191st Rifle Division

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| 191st Rifle Division (April 5, 1941 - July 1945) | |

|---|---|

Monument to soldiers of the 191st Rifle Division on the bank of the Voronka River in the village of Kernovo. Photo by Boris Yeremeev, 1967. | |

| Active | 1941–1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Red Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Leningrad strategic defensive Siege of Leningrad Tikhvin offensive Battle of Lyuban Sinyavino offensive (1942) Operation Iskra Leningrad–Novgorod offensive Battle of Narva (1944) Baltic offensive Tartu offensive Riga offensive (1944) Vistula–Oder offensive East Prussian offensive East Pomeranian offensive Battle of Berlin |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Novgorod |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Dmitrii Akimovich Lukyanov Maj. Gen. Timofei Vasilevich Lebedev Col. Nikolai Petrovich Korkin Lt. Col. Nikolai Ivanovich Artemenko Col. Pavel Andreevich Potapov Maj. Gen. Ivan Nikolaevich Burakovskii Maj. Gen. Grigorii Osipovich Lyaskin |

The 191st Rifle Division was an infantry division of the Red Army, originally formed as part of the prewar buildup of forces, based on the shtat (table of organization and equipment) of September 13, 1939. It began forming just months before the German invasion at Leningrad. At the outbreak of the war it was still not complete and was briefly held in reserve before being sent south to take up positions as part of the Luga Operational Group. After defending along the Kingisepp axis it was forced to withdraw in late August as part of 8th Army, and helped to establish the Oranienbaum Bridgehead. In October it was ferried into Leningrad itself, but was soon airlifted to 4th Army, which was defending against a German drive on Tikhvin. Although the town fell in November, within a week a counterstroke was begun against the vastly overextended German force, which was forced to evacuate on December 8. As it pursued to the Volkhov River the 191st was awarded the Order of the Red Banner, one of the first divisions so honored during the war. During the Lyuban Offensive it penetrated deep into the German lines as part of 2nd Shock Army, but was cut off, and only fragments of the division emerged from the encirclement in early June, 1942. In September it was committed from reserve in an effort to sustain the Second Sinyavino Offensive, but this failed and the division was again encircled and forced to break out at considerable cost. During Operation Iskra in January, 1943 the 191st played a secondary role in reestablishing land communications with Leningrad, partially raising the siege. The division was relatively inactive as part of 59th Army along the Volkhov during the remainder of the year, but in January, 1944 it took part in the offensive that finally drove Army Group North away from Leningrad and received a battle honor for its role in the liberation of Novgorod. As the offensive continued the division advanced as far as Narva, where it was held up for several months. In late July, it staged an assault crossing of the river and helped take the city, for which one of its regiments also gained a battle honor. Following this victory the 191st advanced into Estonia, gradually moving toward the Latvian capital of Riga. Once this city was taken the division was moved south, and by the start of the Vistula–Oder offensive in January, 1945 it was part of 50th Army in 2nd Belorussian Front, but it was soon reassigned to 49th Army, where it remained for the duration. During the East Pomeranian operation it advanced on Gdańsk, and two of its regiments would later receive decorations for their roles in the campaign. During the final campaign into central Germany the 191st crossed the Oder River before pushing northwest into Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; several of its subunits would receive decorations as a result of this fighting in the final days. The division had a fine record of service that encompassed most of the struggle for Leningrad, but it would be disbanded in July.

Formation[edit]

The division began forming on April 5, 1941, as part of the prewar buildup of Soviet forces, at Leningrad in the Leningrad Military District. Its order of battle on June 22 was as follows, although it changed in several respects during the war:

- 546th Rifle Regiment

- 552nd Rifle Regiment

- 559th Rifle Regiment

- 484th Light Artillery Regiment (later 1081st Artillery Regiment)

- 504th Howitzer Artillery Regiment (until October 16, 1941)[1]

- 8th Antitank Battalion

- 253rd Reconnaissance Battalion (later 253rd Reconnaissance Company)

- 330th Sapper Battalion

- 554th Signal Battalion (later 54th Signal Company)

- 15th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 176th Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company

- 237th Motor Transport Company (later 293rd Motor Transport Battalion)

- 82nd Field Bakery (later 343rd Motorized Field Bakery, 268th Field Bakery)

- 152nd Divisional Veterinary Hospital (later 491st)

- 72417th Field Postal Station (later 726th, 29165th)

- 556th Field Office of the State Bank

Col. Dmitrii Akimovich Lukyanov took command the day the division started forming. This officer had served as a regimental commander in the 45th Rifle Division during the Winter War, being awarded the Order of the Red Banner, and later rose to the position of the division's deputy commander.

Defense of Leningrad[edit]

At the outbreak of war with Germany the 191st was in the reserves of Leningrad Military District (redesignated as Northern Front on June 24), along with the 177th Rifle Division, 8th Rifle Brigade, and several fortified regions.[2] The division was still in the process of being completed at this time.[3] The District commander, Lt. Gen. M. M. Popov, had prepared a defense plan on May 25 which proposed the formation of five "covering regions", each manned by the forces of its own Army. Under this plan, as originally formulated, the 191st and 177th, plus the 70th Rifle Division and most of 1st Mechanized Corps, were retained as Popov's reserve, although these additional forces had been reassigned by the outbreak of the war.[4]

After its breakneck advance through the Baltic states, Army Group North began moving again early on July 9 from the Pskov and Ostrov regions. It was now 250km from Leningrad. In anticipation, on July 4 Army Gen. G. K. Zhukov ordered Popov to "immediately occupy a defense line along the Narva–Luga–Staraya Russa–Borovichi front." Popov officially formed the Luga Operational Group on July 6,[5] and as of July 10 it consisted of the 191st and 177th Divisions as well as the 1st Narodnoe Opolcheniye Division and four machine gun-artillery battalions.[6]

By July 14 the Group had been considerably reinforced with the 41st Rifle Corps, 1st Mountain Rifle Brigade, two more Opolcheniye divisions, and other forces. Popov also placed the two tank divisions of 10th Mechanized Corps in Front reserve to provide armor support. The construction of the actual defense line had begun on June 29, using construction workers and civilians from Leningrad, although when the 177th Division arrived south of Luga itself on July 4 it was so incomplete that an additional 25,000 labourers had to mobilized. The 191st occupied the Kingisepp sector of the line. Meanwhile, the German advance from Pskov, while slower than through the Baltics due to rugged terrain and summer heat, was still gaining some 25km per day. The XXXXI Panzer Corps advanced on Kingisepp, and on July 13 a combat group of 6th Panzer Division captured a small bridgehead over the Luga River. After securing additional footholds southeast of Kingisepp the panzers' advance was stalled for six days by fanatical Soviet resistance.[7]

In response to a letter from the STAVKA dated July 15, Popov split the Luga Group into three separate and semi-independent sector commands on July 23. The Kingisepp Sector, under command of Maj. Gen. V. V. Semashko, consisted of the 191st and 90th Rifle Divisions, two Opolcheniye divisions, and several other assets. On the same day, Hitler reiterated his goal of taking Leningrad before marching on Moscow. Beginning on August 8, the Northern Group of Army Group North was to attack from the Poreche and Sabsk bridgeheads over the Luga, through Kingisepp toward Leningrad. On August 11, after three days of heavy fighting which cost the attackers 1,600 casualties, the XXXXI Panzers and XXXVIII Army Corps were able to penetrate the defenses of 90th Rifle and 2nd Opolcheniye Divisions along the Luga at Kingisepp, Ivanovskoe, and Bolshoi Sabsk. The 8th Panzer Division was now committed, which cut the Kingisepp–Krasnogvardeisk rail line the next day. Kingisepp itself fell on August 16. Most of the defenders fell back to the Krasnogvardeisk Fortified Region, but by now the 191st had been transferred to 8th Army, and it, plus the five other worn-down divisions of that Army threatened the left flank of XXXXI Panzers, forcing it to suspend its attacks on Krasnogvardeisk.[8]

Oranienbaum Bridgehead[edit]

To resolve this situation, the German 18th Army's XXVI and XXVIII Army Corps attacked northward toward the Gulf of Finland between August 22-25. By September 1, 8th Army had been forced back to new defenses in a tight bridgehead south of Oranienbaum, which would be held by Soviet forces until 1944. The assault left 8th Army in a shambles. The Army commander reported to Popov on August 25 that "[t]he main danger now in the command and control of units is the absence of almost 100 percent of our regimental commanders and their chiefs of staff and battalion commanders."[9]

Leningrad was cut off on September 8. Meanwhile, 8th Army defended the bridgehead with the 191st, 118th, 11th, and 281st Rifle Divisions, facing XXXVIII Corps. The attack began on September 9. According to A. V. Burov's war diary, "Battle is also raging south of Kolpino and along the Oranienbaum axis." The 191st was facing the 291st Infantry Division west of Ropsha. The division was pushed northwest of that place, but managed to hold there. General Zhukov had arrived at Leningrad on September 9, and his deputy, Maj. Gen. I. I. Fedyuninskii, soon reported that the morale of 8th Army, as well as the 42nd and 55th Armies, was cracking. On September 14, Zhukov decided to go over to the attack, as he perceived that the German advance to Uritsk had left them vulnerable to a flank attack; 8th Army would act as the "hammer" and 42nd Army as the "anvil". The 191st and 281st Divisions, reinforced by the 11th and 10th Rifle Divisions plus what remained of the 3rd Opolcheniye Division would attack toward Krasnoye Selo. The commander of 8th Army, Maj. Gen. V. I. Shcherbakov, declared his forces were too weak to carry out this plan, and he was relieved of his command. Lt. Gen. T. I. Shevaldin replaced him.[10]

In the event, the German forces preempted 8th Army's counterattack, by resuming their own offensive on September 16. This encountered strong and continuing Soviet resistance and heavy fighting went on for possession of Volodarsky, Uritsk, and Pulkovo Heights until the end of the month, by which time 42nd Army had solidified its defenses. However, to the west three German divisions, including 1st Panzer, attacked and defeated 10th Rifle and forced it to abandon Volodarsky on September 16. The attackers reached the Gulf of Finland the same day, cutting the Oranienbaum bridgehead off from Leningrad, which was in turn cut off from the rest of the USSR. Whipped on by Zhukov, Shevaldin completed his regrouping on September 18 and attacked toward Krasnoye Selo with four divisions the next day. A further German assault struck on September 20, forcing the 191st and the remainder of Shevaldin's shock group back to the line Novyi Petergof–Tomuzi–Petrovskaya, where the front stabilized once and for all.[11]

First Sinyavino Offensive[edit]

In early October the 191st was removed from the bridgehead into Leningrad proper, where it was assigned to the Eastern Sector Operational Group, formed by Fedyuninskii from 55th Army and Front reserves. This Group consisted of five rifle divisions, two tank brigades and one battalion, and supporting artillery. It was intended to assault across the Neva River on a 5km-wide sector between Peski and Nevskaya Dubrovka, advance toward Sinyavino, and help encircle and destroy the German forces south of Shlisselburg in conjunction with 54th Army advancing from the east, effectively lifting the siege. Again, German action preempted the Soviet attack, as they began a thrust toward Tikhvin on October 16. Nevertheless, the STAVKA insisted that the attack proceed as planned on October 20, but it made little progress. By October 23, Tikhvin was directly threatened,[12] and at about this time the 191st was transferred to 4th Army, which was under direct STAVKA control.[13]

Battle for Tikhvin[edit]

The mission of Army Group North was exploit an apparent weakness of Soviet forces along the Volkhov River, attack through Tikhvin to Lake Ladoga to cut Leningrad's last tenuous rail links to Moscow, and possibly link up with the Finnish Army on the Svir River. To conduct the offensive, the XXXIX Motorized Corps and most of I Army Corps were concentrated at Kirishi, Lyuban, and southward along the Volkhov. By mid-October the 54th, 4th, and 52nd Armies, plus Northwestern Front's Novgorod Army Group, were attempting to defend a 200km front, with 4th Army conducting local operations along a 50km line from just west of Kirishi and southward along the Volkhov. The harsh terrain in the Tikhvin region would have a major impact on the upcoming operations, a vast forested and swampy territory crisscrossed with many rivers and streams. The deteriorating weather would also play a role.[14]

Early on October 16, the German 21st and 126th Infantry Divisions had stormed across the Volkhov, followed later in the day by the 12th Panzer and 20th Motorized Divisions. 4th Army's defenses were penetrated in four days of fighting in roadless terrain covered with 10cm of snow. On October 23 Budogoshch was taken, which convinced the STAVKA that 4th Army required reinforcement. The 191st was moved by air transport to Sitomlya, some 40km southwest of Tikhvin, to take up hastily-erected defenses, while the 44th Rifle Division was airlifted to Tikhvin itself as a backstop along the Syas River. The Army was also sent the 92nd Rifle and 60th Tank Divisions from the Reserve of the Supreme High Command.[15]

Once reinforced, the 4th and 52nd Armies should have been able to drive the German forces back to the Volkhov. However, their defenses continued to collapse due to committing reserves into battle in piecemeal fashion, without preparation, and with weak command and control. As an example, on October 27 the 191st, with elements of 4th Guards Rifle Division and 60th Tanks attacked the 12th Panzer's advance guard near Sitomlya. This effort failed because it was poorly coordinated (the 191st had only arrived over the previous two days), but it did force the panzers to halt their advance and regroup. Over the coming days the STAVKA began planning a series of counterstrokes which it hoped would end in the defeat of the German forces on the Tikhvin axis. 4th Army's commander was ordered to concentrate two shock groups, each of roughly two divisions, southwest of the town. The first group consisted of the 191st, one rifle regiment of the 44th and one regiment of 60th Tanks deployed in the vicinity of Sitomlya. The two groups were to attack on November 1 toward Budogoshch and Gruzino together with the 92nd Division already operating to the south, and eventually reestablish the Soviet positions along the Volkhov. The 191st actually began its attack on November 2, but it failed in the face of heavy German air and artillery strikes and strong counterattacks.[16] In the course of this fighting, Colonel Lukyanov was seriously wounded and evacuated to the rear. After being released from hospital in January 1942 he was given command of the 2nd Rifle Division and held several other commands during the remainder of the war, being promoted to the rank of major general on May 18, 1943. Col. Pavel Semyonovich Vinogradov took over the 191st on November 5.

On the same date, and despite further counterattacks, XXXIX Motorized resumed its advance, now reinforced with 8th Panzer and 18th Motorized Divisions. 12th Panzer shoved the 191st to one side on November 6 and, aided by a frigid blast of weather that began freezing rivers and streams, captured Tikhvin on November 8, cutting the last rail line from Moscow to Lake Ladoga. Despite this success, it was clear that the German force had "shot its bolt". Its vehicles and men had been severely weakened by Soviet resistance, the exceptional cold and the terrible terrain. Even before reaching the town, temperatures had dropped as low as -40 degrees and ill-equipped German soldiers were frostbitten or simply froze to death. Tikhvin was three-quarters encircled and there was no strength or will to continue driving northward. Hitler, however, refused to sanction any retreat.[17]

The Tikhvin Counterstroke[edit]

In late November the three Soviet Armies faced a total of 10 infantry divisions, two motorized and two panzer divisions deployed on a very lengthy front from Lake Ladoga to Tikhvin and then southwest to Lake Ilmen. All of these were reduced to about 60 percent strength and had a combined total of about 100 tanks and assault guns, plus about 1,000 artillery pieces. The STAVKA had concentrated 17 rifle divisions, two tank divisions, one cavalry division (also under strength to various degrees), plus other units, giving them a considerable superiority in infantry and guns, and a slight inferiority in armor. 4th Army, now under command of Army Gen. K. A. Meretskov, was divided into Northern, Eastern and Southern Operational Groups; the Eastern consisted of the 191st, one rifle regiment of the 44th Division, the 27th Cavalry Division, the 120th Regiment of 60th Tanks, plus the 128th Tank Battalion. The 191st faced 18th Motorized just south of the town; this division was trying to hold a strongpoint defense line along the long route XXXIX Corps had taken to Tikhvin. The Army's mission was to encircle the German forces in the town and destroy them, then to exploit toward Budogoshch, linking up with the two other Armies before taking bridgeheads over the Volkhov.[18]

It proved impossible to coordinate the start of such a wide-ranging offensive, and 4th Army's part began on November 19. 12th Panzer and 18th Motorized remained bottled up in Tikhvin on Hitler's orders, although the Soviet pressure on the strongpoint defense line, which had been reinforced with the 250th Infantry Division, required a constant drain on armor from the town. By December 7, the 12th Panzer and 18th Motorized were enveloped from three sides and suffering heavy losses fighting in deep snow and bitter cold. The 18th had lost 5,000 men and was reduced about 1,000 combat soldiers, on top of its losses in the advance. Meretskov's Southern Group was approaching Sitomlya, threatening communications from Tikhvin to the rear. At this time the Soviet counteroffensive west of Moscow was underway, which rendered Hitler's notions of continuing an advance from Tikhvin utterly futile. At 0200 hours on December 8 he finally authorized a withdrawal, which, in fact, had been underway for several hours. As this went on, the Northern and Eastern Groups struck the German rearguards and liberated Tikhvin late on December 9. While the mobile divisions withdrew in good order, the 61st Infantry Division's 151st Regiment, supported by two companies of 18th Motorized's 51st Regiment, attempted to block the pursuit and suffered catastrophic losses in the process.[19] The retaking of Tikhvin, in the event, would prove to be one of the first permanent liberations of Soviet territory during the war, and probably saved Leningrad. On December 17, the 191st would become one of the Red Army's first rifle divisions to be awarded the Order of the Red Banner for WWII service.[20]

Lyuban Offensive[edit]

By this time the forces of Army Group North were falling back to new defenses being erected along the Volkhov. Effective December 17 the STAVKA formed the new Volkhov Front, consisting of the 4th, 52nd, 59th and 26th (soon redesignated 2nd Shock) Armies. At 2000 hours a directive was issued which stated:

The Volkhov Front... will launch a general offensive to smash the enemy defending along the western bank of the Volkhov River and reach the Liuban' and Cholovo Station front with your armies, main forces by the end of [left blank]...

Subsequently, attacking to the northwest, encircle the enemy defending around Leningrad, destroy and capture him in cooperation with the Leningrad Front.[21]

The 191st would essentially remain in this Front until January 1944. On December 21, Colonel Vinogradov left the division to become chief of staff of 4th Army; he was replaced the next day by Maj. Gen. Timofei Vasilevich Lebedev. This officer had been commandant of the Moscow Infantry School in 1940-41, before taking command of the 235th Rifle Division prior to the war.

Expanding the Tikhvin counteroffensive into a Volkhov-Leningrad offensive of much greater scope first required the establishment of adequate bridgeheads. To Stalin's disgust, the armies of Volkhov Front (under command of Meretskov) did so too slowly. 4th Army reached the river near Kirishi and Gruzino on December 27 and seized lodgements, but only against determined resistance. Despite Stalin's urgings, 4th Army, now under Maj. Gen. P. A. Ivanov, was not able to capture Tigoda Station. Utterly exhausted, Meretskov's forces had no choice but to go over to the defense.[22]

On January 24, 1942, the 191st was transferred to 2nd Shock Army,[23] which was under command of Lt. Gen. N. K. Klykov. In the buildup to the renewed offensive the Army was ordered to form several operational groups in order to improve command and control over its greatly increased forces. The division was allocated to Operational Group Privalov, along with the 382nd Rifle Division and the 57th Ski Brigade. Its mission was to move the 191st and the 57th "through a penetration in the Lesopunkt region on the night of January 27 and advance through Olkhovka and Krevino to the Malaya Brontitsa, Chervino, and Ruchi regions as rapidly as possible."[24] On January 26, as he was leading elements of the division in a preliminary operation, General Lebedev was killed when his vehicle was blown up by an antitank mine. At the time, he was also serving as deputy chief of staff to 4th Army.[25] He was buried at Malaya Vishera, and was replaced the next day by Col. Aleksandr Ivanovich Starunin. This officer had previously served as chief of staff of the 311th Rifle Division before taking the same role in the 191st.

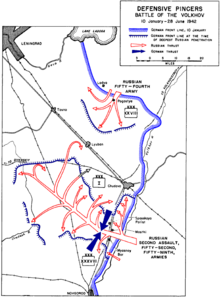

Beginning on January 6, 2nd Shock had made several efforts to break through the German defenses, and finally scored a partial success on January 17. With the support of over 1,500 aircraft sorties the Army finally penetrated the first German position on the Volkhov and advanced 5-10km. After a four-day halt to regroup, Klykov had resumed the fight on January 21, focused on the German strongpoints at Spasskaya Polist, Mostki, Zemtitsy, and Miasnoi Bor. On the night of January 23/24, Meretskov had finally convinced himself that 2nd Shock had blasted enough of a hole that he could commit his exploitation force, largely consisting of the 13th Cavalry Corps. However, after the cavalry and accompanying infantry passed through the gap, the XXXIX Motorized and XXXVIII Army Corps hastily assembled forces to contain the exploitation.[26]

Meretskov's renewed effort on January 27/28 again failed to take Spasskaya Polist and Zemtitsy due to weak cooperation, poor use of tanks and artillery, and costly frontal attacks. Nevertheless the bulk of 2nd Shock, including the 191st, was able to pass through the gap and advance up to 75km. There were now over 100,000 Red Army troops in the German rear in a position to advance on Lyuban. However, the frozen terrain of wooded swamps and peat bogs hindered the advance and the narrow gap imposed its own difficulties on communications.[27]

Battle in Encirclement[edit]

During February's fighting, Klykov's forces were able to expand their pocket but were unable to break out decisively toward Leningrad.[28] On February 21, Colonel Starunin was wounded in action; he was replaced on February 25 by Col. Nikolai Petrovich Korkin, who had previously led the 372nd Rifle Division and the 23rd Rifle Brigade. On February 26, an increasingly frustrated Stalin directed Meretskov as follows:

... the STAVKA categorically demands that, under no circumstances are you to cease the 2nd Shock and 59th Armies' offensive operations along the Liuban' and Chudovo axes in the expectation of reinforcements. On the contrary, it demands that, after receiving reinforcements, you reach the Liuban'-Chudovo railroad by 1 March in order to liquidate the enemy Liuban' and Chudovo groupings completely no later than 5 March.

Stalin also sent Lt. Gen. A. A. Vlasov to serve as Meretskov's deputy. A further attack by five rifle divisions, including the 191st, one cavalry division, and four rifle brigades on March 4 made only minor gains against strong resistance. 54th Army, attacking from the north, managed an advance of 22km on March 15, but this soon stalled just 10km north of Lyuban.[29]

In early March, Army Group North began preparing a counterstroke to cut off the Soviet Lyuban force in with an effort to relieve its own II Army Corps encircled at Demyansk. While the ground troops were ready by March 9, the counteroffensive was delayed until March 15 due to the Luftwaffe's commitments elsewhere. When it began at 0730 hours two shock groups totalling five divisions with strong air support attacked from Spasskaya Polist and Zemtitsy toward Lyubino Pole at the base of 2nd Shock's penetration. On the first day the northern shock group gained 3km and the southern group gained 1,000m. After two days of crawling through boggy terrain against heavy resistance the northern group cut one supply route on March 18 and the southern group severed the second the next day. The two groups linked up on March 20, trapping 2nd Shock in the half-frozen wastes south of Lyuban.[30]

Even as the counterstroke was underway, Meretskov frantically formulated plans to thwart it. Despite these exertions, by March 26 German forces had formed outer and inner encirclement lines along the Glushitsa and Polist Rivers. He ordered Klykov to form an operational group to spearhead a breakout to the lines of 52nd Army. This assault by the two Armies, which employed all of his reserves, began early on March 27, and by the end of the day the desperate and costly attacks managed to carve out a narrow gap 3-5km wide through the German cordon near Miasnoi Bor. With this small victory Meretskov ordered 2nd Shock to begin a new effort to reach Lyuban on April 2. A further attack on April 8 widened the gap to 6km, but in the meantime the drive on Lyuban had failed again.[31]

By this time the spring rasputitsa had set in, what roads existed became impassable for vehicles, the supply routes through the gap were underwater, and 2nd Shock was running short of ammunition, fuel and food. Command, control and communications within the Army had become impossible. Under these circumstances there was no option but to dig in and await more favorable conditions to resume operations. On April 21 the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts were regrouped, and Meretskov departed for the front west of Moscow. The previous day he had sent his deputy, General Vlasov, into the pocket to replace the ailing Klykov. His mission was to either reinvigorate the offensive or extricate the Army from its perilous position.[32]

By May it was clear to the STAVKA that the latter was the only viable option. Vlasov was ordered to take up an all-round defense, with 13th Cavalry in reserve. The Front commander, Lt. Gen. M. S. Khozin, sent a proposal to the STAVKA that included:

a. Having completed liquidating the enemy in the forests southwest of Spasskaia Polist', the 59th Army will quickly conduct an operation to liquidate the enemy in the Tregubovo, Spasskaia Polist', and Priiutino regions. The 2nd and 377th Rifle Divisions and 29th Tank Brigade will attack from the east, and the 191st, 259th, 267th and 24th Guards Rifle Divisions [will attack] from the west. This operation will tentatively begin on 6 May.

This would focus on the long, narrow salient held by Group Wendel north of the gap, which was the location of the 191st. In further orders the division was subordinated to 59th Army.[33]

In the event, this tentative date was not met, and on May 12 Khozin notified the STAVKA that Group Wendel was being reinforced, which he took as firm evidence that another attempt to cut the corridor was in the offing. In response, at 2050 hours he ordered Vlasov, and the relevant parts of 59th Army, to begin planning their breakout. His plan, after modifications, was approved in the afternoon of May 16. Heavy, chaotic, but mostly futile combat raged for several days as the ragged remnants of 2nd Shock Army, in large and small groups, tried desperately to reach Volkhov Front's lines. The main body of 59th Army could offer little assistance, primarily because its formations were woefully under strength and lacked both tanks and reserves.[34] On May 15, Colonel Korkin was relieved of his command, although he would later lead the 24th Rifle Brigade. He was replaced the following day by Lt. Col. Nikolai Ivanovich Artemenko, who had previously served in the 19th Guards Rifle Division. By June 1, the remnants of the division had escaped the pocket, and were sent to the rear for rebuilding.

Second Sinyavino Offensive[edit]

On August 10 the 191st returned to 2nd Shock Army, still in Volkhov Front. It had just two divisions (the other being the 374th Rifle) on September 1,[35] and the Army was again under command of General Klykov. The STAVKA was anticipating a German summer offensive near Leningrad (which was in fact being planned) and intended to forestall it with an offensive of its own. This attack would break the siege by penetrating the land corridor east of the city between the Neva and Naziia rivers, south of Sinyavino. The "bottleneck" was heavily defended and fortified, and much of the terrain was the usual peat bogs. The 8th Army would provide the offensive shock group from the east, attempting to link up with Leningrad Front's 55th Army.[36]

When the 8th Army's attack started at 0210 hours on August 27 it had roughly a four-to-one force advantage on its 15km-wide penetration sector, and quickly forced a break across the Chernaya River at the boundary between the 227th and 223rd Infantry Divisions. Early the next day the 19th Guards exploited the breakthrough, advancing 5-6km and reaching the southeastern approaches to Sinyavino by nightfall. This promising start was soon stymied as German reserves, including elements of 96th and 170th Infantry Divisions assembled at Sinyavino. On August 29 the Tiger tank made its inauspicious combat debut when four were committed south of Sinyavino Heights; two of them broke down almost immediately and a third had its engine overheat. By the 31st, fierce and skillful German resistance had contained the penetration.[37]

A frustrated Meretskov attempted to get his offensive moving again. On September 5 he committed the 191st from reserve, along with the 122nd Tank Brigade, to replace the worn-out 19th and 24th Guards. However, the fresh forces came under heavy German air and artillery attacks as they deployed forward,[38] and Lt. Colonel Artemenko was killed by shell fragments. His replacement, Lt. Col. Miron Ivanovich Perevoznikov, was not named until September 15, but this officer was removed on September 22 due to illness, and he was succeeded the following day by Lt. Col. Viktor Nikitovich Gretsov, who had previously served as the division's chief of artillery.

The 191st managed to reach the swamps southeast of Sinyavino by September 7, but the losses it had suffered in running the gauntlet had sapped it of the strength necessary to mount a credible assault on the German strongpoint. As well, the German XXVI Army Corps had begun launching counterattacks to regain lost territory. The commander of German 11th Army, Field Marshall E. von Manstein, under orders from Hitler to clear up the situation, concentrated his 24th and 170th Infantry Divisions and 12th Panzer Division to attack the Soviet penetration on September 10, but this attack collapsed almost immediately due to heavy artillery and mortar fire and extensive minefields. Cancelling his planned attacks for the next day, Manstein ordered 11th Army to neutralize the Soviet artillery and prepare another attack from north and south. In a critique from the General Staff on September 15, Meretskov was upbraided for allowing the 191st to be committed to battle with just a handful of mortar shells and 45mm antitank rounds available.[39]

The renewed counteroffensive began on September 21 at the base of the penetration near Gaitolovo and despite desperate Soviet resistance linked up on September 25, encircling the bulk of 8th and 2nd Shock Armies. Belatedly, on September 29 the STAVKA sent Meretskov an order to withdraw his forces from the pocket. During the days following the remnants of the two armies escaped, although fighting persisted until October 15 as the German forces restored their previous front. Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts had suffered 113,674 losses, with most of those falling on the latter, but the German forces had lost an unprecedented 26,000 casualties.[40] The 191st was withdrawn to the Volkhov Front reserves for rebuilding.[41]

Operation Iskra[edit]

During October the 191st returned to 59th Army.[42] On November 2, Colonel Gretsov returned to his position of chief of artillery with the arrival of a new commander, Col. Pavel Andreevich Potapov, who had previously led the 267th Rifle Division. By the start of the new year the division was back in 2nd Shock.[43]

The planning for a new effort to break the German blockade, dubbed Operation Iskra ("Spark") began shortly after the previous offensive had failed. The timing of the offensive would depend on a hard freeze of the Neva, as the forces of Army Gen. L. A. Govorov's Leningrad Front lacked river-crossing equipment, especially for artillery and heavy tanks. He urged that both Fronts attack simultaneously, and the STAVKA approved his plan with only minor amendments on December 2. 2nd Shock would form the assault group for Volkhov Front, while 67th Army would do the same for Leningrad Front. Meretskov's Front was substantially reinforced with five rifle divisions, three ski brigades and four aerosan battalions. While both Fronts were prepared by January 1, on December 27 poor ice conditions on the Neva forced Govorov to request a delay; the offensive was postponed until January 10-12, 1943. 2nd Shock was to smash the German defenses on a 12km-wide sector from Lipka to Gaitolovo, destroy the German forces in the eastern part of the salient in cooperation with 8th Army, and link up with 67th Army. For this task it had 11 rifle divisions, several brigades (including four of tanks), and a total of 37 artillery and mortar regiments.[44]

The offensive began on January 12 with a 140-minute artillery preparation on the 2nd Shock Army's front. All regimental and divisional artillery was mounted on skis or sleighs to improve mobility. The 191st was in the Army's second echelon, attacking in the center with the 256th Rifle Division and 372nd Rifle Divisions, but without any armor support due to the broken, forested and swampy terrain they faced. They went in at 1115 hours along the sector from Lipka to Gaitolovo with two more divisions on their left. Against heavy resistance the assaulting infantry penetrated the forward edge of the 227th Infantry Division's defenses and advanced 2km north and south of Workers Settlement No. 8. Despite heavy fire from that place and Kruglaya Grove, one regiment of the 256th managed to wedge between the two strongpoints but could advance no farther through the murderous fire.[45]

With the advance reduced to a snail's pace the 191st was committed south of Kruglaya Grove on January 14. With the help of this and other piecemeal commitments, the 256th managed to take Podgornyi Station on the same date, and the next day the 372nd captured Workers Settlement No. 8. By late on January 17 the German front was fragmented and the two Fronts were only 1.5-2km apart. At 0930 hours on January 18 lead elements of 67th Army's 123rd Rifle Division and the 372nd joined hands just east of Workers Settlement No. 1.[46] Meanwhile, the 191st cut the road from Sinyavino to Gontovaya Lipka and drove German forces off to the southwest. On January 20, Colonel Potapov handed his command over to Col. Ivan Nikolaevich Burakovskii. Potapov would soon take over the 128th Rifle Division. Burakovskii had previously led the 73rd Naval Infantry Brigade, and he would be promoted to the rank of major general on October 16.

At this point the joint force was ordered by an impatient Marshal Zhukov to wheel southward to capture Sinyavino and the Gorodok settlements. But by now the victorious forces were exhausted, having suffered 115,082 casualties, and Sinyavino and its heights remained in German hands. While land communications with Leningrad had been restored, German artillery would continue to threaten these for another year. The offensive was halted on January 31.[47]

Leningrad–Novgorod Offensive[edit]

The 191st spent the rest of 1943 mainly on the defensive. In February it rejoined 59th Army, which by the start of April consisted of the 191st, 2nd, 377th Rifle Divisions and the 2nd Fortified Region. In August, it joined the 65th Rifle Division to form the 14th Rifle Corps.[48] It remained under these commands into the new year, at which the Corps contained the 191st, 225th and 378th Rifle Divisions.[49]

Novgorod–Luga Offensive[edit]

The final offensive on Novgorod began on January 14, 1944. It opened with an artillery preparation that unleashed 133,000 shells on the German defenses, and assault detachments from each first echelon rifle battalion in 59th Army began the ground attack at 1050 hours. 14th Corps was closest to the objective, with the 191st deployed in the center of the line. Despite the artillery preparation, the assault by 6th Rifle Corps, north of 14th Corps, stalled after advancing only 1,000m. Fortunately for 6th Corps, a regiment of the 378th attacked prematurely and without orders, taking advantage of the fact that German troops had abandoned their forward works during the artillery preparation, and seized a portion of those defenses. The 1254th Rifle Regiment then joined the attack and the two regiments overcame the first two German trench lines and gained a small bridgehead over the Pitba River at Malovodskoe.[50]

By late on January 16 the 14th Corps had cut the Finev Lug–Novgorod road and 59th Army had torn a 20km-wide hole in the German main defensive belt. The following day, despite bad weather, difficult terrain and lack of transport, 59th Army was clearly threatening to encircle XXXVIII Army Corps at Novgorod. On the night of January 19 these forces got the order to break out along the last remaining route. The city was liberated on the morning of the 20th, and on the next day most of the survivors of the German corps were surrounded and soon destroyed.[51] In recognition of this feat, the division was honored as follows:

NOVGOROD... 191st Rifle Division (Major General Burakovskii, Ivan Nikolaevich)... The troops who participated in the battles with the enemy, and the breakthrough and liberation of Novgorod, by the order of the Supreme High Command of 20 January 1944, and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 20 artillery salvos from 224 guns.[52]

In seven days of combat the 59th Army penetrated strong German defenses, liberated Novgorod, and advanced 20km westward, widening its penetration to 50km. While doing so it destroyed or seriously damaged two German divisions, one regiment, four separate battalions, and captured 3,000 prisoners.[53]

Advance on Luga[edit]

By the beginning of February the division had been transferred to the 7th Rifle Corps of 8th Army, still in Volkhov Front.[54] The Army now consisted of the 7th and 14th Corps, plus three tank brigades. 59th Army had been ordered to take Luga no later than January 29-30, with the assistance of 8th Army attacking from the south. The 59th soon stalled along the Luga River, and the advance now became dependent on the 8th. 7th Corps and the 5th Partisan Brigade had taken Peredolskaya Station on January 27; thereafter it changed hands three times in heavy fighting as German reserves were committed. Since 6th Corps was lagging far behind, 7th Corps was forced to defend its overextended right flank by weakening its forces at Peredolskaya. The Corps was able to advance several more kilometres westward and cut the Leningrad–Dno railroad, but Luga remained firmly in German hands.[55]

On February 1 a group of two German battalions and 15 tanks struck the 372nd Division, on the right flank of 7th Corps, and drove it back in disorder, thereby exposing the 256th Division's right flank. At the same time the 8th Jäger Division pushed the 191st, which was now back in 14th Corps, operating on the 256th's left flank, off to the north. These efforts were joined by 12th Panzer Division. On the following day the two German divisions linked up southwest of Melkovichi, cutting off all of the 256th and two regiments of the 372nd. The initial Soviet relief attempts failed, and German Groups Karow and Freissner tried to destroy the encircled force from February 6-15. Through this period it relied on air supply, and was finally relieved by 59th Army on the latter date.[56]

Into the Baltic States[edit]

Volkhov Front, now being excess to requirements, was disbanded on February 15, and 14th Corps was transferred to the reserves of Leningrad Front.[57] By the end of February many of the Front's rifle divisions had lost 2,500-3,500 personnel each since the start of the offensive. In a directive issued on February 22 the STAVKA approved a plan by Army Gen. L. A. Govorov, the Front commander, to employ his 2nd Shock, 59th, and, once it arrived in the region, 8th Army to finally smash the German defenses at Narva. The need to regroup and replenish his Front's forces delayed the new offensive into early March. Early on March 1 the 2nd Shock, which soon included 14th Corps, and 59th struck but made very limited progress over the next two days, after which German forces launched heavy counterattacks against the 59th; the fighting raged on this sector until April 8 without any resolution.[58] By the start of April the 191st was operating under direct control of 2nd Shock.[59]

Capture of Narva[edit]

On March 24 Govorov requested permission to halt his offensive for three to four weeks to prepare more thoroughly for a new offensive. In the event, on March 26 German Group Narva mounted a surprise counterstroke to restore its defenses along the Narva. This attack, along with another effort on April 19, were largely futile in terms of ground gained, but did frustrate Soviet efforts to take Narva and advance into Estonia.[60] During April the 191st was assigned to 43rd Rifle Corps, still in 2nd Shock Army, where it remained into June. As of the start of July it was back under direct Army command.[61]

The final attack on Narva began overnight on July 25/26. North of the city the 191st began crossing operations near Vasa. Sergeant Efim Ivanovich Solomennikov was a squad leader of the 5th Company of the 546th Rifle Regiment. In the course of attempting to force the Narva River his boat was disabled by German fire and his companions were all killed or wounded. He then swam to the west bank despite a minor wound, and was the first to enter a German trench where he killed two officers in hand-to-hand combat while capturing two more. Solomennikov then led a small group in repelling counterattacks until the rest of the Company could get over. As the fighting expanded, his platoon commander disappeared, and he took effective command, and personally subdued a machine gun bunker; his platoon would account for 30 German soldiers and three guns. Although again wounded, Solomennikov did not leave the battlefield until ordered by his battalion commander. After his release from hospital he went on to serve as commander of a scout squad in the 142nd Rifle Division. On March 24, 1945, he was made a Hero of the Soviet Union. After demobilization he returned to Buryatia, where he had lived before the war, and worked in forestry until his retirement. He died on January 23, 1986, at the age of 87.[62]

Narva finally fell on July 26, and the 559th Rifle Regiment (Lt. Colonel Bashilov, Aleksandr Konstantinovich) was given its name as a battle honor.[63] By the beginning of August the division had been reassigned to the 112th Rifle Corps of 8th Army, still in Leningrad Front.[64] During the month it advanced south along the east shore of Lake Peipus. On August 26, General Burakovskii left the division to further his military education; he would hold several commands postwar. He was replaced the next day by Col. Aleksei Yakovlevich Tsygankov, who had previously led the 177th Rifle Division.

Advance on Riga[edit]

Also during August, the 191st was moved to the reserves of 3rd Baltic Front.[65] By the second week of September it had advanced as far as Võru, Estonia.[66] On September 26, Colonel Tsygankov was replaced by Maj. Gen. Grigorii Osipovich Lyaskin. This officer had held several other divisional commands, most recently the 337th Rifle Division. At about this time the division had been assigned to the 111th Rifle Corps in 67th Army, still in 3rd Baltic Front.[67] By the first week of October it had reached the Gulf of Riga near Salacgrīva.[68]

Shortly after Riga was taken on October 13 the 3rd Baltic Front was disbanded, and the 191st was again transferred, now to the 84th Rifle Corps of 4th Shock Army in 1st Baltic Front.[69] By this time the continuous offensive fighting in the Baltic States had taken its toll. Although the 191st was classified as an "assault" division, each of its rifle regiments was down to two rifle battalions with a combat strength of just 300-400 men per battalion. In December, as preparations for the invasion of Poland and Germany began, the division was shifted south to 2nd Belorussian Front for rebuilding. It would remain in this Front for the duration of the war.[70]

Into Poland and Germany[edit]

At the start of the new year the 191st was in 50th Army as part of the 69th Rifle Corps, which also contained the 110th, 153rd and 324th Rifle Divisions.[71] At the start of the winter offensive the 50th Army was deployed on the right flank of its Front, and had a defensive role in the first days, deployed on a line from Augustów to Osowiec to outside Nowogród. It was not ordered to advance until January 17, and it encountered heavy resistance from German rearguards, slowing its progress. The Army occupied the strongpoints of Arys and Johannisburg, and on January 26 was fighting along a line 8km southeast of Rhein, Ruciane-Nida, Mikołajki and Kerwin Station.[72] By the end of the month the 191st had been detached from 69th Corps and was under direct Army command.[73]

By February 8, elements of the Army had captured Heilsberg and penetrated the German permanent fortifications of East Prussia. The next day 50th Army was ordered to be transferred to 3rd Belorussian Front,[74] but the 191st was instead moved to 49th Army, where it would remain for the duration.[75] This Army was to be inserted into the front line between 65th and 70th Armies on the same morning. The Front commander, Marshal K. K. Rokossovskii, was preparing to lead his forces across the Vistula River and into Pomerania.[76] The division would soon be assigned to 70th Rifle Corps.[77]

As of February 10, most of 49th Army was deployed along the line Kulm–Grodek–Sierosław–Lniano in preparation for the offensive into eastern Pomerania. On February 19 the Army was ordered to continue its attack in the direction of Sominy and Bytów, with the task of capturing the line Sominy–Kloden–the Liaskasee by the end of February 24. This advance brought the Army's forces to the approaches to Gdańsk, and during the fourth stage of the offensive, from March 14 to 30, the 49th was one of the armies that cleared and occupied the city.[78] In the course of this advance the 546th Rifle Regiment took part in the fighting for Czersk, and on April 5 it would be awarded the Order of the Red Banner.[79] On April 26 the 552nd Regiment would receive the same honor for its role in taking Bytów and Kościerzyna.[80]

Berlin Operation[edit]

On March 20 General Lyaskin had left the division to take up a staff position in the 18th Rifle Corps. He was replaced by Col. Georgii Andreevich Shepel, who would remain in command until the division was disbanded. As of April 1 it was again operating under direct Army control.[81]

At the start of the Berlin Strategic Offensive the rifle divisions of 2nd Belorussian Front varied in strength from 3,600 to 4,800 personnel each. 49th Army deployed on a 16km front on the Oder River from Kranzfelde to Nipperwiese. The 191st was one of three divisions (not organized as a Corps) that formed the Army's second echelon. During April 18/19 the Front launched intensive reconnaissance efforts in preparation for the crossings, including the elimination of German advance parties in the lowlands between the East and West Oder. The next day the operation continued, hindered by heavy German fire. In the Army's zone three ferry crossings, a 50-ton and a 16-ton bridge were in operation. On April 24 the 191st got one rifle battalion across. The next day the 49th Army exploited the greater success of the 65th and 70th Armies in their crossing operations and passed its remaining forces to the west bank along the Harz sector using the 70th Army's ferries. Attacking to the southwest and having beaten off five German counterattacks the Army advanced 5–6km in the day's fighting, and by the evening the 121st Corps had reached the line Pinnow–Hohenfelde.[82] It was at about this time that the 191st was assigned to this Corps.[83] Throughout April 29–30, 49th Army attacked to the west, beginning in the Neustrelitz area, and on May 3 its forward detachments established contact with British Second Army advance units in the Grabow area.[84]

Postwar[edit]

The men and women of the division ended the war with the full title of 191st Rifle, Novgorod, Order of the Red Banner Division. (Russian: 191-я стрелковая Новгородская Краснознамённая дивизия.) Further honors were received by several subunits on June 4. The 552nd Rifle Regiment was awarded the Order of Suvorov, 3rd Degree, for its part in the capture of Eggesin, Torgelow, and other German towns.[85] The 559th Regiment received the same award for the taking of Stettin, Penkun, Casekow, and other places.[86] In addition, for their parts in the fighting for Anklam, Friedland, and other places, the 8th Antitank Battalion was given the Order of Alexander Nevsky, and the 330th Sapper Battalion won the Order of the Red Star.[87]

According to STAVKA Order No. 11095 of May 29, 1945, part 6, the 191st is listed as one of the rifle divisions to be "disbanded in place".[88] The division was disbanded in July.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Charles C. Sharp, "Red Legions", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed Before June 1941, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. VIII, Nafziger, 1996, p. 92. This source misnumbers the 552nd Rifle and 484th Artillery Regiments.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 7

- ^ Sharp, "Red Legions", p. 93

- ^ David M. Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2002, pp. 18-20

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 37-39

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 22

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 39, 41-42

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 46-47, 51, 53, 60-61

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, p. 61

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 70-73, 75, 77-78

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 78-80

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 92-94

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 65

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 94-96

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 96-97

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 97-100

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 100-01

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 104-05

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 106-09

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 104.

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 109-111

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, p. 112

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 25

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 165-66

- ^ Aleksander A. Maslov, Fallen Soviet Generals, ed. & trans. D. M. Glantz, Frank Cass Publishers, London, UK, 1998, pp. 39, 211

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 158, 162-63, 165

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, p. 167

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, p. 168

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 168-70, 172

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 174-76

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 176-81

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 182-83

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 191-94

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 196-97

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 164

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 213-17

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 218-21

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, p. 222

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 222-23, 229

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 224, 226-28

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 188

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 209

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 9

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 264-67

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 269-70, 275, 278-79

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 281-82

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 284-85

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 58, 81, 214

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 10

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 345-46

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 347-49

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-4.html. In Russian. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, p. 349

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 36

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 362-63

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 385-87

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 66

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 396, 401-03

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 96

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 404-05

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 126, 157, 186

- ^ https://warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=12720. In Russian, English translation available. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ https://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-4.html. In Russian. Retrieved December 12, 2023

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 215

- ^ Sharp, "Red Legions", p. 93

- ^ The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, Multi-Man Publishing, Inc., Millersville, MD, 2009, p. 29

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 279

- ^ The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, p. 36

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 310

- ^ Sharp, "Red Legions", p. 93

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 13

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, pp. 131, 201, 213-14

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 47

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 236, 238

- ^ Sharp, "Red Legions", p. 93

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, p. 238

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 82

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 295, 303, 312, 328-32

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 83.

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 170.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 118

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation, 1945, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., chs. 11, 14, 18

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 153

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation, 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 21

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 377.

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 371.

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 379.

- ^ STAVKA Order No. 11095

Bibliography[edit]

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. p. 92

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. p. 198