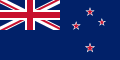

Two referendums were held by the New Zealand Government in November/December 2015 and March 2016 to determine the nation's flag. The voting resulted in the retention of the current flag of New Zealand.[1]

Shortly after the referendum announcement, party leaders reviewed draft legislation and selected candidates for a Flag Consideration Panel. The purpose of this group was to publicise the process, seek flag submissions and suggestions from the public, and decide on a final shortlist of options. Open consultation and design solicitation garnered 10,292 design suggestions from the public, later reduced to a "longlist" of 40 designs and then a "shortlist" of four designs to contend in the first referendum.[2][3] Following a petition, the shortlist was later expanded to include a fifth design, the Red Peak.

The first referendum took place between 20 November and 11 December 2015 and asked, "If the New Zealand flag changes, which flag would you prefer?"[4][5] Voters were presented with several options selected by the Flag Consideration Panel. The black, white, and blue silver fern flag by Kyle Lockwood advanced to the second referendum.

The second referendum took place between 3 and 24 March 2016. It asked voters to choose between the selected alternative (the black, white and blue silver fern flag) and the existing New Zealand flag.[6][7]

Reception of the process and the finalist designs were highly critical, with no great enthusiasm shown among the public.[8][9][10][11] From an aggregation of analyses, the consensus was that the referendum was "a bewildering process that seems to have satisfied few".[12]

Background and administration[edit]

New Zealand has a history of debate about whether the national flag should be changed. For several decades, alternative designs have been proposed, with varying degrees of support. There is no consensus among proponents of changing the flag as to which design should replace the flag.

In January 2014, Prime Minister John Key floated the idea of a referendum on a new flag at the 2014 general election.[13] The proposal was met with a mixed response.[14][15] Then in March, Key announced that New Zealand would hold a referendum within the next three years asking whether to change the flag design, if the National Party be re-elected for a third term.[16] Following National's re-election the details of the referendum were announced.[5]

Legal issues[edit]

The results of both referendums were binding, meaning the flag with the most votes in the second referendum would become the official flag of New Zealand.[17] In the unlikely event the second referendum vote was tied, an assumption for the status quo would have applied.[18]

If a new flag design had been chosen, assuming no intellectual property issues, the Flags, Emblems and Names Protection Act 1981 would have been updated to reflect the new design six months to the day after the second referendum results were declared (or earlier by Order in Council). The current flag would have remained the official flag until then; for example, the current flag would have been flown during the 2016 Summer Olympics, four months after the second referendum took place, regardless of the results of the second referendum. This result would not have changed the coat of arms (which includes the current national flag), the national Māori flag, the flags of Associated States (Cook Islands and Niue), or the New Zealand Red Ensign (merchant marine), White Ensign (naval), (both incorporating Union Flags) police flag and fire service flag (which are based on the current flag).[19] It would also not change New Zealand's status as a constitutional monarchy in the Commonwealth of Nations.[20]

Use of current flag[edit]

If the flag had been changed, it would have been legal to have continued to fly the current flag of New Zealand, which would have been "recognised as a flag of historical significance."[21] Old flags would have been replaced once worn out.[19][22] Official documents depicting the current flag, such as driver licences, would have been phased out as a matter of course – in the case of driver licences, this would have been when licences are renewed and would therefore have taken up to 10 years.

New Zealand Government ships and those non-government ships flying the New Zealand flag (instead of the New Zealand Red Ensign) would have been given an extra six months to change their flag to the new design. Ships flying the New Zealand Red Ensign and ships belonging to the New Zealand Defence Force would not have been affected by any flag changes, nor would any New Zealand-based ships registered to foreign countries.[23][24]

Cost of transition[edit]

The estimated cost of updating government flags and Defence Force uniforms was approximately $2.69 million. Other unknown costs include updating government ships, updating trademarks and logos, publicity of the new flag, excess stock of old flags (including products and souvenirs containing it), and updating all flags, packaging, uniforms and marketing material in the private and sporting sectors. The government would not have provided compensation for the cost of adopting the new flag.[19]

Pre-referendums process[edit]

Cross-party group[edit]

Shortly after announcing the referendum, party leaders were invited to a cross-party group. The purpose of the cross-party group was to review draft legislation allowing for the referendums to take place, and to nominate candidates for a Flag Consideration Panel by mid February 2015. Members included Bill English (Finance Minister and leader of the group), Jonathan Young (representing National), Trevor Mallard (representing Labour), Kennedy Graham (representing Green), Marama Fox (representing Māori), David Seymour (representing ACT) and Peter Dunne (representing United Future). New Zealand First refused to participate.[5][25][26]

Flag Consideration Panel[edit]

The Flag Consideration Panel was a separate group of "respected New Zealanders" with representative age, regional, gender and ethnic demographics. Their purpose was to publicise the process, seek flag submissions and suggestions from the public, and decide on a final shortlist of four suitable options for the first referendum. Public consultation took place between May and June 2015.[2][3] The panel stated that it consulted vexillologists (flag experts) and designers to ensure that the flags chosen were workable and had no impediments.[27] The members of the Flag Consideration Panel were:[28]

- Chair: John Burrows, former deputy chancellor of the University of Canterbury

- Deputy chair: Kate De Goldi, author

- Julie Christie, reality television producer

- Rod Drury, businessman

- Rhys Jones, former Chief of the New Zealand Defence Force

- Beatrice Faumuina, former discus thrower

- Brian Lochore, former All Blacks coach

- Nicky Bell, chief executive of New Zealand branch of Saatchi & Saatchi

- Peter Chin, former mayor of Dunedin

- Stephen Jones, youth councillor

- Malcolm Mulholland, academic

- Hana O'Regan, Māori studies academic

Referendums legislation[edit]

The legislation to set up the referendums passed its first Parliament hearing on 12 March 2015 with a vote of 76 to 43.[29] It was then considered by the Justice and Electoral Select Committee. During their public submission intake phase the RSA launched the "Fight for the Flag" campaign, also backed by New Zealand First, to reverse the question order and first ask if New Zealanders want a flag change.[30] Labour MP Trevor Mallard presented a petition signed by 30,000 people to the Committee, asking for a keep/change question to be added to the first referendum, similar to the 2011 voting system referendum.[31] During its second hearing in Parliament, MP Jacinda Ardern proposed an amendment so that the second referendum would only take place if turnout for the first referendum was at least 50%, as a way of ensuring majority rule and reducing costs if the public was apathetic. Ardern's proposal was voted down and the bill was passed as-is on 29 July 2015.[32]

Public engagement process[edit]

As part of the public engagement process, flag designs and symbolism/value suggestions were solicited until 16 July, which resulted in a total of 10,292 design suggestions.[6] All 10,292 submitted design proposals were presented to the public on the New Zealand government website.[33]

During the public engagement process, the Flag Consideration Panel travelled around the country for workshops and hui. These in-person consultation events were noted to have markedly low attendance.[8] The consideration panel noted strong online engagement with over 850,000 visits to the website and 1,180,000 engagements on social media.[34]

The panel reported that feedback found the themes of freedom, history, equality, respect and family to be the most significant to New Zealanders,[34] however it was later revealed that those themes were dwarfed by the amount of feedback critical of the flag change process.[9] From the submitted designs they found the most common colours were white, blue, red, black, and green. The most common elements incorporated into the flag designs were the Southern Cross, silver fern, kiwi, and koru. The main themes incorporated into the designs were Māori culture, nature and history.[34]

The flag of the United Tribes and the Tino Rangatiratanga flag were not considered as eligible options as a result of consultation with Māori groups.[35]

Long list[edit]

From the 10,292 submitted designs, the Flag Consideration Panel deliberations resulted in their selection of a "long list" shortlist of 40 designs (announced to the public on 10 August 2015).[36]

- Wā kāinga / Home by Studio Alexander [note 1]

- Land Of The Long White Cloud (Ocean Blue) by Mike Archer

- Land Of The Long White Cloud (Traditional Blue) by Mike Archer

- Huihui/Together by Sven Baker

- Silver Fern (Black & Silver) by Sven Baker

- Southern Cross Horizon by Sven Baker

- Southern Koru by Sven Baker

- Unity Koru by Sven Baker

- Inclusive by Dominic Carroll

- Moving Forward by Dominic Carroll

- The Seven Stars of Matariki by Matthew Clare

- Silver Fern (Green) by Roger Clarke

- Curly Koru by Daniel Crayford and Leon Cayford

- Koru Fin by Daniel Crayford and Leon Cayford

- Modern Hundertwasser koru by Tomas Cottle [note 2]

- NZ One by Travis Cunningham

- Black Jack by Mike Davison

- Unity Koru by Paul Densem

- New Southern Cross by Wayne William Doyle

- Red peak by Aaron Dustin

- Manawa (Black & Green) by Otis Frizzell

- Manawa (Blue & Green) by Otis Frizzell

- Embrace (Red & Blue) by Denise Fung

- Koru (Black) by Andrew Fyfe

- Koru (Blue) by Andrew Fyfe

- Unity Fern (Red & Blue) by Paul Jackways

- White and Black Fern by Alofi Kanter

- Silver Fern (Black and White) by Alofi Kanter

- New Zealand Matariki by John Kelleher

- Silver Fern (Black with Red Stars) by Kyle Lockwood

- Silver Fern (Red, White and Blue) by Kyle Lockwood

- Silver Fern (Black & White) by Kyle Lockwood

- Silver Fern (Black, White and Red) by Kyle Lockwood

- Silver Fern (Black, White and Blue) by Kyle Lockwood

- Pikopiko by Grant Pascoe

- Finding Unity in Community by Dave Sauvage

- Fern (Green, Black & White) by Clay Sinclair and Sandra Ellmers

- Koru and Stars by Alan Tran

- Raranga by Pax Zwanikken

- Tukutuku by Pax Zwanikken

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Wā kāinga won the top $20,000 prize in a privately organised competition run by the Gareth Morgan Foundation.[37]

- ^ The "Modern Hundertwasser" was later removed following a copyright claim from the Hundertwasser Non-Profit Foundation.[38]

Shortlist announcement and adjustment[edit]

On 1 September 2015, the Flag Consideration Panel announced the four designs to be included in the first referendum.[39] After public disappointment with the official shortlist, a social media campaign was launched on 2 September[40] for the Red Peak flag. On 23 September, the Green Party MP Gareth Hughes attempted to introduce a bill to parliament to include Red Peak as an option in the first referendum. Prime Minister John Key confirmed that the National Party would pick up the legislation, meaning the Red Peak flag was added as a fifth option in the flag referendum.[41]

| Image | Designer | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alofi Kanter | Silver Fern (Black and White) | A variation of the silver fern flag which included the silver fern and the black and white colour scheme.[42] This design uses counterchanging and the fern design from the New Zealand government's Masterbrand logo.[43] |

| Kyle Lockwood | Silver Fern (Red, White and Blue) | The silver fern represents the growth of the nation and the Southern Cross represents the location of New Zealand in the antipodes. The blue represents New Zealand's clear atmosphere and the Pacific Ocean. The red represents the country's heritage and sacrifices made.[44] This proposal won a Wellington newspaper flag competition in July 2004 and appeared on TV3 in 2005 after winning a poll which included the present national flag.[45] |

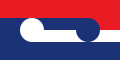

| Kyle Lockwood | Silver Fern (Black, White and Blue) | Variation of the above with black instead of red, and a different shade of blue. This general design was John Key's preferred proposal. This flag received similar feedback to the above variation. |

| Andrew Fyfe | Koru (Black) | Featured a Māori koru pattern depicting an unfurling fern frond, traditionally representing new life, growth, strength and peace. It was also meant to resemble a wave, cloud and ram's horn.[42] When this design was revealed on the shortlist, the public immediately nicknamed it "Hypnoflag" and "Monkey Butt" via social media.[51][52] |

| Aaron Dustin | Red Peak | This design was inspired by the story of Rangi and Papa (a Māori creation myth) and the geography of New Zealand. It is reminiscent of tāniko patterns, tukutuku panelling and the flag of the United Kingdom.[53] This design was not initially on the official shortlist but a social media campaign to add this design became successful on 23 September 2015.[54][55] The National Business Review noted that the design community generally preferred this design but it did not resonate with the public at large.[49] |

Criticism[edit]

The referendum process and alternative flag designs were heavily criticised.[56] Commentators identified many issues and reasons for failure, the most significant of which are listed below.

Politicisation[edit]

Prime Minister John Key's drive to run the referendums was seen as disproportionate compared to apathy among the public.[57] Members of parliament accused the referendums as Key's "vanity project", populist bread and circuses,[58][31] a distraction from poverty and housing issues, or a vehicle to establish a personal legacy.[26] In hindsight, the National Business Review suggests that politicisation contributed to the referendum's failure, because the debate and the alternative flag designs were so heavily associated with Key and the National Party rather than the actual flag change itself.[59][56][49] Key's campaigning was noted as perplexing and ineffectual. His statements on the topic of New Zealand's identity and colonial legacy were mixed, which confused the public.[49] Additionally, he relied on his own existing popularity as the face of the referendum to persuade the public,[60][61][62][63] with a change the flag campaign by Change the NZ Flag.[64] Opposition parties had hitherto supported a flag referendum as party policy, but took the opportunity to politicise this referendum. By focusing on defeating Key himself and criticising the integrity of the process at every stage, the public was split along political party lines and it devolved into a referendum on Key, with many voting for the current flag as a protest vote against him.[65][49][66][12][61][67] For example, according to a January 2016 poll by UMR, 16% of those sampled said that they planned to vote to "send a message to John Key".[68] Key's inclusion of the Red Peak design in the shortlist at the request of the Green Party was seen as a belated and futile appeasement, and cross-party support was necessary from the very beginning of the process.[62][63][60]

Timing[edit]

Members of parliament were also concerned about the timing. Some expressed disgust at the timing of the bill just before the centenary of the Gallipoli landing, some said the process was rushed, and Louisa Wall said that no significant event had occurred to warrant a flag change at this time.[58] Others said it was more important to become a republic before considering whether to remove a symbol of British rule from the flag.[69][56][12][62][70] Political commentators also suggested that the timing was futile. Matthew Hooton pointed out that there would have been sufficient national momentum in the aftermath of the 2011 Rugby World Cup instead.[59] Morgan Godfery suggested that the public kept the current flag due to insecurity about cultural identity at a time when familiar cultural touchstones like house ownership, the dairy industry and demographics were undergoing upheaval.[71] Audrey Young suggested that the process was too rushed, and a longer one lasting at least two electoral cycles would have allowed more time for opposition party support and the possibility of a Labour prime minister overseeing the final result.[62] Martin Kettle cited status quo bias as a critical influence in referendums and noted that change is typically only possible if there is a previously existing, firm, well-informed movement for change.[72]

Priority[edit]

Opposition parties condemned the flag as low priority compared to current issues in the public consciousness such as education, health and housing. Trevor Mallard and Phil Goff cited the results of recent opinion polls that showed public opposition or apathy to a flag change.[58]

Cost[edit]

Opposition parties, Royal New Zealand Returned and Services' Association (RSA) president Barry Clark and members of the public criticised the referendum plan for costing $26 million which could be spent on other issues.[73][74][75][59][76][77] The $4 million publicity campaign for the national tour was especially criticised as public turnout was markedly apathetic; some admitted that they attended just for free biscuits, and at the Christchurch event only ten people arrived.[70][78]

Key defended the cost of the referendum by stating that it was the price to ensure a genuine democratic process and would be a one-off cost for the next "50 to 100 years" regardless of the result.[79] David King pointed out that a stronger brand image for the country could lead to a net financial gain, especially through exports and tourism,[19] with Key pointing out the precedent of Canada changing to its current maple-leaf flag.[59]

Order of questions[edit]

During the first Parliamentary hearing, Labour Party, NZ First, Green Party and Māori Party expressed dissatisfaction with the order of the questions and said that the public should first be asked whether they want a change, and continue with a second referendum only if they do, or both questions compacted into one referendum, which could potentially save millions of dollars.[58][29] David Seymour (ACT's representative in the Cross-Party Group) said that the planned order made sense, as the public would need to see the alternative designs before deciding on a change.[80] Professor John Burrows, chair of the Flag Consideration Panel, agreed that familiarity with proposals was a prerequisite for a properly informed decision about them.[20]

Bias[edit]

Various members of parliament accused the process and documents of being biased. Trevor Mallard and Phil Goff claimed that the final list of members of the Flag Consideration Panel was numerically slanted towards those nominated by the National Party, despite the shortlist of candidates being roughly neutral. Denis O'Rourke said that the shortlisting process was undemocratic because the Flag Consideration Panel would select the final flag design options on behalf of New Zealanders. Stuart Nash presented quotes in the Regulatory Impact Statement document admitting that referendum options were restricted by prior decisions by the prime minister and National Party dominated Cabinet, accusing them of pre-determining the process.[58]

A third-party analysis of submissions to the consideration panel's StandFor.co.nz website revealed that negative submissions were filtered out and disregarded in the panel's report and the associated and widely publicised word cloud. According to this analysis, the largest term in the official word cloud, "equality", appeared in 4.89% of comments, whereas "keeping the current flag" was the most common theme and represented 31.96% of comments.[81] According to opposition MP Trevor Mallard this shows that the flag change process suffered from "total spin" and that the panel pushed to change the flag in breach of its mandate to be neutral.[9]

Documents revealed that Flag Consideration Panel judge Julie Christie was a board member of the New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (NZTE) body New Zealand Story where she "had formally agreed to support the use of the NZ Way Fern Mark in any flag design". This fern design ended up as one of the shortlist entries. Christie had declared this as a potential conflict of interest but it was dismissed as minor.[82]

After the Flag Consideration Panel revealed the four shortlisted designs, some noticed that three out of the four designs coincided with Prime Minister John Key's personal design preferences. (3/4 contained a silver fern until the Red Peak flag was added) Thus, the panel was accused of being sycophantic and undermining their mandate to be neutral and democratic, which restricted the options available to the public and ruined the reputation of the whole process.[83][84][85][11]

Flag solicitation and selection[edit]

The National Business Review criticised the use of crowdsourcing to solicit flag designs that became publicly viewable on the government's website.[49] Crowdsourcing processes have historically been inundated by unqualified participants submitting large numbers of very low-quality, plagiarised or malicious contributions that ignore standard rules and best practices, with a high administrative burden to identify which ones are legal and serviceable.[86] Crowdsourcing has especially proved unsuitable for tasks that require training or expertise. For example, in an expert review of hundreds of photographs submitted to the news site NU.nl, 86% of submissions were deemed unusable and only one photograph was considered professional quality.[86] In the case of the flag referendums, the flag solicitation process was treated as a joke by the public and garnered far too many amateurish and facetious proposals.[11] These were openly viewable on the government's website and became disseminated and mocked on worldwide media, threatening the prestige of the whole process.[49][59]

Commentators felt that the Flag Consideration Panel did not have the expertise to make any adequate flag design judgements, since none of its members had any credentials or experience in the fields of graphic design, art or vexillology.[51][87][88][89][48][90][91][92][83][85] A spokesman responded that "it was considered that panel members did not need specialist skills in art, design, legal or intellectual property" and that consultation with experts would be sufficient.[92] The panel stated that it consulted vexillologists and designers to ensure that the flags chosen were workable and had no impediments.[27] According to journalist Grant McLachlan, the panel consulted a Nike shoe designer and not any vexillologists.[84] Illustrator Toby Morris condemned the process as "design by committee" and noted that the structural issues were so obvious that he and other designers were able to predict the selections and outcome as soon as the process was announced.[11] Some commentators suggested that the flags should have been evaluated only by professional designers.[49][93] Nándor Tánczos opined that the Flag Consideration Panel denied the public a chance to choose their favourite designs by deciding on their behalf, since the public had no input or voting on the flag selection.[69]

Professionals have pointed out that the process ignored established best practices in the fields of market research, design and vexillology.[94] Missing elements included clear research questions, artistic criteria, requirements elicitation, prototyping, monetary reward, direct public consultation on the longlist and shortlist selections, design iteration, deadline extensions and consideration of choice architecture such as randomisation.[95][93][96][11][97] Those who criticised the use of crowdsourcing sometimes suggested that design professionals should have been given a core role in the creation of the flag designs.[49][56] For comparison, the North American Vexillological Association's accepted flag design process also involves soliciting public design suggestions, but these submissions are seen only by design experts and vexillologists who then evaluate the entries and make necessary refinements or make new designs based on the suggestions.[98]

The flag design shortlist was met with negative response from most members of the public, professional designers and the International Federation of Vexillological Associations,[88][90][84] with the selection labelled "a national disgrace" by writer Karl Puschmann[48] and "tea towels of Kiwiana" by Gareth Morgan.[83] The selection was lambasted as unappealing, clichéd, dull, superficial and too logo-like. There were complaints that the four initial designs did not offer sufficient variety, as only one did not feature a large silver fern dividing the field, and two were identical except for a colour choice,[49] prompting accusations of groupthink and favouritism amongst the panel.[95][11] For critics of the referendum process, the problems with the design selection confirmed the ineptitude they had long suspected of the panel.[70] In hindsight, those analysing the reasons for the referendums' failure have posited that the quality of the official selection was so poor that it effectively prevented the possibility of a flag change.[69][49][99] Some proposed that the outcome reflected the public's negative reception of the Kyle Lockwood design more than their underlying attitudes about flag change or national identity.[71][94][56][70]

Inclusion of Red Peak flag[edit]

In September, the initial shortlist of four flags was amended to include the Red Peak flag after an online petition accrued 50,000 signatures. NZ First leader Winston Peters, former National Party official Grant McLachlan and others felt that instead of respectfully incorporating wider public opinion, this inclusion was an arbitrary deference to a trendy but unrepresentative social media campaign at the expense of established procedure and other, larger social media campaigns about the flag.[85] McLachlan demonstrated that online signatures could easily be forged by recording himself signing the petition sixteen times and fraudulently impersonating members of parliament. They accused the campaign of having dubious credibility and chided the government for considering the petition without checking the details sufficiently.[100]

First referendum[edit]

If the New Zealand flag changes, which flag would you prefer?[101]

- Option A

- Option B

- Option C

- Option D

- Option E

The first referendum started on 20 November 2015 with voting closing three weeks later on 11 December 2015. Using the preferential voting system,[102] it asked voters to rank the five shortlisted flag alternatives in order of preference. The most popular design would contend with the current national flag in the second referendum.[25][28][6][103][42]

Opponents of flag change encouraged members of the public to abstain from voting, render the voting paper invalid or strategically vote for the worst alternative flag as a protest.[104]

Results[edit]

Preliminary results were released on the night of 11 December; official results were declared on 15 December. Voters ranked Kyle Lockwood's Silver Fern (Black, White and Blue) design as the most preferred out of the five options.

| Option | First preference | Second iteration | Third iteration | Last iteration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | |

| 559,587 | 40.15 | 564,660 | 40.85 | 613,159 | 44.77 | 670,790 | 50.58 | |

| 580,241 | 41.64 | 584,442 | 42.28 | 607,070 | 44.33 | 655,466 | 49.42 | |

| 122,152 | 8.77 | 134,561 | 9.73 | 149,321 | 10.90 | — | ||

| 78,925 | 5.66 | 98,595 | 7.13 | — | ||||

| 52,710 | 3.78 | — | ||||||

| Total | 1,393,615 | 100.00 | 1,382,258 | 100.00 | 1,369,550 | 100.00 | 1,326,256 | 100.00 |

| Non-transferable votes | 11,357 | 0.73 | 24,065 | 1.56 | 67,359 | 4.35 | ||

| Informal votes | 149,747 | 9.68 | ||||||

| Invalid votes | 3,372 | 0.22 | ||||||

| Total votes cast | 1,546,734 | 100.00 | ||||||

| Turnout | 48.78 | |||||||

Non-transferable votes include voting papers that were not able to be transferred, as all of the preferences given had been exhausted. Informal votes include voting papers in which the voter had not clearly indicated their first preference. Invalid votes include voting papers that were unreadable or cancelled.

The added work of calculating results for individual electorates under preferential voting made no vote breakdown by electorate be available.

Second referendum[edit]

What is your choice for the New Zealand flag?[106]

- Option 1 (alternative design)

- Option 2 (existing design)

The second referendum started on 3 March 2016 with voting closing three weeks later on 24 March 2016. It asked voters to choose between the existing New Zealand flag and the preferred alternative design selected in the first referendum.[6][107]

Results[edit]

On 24 March 2016, the preliminary results of the second referendum were announced with the current flag winning 56.7% compared to 43.3% for the new flag.[108]

| Option | Votes | |

|---|---|---|

| Num. | % | |

| 921,876 | 43.27 | |

| 1,208,702 | 56.73 | |

| Total | 2,130,578 | 100.00 |

| Informal votes | 5,044 | 0.21 |

| Invalid votes | 5,273 | 0.23 |

| Total votes cast | 2,140,895 | 100.00 |

| Turnout | 67.78% | |

Informal votes include voting papers where the voter had not clearly indicated their preference (e.g. votes returned blank or voting for both options).

Invalid votes include voting papers that were unreadable or cancelled.

Results by electorate[edit]

Of New Zealand's 71 electorates, only six had a majority vote in favour of the alternative flag: Bay of Plenty, Clutha-Southland, East Coast Bays, Ilam, Selwyn, and Tāmaki.[109]

The Māori electorates had markedly low turnout and high support for the status quo. This result confused Malcolm Mulholland of the Flag Consideration Panel, who believed they had adequately engaged with Māori during their nationwide tour.[35]

| Electorate | Option 1 | Option 2 | Informal | Invalid | Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num. | % | Num | % | ||||

| Auckland Central | 9,466 | 43.37 | 12,359 | 56.63 | 75 | 91 | 60.95% |

| Bay of Plenty | 18,288 | 51.55 | 17,188 | 48.45 | 64 | 67 | 74.91% |

| Botany | 13,925 | 48.40 | 14,844 | 51.60 | 63 | 37 | 60.39% |

| Christchurch Central | 12,643 | 43.45 | 16,455 | 56.55 | 67 | 65 | 68.11% |

| Christchurch East | 12,269 | 41.80 | 17,080 | 58.20 | 46 | 54 | 69.83% |

| Clutha-Southland | 16,689 | 50.52 | 16,343 | 49.48 | 38 | 54 | 74.59% |

| Coromandel | 17,074 | 45.36 | 20,567 | 54.64 | 70 | 71 | 76.82% |

| Dunedin North | 10,077 | 35.74 | 18,121 | 64.26 | 101 | 61 | 65.93% |

| Dunedin South | 13,494 | 38.43 | 21,618 | 61.57 | 73 | 54 | 75.83% |

| East Coast | 14,108 | 42.40 | 19,163 | 57.60 | 66 | 71 | 70.90% |

| East Coast Bays | 15,422 | 51.17 | 14,714 | 48.83 | 57 | 63 | 68.44% |

| Epsom | 16,010 | 49.80 | 16,140 | 50.20 | 67 | 101 | 66.95% |

| Hamilton East | 14,035 | 48.00 | 15,202 | 52.00 | 79 | 48 | 64.64% |

| Hamilton West | 13,196 | 44.70 | 16,328 | 55.30 | 51 | 60 | 64.91% |

| Helensville | 13,860 | 43.35 | 18,115 | 56.65 | 63 | 63 | 73.14% |

| Hunua | 15,538 | 46.52 | 17,864 | 53.48 | 45 | 55 | 72.14% |

| Hutt South | 14,531 | 42.94 | 19,306 | 57.06 | 83 | 299 | 70.72% |

| Ilam | 16,226 | 50.85 | 15,684 | 49.15 | 60 | 77 | 72.50% |

| Invercargill | 12,992 | 39.96 | 19,521 | 60.04 | 48 | 47 | 72.42% |

| Kaikoura | 16,979 | 46.93 | 19,204 | 53.07 | 83 | 48 | 77.46% |

| Kelston | 8,450 | 35.03 | 15,673 | 64.97 | 60 | 66 | 57.89% |

| Mana | 13,207 | 43.23 | 17,341 | 56.77 | 84 | 67 | 66.92% |

| Māngere | 5,054 | 29.00 | 12,375 | 71.00 | 57 | 54 | 42.39% |

| Manukau East | 5,337 | 32.39 | 11,142 | 67.61 | 58 | 31 | 41.31% |

| Manurewa | 6,308 | 34.39 | 12,032 | 65.61 | 66 | 45 | 45.19% |

| Maungakiekie | 10,970 | 40.89 | 15,861 | 59.11 | 67 | 75 | 58.95% |

| Mount Albert | 11,144 | 38.48 | 17,815 | 61.52 | 88 | 73 | 63.13% |

| Mount Roskill | 11,240 | 41.58 | 15,795 | 58.42 | 71 | 65 | 59.09% |

| Napier | 14,452 | 41.75 | 20,165 | 58.25 | 87 | 94 | 75.60% |

| Nelson | 17,185 | 47.96 | 18,648 | 52.04 | 111 | 80 | 74.09% |

| New Lynn | 10,664 | 39.50 | 16,335 | 60.50 | 63 | 68 | 60.48% |

| New Plymouth | 17,342 | 49.18 | 17,921 | 50.82 | 77 | 81 | 72.48% |

| North Shore | 17,361 | 49.50 | 17,714 | 50.50 | 74 | 91 | 71.42% |

| Northcote | 13,362 | 43.72 | 17,202 | 56.28 | 86 | 52 | 66.00% |

| Northland | 13,433 | 39.18 | 20,848 | 60.82 | 89 | 97 | 74.12% |

| Ōhāriu | 15,055 | 46.01 | 17,669 | 53.99 | 79 | 102 | 72.79% |

| Ōtaki | 15,316 | 42.45 | 20,768 | 57.55 | 79 | 63 | 76.98% |

| Pakuranga | 14,409 | 46.78 | 16,391 | 53.22 | 59 | 59 | 66.76% |

| Palmerston North | 12,505 | 41.96 | 17,295 | 58.04 | 67 | 77 | 69.48% |

| Papakura | 12,175 | 40.95 | 17,557 | 59.05 | 42 | 67 | 63.61% |

| Port Hills | 16,709 | 45.91 | 19,689 | 54.09 | 99 | 61 | 74.84% |

| Rangitata | 17,095 | 48.27 | 18,322 | 51.73 | 57 | 39 | 75.74% |

| Rangitīkei | 14,672 | 43.95 | 18,710 | 56.05 | 42 | 71 | 76.95% |

| Rimutaka | 13,016 | 40.11 | 19,438 | 59.89 | 74 | 63 | 69.77% |

| Rodney | 18,070 | 47.45 | 20,009 | 52.55 | 86 | 56 | 76.47% |

| Rongotai | 11,382 | 37.20 | 19,215 | 62.80 | 124 | 121 | 66.52% |

| Rotorua | 13,428 | 43.67 | 17,324 | 56.33 | 65 | 62 | 70.82% |

| Selwyn | 18,604 | 51.73 | 17,361 | 48.27 | 61 | 45 | 79.43% |

| Tāmaki | 16,992 | 51.98 | 15,697 | 48.02 | 75 | 82 | 71.40% |

| Taranaki-King Country | 15,477 | 48.11 | 16,692 | 51.89 | 59 | 98 | 75.22% |

| Taupō | 16,312 | 46.96 | 18,421 | 53.04 | 73 | 47 | 73.78% |

| Tauranga | 17,554 | 49.82 | 17,683 | 50.18 | 76 | 64 | 73.79% |

| Te Atatū | 10,280 | 37.98 | 16,789 | 62.02 | 70 | 46 | 61.06% |

| Tukituki | 14,486 | 43.34 | 18,939 | 56.66 | 63 | 70 | 72.93% |

| Upper Harbour | 12,621 | 44.12 | 15,984 | 55.88 | 55 | 59 | 62.86% |

| Waikato | 16,570 | 47.72 | 18,150 | 52.28 | 59 | 63 | 74.81% |

| Waimakariri | 17,337 | 48.94 | 18,085 | 51.06 | 58 | 40 | 78.14% |

| Wairarapa | 15,306 | 43.16 | 20,159 | 56.84 | 88 | 66 | 75.50% |

| Waitaki | 19,092 | 49.52 | 19,462 | 50.48 | 85 | 36 | 77.95% |

| Wellington Central | 12,124 | 41.05 | 17,410 | 58.95 | 144 | 136 | 65.27% |

| West Coast-Tasman | 14,158 | 41.96 | 19,582 | 58.04 | 101 | 53 | 75.17% |

| Whanganui | 13,761 | 40.90 | 19,888 | 59.10 | 61 | 71 | 73.01% |

| Whangarei | 14,671 | 41.38 | 20,781 | 58.62 | 67 | 55 | 73.81% |

| Wigram | 11,679 | 43.03 | 15,465 | 56.97 | 56 | 67 | 67.88% |

| Hauraki-Waikato | 3,996 | 25.50 | 11,672 | 74.50 | 54 | 72 | 45.70% |

| Ikaroa-Rāwhiti | 3,817 | 22.72 | 12,985 | 77.28 | 76 | 125 | 49.01% |

| Tāmaki Makaurau | 3,396 | 22.11 | 11,967 | 77.89 | 68 | 100 | 44.80% |

| Te Tai Hauāuru | 4,190 | 26.02 | 11,912 | 73.98 | 81 | 80 | 50.04% |

| Te Tai Tokerau | 3,755 | 21.19 | 13,966 | 78.81 | 84 | 100 | 51.24% |

| Te Tai Tonga | 5,479 | 31.95 | 11,667 | 68.05 | 55 | 73 | 51.15% |

| Waiariki | 4,056 | 23.90 | 12,915 | 76.10 | 65 | 64 | 48.67% |

| Not identifiable | – | – | – | – | – | 195 | – |

| Total | 921,876 | 43.27 | 1,208,702 | 56.73 | 5,044 | 5,273 | 67.78% |

Multiple voting reports[edit]

After the first referendum, the Electoral Commission referred seven cases of people apparently voting more than once to police.[110]

On 8 and 9 March, the Electoral Commission referred four more cases of apparent multiple voting to police. This included one case of an Auckland man allegedly voting with 300 ballot papers stolen from other people's mailboxes.[111]

Voting more than once is known as personation and is identified as a corrupt electoral practice under both the Electoral Act 1993 and the Flag Referendums Act. A person convicted of personation is liable to up to two years' imprisonment and a fine up to $40,000, and carries a mandatory disqualification from enrolling or voting for three years.[112]

Aftermath[edit]

Reaction to results[edit]

John Key said that he was disappointed by the result but was still glad that the country had a valuable discussion about what it stood for.[71] The failure of the referendum resulted in a loss of political prestige for Key.[71] Some predicted that this failure would become part of his legacy, though others suggested that this would still be overshadowed by events such as the 2011 Christchurch earthquake and privatisation of state assets.[113][63]

Retrospectives from key figures[edit]

Years after the referendum, former Prime Minister John Key said his biggest regret was being unable to change the flag. He still believed the country should adopt a unique flag design to increase its sense of national pride, pointing out how proud Americans are of their national flag. He also believed that as a small country, New Zealand still needs "a symbol that is ours" to raise its profile and make its identity more well-known overseas. In hindsight, he blamed opposition parties for politicising the referendum and turning it a vote on him personally. If he could go back in time, he would have "pushed harder" and changed the flag without a referendum, as the public would become accustomed to a new design after it became official.[114][115][116]

Flag Consideration Panel member Malcolm Mulholland said he wasn't sure if the Lockwood flag designs were the best selections for the referendum. According to Mulholland, the Lockwood flags were chosen as compromise designs that were "a bob each way", as they combined the silver fern with elements from the current flag to appeal to people who were indecisive about flag change. In hindsight, he would have chosen a purely silver fern based design, as he observed the public warming up to a flag change later in the debate.[117]

Former Attorney-General Chris Finlayson (who was Attorney-General and a minister in John Key's government) commented in his memoir of the John Key years that "I think that New Zealand's flag is out of date and boring, and that we need to make a change but, thanks to the antics of the opposition parties I don't think this will be achieved for many years. I also think simplicity is the answer – everyone, for example, knows the French flag and (because of Russia's invasion) the Ukraine flag. The options that were devised for a new flag were too complex, and I think that could have been part of the reason why the referendum was defeated."[118]

Future prospects for change[edit]

Although the current flag was retained after the referendum, proponents of a flag change were still optimistic. Change the NZ Flag campaign leader Lewis Holden opined that the flag debate "has only just begun". He pointed out that support for the alternative design (43%) was a much closer result than anyone had expected, undermining the stature of the current flag and raising the possibility of a successful flag change in the future. He also noted that factors behind support for a flag change (i.e. cultural diversity, Asia-Pacific links and independent symbols) would only increase in the future.[119] Change the NZ Flag wound up and its web domain and Facebook page were taken over by New Zealand Republic. Former Green MP Keith Locke also pointed out that the 43% result was a marked increase over previous opinion polls that showed support for change in the 20–30% range. He suggested that a flag process with a better design and less politicisation could feasibly result in a majority vote for change.[120]

Politicians were not expected to revisit the flag issue for the next fifteen years or so, though becoming a republic may provide the impetus for another attempt at change.[71] Labour leader Andrew Little agreed that it was appropriate to discuss the flag as part of constitutional debates once the reign of Queen Elizabeth II was over.[121]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Second Referendum on the New Zealand Flag Preliminary Result". Electoral Commission. 24 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Process at a glance" (PDF). beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b Jones, Nicholas (9 March 2015). "Govt budget allows almost $500,000 for a high-profile panel out of $25m cost to decide national symbol". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Referendums on the New Zealand flag". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ a b c "First steps taken towards flag referendum". beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Flag design gallery". govt.nz. New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill, Part 2, Subpart 4, Clause 20". legislation.govt.nz. New Zealand government. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b Trevett, Claire (18 July 2015). "Flag show at half mast". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Nippert, Matt (13 November 2015). "Flag process: Was it a spin job?". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Price, Sam (29 December 2015). "Widespread abstention in New Zealand flag referendum". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Morris, Toby (25 March 2016). "Flag failure: Where did it go wrong?". rnz.co.nz. Radio NZ. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Bryce (29 March 2016). "Political roundup: The 20 best analyses of the flag referendum result". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Davison, Isaac (30 January 2014). "Key suggests vote on New Zealand flag". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Flag change in the wind". Radio New Zealand News. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Beech, James (4 February 2014). "Opinions vary on changing NZ flag". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Chapman, Paul (11 March 2014). "New Zealand to hold referendum on changing to 'post-colonial' flag". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill, sec. 2

- ^ New Zealand Flag Referendums Act 2015, sec. 39

- ^ a b c d King, David, Regulatory Impact Statement: Considering Changing the New Zealand Flag, New Zealand Ministry of Justice

- ^ a b "Flag Consideration Panel answers the six top questions". scoop.co.nz. Scoop Media. 6 June 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill – amendments". Parliamentary Counsel Office. 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions" (PDF). beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill, Part 3, Clause 70". legislation.govt.nz. New Zealand government. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "§58 National colours and other flags – Ship Registration Act 1992". legislation.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 July 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ a b Bill English (29 October 2014). "Cabinet Paper 451" (PDF). beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b Gulliver, Aimee (17 November 2014). "Flag referendum a 'distraction'". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Open letter from the Panel". New Zealand Government (Govt.nz). 17 December 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ a b Trevett, Claire (26 February 2015). "Julie Christie and Beatrice Faumina to help decide NZ's new flag". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b Trevett, Claire (12 March 2015). "Flag change referendums come one step closer". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Jones, Nicholas (13 April 2015). "NZ First backs 'fight for the flag' campaign". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Flag debate votes a biased process – Mallard". The New Zealand Herald. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill — In Committee". parliament.nz. New Zealand House of Representatives. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "All Suggested Designs". The New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ a b c "The Panel's report to the Responsible Minister | NZ Government". Govt.nz. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ a b Young, Audrey (28 March 2016). "Maori flag attitudes a puzzler". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Young, Audrey (11 August 2015). "Forty flags, and only one with a Union Jack—so which one is best?". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Morgan Foundation Flag Competition Judging Results". designmyflag.nz. Gareth Morgan Foundation. 24 July 2015. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Hunt, Elle (1 September 2015). "New Zealand's new flag: final four designs announced". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (1 September 2015). "NZ flag referendum: The final four designs revealed". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Simpson, Rowan (2 September 2015). "Dear John".

- ^ "Flag referendum: Red Peak design to be added as fifth option – John Key – National – NZ Herald News". The New Zealand Herald. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Various (1 September 2015). "Four alternatives" (PDF). govt.nz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Masterbrand Guidelines and Specifications" (PDF). July 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Silver Fern (Red, White and Blue)". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "Press & television coverage featuring our flag from NZ and around the world". Silverfernflag.co.nz. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "How about a bungee-jumping sheep? John Oliver mocks NZ flag". The New Zealand Herald. New Zealand Media and Entertainment. 4 November 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Lush, Martin (6 June 2014). "Winning design of new NZ flag contest slammed". radiolive.co.nz. Radio Live. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Puschmann, Karl (1 September 2015). "Flag designs a national disgrace". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Five reasons the flag-change campaign failed". The National Business Review. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Flag critiqued for similarities to political parties' logos". The New Zealand Herald. New Zealand Media and Entertainment. 2 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ a b Cooke, Henry; Fyers, Andy (1 September 2015). "What Twitter said about the final four New Zealand flag options". Stuff (company). Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Town, Chris. "Why the Koru flag is the 'best of the bunch'". Stuff. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ "Red Peak by Aaron Dustin". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ "New Zealanders offered flag shortlist ask: can we have this one instead?". The Guardian. 4 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Flag referendum: Red Peak design to be added as fifth option – John Key". The New Zealand Herald. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "How the world saw NZ's flag decision". Radio NZ. 26 March 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Garner, Duncan (24 March 2016). "Duncan Garner: The flagging fortunes of a leader chasing a legacy". Stuff (company).

- ^ a b c d e "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill — First Reading". parliament.nz. New Zealand Parliament. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Hunt, Elle (10 August 2015). "New Zealand's prime minister John Key wants a new flag. Does anybody else?". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Finlay (26 March 2016). "Flag 'debate' always lacked substance". rnz.co.nz. Radio New Zealand.

- ^ a b Young, Audrey (25 March 2016). "Audrey Young: John Key a loser on flag referendum but not a failure". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ a b c d Young, Audrey (26 March 2016). "Audrey Young: Lessons to learn from flag vote". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ a b c Watkins, Tracy (26 March 2016). "Political week: John Key's top five regrets on the flag". Stuff (company).

- ^ "Change the NZ Flag launches campaign". Change the NZ Flag. 4 May 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ du Fresne, Karl (20 March 2016). "I barely recognise my fellow New Zealanders". blogspot.co.nz.

- ^ "'Wasteful vanity project' and 'starry-eyed sheep' – How world reacted to flag result". The New Zealand Herald. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Trotter, Chris (28 March 2016). "Chris Trotter: Whoops and cheers for democracy's flag". Stuff (company).

- ^ "Current flag still preferred – poll". The New Zealand Herald. 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Tánczos, Nándor (2 September 2015). "Getting our flag off a weetbix box". Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Manhire, Toby (24 March 2016). "In New Zealand, the flag remains the same. And so does everything else". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e Hunt, Elle (25 March 2016). "Ten months, 10,000 designs, no new flag for New Zealand. What was that about?". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Kettle, Martin (24 March 2016). "New Zealand's decision on the flag has lessons for Britain's EU referendum". The Guardian.

- ^ Garner, Duncan (9 May 2015). "Duncan Garner: Flag this irrelevant debate and spend $26m on hungry kids". The Dominion Post. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Thorne, Dylan (10 March 2015). "Editorial: $25.7m flag is wrong legacy". NZME Publishing Limited. Bay of Plenty Times. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand considers options to replace its flag". Al Jazeera. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "New Zealanders to vote on changing Union Jack-style flag". Luxemburger Wort. 29 October 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Cook, Frances; McQuillan, Laura (30 October 2014). "MPs torn on flag referendum". yahoo.co.nz. Newstalk ZB. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Campbell, John (19 May 2015). "Does New Zealand care about a new flag?". 3news.co.nz. TV3. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Bennett, Adam (30 October 2014). "Taxpayers face $25 million bill even if old flag stays". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (12 March 2015). "Labour to oppose flag bill". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Tutty, Caleb (13 November 2015). "The Flag Debate". Herald Insights. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Fisher, David (11 September 2015). "Flag judge Julie Christie's conflicts of interest". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Morgan, Gareth (7 September 2015). "Gareth Morgan: Back up the flag bus now". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ a b c McLachlan, Grant (10 September 2015). "Grant McLachlan: Flag debate now a political turf war". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ a b c NZ Flag Institute (4 March 2016). "Flawed Referendum Process on changing New Zealand's Flag". scoop.co.nz. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b Borst, Irma. "The Case For and Against Crowdsourcing: Part 2". Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "'Which bad flag design will the rest of the world ignore from now on' – Aussies". tvnz.co.nz. TVNZ. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b "'Lol...even laser beam kiwi would be better' – social media reacts to flag semi-finalists". tvnz.co.nz. TVNZ. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand announces shortlist for new flag design". Yahoo!. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b "New Zealand announces shortlist for new flag design". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Manhire, Toby (4 September 2015). "Toby Manhire: Let's run up the red flag". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ a b Story, Mark (3 September 2015). "Renowned designer slams flag process". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b Lusk, Chris (29 March 2016). "How to get the flag referendum right next time". Stuff (company). Stuff. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b Neal, Geoff (21 March 2016). "The missing vote in New Zealand's flag referendum". Stuff. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b Neal, Geoff (25 March 2016). "12 things the flag process got very wrong". Stuff. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Smythe, Michael (11 March 2015). "Questions for the Flag Consideration Panel". Design Assembly. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016.

- ^ Farrar, David (24 March 2016). "Why the flag vote was for the status quo". kiwiblog.co.nz.

- ^ Kaye, Ted (November 2009). "Redesigning the Oregon State Flag: A Case Study" (PDF). Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Was the New Zealand flag vote completely futile? – video". The Guardian. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Fisher, David (26 September 2015). "Red Peak petition 'conned'". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill – Schedule 1". legislation.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Referendums on the New Zealand Flag > Voting in the first referendum > How Preferential Voting works". elections.org.nz. New Zealand Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ "Process to consider changing New Zealand flag" (PDF). beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (2 September 2015). "Revealed: Plots to gerrymander flag referendum". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ "First Referendum on the New Zealand Flag – Final Results by Count Report". Electoral Commission. 15 December 2015. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill – Schedule 2". legislation.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Flag Referendums Bill, Part 2, Subpart 4, Clause 20". legislation.govt.nz. New Zealand government. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand votes to keep flag in referendum". BBC News. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Final Result by Electorate for the Second Referendum on the New Zealand Flag, on the question "What is your choice for the New Zealand Flag"". Electoral Commission. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Flag voting double ups flagged". Radio New Zealand. 29 December 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Alleged flag voting paper theft investigated". Radio New Zealand. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Flag Referendums Act 2015, §59 and Electoral Act 1993, §224

- ^ Garner, Duncan (24 March 2016). "Duncan Garner: The flagging fortunes of a leader chasing a legacy".

- ^ "Sir John Key says if he could redo anything from his time as PM he would change the flag without consultation". 1 News. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Sir John Key reveals his biggest regret". newstalkzb.co.nz. Newstalk ZB. 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Driving force". 66magazine.co.nz. 66 Magazine. n.d.

- ^ "Expert feature: Flags". rnz.co.nz. Radio New Zealand. 2 August 2021.

- ^ Finlayson, Chris (2022). Yes, Minister – an insider's account of the John Key years. Allen & Unwin. p. 80. ISBN 9781991006103.

- ^ Holden, Lewis (25 March 2016). "This flag debate has only just begun". rnz.co.nz. Radio NZ.

- ^ Locke, Keith (26 March 2016). "Not a bad result for opponents of the colonial flag". thedailyblog.co.nz. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Hassan, Mohamed (26 March 2016). "Time to say goodbye to the monarchy?". rnz.co.nz. Radio NZ. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

External links[edit]

- Official referendum and flag submission website (archived 18 April 2016)

![Wā kāinga / Home by Studio Alexander [note 1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/NZ_flag_design_Wa_kainga_Home_by_Studio_Alexander.svg/120px-NZ_flag_design_Wa_kainga_Home_by_Studio_Alexander.svg.png)

![Modern Hundertwasser koru by Tomas Cottle [note 2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/NZ_flag_design_Modern_Hundertwasser_by_Tomas_Cottle.svg/120px-NZ_flag_design_Modern_Hundertwasser_by_Tomas_Cottle.svg.png)