1834 massacre of friars in Madrid

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

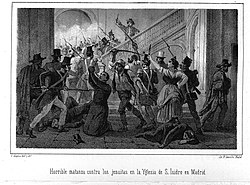

The massacre of friars in Madrid in 1834 was an anti-clerical riot that took place on July 17, 1834, in the capital of Spain during the regency of Maria Cristina and the first Carlist war (1833-1840) in which several convents in the center of Madrid were assaulted and 73 friars were killed and 11 were wounded, because of the rumor that spread through the city that the cholera epidemic that had been ravaging the city since the end of June and that had worsened on July 15 had occurred because "the water in the public fountains had been poisoned by the friars".[1] "The result of little more than twelve hours of violence" was a "party of blood and vengeance".[2] "It was the first time that the Church had been subjected to the uncontrolled actions of its own believers. As contemporaries observed, these events demonstrated, above all, the loss of prestige of the religious in Catholic Spain, as was happening in other countries".[3]

Background[edit]

In April 1834 the regent María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias promulgated the Royal Statute, a kind of granted charter by which she intended to gain the support of the liberals for the cause of her daughter, the future Isabella II, who was then four years old, and whose inheritance rights had not been recognized by the Carlists, the supporters of the brother of the recently deceased King Ferdinand VII, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, who did not accept the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830 that abolished the Salic Law that did not allow women to reign, so he lost his rights to the throne in favor of his brother's daughter. After the death of Ferdinand VII, at the end of September 1833, the succession dispute led to a civil war, the first Carlist war, which soon became a political and ideological conflict, between those in favor of maintaining the Old Regime, the absolutists who mostly supported Don Carlos -the "Carlists"-, and the defenders of a more or less radical change towards a "new regime", who defended the rights to the throne of Isabella II, for which they were called "Isabelinos" or "cristinos", after the name of the regent. Among the supporters of the "Carlists" were most of the members of the religious orders who, besides sharing the absolutist ideas of the Carlists synthesized in their trilemma "God, Motherland, King", also feared that the coming to power of the liberals would put an end to their existence. As Julio Caro Baroja pointed out in his pioneering study on anti-clericalism in Spain: "The cheers for Don Carlos went hand in hand with cheers for the Inquisition, and the rallies of villagers instructed by churchmen were everywhere, especially in Catalonia, the main theater of operations for the rebellions of 1827".[4]

Events[edit]

Cholera epidemic and "poisoning of the springs"[edit]

Between 1830 and 1835 a cholera epidemic, which had originated in India around 1817, spread throughout Europe. It reached Spain in January 1833, the first town affected being Vigo, where it had probably been brought by English ships. At the end of 1833 it had spread through Andalusia and from this point or from Portugal it had been brought to Castile by the troops of General José Ramón Rodil y Gayoso who had gone to fight the Portuguese Miguelistas and the Carlists. At the same time it was spread by the ports of the Mediterranean by a military ship coming from France. During the two years that the epidemic lasted, it caused more than one hundred thousand deaths throughout Spain and half a million people fell ill.[5] Rodil's army, coming from the border of Portugal, followed the path of the cholera epidemic that had isolated Andalusia and that had forced the establishment of sanitary fences in La Mancha, but it was not prevented from entering Madrid, from where it was heading north to relieve the troops of General Vicente Genaro de Quesada, who were unable to control the Carlist rebels.[6]

In Madrid the first cases of cholera occurred at the end of June 1834 and although the government of Francisco Martínez de la Rosa denied its existence, he quickly left Madrid on June 28, together with the regent María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias and the royal family, to take refuge in the palace of La Granja in Segovia, which caused great indignation among the inhabitants of the capital.[7] To this feeling of helplessness was added the summer heat, rising food prices and rumors of imminent Carlist attacks, which increased popular discontent.[1] On July 15, news reached Madrid that Rodil's army had not been able to contain the Carlists either and that the pretender Carlos María Isidro de Borbón had entered Spain, proclaiming it in a manifesto from Elizondo.[6]

On the very day that the bad news about the progress of the first Carlist war reached Madrid, the epidemic broke out again, "the sick died by the hundreds, with the horrifying circumstances that accompany such a cruel plague", according to Alcalá Galiano's account.[8] The main victims were the inhabitants of the poorest neighborhoods where more than five hundred people had died every day since the 15th. Throughout the month of July, the victims of this epidemic numbered 3,564 people, dropping to 834 in August.[7]

At that time, a rumor began to circulate in Madrid that the cause of the epidemic was the poisoning of public fountains, since "cholera manifested itself in many people after drinking water," according to a witness. The idea that water poisoning was responsible for the disease was also spread in other parts of the world among the urban working classes, who were convinced that the upper classes were behind it and wanted to reduce the number of indigents. In Manila, in 1827, the supposed poisoning was attributed to English subjects and some were murdered; in Paris, in March 1831, the friars and the legitimists were blamed and some of them were persecuted, and in 1833 the tavernkeepers were blamed with the complicity of the police, and several agents were thrown into the Seine. In Madrid, according to an eyewitness, it was first blamed on "some semi-beggar boys and some whores who approached the fountains, and from this concept came the imprisonment of some women cigar sellers, the murder that was committed in the person of a young man of the lowest class at 3 in the afternoon of the 17th in the Puerta del Sol, and the persecution of other boys in the fountains of Lavapiés, Relatores and others". But soon the rumor spread that those "semi-beggars" and those "whores" were in the service of the friars who were the real culprits. The news also spread that shots had been fired from the convents against the masses that were heading towards them, relating it to the support that the religious were giving to the Carlists.[9]

The rumor that "the water of the public fountains had been poisoned by the friars", especially by the Jesuits, was reinforced by the fact that some of them in the previous days had explained the cholera epidemic as "divine punishment against the unbelieving inhabitants of the city, while the people of the countryside remained free because they were faithful and devout".[7]

Assault on the convents[edit]

Everything took place in the most central area of Madrid, between Puerta del Sol, Plaza de la Cebada, the convent of San Francisco el Grande and the streets of Atocha and Toledo. The first violent event took place at 12 noon in the Puerta del Sol with the murder of a boy who had thrown dirt into a water carrier's bucket. According to Benito Pérez Galdós in Un faccioso más y algunos frailes menos (chap. xxvii), it was a frequent prank, which was "commonly punished with a slap in the face", but on that occasion it was taken as an excuse to blame the friars, when the news spread through the corridors, proclaimed by spontaneous speakers, that "of the two boys who had been surprised [. ...] throwing some yellow earth into the water carriers' vats, one was killed instantly; the other managed to escape and took refuge.... Where? In San Isidro itself". In a similar way, Benjamín Jarnés narrates the triggering of the tragedy:

Cholera appears in Madrid [...] A little boy plays in the Puerta del Sol, next to the Mariblanca fountain. Suddenly an idea came to him to throw a handful of earth into a water carrier's bucket. The water carrier goes after the boy, and behind them a few idle people swarm nearby. The crowd swells. One of them shouts:

—That one, the friars sent him to poison the water!

They caught up with the miserable boy, stabbed him to death and dragged his corpse down Main Street.

The tumult intensifies. The mobs spread out in groups, spread out through the convents. At noon a crowd of women dragged a layman. At three o'clock in the afternoon the mobs entered the Jesuit convent of San Isidro; they killed, plundered, burned...

Benjamín Jarnés, Sor Patrocinio. La monja de las llagas, IV.

After the events of the Puerta del Sol, the second violent event occurs an hour later in the Plaza de la Cebada where a well-known royalist is attacked and killed. At four o'clock in the afternoon a Franciscan religious is attacked in Calle de Toledo.[2]

In the early afternoon, various groups had already formed, also made up of many urban militiamen and some members of the royal guard, who had gathered in the Plaza Mayor, in the Puerta del Sol and in the Plaza de la Cebada, shouting protests against the friars.[10] From there these groups went to the Imperial College of San Isidro run by the Jesuits, which was assaulted at five o'clock in the afternoon. "The pretext, to corroborate the version that since the previous day had spread about two women cigarette sellers from the nearby tobacco factory, they said they were surprised with poison powder to pour into the fountains and that they were paid by the Jesuits. Inside the convent they kill some with sword blows, seize others and lynch them in the side streets, stripping and riddling the dying bodies with mockery. The troops arrive after half an hour with none other than the captain general and police superintendent, Martínez de San Martín, an expert in repressing riots of the exalted liberals during the constitutional triennium in Madrid. He reproaches the Jesuits for the poisoning and looks for proof of it, while they continue killing friars in his presence".[2] A total of fourteen Jesuits were killed.[11]

The next target of the mutineers was the convent of Santo Tomás of the Dominicans on Atocha Street where part of the friars had already had time to flee. There, in addition to killing seven friars in the presence of the troops, who did nothing to prevent it, the mutineers carried out burlesque acts by dressing up in liturgical clothes and forming a sacrilegious dance that continued along the streets of Atocha and Carretas. Around nine o'clock at night the convent of San Francisco el Grande was assaulted, where forty-three Franciscan friars were murdered (or fifty, according to other sources) in the midst of macabre scenes, while the officers of the regiment of the Princess, billeted on the premises, failed to give any order to intervene to the more than one thousand soldiers who composed it. At eleven o'clock at night the convent of San José of the Mercedarios in the present Tirso de Molina square was attacked, with the result of nine or ten more murders.[11][12]

After midnight there were scattered attempts of assaults on other convents, but there were no more victims. "However, the rest of the friars were left in terror: some opted to disguise themselves and take refuge in the houses of friends; the Capuchins of the Prado opted for the heroic act of opening the doors and waiting in prayer".[12]

Julio Caro Baroja affirmed that "no less than seventy-five were the religious murdered in Madrid on July 17, 1834. In San Francisco el Grande, seventeen fathers, four students, ten laymen and ten donates; that is, forty-one Franciscans. In the Imperial College of San Isidro, seventeen Jesuits died: five priests, nine teachers and three brothers. In the convent of Santo Tomás, six Dominicans (five mass priests and one layman). Finally, in the convent of La Merced, there were seven known discalced Mercedarians and four others whose names were unknown at the time".[13]

Government response[edit]

In the early morning of the following day, July 18, the state of siege was declared and a proclamation was made public: "Madrileños: the authorities are watching over you, and whoever conspires against you, against health or public peace, will be handed over to the courts and will be punished by the laws". In the afternoon of that same day there were new attempts of assaults to convents that were avoided by the presence of the troops, although several dependencies of the Jesuits and the convent of the Trinitarians were looted.[11]

On July 19, the government of Francisco Martínez de la Rosa, in view of the ambiguity and the notorious passivity and even connivance with the mutiny of the different authorities -military and municipal-, arrested and imprisoned Captain General Martínez de San Martín, who had a troop of nine thousand men to have prevented the assaults and murders, and forced the corregidor, the Marquis of Falces, and the civil governor, the Duke of Gor, to resign, as the most responsible of the urban militia, many of whose members had had a very active participation in the events.[14] The new civil governor, Count Vallehermoso, suspended the enlistment of new battalions and months later forty militiamen were expelled as a result of their attitude in the events of July.[15] "The commanders of the militia were forced by the discredit of this institution to address an exposition to the queen in order to save its good name, in which they asked for its reform to avoid the entry of undesirable persons into the corps".[16]

Seventy-nine persons (54 civilians, 14 urban militiamen and 11 soldiers) were put on trial. Two people were condemned to death - a cabinetmaker and a military musician - but for the crime of robbery, not for murder, being executed on August 5 and 18. The rest were condemned to various sentences, of galeras and imprisonment, including women, and some were acquitted.[14][17] From the data collected in the trials, it is known that most of those who participated in the riot belonged to the most popular neighborhoods of Madrid and among them there were artisans, employees and women, together with urban militiamen and soldiers.[18]

On July 23, the eve of the opening of the Cortes del Estatuto Real, the police dismantled an alleged plot to overthrow the government of Martínez de la Rosa and to convene a genuinely liberal Cortes, which was headed by "emigrants returned from exile and notabilities of the situation", according to the police report. José de Palafox, Juan Romero Alpuente, Lorenzo Calvo de Rozas, Juan de Olavarría and Eugenio de Aviraneta, among others, were arrested.[19] This conspiracy was known as La Isabelina after the name of the secret society that was supposedly behind it, called "Confederación de guardadores de la inocencia o isabelinos". The detainees were tried but were acquitted for lack of evidence so that the government "had to release them and was ridiculed".[20]

Interpretation of the events[edit]

Historians are divided as to the explanation of the events, for while some defend that the assaults on the convents and the murders of the friars were the result of a plot organized by secret societies or by Freemasonry, others defend the spontaneity of the movement.[11] The defenders of the first thesis, such as Stanley G. Payne, affirm that the rumor about the poisoned wells that triggered the anticlerical mutiny would have been spread by radical secret societies -although not necessarily Freemasonry-.[17] For Manuel Revuelta Gonzalez, another defender of the conspiracy thesis, the way the riot developed proves that it was not a spontaneous coincidence but that behind it there was an organizing head, the secret societies, which counted on the support of the urban militia, thugs and harlots for the execution of the riot.[21]

Against them, other historians such as Josep Fontana or Ana Maria Garcia Rovira, have denied that there was a plot of Masonic boards or secret societies, among other reasons, because there is no evidence to prove it. Josep Fontana says: "there is no evidence that there was any kind of conspiracy behind these events, as there was none behind the many similar events that took place from Manila to Puebla de los Angeles, passing through Paris".[22] According to Josep Fontana, "to be able to understand what happened it is necessary to examine the very core of an anti-clericalism -directed almost exclusively against the religious orders- that was being accentuated in these years, by verifying the identification of the regulars with Carlism, their complicity in the arming of parties and even the direct participation of friars in assaults and ambushes in which, let us not forget this detail, the men who died on the side of the liberals came exclusively from the popular classes: they were sons or brothers of these same people throughout Spain. As Lamennais would say in 1835: "Wherever the priest allies himself with despotism against the people, what destiny awaits him?".[23] A proof of this anticlericalism would be the numerous romances that spread days later that tended to blame everything on the friars:[24]

(...) and as if by leaps and bounds

(let it be said bluntly)

within Madrid itself

the cholera was spreading,

they did not hesitate to spread

that it was punishment from heaven

or divine wrath

that threatened the soil,

because already religion and faith

are being lost

the entrance of friars into the convents

of friars in the convents,

the canonries suspended,

and the holy office suspended,

with a thousand other suspensions

that will come in due time...

The vulgar, always indiscreet,

always unjust, always atrocious,

and always blind instrument

of cowardly murderers

made a bloody theater

of vengeance,

the asylum of the defenseless innocent.

Julio Caro Baroja in his pioneer work on anti-clericalism in Spain, published in 1980, attributed the origin of the massacre to the transformation in the collective mentalities of certain popular sectors:[25]

In the process of creating a liberal mythology, with its gods, demi-gods and evil genii, many rushed to interpret all the activities of the Church in a hostile way, at some point a large part of the people attributed to the Church and its ministers the same kind of slogans and evil acts that preachers, friars, etc., had attributed in another era to heretics and Jews, and more modernly to Masons and members of the various secret societies. The people, then, carried out a typical "projection", attributing to the political enemies not only true intentions, but others imagined, fantastic and adjusted to a procedure that is known to us, for the repeated in different circumstances, throughout History.

An in-between position is held by Juan Sisinio Perez Garzon who affirms "that it is not incompatible the existence of an organizational plot to destroy the ecclesiastical power and to overthrow the government, with the fact that this one overlaps and takes advantage of a situation of popular exasperation - by the cholera - to sow terror among the friars and to use a tactic of panic to justify the assault to the clerical possessions".[26] According to this historian, the way in which the liberal newspaper El Eco del Comercio reported the news of the riot would constitute an indication of who could have been behind the events when it transformed the victims into "enemies of the Motherland", the lynching of the religious was reduced to the concept of "some misfortunes" and affirmed that in the assaults "it is said that some evidence was discovered that gave foundation to the voices that have run in the previous days about their plan for the poisoning of the waters. Everything can be believed of the perversity of the enemies of the Motherland, and we have always foreseen that they would take advantage of the present moments to increase the conflict in which we are..."[27]

A similar position is held by Antonio Moliner Prada when he recognizes "that the radical liberals were interested in accelerating the process of the Revolution and were interested in political destabilization and direct attacks on the Church", but he goes on to point out that the "accumulated secular hatred against the clergy manifested itself in all its crudeness during those days and served as a precedent for the anticlerical riots that were repeated during the summer of 1835 in some cities. As J. de Burgos pointed out, the massacre of the friars provoked terror among the wealthy middle class and the bourgeoisie: (...) "the police were shaken and the wealthy and naturally peaceful classes of the neighborhood of the capital were shocked". The participation of the people in the events of 1835 would make clear to the progressive liberals what they had already sensed in 1834, the need to establish a strategy that would avoid the radicalization of the process of the Revolution and could challenge the new bourgeois order that they were trying to consolidate".[28]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Moliner Prada 1998, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Pérez Garzón 1997, p. 82.

- ^ Moliner Prada 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Caro Baroja 2008, p. 143.

- ^ Fontana 1977, p. 98.

- ^ a b Pérez Garzón 1997, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Fontana 1977, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Fontana 1977, p. 99.

- ^ Fontana 1977, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Moliner Prada 1998, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b c d Moliner Prada 1998, p. 77.

- ^ a b Pérez Garzón 1997, p. 83.

- ^ Caro Baroja 2008, p. 146.

- ^ a b Pérez Garzón 1997, p. 84.

- ^ Pérez Garzón 1997, p. 86.

- ^ Moliner Prada 1998, p. 81.

- ^ a b Moliner Prada 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Pérez Garzón 1997, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Pérez Garzón 1997, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Fontana 1977, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Moliner Prada 1998, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Fontana 1977, p. 10.

- ^ Fontana 1977, p. 102-103"In the Cortes of 1839, Alonso denounced, without anyone contradicting him, the falsity of accusations that had been a mere pretext to justify the repression against some progressives."

- ^ Moliner Prada 1998, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Caro Baroja 2008.

- ^ Pérez Garzón 1997, p. 85.

- ^ Pérez Garzón 1997, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Moliner Prada 1998, pp. 81–82.

Bibliography[edit]

- Caro Baroja, Julio (2008) [1980]. Historia del anticlericalismo español (in Spanish). Madrid: Caro Raggio. ISBN 978-84-7035-188-4.

- Fontana, Josep (1977). La Revolución Liberal. Política y Hacienda 1833-1845 (in Spanish). Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Fiscales. ISBN 84-7196-034-6.

- Moliner Prada, Antonio (1998). "Anticlericalismo y revolución liberal". El anticlericalismo español contemporáneo (in Spanish) (La Parra López, Emilio and Suárez Cortina, Manuel ed.). Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. ISBN 84-7030-532-8.

- Pérez Garzón, Juan Sisinio (1997). "Curas y liberales en la revolución burguesa". El anticlericalismo (in Spanish) (Rafael Cruz ed.). Madrid: Marcial Pons (Journal Ayer, nº 27). ISBN 84-7248-505-6.